Provable Diffusion Posterior Sampling for Bayesian Inversion (2512.08022v1)

Abstract: This paper proposes a novel diffusion-based posterior sampling method within a plug-and-play (PnP) framework. Our approach constructs a probability transport from an easy-to-sample terminal distribution to the target posterior, using a warm-start strategy to initialize the particles. To approximate the posterior score, we develop a Monte Carlo estimator in which particles are generated using Langevin dynamics, avoiding the heuristic approximations commonly used in prior work. The score governing the Langevin dynamics is learned from data, enabling the model to capture rich structural features of the underlying prior distribution. On the theoretical side, we provide non-asymptotic error bounds, showing that the method converges even for complex, multi-modal target posterior distributions. These bounds explicitly quantify the errors arising from posterior score estimation, the warm-start initialization, and the posterior sampling procedure. Our analysis further clarifies how the prior score-matching error and the condition number of the Bayesian inverse problem influence overall performance. Finally, we present numerical experiments demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method across a range of inverse problems.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper is about solving “inverse problems,” which means figuring out hidden things from messy or indirect measurements. Think of trying to recover a clear picture from a blurry, noisy photo, or guessing what’s inside the body from an MRI scan. The authors build a new, reliable way to generate many possible answers (not just one) and to know how uncertain those answers are. They do this with a modern tool called a diffusion model and prove that their method really works, even when there are many different valid answers.

What questions are the authors asking?

- How can we use powerful, data-driven priors (what we believe about images or signals before seeing measurements) to solve inverse problems without retraining for each new task?

- How can we sample from the full posterior (the distribution of all possible answers given the measurement) accurately and efficiently, even when that distribution has multiple “modes” (very different plausible answers)?

- Can we do this with provable guarantees, not just heuristics?

How does the method work? (Explained simply)

First, a few ideas in everyday language:

- Prior: Your educated guess about what things usually look like (for example, natural images).

- Likelihood: How the measurement is produced from the hidden thing (for example, blurring + noise).

- Posterior: All the possible hidden things that fit the measurement, weighted by how likely they are given both the prior and the measurement.

- Diffusion (forward): Add random noise step by step to make things simpler.

- Reverse diffusion: Remove the noise step by step, guided by a “score” (a vector that points toward more likely answers).

- Score: Think of it like the slope that tells you which way probability increases; it helps guide reverse diffusion.

What they do:

- Learn a reusable prior from data

- The model first learns the “prior score” from lots of clean data (no measurements needed). This learned score captures the structure of real images/signals. It’s plug-and-play: once trained, you can use it with many measurement types without retraining.

- Use reverse diffusion to sample the posterior

- To get samples from the posterior (all likely answers given the measurement), the method must run a reverse process that “denoises” step by step.

- This reverse process needs the “posterior score” at each time step. That’s the hard part.

- Estimating the hard part (posterior score) without guesswork

- Previous methods often used shortcuts that can bias the results (e.g., pretending a complicated distribution is a single point or a simple Gaussian).

- The authors avoid these shortcuts. They derive a formula (a conditional version of Tweedie’s formula) that links the posterior score to the average of many “particles” (think: many guesses) sampled from a softened target distribution.

- They sample those particles using Langevin dynamics, which is like a guided random walk: you move randomly, but with a gentle pull toward more likely answers based on the learned prior and the measurement.

In short: They estimate the needed direction (the posterior score) by averaging many smart, guided random guesses—no crude approximations.

- Warm-start to make reverse diffusion stable

- Normally, reverse diffusion starts from pure noise (a big, simple Gaussian). But the authors prove they must start from a smaller amount of noise (a smaller “terminal time”) to keep the math sound and the sampling accurate.

- Because of this, the starting distribution isn’t just a standard Gaussian anymore. So they design a “warm-start”: they use another Langevin sampler to draw starting points directly from the correct (but still easy) noisy distribution. This makes the whole process more reliable.

Analogy: Imagine hiking down from a foggy spot to a hidden valley (the true answers). The “score” tells you which way is downhill. The authors show how to get good downhill directions by sending out many scouts (particles) that explore intelligently, then averaging where they point. They also make sure you start your hike from a reasonable place (warm-start), not from the top of a random mountain.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Here are the main results and their importance:

- They provide provable guarantees (non-asymptotic error bounds)

- They show their method converges to the correct posterior even when the posterior has multiple separate peaks (multi-modal). This is a big deal because many real problems have more than one plausible solution.

- They precisely quantify where errors come from:

- Estimating the posterior score with particles

- The warm-start approximation

- The reverse diffusion sampling itself

- They show how performance depends on:

- How accurate the learned prior score is

- The “condition number” of the problem (roughly, how curved or tricky the landscape is)

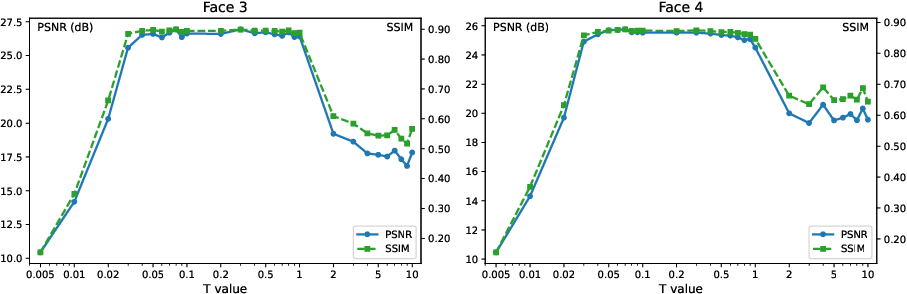

- They give practical guidance: how long to run the particle sampler, and how much noise (terminal time) is safe to use.

- They avoid biased shortcuts used in earlier work

- No “pretend it’s a point” or “pretend it’s a Gaussian” tricks. Their Monte Carlo approach targets the real quantity they need: the gradient of the log-likelihood inside the posterior score.

- They demonstrate strong performance in practice

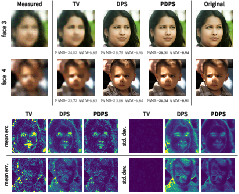

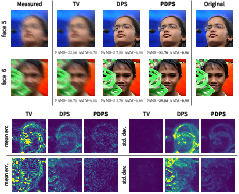

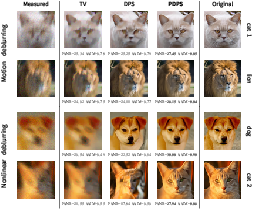

- On challenging image tasks (denoising, deblurring, and nonlinear deblurring on FFHQ faces), their method produces high-quality samples and meaningful uncertainty estimates.

What is the broader impact?

- More trustworthy solutions to inverse problems

- Because the method samples from the full posterior, it naturally represents uncertainty and multiple plausible solutions. This matters in medicine, science, and engineering, where being honest about uncertainty can be critical.

- Plug-and-play across many tasks

- Train the prior score once on data; then mix it with different measurement models at test time. This saves effort and makes the approach flexible.

- Strong theory backing modern generative tools

- The paper helps bridge cutting-edge generative models (diffusion) with rigorous math, making them safer and more reliable for real-world decision-making.

One-line takeaway

The authors build a diffusion-based, plug-and-play sampler that can faithfully explore all plausible answers to an inverse problem—without crude approximations—and they prove it works, even when there are many different correct answers.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of unresolved issues, missing analyses, and open questions that future work could address to strengthen and generalize the proposed framework.

- Discretization error and step-size schedules: The analysis is conducted in continuous time for both the reverse SDE and the inner Langevin dynamics (RGO sampling), but practical implementations use discretized schemes (e.g., Euler–Maruyama/ULA). There is no non-asymptotic control of discretization bias, stability conditions, or guidance on step-size schedules and their cumulative effect on posterior approximation over the full reverse-time trajectory.

- Computational complexity and scalability: Each posterior score evaluation requires running an inner Langevin chain to approximate the posterior denoiser D(t, x, y). The paper does not analyze the computational cost per reverse-time step, how cost scales with dimension, number of particles m, simulation horizon S, or the full trajectory length, nor provide complexity bounds or principled trade-offs for choosing m and S.

- Warm-start practicality and analysis: The warm-start strategy (sampling q_T(·|y) at small T) is proposed because T must be small, but:

- The paper does not fully specify a practical algorithm to sample q_T(·|y) without relying on a Gaussian approximation (especially how to compute ∇log q_T for warm-start).

- No mixing-time or convergence guarantees are provided for the warm-start chain, nor guidance on initialization or diagnostics for whether warm-start samples are sufficiently close to q_T.

- Dependence on semi-log-concavity and unknown curvature parameter α: The guarantees hinge on log-concavity of the RGO density for t < ½ log(1 + α⁻¹), where α lower-bounds the posterior curvature. It is unclear how to estimate α from data, how to select T in practice when α is unknown, and what happens when the semi-log-concavity assumption fails (e.g., heavy-tailed priors, strongly nonconvex likelihoods).

- Sensitivity to prior score estimation error: While the bounds “quantify” the effect of the pre-trained prior score error, there is no robustification strategy when s_prior is biased (e.g., dataset shift, out-of-distribution measurements). It is unknown how mis-specification of the prior score affects mode coverage, uncertainty calibration, and whether MCMC corrections (e.g., MALA/Metropolis steps) could debias the procedure.

- Inner-chain initialization p_t0(·|x, y): The algorithm requires an initial density for the RGO Langevin dynamics at every evaluation point x along the reverse path. There is no guidance on how to choose p_t0, whether chain states can be efficiently reused across nearby x or timesteps, or how poor initialization affects bias and variance of D(t, x, y).

- Variance and noise in score estimates: The posterior score estimator s_mS(t, x, y) introduces Monte Carlo noise whose impact on the stability of the reverse SDE and final posterior accuracy is not quantified. There is no adaptive scheme for m or S (e.g., variance control, confidence intervals, or stopping criteria), nor variance-reduction techniques (control variates, correlated sampling, particle reuse).

- Mode coverage and mixing in multimodal posteriors: Although the method targets multimodal posteriors, the theory does not provide guarantees of mode coverage, diagnostics for poor mixing, or conditions under which the reverse process with noisy scores can traverse low-density regions between modes.

- Requirements on differentiability and known likelihood gradients: The approach assumes a known, differentiable likelihood (∇ℓ_y). Many inverse problems involve nondifferentiable, implicit, or simulator-based likelihoods. Extensions to score-free or gradient-free settings (e.g., SPSA, likelihood-free/ABC, finite-difference robustness) and their guarantees are not explored.

- General noise models and robustness: The theory and examples emphasize Gaussian noise. It is unclear how the method behaves under heavy-tailed, discrete, misspecified, or heteroscedastic noise models, and what structural conditions on ρ or ℓ_y are sufficient for the convergence results to hold.

- Hyperparameter selection without curvature estimates: The paper recommends small T (and suitable S) but provides no practical procedure to select these based on problem-dependent curvature or log-Sobolev/Poincaré constants, which are typically unknown in high dimensions.

- Preconditioning and condition number control: While the theory “reveals the influence” of the problem’s condition number, the algorithm does not include preconditioning, geometry-aware metrics, or tempering to mitigate ill-conditioning, nor provide guidance on how to implement such accelerations with guarantees.

- Discrete-time corrections and exactness: The inner/outer Langevin processes are unadjusted (no Metropolis correction). There is no analysis of bias accumulation from unadjusted discretization, and whether accept–reject corrections or auxiliary tempering could improve exactness while preserving plug-and-play modularity.

- Reusability and amortization of D(t, x, y): The method estimates D via on-the-fly Monte Carlo per (t, x, y). There is no exploration of amortized denoiser models (e.g., neural networks approximating D) with error bounds, caching/recycling strategies across timesteps, or low-rank/structure-exploiting accelerations.

- Uncertainty quantification calibration: While empirical uncertainty quantification is demonstrated, there is no formal assessment of calibration (coverage, sharpness, miscalibration metrics) or guarantees relating Wasserstein error bounds to downstream UQ quality (e.g., credible set coverage).

- Prior–likelihood mismatch: The plug-and-play prior is trained independently of the likelihood; the paper does not analyze how mismatch between training data and the measurement model impacts posterior accuracy, nor provide methods to detect or correct mismatch at inference time.

- Extensions to hierarchical models and unknown noise scales: Many inverse problems require inferring nuisance parameters (e.g., noise variance). The framework does not address joint posterior sampling over (X₀, θ), nor provide a strategy for marginalization or alternating updates compatible with the proposed diffusion path.

- Diagnostics and stopping criteria: Practical diagnostics for convergence of the inner Langevin chains (RGO) and the reverse process are not specified, nor are stopping criteria, effective sample size measures, or tests for residual bias in the posterior samples.

- Theoretical constants and practicality: Error bounds likely depend on hard-to-estimate functional inequalities (e.g., LSI/PI) for q_t and p_t. Methods to estimate these constants in practice, or surrogate diagnostics to inform hyperparameters and trust in the bounds, are not provided.

- Applicability beyond Euclidean domains: The method assumes Euclidean signals and gradients. Extensions to manifold-valued data (e.g., rotations, shapes), constraints, or convex sets (e.g., positivity) and their implications for the RGO and reverse process are not addressed.

Glossary

- 2-Wasserstein distance: A metric on probability distributions measuring optimal transport cost under squared Euclidean distance. "establishing error bounds in the 2-Wasserstein distance."

- Annealed Langevin dynamics: A sampling method that runs Langevin dynamics across a sequence of noise scales to improve mixing. "the Langevin dynamics with such score has also be investigated in the literature of annealed Langevin dynamics"

- Bayesian inverse problems: Inferring unknown signals from noisy, indirect measurements via Bayes’ rule. "stability and well-posedness of Bayesian inverse problems"

- Brownian motion: A continuous-time stochastic process with Gaussian increments, used as the driving noise in SDEs. "is a -dimensional Brownian motion"

- Classifier-free guidance: Conditioning technique for diffusion models that learns conditional scores directly without an auxiliary classifier. "In contrast, classifier-free guidance~\citep{ho2022classifier} eliminates the need for an external classifier"

- Classifier guidance: Conditioning technique that uses a trained classifier to modify the diffusion sampling direction toward a desired condition. "Classifier guidance~\citep{dhariwal2021diffusion}"

- Condition number: A measure of problem ill-conditioning affecting convergence and error amplification. "the condition number of the Bayesian inverse problem"

- Consistency models (CM): Generative models enforcing consistency constraints; used here as learned priors. "consistency-model (CM) priors"

- Dirac delta approximation: Approximating a conditional density by a point mass at its conditional expectation. "Dirac delta approximation"

- Denoising density: The conditional density of the clean variable given its noisy version in a diffusion process. "the denoising density "

- Denoising score matching: A training objective that learns the score (gradient of log-density) using corrupted-clean pairs. "denoising score matching~\citep{vincent2011connection}"

- Diffusion models: Generative models based on a forward noising process and reverse-time sampling using learned scores. "diffusion models~\citep{ho2020denoising,song2021scorebased}"

- Flow-based models: Generative models that parameterize invertible probability transports with tractable densities. "flow-based models~\citep{lipman2023flow,albergo2023building,albergo2025stochastic}"

- Gaussian Approximation: Approximating a target or conditional distribution with a Gaussian, often for tractability. "Gaussian Approximation"

- Gaussian convolution: Smoothing a distribution by convolving it with a Gaussian kernel. "is a Gaussian convolution of "

- Gaussian mixture: A distribution formed by a weighted sum of Gaussian components, often multimodal. "Gaussian mixture can be multi-modal"

- Inference-time alignment: Adjusting generation at sampling time to match observed conditions without retraining. "a procedure referred to as inference-time alignment"

- Jensen's gap: The bias introduced when interchanging expectations with nonlinear functions due to convexity/concavity. "Jensen's gap"

- Langevin dynamics: An SDE-driven sampling method that uses gradient information to target a desired distribution. "particles are generated using Langevin dynamics"

- Log-concavity: Property where the log-density is concave, yielding unimodality and strong convergence guarantees. "rely on the log-concavity of the target distribution"

- Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC): A class of algorithms for sampling from complex distributions using Markov chains. "Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods"

- Maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimator: The mode of the posterior distribution used as a point estimate. "the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimator"

- Monte Carlo estimator: An estimator computed via random sampling and averaging. "we develop a Monte Carlo estimator"

- Normalizing flows (NFs): Invertible neural networks that transform a base distribution into a target with tractable likelihoods. "normalizing flows (NFs)"

- Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process: A mean-reverting Gaussian diffusion process used as the forward corruption mechanism. "Consider the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process as the forward process:"

- Parallel tempering: An MCMC technique that swaps states among chains at different temperatures to improve exploration. "parallel tempering~\citep{Dong2022Spectral}"

- Plug-and-play (PnP): A modular framework that integrates learned priors or denoisers into inverse problem solvers. "plug-and-play (PnP) framework"

- Plug-in gradient estimator: Using the gradient of an approximate function as a surrogate for the true gradient. "plug-in gradient estimator"

- Posterior denoising density: The conditional density of the clean signal given the noisy state and the measurement. "the posterior denoising density "

- Posterior score: The gradient of the log posterior (or conditional) density with respect to the variable. "How can we estimate the posterior score"

- Probability transport: A continuous mapping/path that pushes a simple distribution to a complex target. "constructs a probability transport from an easy-to-sample terminal distribution to the target posterior"

- Restricted Gaussian oracle (RGO): A sampling target combining a quadratic term with the original potential to enhance log-concavity. "is known as the restricted Gaussian oracle (RGO)"

- Sequential Monte Carlo: Particle-based methods that use importance sampling and resampling to approximate target distributions. "sequential Monte Carlo methods"

- Semi-log-concavity: A relaxed concavity condition where the log-density’s Hessian is bounded above modulo a constant shift. "Semi-log-concavity of the posterior"

- Sliced score matching: A score-learning objective that uses random projections to reduce variance and complexity. "sliced score matching~\citep{song2020Sliced}"

- Split Gibbs samplers: Gibbs sampling variants that split variables or factors to enable efficient conditional updates. "split Gibbs samplers"

- Time-reversal process: The reverse-time SDE that transforms the terminal density back to the target distribution. "The time-reversal process"

- Tikhonov regularization: Classical quadratic regularization used to stabilize ill-posed inverse problems. "Tikhonov regularization"

- Tweedie's formula: An identity linking the posterior mean to the score of the marginal distribution. "Tweedie's formula~\citep{Robbins1992Empirical}"

- Unadjusted Langevin Algorithm (ULA): The discretized form of Langevin dynamics without a Metropolis correction step. "Unadjusted Langevin Algorithm (ULA)"

- Warm-start strategy: Initializing sampling from a distribution closer to the target to improve efficiency and convergence. "using a warm-start strategy to initialize the particles"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are actionable use cases that can be deployed now, leveraging the paper’s plug-and-play diffusion posterior sampling (PDPS) with learned priors, Monte Carlo posterior score estimation via Langevin dynamics, and warm-start initialization. These are most mature when the prior score model has already been trained on representative data and the forward model/likelihood is differentiable.

- Healthcare: uncertainty-aware medical image reconstruction (MRI, CT, PET)

- Description: Replace heuristic PnP-diffusion reconstructions with PDPS to produce posterior samples, pixel-wise credible intervals, and mode-aware reconstructions for tasks like low-dose CT, accelerated MRI, and PET denoising/deblurring.

- Tools/Workflows: Integrate PDPS sampler into existing pipelines (e.g., MONAI, TorchIO) with a pre-trained medical image prior; add uncertainty dashboards for radiologists; export per-patient credible maps.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Availability of a representative prior score network trained on modality-specific data; known or well-specified noise model; differentiability of the measurement model; compute for inner-loop Langevin and warm-start sampling at small terminal time T.

- Industrial NDT and manufacturing QA: posterior-sampling deblurring/denoising for X-ray/ultrasound inspections

- Description: Apply PDPS to detect defects with uncertainty quantification in non-destructive testing (e.g., welds, composites) under complex, possibly non-Gaussian noise.

- Tools/Workflows: Drop-in PDPS module within inspection software; generate sample ensembles and anomaly scores; support operator decision-making with credible bounds.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Trained prior on domain imagery; differentiable forward physics; the RGO log-concavity regime accessible by choosing small T.

- Microscopy and astronomy: posterior sampling for deconvolution and nonlinear imaging

- Description: Use PDPS for fluorescent microscopy, confocal deconvolution, and astrophotography denoising/deblurring with trustworthy UQ, especially in low-photon or nonlinear settings.

- Tools/Workflows: Integrate with ImageJ/Fiji or Napari via a PDPS plugin; provide sample-based PSF deconvolution outputs with error bars.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Accurate forward operator (PSF) and noise model; prior trained on relevant specimen/sky images; differentiable likelihood.

- Remote sensing and satellite imaging: robust restoration with UQ under varying noise/blur

- Description: Deploy PDPS for satellite image deblurring/denoising and super-resolution with per-pixel uncertainty and multi-modal posterior exploration (e.g., cloud occlusions).

- Tools/Workflows: Pipeline integration in EO toolkits (e.g., ESA SNAP, GDAL + PyTorch); export georeferenced uncertainty layers for downstream analytics.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Learned prior on satellite domains; availability of likelihood gradients; computational budget for PDPS inner loop.

- Forensics and computational photography: deblurring/denoising with confidence measures

- Description: Use PDPS to restore motion-blurred or noisy photos and generate confidence heatmaps, improving trust in forensic analysis and photo enhancement.

- Tools/Workflows: Desktop/mobile prototype with PDPS-powered PnP solver; present multiple plausible reconstructions for ambiguous content.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Prior trained on relevant image distributions (faces, scenes); adequate device compute or server-side processing; known or approximated noise model.

- Bayesian data assimilation at moderate scale (earth sciences, environmental monitoring)

- Description: Integrate PDPS into small-to-medium scale assimilation tasks (e.g., air quality nowcasting, local hydrology) to provide posterior ensembles without retraining for each sensor model.

- Tools/Workflows: Use PDPS with existing assimilation frameworks (e.g., replacing heuristic steps in 3D-Var/EnKF for specific sub-modules) when forward models are differentiable.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Differentiable/surrogate forward models; trained priors on state fields; compute for Monte Carlo and warm-start steps; start with limited-dimensional systems.

- Academic research: baseline for posterior samplers in multimodal inverse problems

- Description: Employ PDPS as a benchmark method with non-asymptotic 2-Wasserstein guarantees for multi-modal posteriors; ablate warm-start, inner-loop horizon S, and condition number effects.

- Tools/Workflows: Release PDPS module in open-source libraries (e.g., PyTorch, JAX); integrate in reproducibility suites; use provided GitHub repo as a starting point.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Access to prior training data and compute; selection of small T consistent with RGO log-concavity results; differentiable likelihoods.

- Software engineering: plug-and-play posterior sampler module for inverse problems

- Description: Package the MC-based posterior score estimator and warm-start strategy as a reusable component that consumes a pre-trained score network and a user-specified likelihood.

- Tools/Workflows: PDPS-SDK with simple APIs: set_prior_score(), set_forward_model(), sample_posterior(y); include automatic T and S heuristics guided by theory.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Prior score quality; convergence-sensitive hyperparameters (terminal time T, inner-horizon S, step sizes); gradient availability or proximal operators.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require further research, scaling, engineering, or infrastructure (e.g., larger compute, broader priors, real-time constraints) before routine deployment.

- Real-time state estimation in robotics and autonomous systems with UQ

- Description: Use PDPS for SLAM/sensor fusion with learned scene/map priors to sample multi-modal posteriors and quantify localization uncertainty online.

- Tools/Workflows: Hardware-accelerated PDPS kernels; approximate or amortized inner-loop sampling; integration with Robot Operating System (ROS).

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Tight latency budgets; differentiable sensor models; domain-specific priors; methods for non-differentiable likelihoods (proximal/score surrogates).

- Large-scale PDE-constrained inverse problems (seismic, subsurface, reservoir modeling)

- Description: Apply PDPS to high-dimensional geophysical inversions with expensive forward solvers to obtain posterior ensembles and credible intervals.

- Tools/Workflows: Surrogate modeling (PINNs, reduced-order models) for differentiable likelihoods; HPC orchestration for inner-loop Langevin; adaptive S scheduling.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Accurate surrogates balancing bias/variance; scalable prior training on domain data; efficient warm-start samplers; engineering to handle multimillion-dimensional states.

- Energy systems and grid state estimation with uncertainty guarantees

- Description: Use PDPS to fuse SCADA/PMU data with learned priors of grid states/topologies to generate posterior samples for robust operations planning.

- Tools/Workflows: Integration into EMS/SCADA software; UQ-aware contingency analysis; sample-based risk metrics.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Differentiable grid models; priors capturing seasonality/operating regimes; cyber-secure deployment; compute provisioning.

- Clinical decision support and regulatory adoption of UQ in imaging AI

- Description: Standardize posterior-based UQ in radiology reports (credible intervals, multiple plausible reconstructions) to improve safety and trust.

- Tools/Workflows: Validation studies comparing PDPS-UQ against ground truth; calibration metrics; integration with PACS/RIS; guidelines for reporting uncertainty.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Regulatory pathways; clinical trials; robust priors across demographics; interpretability/communication of multi-modal outputs.

- Digital twins with rigorous UQ across manufacturing and infrastructure

- Description: Use PDPS to update high-fidelity digital twins with streaming sensor data, delivering posterior ensembles for predictive maintenance and control.

- Tools/Workflows: Twin platforms instrumented with PDPS posterior sampling; dashboards showing credible forecasts; automated alerts conditioned on posterior risk.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Differentiable twin models or surrogates; streaming compute; priors trained on historical twin states; data governance.

- Probabilistic programming and Bayesian ML backends

- Description: Incorporate PDPS as a posterior sampler inside PPLs for high-dimensional inverse problems where priors are learned via diffusion models.

- Tools/Workflows: Backends for Pyro, NumPyro, or Stan-like systems with score-based priors; APIs for hybrid PnP-diffusion and MCMC/SMC combinations.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Interfacing score networks with PPL graphs; gradient plumbing; convergence diagnostics adapted to PDPS.

- Privacy-preserving and federated learned priors

- Description: Train prior score networks via federated or differential privacy techniques to enable PDPS in sensitive domains (health, finance).

- Tools/Workflows: Federated training pipelines; DP-optimized score matching; certification of privacy-utility trade-offs.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Availability of collaborative cohorts; impact of DP noise on prior score accuracy and downstream PDPS convergence.

- Handling non-differentiable or discrete likelihoods at scale

- Description: Extend PDPS to settings with non-differentiable forward models via proximal Langevin, smoothing, or surrogate gradients.

- Tools/Workflows: Proximal operators or learned differentiable approximations; hybrid split samplers; adaptive selection of T/S satisfying log-concavity conditions.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Quality of proximal/surrogate components; theoretical guarantees for extended setups.

- Automated experimental design and active acquisition

- Description: Use PDPS posterior ensembles to evaluate information gain and optimize sensor placements or acquisition parameters.

- Tools/Workflows: Loop-in posterior-guided acquisition (e.g., MRI k-space trajectories, adaptive microscopy); decision policies based on entropy/variance reduction.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Fast, amortized PDPS or surrogates; cost-aware design objectives; reliable priors matching planned acquisitions.

- Consumer-grade computational photography with trustworthy UQ

- Description: Bring PDPS-based deblurring/denoising to smartphones/cameras with confidence overlays and multiple plausible outputs for user selection.

- Tools/Workflows: On-device optimized priors; GPU/NPU acceleration; UI/UX for uncertainty.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Edge compute limits; energy constraints; curated prior training sets representative of device use-cases.

- Standardization and policy for UQ reporting in AI-driven reconstructions

- Description: Develop policies requiring uncertainty reporting and audit trails for AI reconstructions in public-sector imaging (e.g., satellite, environmental monitoring).

- Tools/Workflows: UQ benchmarks; compliance test suites; documentation templates.

- Dependencies/Assumptions: Consensus standards; stakeholder engagement; reproducible PDPS implementations.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Learned prior score quality: Effectiveness depends on a prior trained on representative data; domain shift reduces fidelity.

- Likelihood specification: Requires known noise model and differentiable forward operators (or proximal/surrogate alternatives).

- Hyperparameters: Terminal time T must be small enough to ensure RGO log-concavity and stable posterior score estimation; inner-loop horizon S balances bias/compute.

- Compute: Inner Monte Carlo via Langevin and warm-start sampling incur non-trivial costs; acceleration (GPU, mixed precision, batching) improves practicality.

- Multimodality: PDPS is designed to handle multi-modal posteriors; ensure the learned prior captures mode structure relevant to the task.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.