ToC: Tree-of-Claims Search with Multi-Agent Language Models (2511.16972v1)

Abstract: Optimizing patent claims is a critical yet challenging task, demanding careful balance between maximizing novelty and preserving legal scope. Manual claim drafting is labor-intensive, costly, and inherently inconsistent, while conventional LLMs often lack the structured, iterative reasoning essential for precise claim refinement. To address these challenges, we introduce Tree of Claims (ToC), an innovative framework that redefines claim editing as a guided search problem. ToC synergistically integrates Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) with a collaborative multi-agent system, comprising an LLM-based EditorAgent that proposes contextually grounded edits, and an ExaminerAgent that mimics patent examiner critiques through structured, chain-of-thought analyses of novelty and prior art disclosure. Driven by a carefully designed multi-objective reward function, ToC jointly optimizes novelty, scope retention, and semantic coherence. Experimental evaluation on a benchmark of 1145 claims demonstrates that ToC significantly outperforms standard LLMs in zero-shot and few-shot scenarios, achieving an average composite score improvement of 8\%, and up to 9\% in certain cases. Extensive experiments, including detailed ablation studies, validate ToC's efficacy in generating superior, legally robust claim revisions. Overall, ToC establishes a transparent, controllable, and interpretable methodology that effectively bridges advanced LLM reasoning capabilities with strategic MCTS planning for structured patent claim optimization.The source code is available at https://github.com/ysy2003/ToC.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper introduces a new way to improve patent “claims,” which are the legal sentences that define exactly what an invention covers. Writing strong claims is hard because they must be:

- New compared to older inventions (called “prior art”),

- Clear and legally correct,

- Broad enough to protect the invention, but not too broad to be rejected.

The authors propose a system called ToC (Tree-of-Claims). It uses advanced AI tools to edit claims step-by-step, like exploring different paths in a decision tree, to make them better—more novel, well-structured, and legally safe.

Key Objectives: What did the researchers want to find out?

The paper focuses on three simple questions:

- Can AI improve patent claims more reliably by using a careful, step-by-step planning process instead of one-shot text generation?

- Can two specialized AI “roles” (one editing, one checking) work together to make better claim revisions?

- Does the system actually outperform standard LLMs on real patent tasks?

Methods: How does the system work?

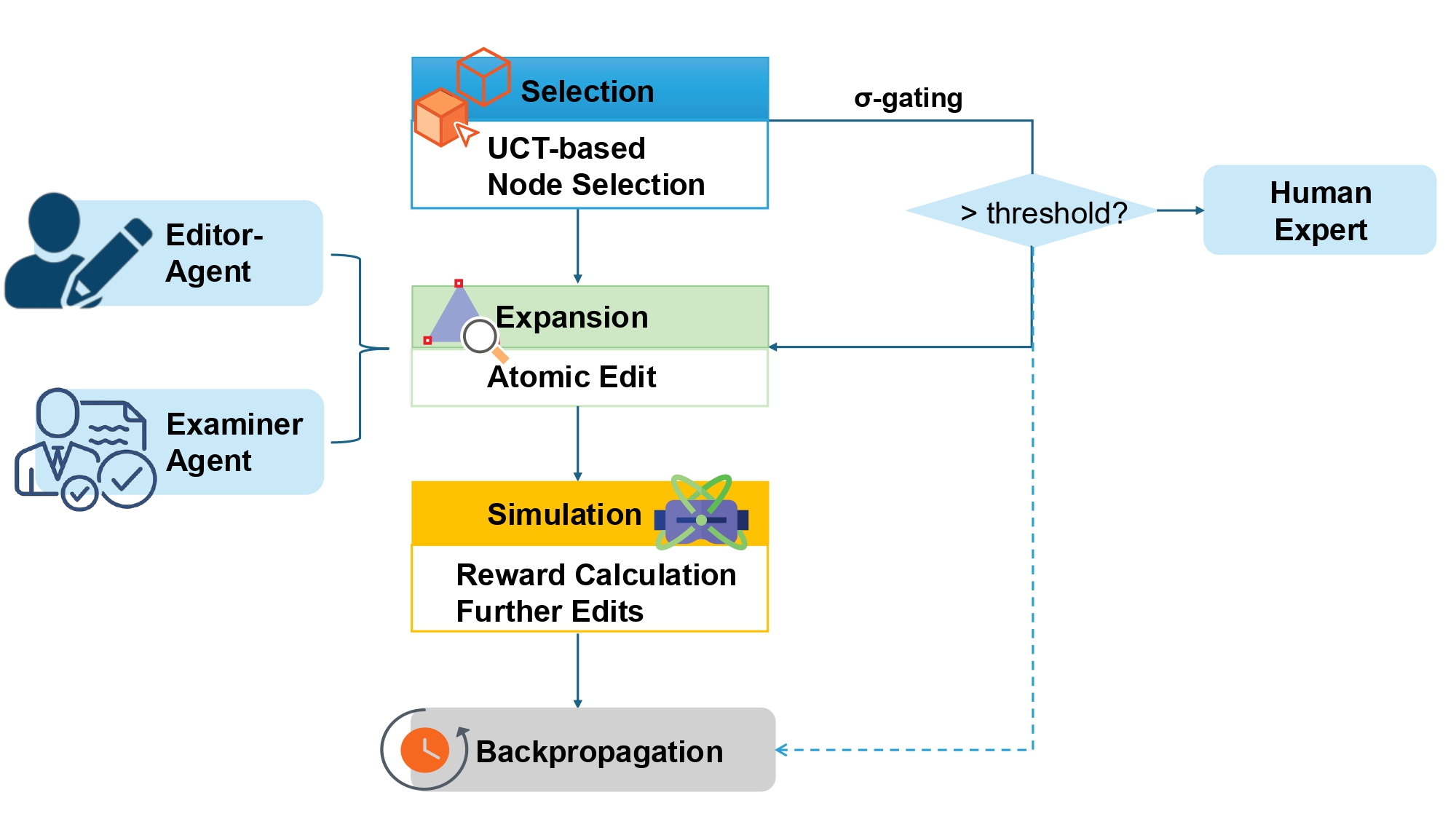

Think of ToC as a smart team that edits a claim by testing different “moves” and picking the best path. Here’s how:

The Big Idea: Search like a tree

- Imagine you’re playing a strategy game. At each turn, you try different moves and look a few steps ahead to see which move leads to the best outcome.

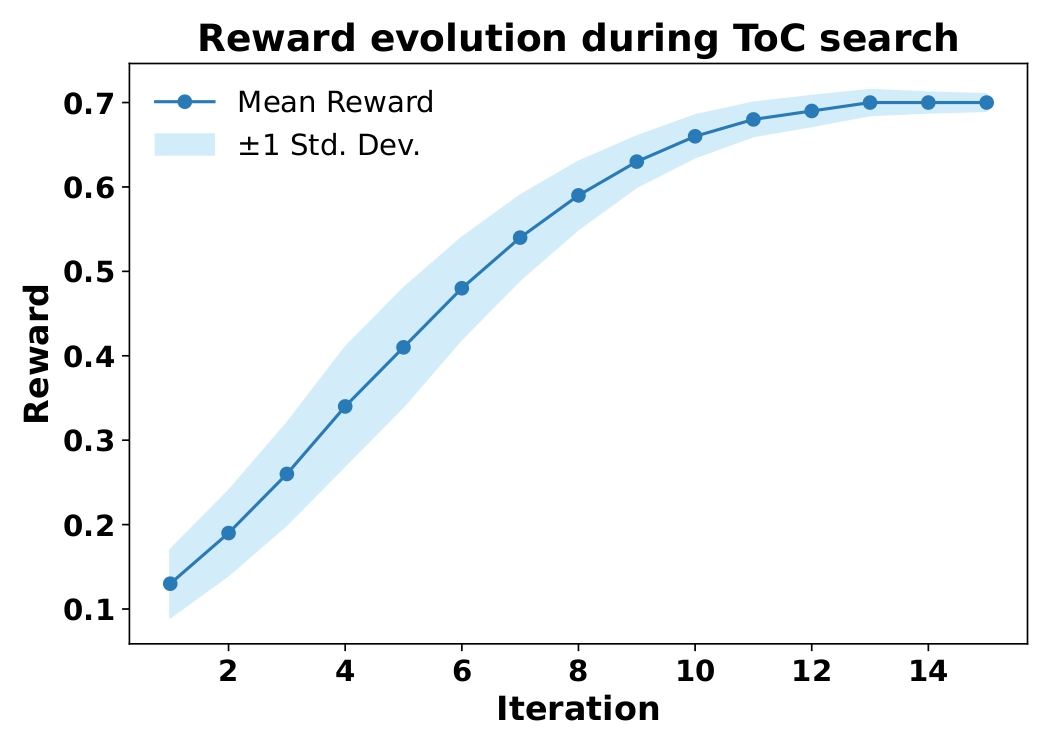

- ToC does this for claim editing using a method called Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). It builds a “tree” of possible edit sequences and explores them to find the best set of changes.

Two AI Teammates: A writer and an examiner

ToC uses two specialized AI roles:

| Agent | What they do | In simple terms |

|---|---|---|

| EditorAgent | Suggests specific edits to the claim | Like a careful writer who makes small, controlled changes |

| ExaminerAgent | Checks each edit against prior art for novelty and clarity | Like a patent examiner giving detailed feedback with evidence |

They work in a loop: the Examiner reviews, the Editor revises, and the search continues until the claim is improved.

Safe and Smart Choices: Avoid risky edits

ToC includes extra safety checks:

- It measures “uncertainty” (how unsure the AI is). If uncertainty is too high, it stops or flags the edit.

- It uses “progressive widening,” which means it starts with a few promising edits and only adds more options as it gains confidence—like widening the search slowly to stay in control.

Scoring System: How edits get judged

Each edit—and the final claim—is scored using multiple goals:

- Novelty: Is it more original compared to prior art?

- Scope: Does it keep the invention properly protected (not too narrow)?

- Consistency: Does the claim stay clear, legal, and technically coherent?

- Risk: Are we avoiding edits the AI is uncertain about?

The system balances these goals to pick the best path through the edit tree.

Main Findings: What did they discover?

The researchers tested ToC on real patent data (over 1,100 patents and 28,000 claims) and compared it to strong LLMs like GPT-4o and others. Key results:

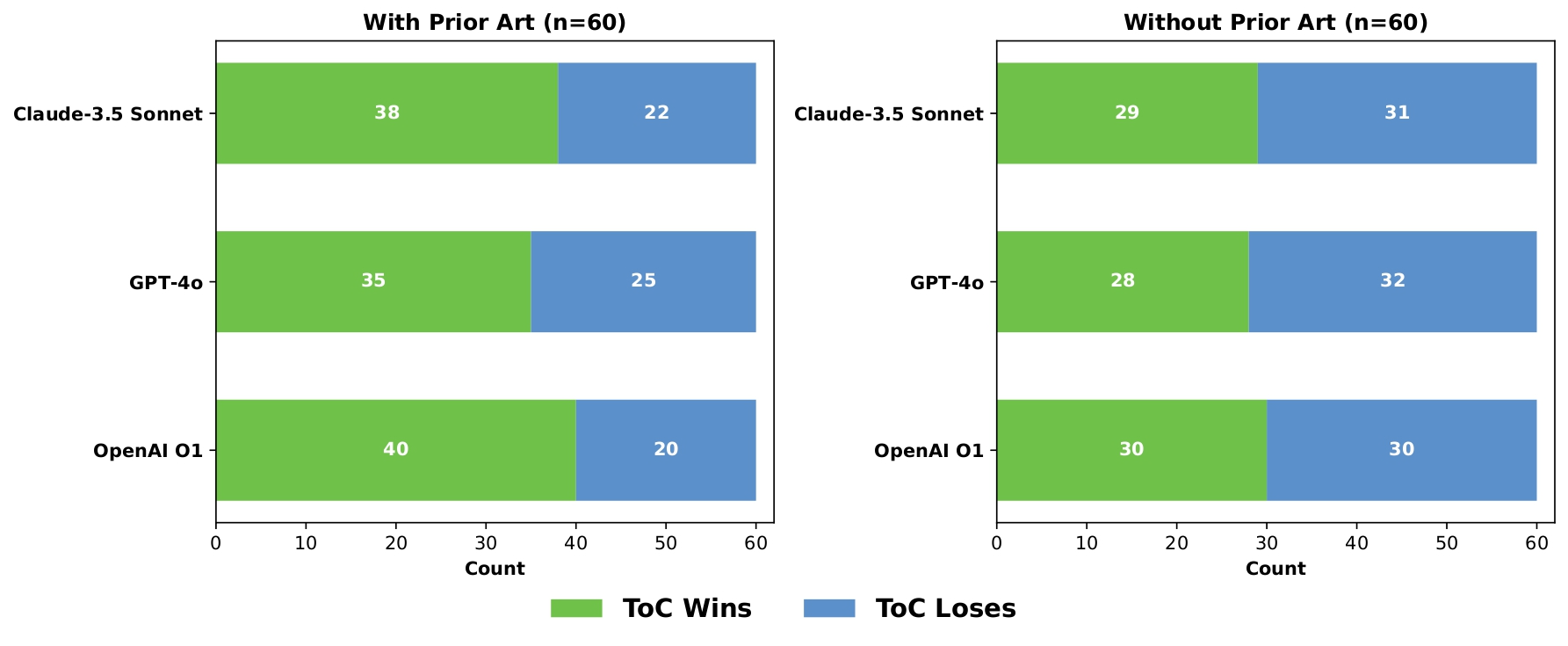

- ToC improved the overall quality score of revised claims by about 8% on average, and up to 9% in some cases.

- It consistently beat standard “zero-shot” and “few-shot” LLM methods (which rely on single prompts or short examples).

- Human experts preferred ToC’s revised claims about two-thirds of the time when prior art was available.

- The system worked well across multiple AI models, including both closed-source (GPT-4o) and open-source (Qwen2.5-VL), showing it’s flexible and reliable.

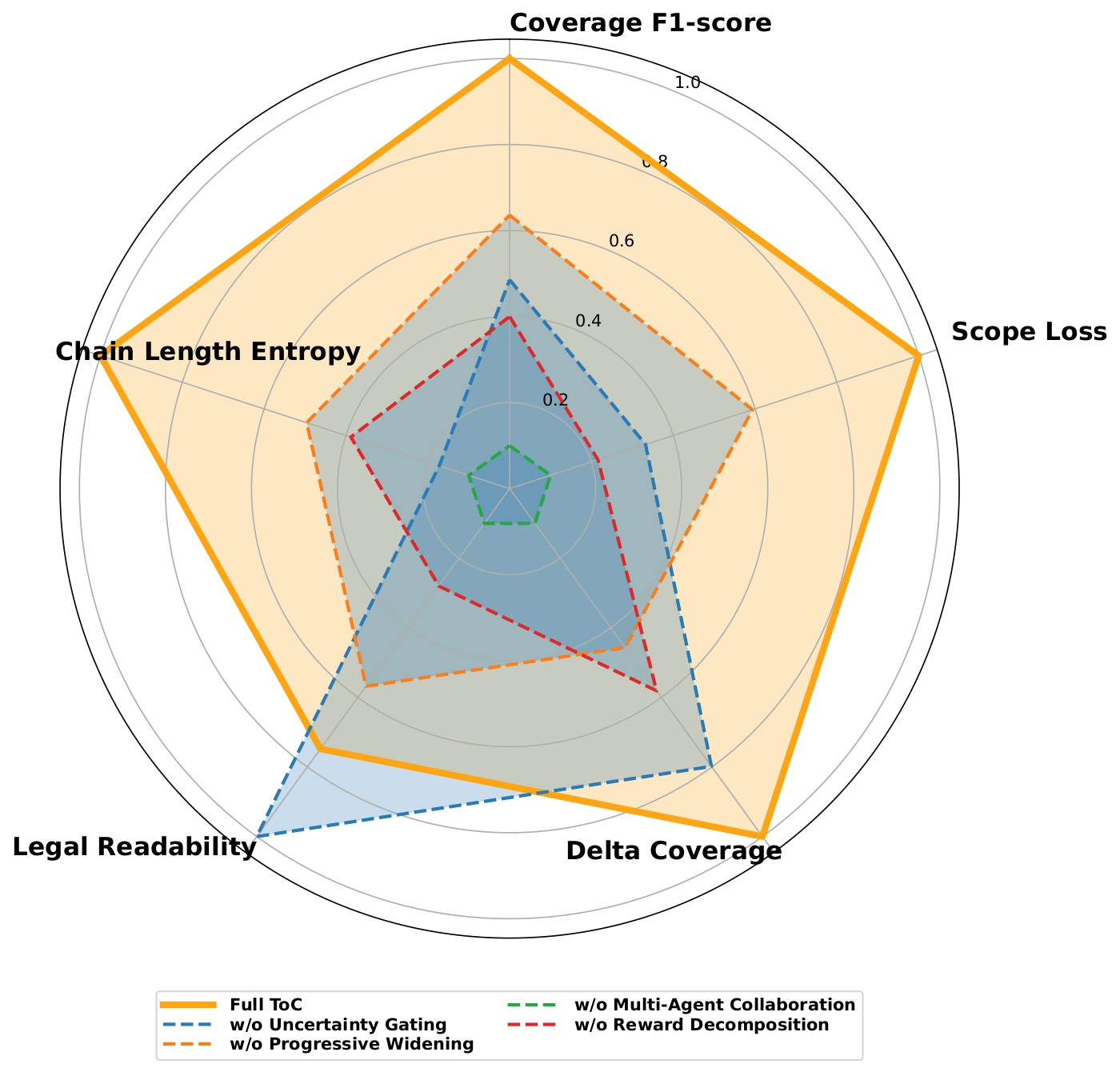

- Turning off important components (like uncertainty control or the two-agent collaboration) made performance worse, proving these parts really matter.

Why This Matters: Impact and future possibilities

Strong patent claims protect inventions and can affect business value, licensing, and legal outcomes. ToC helps by:

- Making claim editing more transparent and controllable (every change is small, justified, and tracked).

- Saving time and cost compared to manual revisions.

- Reducing mistakes by checking novelty and legal clarity at each step.

- Providing a practical way to combine AI’s language skills with careful planning and review.

Beyond patents, the same approach could improve other high-stakes writing tasks—like legal contracts, medical guidelines, or scientific methods—anywhere you need careful, rule-following edits with clear reasoning. The authors plan to add better image/figure understanding, speed up the search, and apply ToC to more domains.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to guide future research.

- Generalizability across domains: Results are limited to wireless communications and 2016 USPTO office actions; it remains unclear whether ToC transfers to other technical fields (e.g., biotech, chemical, mechanical) and newer prosecution norms.

- Jurisdictional validity: No evaluation against EPO, JPO, CNIPA, or other jurisdictions with different novelty/obviousness standards and claim-drafting conventions.

- Real-world prosecution outcomes: Absence of prospective or retrospective validation linking ToC revisions to actual allowance rates, office action reductions, or time-to-grant in live filings.

- New matter and written description compliance: Operations like

AddNovelFeaturerisk introducing unsupported claim elements under 35 U.S.C. §112(a); there is no mechanism to verify edits against the specification for new matter avoidance. - Formal claim drafting constraints: No automatic checks for antecedent basis, means-plus-function under §112(f), Markush group correctness, or clarity under §112(b).

- Prior art coverage breadth: The system relies on examiner-cited prior art and Google Patents scraping; it does not perform comprehensive prior-art search (including non-patent literature) or measure recall/precision of retrieved evidence.

- Evidence alignment quality: The pipeline for mapping claim sub-elements to prior art evidence lacks quantitative validation (e.g., precision/recall, error rates) and inter-annotator agreement metrics for expert reviews.

- ExaminerAgent validity: The model-simulated examiner judgments are not benchmarked against real examiner decisions or gold-standard annotations; risk of circular evaluation when novelty and coverage are scored by the same LLM agents that propose edits.

- Novelty metric externality: “Novelty” is assessed internally by the ExaminerAgent; there is no external metric grounded in doctrinal tests (e.g., anticipation under §102, obviousness under §103) or standardized legal rubrics beyond limited human preference ratings.

- Human evaluation robustness: Expert evaluations involve five specialists without reported inter-rater reliability (e.g., Cohen’s kappa), sampling protocols, or stratified analysis across claim types (independent vs dependent; method vs apparatus).

- Claim-type sensitivity: No breakdown of performance by claim categories (independent/dependent, apparatus/system/method, computer-readable medium), which often exhibit distinct editing constraints and examiner scrutiny.

- Scope preservation measurement: Scope retention is proxied by text similarity/scope similarity; there is no validated semantic or formal coverage metric (e.g., model-theoretic coverage, structured element containment) to ensure legal scope is truly maintained.

- Uncertainty calibration: Epistemic/aleatoric decomposition uses

σ_ale = 1 − confidencefrom LLM outputs; no calibration analysis (e.g., ECE/Brier scores), threshold sensitivity studies across models, or comparison with alternative UQ methods (ensembles, Bayesian decoding). - Gating threshold selection: The

σ_epi^max = 0.2threshold is “tuned,” but lacks a systematic, cross-model, cross-domain sensitivity analysis or principled selection (e.g., ROC-based operating points, risk-cost trade-offs). - Reward-weight robustness: Multi-objective weights

(w1..w5)are “empirically derived” without principled optimization (e.g., Pareto front analysis, scalarization tuning, meta-learning) or domain-specific customization protocols. - Search algorithm comparisons: MCTS is not compared against alternative structured search methods (beam/A*/PUCT, evolutionary strategies, policy gradient/RL, tabu/ILP-based editing), nor is there a theoretical convergence or optimality analysis under uncertainty gating and progressive widening.

- Computational cost and practicality: No reporting of runtime per claim, memory footprint, token usage, or economic cost (API fees) across models; unclear feasibility for law-firm workflows and large dockets.

- Multi-agent role specialization: Limited exploration of heterogeneous agent pairs (e.g., strong ExaminerAgent + weaker EditorAgent) or cross-model pairings; no analysis of how role specialization affects outcomes.

- Failure mode mitigation: Frequent errors (unsupported novelty, invalid modifications, system control failures) are documented but not linked to targeted corrective mechanisms (e.g., structural validators, hard constraints, post-edit legal checks).

- Long-context and document-length robustness: The paper does not assess performance on very long claims or extensive prior art, nor discuss context-window limits and summarization strategies for scalable reasoning.

- Image/figure-grounded edits: While VL models are used and

ReframeViaFigureis defined, the paper lacks concrete quantitative evaluation of image–text reasoning (e.g., figure relevance accuracy, figure-grounded novelty gains). - Dataset reproducibility: Prior art retrieval via Google Patents scraping may be brittle; no release of cleaned/linked datasets, evidence alignment ground truth, or reproducible pipelines to ensure consistent replication.

- Imbalanced data handling: The dataset is heavily imbalanced (allowed vs rejected), yet there is no strategy to mitigate bias (e.g., reweighting, stratified evaluation) or analyze differential performance across label strata.

- Safety and compliance: No discussion of confidentiality risks in using closed-source APIs, auditability, or compliance with professional responsibility and client data protection in real legal settings.

- Generalization beyond patents: Although future work mentions contracts and protocols, the paper does not specify which components transfer, how reward terms must be adapted, or what legal constraints differ across document classes.

- Human-in-the-loop efficacy: Gating can “trigger human intervention,” but the paper lacks measured impacts of human review loops (e.g., acceptance rate of flagged edits, time-to-resolution, error reduction).

- Token-level determinism: All runs use temperature=0.0; the impact of controlled stochasticity (top-p/top-k) on search diversity, reward optimization, and uncertainty estimation remains unexplored.

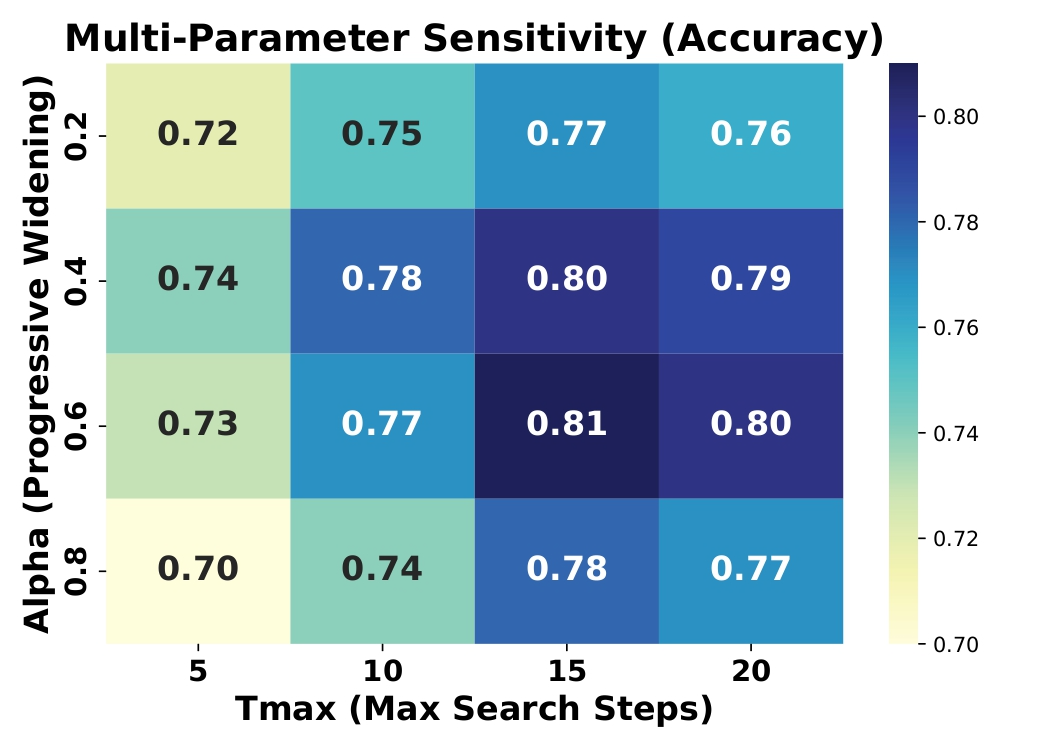

- Progressive widening hyperparameters: Only limited sensitivity is reported; the effect of

δand exploration constantcin UCT is not analyzed, and there is no guidance on tuning these for different agent/model regimes. - Legal-readability scoring: “Legal readability” is included but not methodologically defined or validated against established drafting style guides or expert-labeled corpora.

- End-to-end integration: The work does not show integration with prosecution tooling (IDS management, OA response drafting, claim charts) or compatibility with downstream document assembly and filing systems.

Glossary

- Ablation paper: A controlled experiment where components of a system are removed to assess their individual contributions. "Extensive experiments, including detailed ablation studies, validate ToC's efficacy in generating superior, legally robust claim revisions."

- Aleatoric uncertainty: Uncertainty arising from inherent noise in data or observations, not reducible by more information. "total variance is decomposed into epistemic and aleatoric terms"

- Atomic edit operation: A minimal, indivisible modification to text used as a single action in the search process. "The action space includes ten atomic operations."

- Backpropagation (MCTS): The phase in Monte Carlo Tree Search where simulated rewards are propagated from a leaf back up the tree to update ancestor nodes. "Backpropagation. The reward of the simulated claim is propagated up the path:"

- BLEU: An automatic metric for evaluating text generation quality via n‑gram overlap with references. "as well as ROUGE‑L, BLEU, and expert preference."

- Branching factor: The number of child nodes (possible actions) considered from a given node in a search tree. "progressive widening controls the branching factor as the search deepens:"

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT): An LLM prompting strategy that elicits step‑by‑step reasoning. "a few-shot (2-shot) setting with exemplars and Chain-of-Thought reasoning prompts."

- Coverage F1: A harmonic mean measure of precision and recall used here to evaluate disclosure avoidance coverage. "Core metrics follow our reward terms: coverage F1 and for disclosure avoidance"

- Disclosure analysis: Systematic assessment of whether claim elements are present in prior art, including evidence and confidence. "The ExaminerAgent performs disclosure analysis by examining each claim element against prior art documents,"

- EditorAgent: A specialized LLM agent that proposes legally sound, atomic edits to improve claims. "an LLM-based EditorAgent that proposes contextually grounded edits,"

- Epistemic uncertainty: Uncertainty due to limited knowledge or model uncertainty, reducible with more information. "For each visited node we estimate epistemic variance σ_epi(n)."

- ExaminerAgent: A specialized LLM agent that simulates patent examiner critique with structured reasoning and uncertainty reporting. "an ExaminerAgent that mimics patent examiner critiques through structured, chain-of-thought analyses of novelty and prior art disclosure."

- Human intervention: A control mechanism where high‑uncertainty paths trigger manual review or strategy changes. "Trigger human intervention or strategy switch"

- JSON‑parsing completeness: A robustness metric indicating how consistently models output machine‑readable JSON as required. "we additionally report JSON‑parsing completeness, chain entropy, image–text consistency, legal readability, token‑level perplexity (PPL), as well as ROUGE‑L, BLEU, and expert preference."

- Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS): A planning algorithm that builds a search tree via randomized simulations to optimize decisions under uncertainty. "ToC synergistically integrates Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) with a collaborative multi-agent system,"

- Multi-agent system: A framework where specialized agents collaborate and critique to achieve complex, constrained goals. "A collaborative multi-agent architecture where an EditorAgent generates legally robust edit operations, and an ExaminerAgent provides systematic assessments,"

- Multi-objective reward function: A scoring function that balances multiple goals (e.g., novelty, scope, coherence, risk) into a single scalar. "Driven by a carefully designed multi-objective reward function, ToC jointly optimizes novelty, scope retention, and semantic coherence."

- Multimodal LLMs (MLLMs): LLMs that process and reason over multiple modalities such as text and images. "We evaluate the ToC framework using a diverse set of multimodal LLMs as reasoning agents."

- Office actions: Official communications from patent offices detailing examination results, rejections, or allowances. "LLMs like GPT-4 are increasingly used in patent tasks, from claim drafting to responding to office actions"

- Perplexity (PPL): A token‑level measure of LLM uncertainty; lower values indicate more confident, fluent text. "token‑level perplexity (PPL)"

- Prior art: Existing publications or patents used to assess the novelty of a claim. "maximizing novelty over prior art"

- Prior art disclosure: The extent to which a claim’s elements are already revealed in existing references. "analyses of novelty and prior art disclosure."

- Progressive widening: An MCTS technique that gradually increases considered child actions as node visits grow, controlling tree growth. "we apply progressive widening"

- Progressive‑widening coefficient α: The parameter controlling how quickly the number of explored children increases with visits. "the progressive‑widening coefficient α (rows)"

- Rollout (MCTS): A simulation from a node to produce a complete outcome used for estimating rewards. "we roll out a complete claim using a rule‑guided policy"

- ROUGE‑L: A text evaluation metric based on longest common subsequence overlap between system and reference outputs. "as well as ROUGE‑L, BLEU, and expert preference."

- Scope narrowing: Unintended reduction of a claim’s legal coverage due to added constraints or edits. "scope penalises unnecessary narrowing;"

- Scope preservation: Maintaining the original claim’s legal coverage while making improvements. "including novelty, scope preservation, legal readability, and human preference."

- Semantic coherence: Logical and meaning-level consistency across edited text. "semantic coherence."

- Sigma‑gating (σ‑Gating): A pruning strategy based on uncertainty thresholds to avoid committing to highly uncertain edits. "σ‑Gating. For each visited node we estimate epistemic variance σ_epi(n)."

- Tree-of-Claims (ToC): The proposed framework that treats claim editing as structured search with collaborating agents. "We introduce Tree of Claims (ToC), an innovative framework that reconceptualizes patent claim editing as a structured search process."

- Tree-of-Thoughts: A reasoning framework that explores multiple paths to improve problem-solving with LLMs. "MCTS also underpins frameworks like Tree-of-Thoughts \cite{yao2023tree}, which explore multiple reasoning paths for complex problem-solving."

- Uncertainty-aware MCTS: An MCTS variant that models and uses uncertainty estimates to guide search and pruning. "The ToC framework employs an uncertainty‑aware MCTS architecture,"

- Upper Confidence Bound for Trees (UCT): The selection rule in MCTS balancing exploitation and exploration via confidence bounds. "Starting at the root, the search descends by repeatedly choosing the child with the highest UCT score"

- Variance decomposition: Splitting total uncertainty into epistemic and aleatoric components for clearer risk control. "total variance is decomposed into epistemic and aleatoric terms,"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.