Training Language Models to Explain Their Own Computations (2511.08579v1)

Abstract: Can LMs learn to faithfully describe their internal computations? Are they better able to describe themselves than other models? We study the extent to which LMs' privileged access to their own internals can be leveraged to produce new techniques for explaining their behavior. Using existing interpretability techniques as a source of ground truth, we fine-tune LMs to generate natural language descriptions of (1) the information encoded by LM features, (2) the causal structure of LMs' internal activations, and (3) the influence of specific input tokens on LM outputs. When trained with only tens of thousands of example explanations, explainer models exhibit non-trivial generalization to new queries. This generalization appears partly attributable to explainer models' privileged access to their own internals: using a model to explain its own computations generally works better than using a different model to explain its computations (even if the other model is significantly more capable). Our results suggest not only that LMs can learn to reliably explain their internal computations, but that such explanations offer a scalable complement to existing interpretability methods.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper explores a simple question: can an AI explain how it thinks? More exactly, it asks whether a LLM (a kind of AI that reads and writes text) can learn to honestly describe the steps and signals inside its “brain” that lead to its answers. The authors test whether a model is better at explaining itself than another, even bigger or stronger, model trying to explain it.

What questions did the researchers ask?

They focused on three easy-to-understand questions about what’s going on inside a model when it makes a decision:

- What does a specific “feature” inside the model look for? Think of a feature like a detector that lights up for certain patterns (for example, city names).

- Which inner parts actually cause the final answer to change if you tweak them? This is like asking: if I edit this “note” in the model’s scratch work, does the conclusion change?

- Which words in the input mattered most for the answer? For example, if you remove a hint from the question, does the model change its answer?

How did they study it?

The team trained “explainer” models to produce short, clear explanations of what’s happening inside a “target” model. Sometimes the explainer and target were the same model (self-explaining); other times, the explainer was a different model.

To do this, they first created trustworthy sets of “right answers” using standard interpretability tests, then fine-tuned the explainers to match those answers.

Here are the three kinds of tests they used, with simple analogies:

1) Explaining features (what a detector looks for)

- Idea: A feature is like a tiny sensor inside the model that turns on for certain tokens (like “Paris” or “NYC”).

- Method: They collected many examples and found which description (like “city names”) best predicted when that sensor fires. They used a separate helper model (a “simulator”) to check how well each candidate description matched the sensor’s real behavior.

- Training: They then taught the explainer to answer, in plain language, “This feature lights up for …” so it could describe new features it hadn’t seen before.

2) Activation patching (what inner parts cause changes)

- Idea: Imagine the model’s thinking as layers of notes. If you copy a note from a different example and paste it into the current one, does the final answer change?

- Method: They took an input (like “Paris is the capital of …”) and swapped in internal activations (notes) from a similar but different sentence (like “Rome is the capital of …”). Then they checked if the predicted country changed (France vs. Italy).

- Training: They taught the explainer to say whether the answer would change and what it would change to.

3) Input ablation (which words matter)

- Idea: If you remove a hint from a multiple-choice question, does the model change its answer?

- Method: They added a simple hint (like “Hint: A”) to a question, checked what the model answered, and then removed the hint to see if the answer changed.

- Training: They taught the explainer to predict if removing the hint would change the answer and, if so, to what.

A few extra notes in everyday terms:

- Fine-tuning: This is like giving the model some extra tutoring with examples and corrections.

- “Privileged access”: A model has special inside knowledge of its own activations (its “heartbeat” or “scratch work”), which might help it explain itself better than an outsider can.

- When models had different “shapes” (sizes or architectures), the authors used a simple “translator” layer so one model could read the other’s internal signals.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Here are the main takeaways:

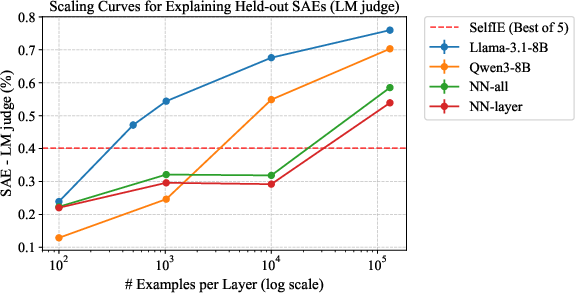

- Models can learn to explain themselves accurately. After a small amount of fine-tuning, models produced useful, faithful explanations of their own inner features and decisions.

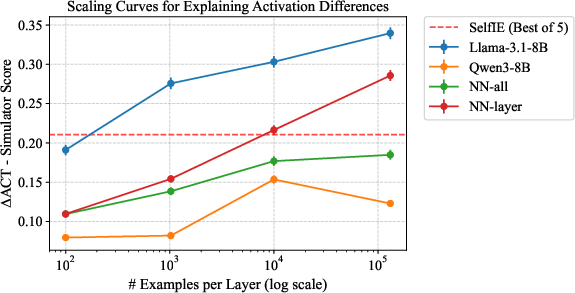

- Self-explanations are often better than outsider explanations. A model explaining itself usually beat even larger or instruction-tuned models trying to explain it. In short: knowing your own mind helps. This supports the “Privileged Access Hypothesis.”

- It’s efficient. Teaching a model to explain itself took far fewer examples than other methods (like nearest-neighbor lookups that copy the most similar past description). In many cases, self-explaining reached strong performance with only a tiny fraction of the data.

- The effect shows up across tasks. The “self is best” pattern appeared for:

- Feature descriptions (what detectors look for).

- Activation patching (what inner parts cause changes).

- Input ablation (what input words matter). Here, some models were just stronger explainers overall, but each model still tended to explain itself better than it explained others.

- Similar models explain each other better. When the explainer and target share architecture or training style, explanations improve. Bigger isn’t always better if the explainer doesn’t “think” in a similar way.

What’s the potential impact?

- Scalable interpretability: Instead of only relying on slow, external tools to probe a model, we can train the model to explain its own inner workings. This could make understanding AI systems faster and cheaper.

- Better debugging and safety: If a model can tell us which inputs and inner parts led to an answer, it’s easier to catch mistakes, detect shortcuts (like overusing hints), and reduce harmful behavior.

- Complements other methods: These self-explanations don’t replace existing interpretability tools—they build on them. But they could help generate trustworthy explanations at scale once a model is trained.

In short, this paper shows that with a bit of targeted training, LLMs can learn to honestly describe what’s going on inside their own “heads”—and they usually do it better for themselves than for others. That’s a promising step toward safer, more transparent AI.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, consolidated list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper. Each point is framed to be concrete and actionable for future research.

- Ground-truth reliability: The method relies on external interpretability artifacts (Neuronpedia SAE labels and a learned simulator) that are noisy and biased; establish independent, high-fidelity ground truth (e.g., human-verified labels, controlled synthetic circuits) and quantify how label noise propagates to explainer training and evaluation.

- Faithfulness measurement: Current metrics (LM-judge similarity and simulator correlation) conflate plausibility with faithfulness; develop causal, model-internal metrics (e.g., counterfactual attribution consistency, logit-based effect sizes) that directly measure whether explanations match the computations that actually determine outputs.

- “Self-explanation” definition: The setup fine-tunes a separate explainer and not the target model; investigate strict self-explanation where the same model provides explanations without changing its output distribution, and quantify the trade-offs between strict and relaxed setups.

- Component coverage: Explaners struggled to describe features from non-residual components (attention heads, MLP neurons, layer norms); design injection/conditioning interfaces and training schemes that let models explain a broader set of internal mechanisms (including attention pathways and subcircuits).

- Intervention granularity: Activation patching aggregates across layer blocks via averaged vectors, reducing causal specificity; evaluate single-layer/position patching, head-level interventions, and path patching, and measure the effect on explanation accuracy and circuit localization.

- Difference metric d(·,·): The paper does not specify a principled, consistent choice of output-change metric for interventions; compare KL divergence, logit deltas, top-k swaps, and calibration-aware metrics, and quantify how each impacts training, evaluation, and conclusions.

- Representation alignment: Privileged access seems mediated by alignment of activations between explainer and target; systematically test alignment methods (CCA/CKA, Procrustes, orthogonal/affine mappings, contrastive pretraining) and measure how alignment strength predicts explainer performance.

- Scale and placement of activation insertion: The explainer relies on inserting v into the embedding layer and is sensitive to scale; conduct a systematic study of insertion location (embedding vs early/mid/late layers), normalization, and magnitude calibration, and learn adaptive scaling policies.

- Polysemantic features: The argmax selection of a single description ignores superposition; develop multi-label or mixture descriptions (with calibrated weights) and evaluate faithfulness on known polysemantic features.

- Task/domain coverage: Evaluations focus on FineWeb, CounterFact, and MMLU hints; probe generalization across domains (multilingual text, code, math, long-context reasoning), harder OOD distributions, and real-world tasks where internal computations are different.

- Input ablation realism: Hint-based multiple-choice ablations are synthetic; create datasets with naturally occurring rationale tokens and long-form reasoning, and assess whether models can detect and verbalize decision-critical spans under realistic conditions.

- Content prediction weakness: Llama-3.1-8B exhibits near-random “content match” on input ablations post-training; analyze failure modes (e.g., inability to predict new top-1 token distributions), and try objectives that directly model next-token distributions or constrained structured outputs.

- Explainer capability confounds: Qwen outperforms Llama across input ablation but privileged access persists; design controlled experiments that disentangle general capability from privileged access by varying architecture, scale, data, and alignment independently.

- Data-efficiency baselines: Comparisons are limited to nearest-neighbor retrieval; benchmark against metric learning, meta-learning, retrieval-augmented generation, and prototype-based methods to contextualize the claimed data efficiency of privileged self-explanation.

- Impact on base capabilities: Fine-tuning for introspective explanation may affect standard LM tasks; measure changes in perplexity, task accuracy, safety/toxicity, and calibration post-training, and explore multi-objective training to mitigate degradation.

- Robustness and adversarial behavior: Assess whether models can strategically mis-explain under adversarial prompts or incentives; build stress tests for explanation robustness and honesty, including distribution shifts, prompt attacks, and deceptive settings.

- Online vs offline introspection: Current methods explain offline queries; explore online self-explanations generated during inference, tied to the exact forward pass that produced the answer, and measure causal consistency across time.

- Human evaluation breadth: LM-judge shows 81% agreement on 200 samples; expand human evaluation (larger, multi-annotator panels), report inter-annotator agreement and error taxonomy, and calibrate LM judges against expert assessments.

- Generalization across models: The study centers on Llama-3.1-8B with limited explorations of Qwen and Llama-70B; extend to diverse architectures (Mixture-of-Experts, decoder-only vs encoder–decoder, multimodal transformers), scales, and training regimens to test the universality of privileged access.

- Feature explainability predictors: Identify which features are systematically easier/harder to explain (e.g., by sparsity, activation frequency, layer, type) and build predictors to prioritize high-impact features for explanation.

- Formal foundations: Provide a theoretical framework for privileged access—conditions under which internal-state access enables superior explanations, identifiability of explanations, and guarantees (or impossibility results) for faithfulness.

- Simulator reliance: The simulator is trained on FineWeb with Neuronpedia labels; evaluate multiple simulators, quantify simulator bias/variance, and develop simulator-free evaluations (e.g., activation → token behavioral tests) to reduce circularity.

- Token/layer inference limits: Layer/token info was often recoverable from activations; systematically characterize limits (noise, obfuscation, mixed activations), and test whether explainer performance degrades when diagnostic metadata is withheld or corrupted.

- Intervention selection and coverage: Patching experiments use balanced sampling for changed/unchanged outcomes; measure sensitivity to sampling schemes and ensure coverage of rare but important intervention patterns.

- Compute and deployment costs: Activation hooking, projection, and inference with continuous-token insertion impose overhead; quantify runtime/memory costs, latency impacts, and feasibility in production settings, along with potential optimizations (e.g., low-rank adapters, compressed hooks).

- Beyond language: Extend introspective interpretability to vision and multimodal models; test whether privileged access similarly improves explanations for visual features, cross-modal alignments, and multimodal intervention outcomes.

- Ethical and governance implications: Investigate how to calibrate trust in self-explanations, detect unfaithful outputs, and incorporate introspective interpretability into audits, alignment evaluations, and deployment policies.

Glossary

- Activation alignment: The degree to which the internal activations of two models (or a model and a projection of another) are similar or aligned, often predictive of cross-model explanation quality. "Visually, they suggest that activation alignment is correlated with privileged access, in line with our findings above."

- Activation Differences (ΔACT): A representation formed by subtracting hidden activations between two matched inputs to isolate the effect of a specific change. "Activation Differences (ACT)."

- Activation patching: An intervention technique that replaces a model’s hidden activation at a specific location with one from a counterfactual run to test causal influence on outputs. "we perform activation patching by running on a counterfactual input "

- Attribution: Methods that assign responsibility or contribution of inputs or components to a model’s outputs. "work using attribution, feature visualization, and mechanistic interpretability techniques"

- Auto-interp: An automated interpretability procedure that generates natural-language descriptions of internal features. "(A) descriptions of features of the target model's hidden representations via an auto-interp procedure,"

- Chain-of-thought: Step-by-step natural language reasoning produced by models, often evaluated for faithfulness to internal computation. "reasoning models failed to produce faithful chains-of-thought"

- Circuit tracing: Techniques that map causal pathways through model components (layers, heads, neurons) by interventions or analysis. "We can answer questions of this form through activation patching and circuit tracing methods."

- Content Match: A metric assessing whether an explainer correctly predicts the new content of a model’s output after an intervention. "Content Match: Measures correctness of the second part of the explainer's prediction"

- CounterFact: A dataset of factual triples used to construct counterfactual prompts for intervention experiments. "We use the CounterFact dataset~\citep{meng2022locating}"

- Counterfactual input: An altered input designed to differ on a targeted factor for causal testing. "we perform activation patching by running on a counterfactual input "

- Cross-entropy loss: Standard optimization objective that encourages predicted explanation text to match supervision. "minimizing the cross-entropy loss on the explanation:"

- Exact Match: A strict metric that requires both the change/no-change decision and the predicted content to match the ground truth exactly. "Exact Match: Exact match accuracy between generated explanation and ground-truth explanation."

- Feature description: A natural-language label summarizing what inputs activate a specific internal direction or feature. "Feature Descriptions: What does a model-internal feature represent?"

- Feature visualization: Techniques for surfacing what features neurons or directions respond to, often via synthetic or corpus examples. "work using attribution, feature visualization, and mechanistic interpretability techniques"

- FineWeb: A large web-crawled corpus used for training or evaluating simulators and activations. "We train the simulator following~\citet{choi2024automatic} on FineWeb exemplars~\citep{penedo2024the} with Neuronpedia SAE labels."

- Instruction-tuning: Additional supervised fine-tuning to improve instruction-following behaviors, potentially changing internal representations. "has an additional instruction-tuning step"

- Introspective interpretability: Approaches where models leverage access to their internals to generate explanations of their own computation. "“introspective interpretability” techniques offer an avenue towards scalable understanding of model behavior."

- LM judge: A LLM used as an evaluator to score the similarity or quality of generated explanations against references. "we use an LM judge to assess the similarity of the predicted description to the gold description"

- LM simulator: A LLM prompted or trained to predict activations from textual feature descriptions, enabling automatic scoring. "a “simulator” LLM (LM simulator in \Cref{fig:methods_features})"

- Llama-Scope: A toolkit for extracting and analyzing sparse features (e.g., SAE dictionaries) from Llama models. "we use Llama-Scope~\citep{he2024llamascope} to obtain residual stream SAE features"

- LoRA: A parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that injects low-rank adapters into weight matrices. "we report results with both LoRA~\citep{hu2022lora} and full-parameter fine-tuning"

- Macro F1: Class-averaged F1 score that treats each class equally, used here for change/no-change classification. "We report the Macro F1 scores over the “changed” and “unchanged” classes."

- Mechanistic interpretability: The study of how model internals (circuits, representations) implement behaviors. "work using attribution, feature visualization, and mechanistic interpretability techniques"

- MMLU: A multi-task language understanding benchmark of multiple-choice questions across many subjects. "We use MMLU~\citep{hendryckstest2021}"

- Nearest-neighbor baseline: A retrieval method that labels a new feature by reusing the description of the most similar training feature. "we compare to a nearest-neighbor baseline"

- Neuronpedia: A community resource providing labels and descriptions for neurons and learned features. "Ground-truth explanations for each feature were obtained from Neuronpedia~\citep{neuronpedia}."

- Pearson correlation: A correlation coefficient used to compare true and simulated activation patterns. "the Pearson correlation between the model's true activations and its predicted activations"

- Polysemantic: Describes units or directions that represent multiple concepts simultaneously. "activations tend to be highly polysemantic"

- Privileged Access Hypothesis: The paper’s central claim that models explain themselves better than others can. "The Privileged Access Hypothesis"

- Projection layer: A learned linear mapping used to align features from a target model’s hidden size to an explainer’s hidden size. "the projection layer is pre-trained"

- Residual stream: The main vector pathway in a Transformer where layer outputs are added and passed onward. "residual stream representations "

- SAE (Sparse Auto-Encoder): A sparse representation learning method producing interpretable feature dictionaries from activations. "Sparse Auto-Encoder (SAEs) features"

- Self-explaining: A model describing its own internal computations or features. "we use the term “self-explaining” in this looser sense."

- SelfIE: A technique that patches features into a model and prompts it to describe the injected feature. "Following SelfIE~\citep{chen2024selfie}, we directly patch into the embedding layer"

- Simulator score: The evaluation metric based on correlation between true activations and activations predicted by the simulator given the explanation. "We also use simulator score, described in~\Cref{eq:simulator_correlation}"

- Sparse dictionary learning: Learning sparse bases (dictionaries) that decompose activations into interpretable features. "sparse dictionary learning approaches"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are actionable uses that can be deployed with current open‑weight LMs and standard MLOps stacks, given access to model internals and modest fine‑tuning budget.

- Self-explaining SDK for LLMOps (Software/Platform, Industry/Academia)

- What: A library/CLI to auto-generate faithful, human-readable descriptions of model features and predict outcomes of activation interventions and input ablations for a target LM.

- How: Wraps sparse autoencoders (SAEs) or neuron dictionaries, the paper’s simulator-based labeling, and “continuous-token” insertion to fine-tune an explainer that matches the target model; outputs explanations, simulator correlations, and confidence.

- Workflow: Train per-model explainer on tens of thousands of feature-label pairs; integrate into CI/CD to refresh explanations after model updates; expose a dashboard (e.g., integrated with Weights & Biases/MLflow) for browsing features and interventions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Open weights or first-party hosting; access to residual activations; ability to inject vectors and fine-tune an explainer; SAE dictionaries or equivalent; projection layers if hidden sizes differ.

- Debugging and regression testing of LMs (Software, Industry)

- What: Detect spurious, brittle, or shifted behaviors by tracking which features, layers, and tokens actually drive outputs across model versions or datasets.

- How: Use activation patching predictors to localize causally decisive layers/tokens; use input ablation predictors to quantify whether “hints” or prompts unduly sway answers.

- Workflow: Add “explanation checks” to A/B tests and pre-release evaluation; flag regressions when privileged-access explanations diverge or when sensitive features become predictive.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Comparable feature bases over time (e.g., stable SAEs or alignment via learned projections); standardized prompts and evaluation sets.

- Compliance-friendly explanation logging (Finance, Healthcare, Policy/Regulatory)

- What: Generate audit artifacts that specify which inputs/phrases influenced an answer and which internal features/layers were decisive.

- How: Use input ablation to produce has-changed flags and new-output predictions with causality summaries; attach “reason codes” that map tokens/features to decisions.

- Workflow: Store per-decision explanation objects with timestamps and metrics (LM-judge scores; simulator correlations); surface them in model cards and audit trails.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain review to avoid misinterpretation; recognition that explanations are approximations; regulators may require validation studies and guardrails against gaming.

- Prompt security and red-team triage (Software/Security, Industry)

- What: Identify whether injected strings, hints, or jailbreak patterns would actually change a model’s outputs.

- How: Use input ablation predictors to simulate the effect of prompt manipulations; rank prompts by influence magnitude and content change.

- Workflow: Integrate into red-team pipelines to prioritize high-influence adversarial prompts; use activation patching predictions to test which layers/tokens are attack surfaces.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Coverage limits for very long contexts and multi-turn flows; may require instruction-tuned explainers for chat models.

- Dataset curation and PII/bias scanning (Data Platforms, Policy/Trust & Safety)

- What: Use feature descriptions to detect PII-triggering or protected-attribute proxies (e.g., names, dialect markers) that models leverage.

- How: Scan corpora with feature descriptions; remove or mask segments that activate sensitive features; repeat scans post-augmentation.

- Workflow: Add “feature-trigger scanning” to data ingestion; report pre/post activation-rate changes in data governance dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality sensitive-feature taxonomies; noisy labels in ground truth can propagate; requires human-in-the-loop review.

- Targeted model editing and guardrails (AI Safety/Platform, Industry/Academia)

- What: Identify minimal components to alter for safe edits (e.g., reduce reliance on a spurious feature).

- How: Use activation patching predictions to propose candidate layers/tokens for editing or routing; monitor downstream change with the explainer.

- Workflow: Combine with editing methods (e.g., ROME/LoRA patches) and re-run explainer-based causal checks as validation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Edits generalize only locally; risk of side effects; explainer quality depends on activation alignment.

- Low-cost interpretability dataset generation (Academia/Research, Software)

- What: Use self-explainers to cheaply produce large, reasonably faithful corpora of feature labels, ablation outcomes, and causal narratives for new models.

- How: Train a matched explainer with small supervision; scale label generation with the paper’s data-efficiency; spot-check with LM-judge/human audits.

- Workflow: Release “explanation packs” alongside open models (SAE dictionaries + natural-language descriptions + simulator correlations).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality gated by initial supervision and simulator fidelity; cross-model transfer weaker without alignment.

- Pedagogical tools for teaching ML concepts (Education, Daily Life/EdTech)

- What: Interactive lessons that reveal which tokens/features drive specific outputs and how interventions change predictions.

- How: Layer-by-layer visualizations tied to natural-language descriptions and predicted outcomes of patches/ablations.

- Workflow: Classroom labs and online micro-tutors that let students manipulate inputs and see faithful internal effects.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Best with open models; simplified UIs to avoid overconfidence in “explanations as truth.”

Long-Term Applications

These uses need further research, scaling, standardization, or secure deployment pathways.

- Certifiable transparency for regulation and procurement (Policy/Governance across sectors)

- What: Standardized “introspection APIs” and benchmarks that auditors can run to verify which inputs/features drive model outputs in high-risk systems (EU AI Act, healthcare/finance regulation).

- How: Sector-specific protocols, calibration metrics (e.g., simulator correlation thresholds), and shadow evaluations.

- Dependencies: Third-party verifiability for closed models (secure enclaves/attested runs), robust anti-gaming tests, and domain validation.

- Self-monitoring, self-correcting AI agents (Software/Safety, Robotics)

- What: Agents that use introspective signals to detect spurious reasoning, trigger replanning, or request more context.

- How: Train with an auxiliary “faithful explanation” loss and runtime introspection hooks; penalize reliance on flagged features.

- Dependencies: Adversarial robustness of explanations; avoiding learned deception; compute overhead acceptable in latency-sensitive settings.

- High-stakes decision support with faithful reason codes (Healthcare, Finance, Public Sector)

- What: Clinicians/underwriters receive causally grounded reason codes rather than generic rationales; enables contestability and appeals.

- How: Model families pre-certified for introspection quality; per-domain feature ontologies; standardized reason-code formats.

- Dependencies: Prospective clinical/field trials; bias, privacy, and safety reviews; patient/consumer communication standards.

- Cross-model interpretability translation layers (Software/Standards)

- What: Projection/alignment layers that let one family (e.g., Qwen) reliably explain another (e.g., Llama) with minimal loss.

- How: Pretrain projection modules on paired activations; publish per-layer alignment packs as part of model releases.

- Dependencies: IP/weight access; stability across updates; evidence that alignment preserves causal semantics, not just correlation.

- Mechanistic oversight and training-time alignment (AI Safety/Research)

- What: Use privileged-access objectives during pretraining/finetuning to shape internal representations toward monosemantic, auditable features.

- How: Jointly optimize next-token loss with explanation faithfulness and patching-predictability losses; select architectures that facilitate introspection.

- Dependencies: Scalability to frontier models; preventing spec gaming; measuring true causal faithfulness vs. verbal mimicry.

- Privacy and data lineage auditing (Policy/Trust & Safety)

- What: Detect if models rely on features suggestive of training-data leakage or PII; generate “use-of-sensitive-feature” attestations.

- How: Periodic scans using feature descriptions; counterfactual ablations for suspected PII triggers; redaction pipelines.

- Dependencies: Strong PII/proxy libraries; differential privacy compatibility; legal acceptability of probabilistic audits.

- Robotics and control introspection (Robotics/Energy/Industrial)

- What: Extend to policy networks to explain which sensor inputs and internal features trigger actions, for safety certification in autonomous systems and grid control.

- How: Generalize activation/ablation methods to continuous control; integrate with simulator environments for ground truth.

- Dependencies: Domain gap from LMs to control networks; real-time constraints; causal evaluation beyond language.

- End-to-end “Explainability OS” for enterprises (Software/Platform)

- What: Production suite combining SAE management, explainer training, dashboards, policy checks, and red-team tooling with APIs for product teams.

- How: Multi-model support, versioned explanation stores, policy rule engines (e.g., no-sensitive-feature dependency), and exportable reports.

- Dependencies: Vendor-neutral standards; reliability SLAs for explanations; secure handling of internal activations.

Notes on Feasibility, Risks, and Assumptions

- Access: Most immediate applications assume open-weight or first‑party models where internal activations can be read and an explainer can be fine‑tuned. API‑only closed models will need attested introspection endpoints or on-prem agreements.

- Label quality: Ground-truth labels from SAEs and simulators are noisy; explanations are “best-effort” approximations. Human spot-checks and multiple metrics (e.g., simulator correlation + task impact) should gate deployment.

- Alignment matters: Explainers work best when closely matched to their targets (architecture/training); projection/alignment layers mitigate but don’t eliminate gaps.

- Distribution shift: Explanations learned on one domain may drift; include periodic recalibration and shift detection.

- Gaming risk: Models could learn to output plausible but unfaithful explanations if trained naively; include causal evaluations (interventions) and anti-gaming tests.

- Overhead: Introspection adds compute (feature extraction, interventions, simulation); budget for offline batch analysis or selective runtime checks.

- Communication: In high-stakes contexts, present explanations as decision aids with uncertainty, not as proofs; ensure user training and documentation.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.