- The paper introduces a framework for quantifying structural uncertainty in PIML by analyzing rank conditions to ensure uniqueness of inferred coefficient functions.

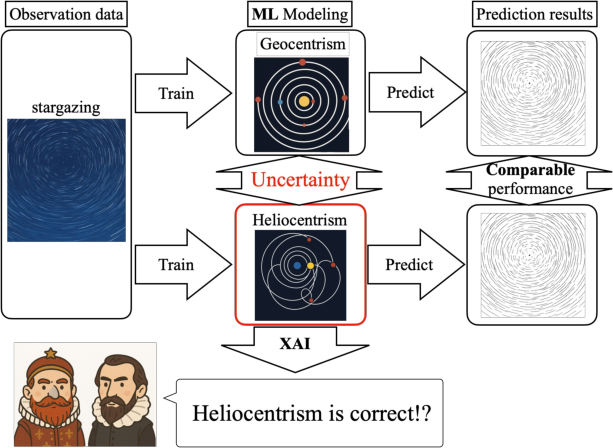

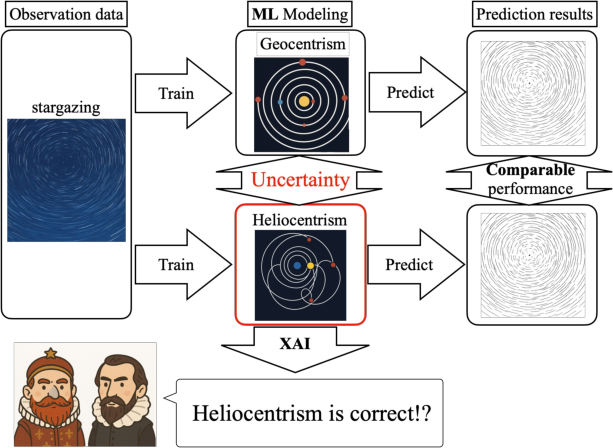

- It demonstrates that high predictive accuracy can still lead to unphysical solutions, highlighting risks in data-driven scientific inference.

- The study outlines practical procedures to incorporate physical constraints, such as symmetry and conservation laws, for more interpretable modeling.

Introduction: The Central Challenge in Data-Driven Scientific Discovery

The integration of machine learning methods, particularly deep neural networks, with physical modeling has catalyzed recent advances in scientific discovery, especially within the context of physics-informed machine learning (PIML). PIML, and closely related methods such as Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Hamiltonian Neural Networks (HNNs), enable the solution of inverse problems in which unknown coefficient functions or operators in partial differential equations (PDEs) are inferred from observational data. However, the primary criterion for model selection and evaluation in PIML is often prediction accuracy, a standard that may fail to ensure that the inferred models reflect underlying physical truths.

This paper rigorously addresses the previously underexplored domain of structural uncertainty in PIML-driven inverse problems—uncertainty that arises due to inherent indeterminacies in the mapping from data to model, even without noise or limited data. This form of uncertainty stands apart from model-form and data uncertainties. The authors introduce an analytic framework to evaluate and quantify structural uncertainty in the estimation of coefficient functions, apply it to a kinetic wave equation scenario relevant for plasma physics, and argue that appropriate physical or geometric constraints are required to guarantee uniqueness and physical interpretability in solutions.

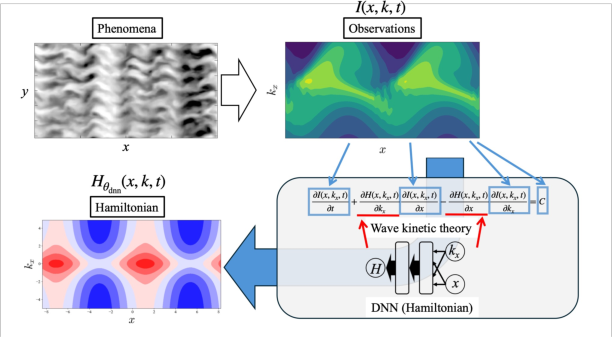

Figure 1: Risks associated with naive scientific inference using machine learning under uncertainty, potentially resulting in physically incorrect conclusions.

A central theoretical advance of the paper is the explicit categorization and delineation of three distinct sources of uncertainty in data-driven modeling:

- Structural Uncertainty: Even with infinite noiseless data, multiple mathematically valid models may explain the observations equally well given the same data and model class, owing to ambiguities intrinsic to the PDE or its parameterization.

- Model-Form Uncertainty: Arises when the true physical law resides outside the model class being fit, hence improper or incomplete modeling introduces uncertainty.

- Data Uncertainty: Results from limited, noisy, or otherwise imperfect data, and can be treated statistically via Bayesian inference or posterior analysis.

The analysis demonstrates that structural uncertainty, being intrinsic to the mathematical structure of the inverse problem, cannot be alleviated by simply acquiring more data or reducing measurement noise. Instead, additional physical constraints—such as symmetry or geometric properties—are necessary to achieve unique identification of coefficient functions. The paper also cautions against overreliance on predictive performance for model selection, as it may prefer non-physical solutions in the presence of structural indeterminacy.

The core theoretical contribution is a general framework for quantifying structural uncertainty in coefficient function estimation from PDE-based constraints. The methodology involves discretizing the domain and assessing the rank of the linear system induced by the PDEs at finely discretized grid points.

Main theorem: If the matrix M, composed of discretized PDE constraints on the coefficient function a(x), has full rank (rank(M)=∣A≤m∣N), then a(x) is uniquely determined up to a polynomial of degree at most k−1, where k is related to the order of partial derivatives present in the equation. If the rank condition is not met, the solution is fundamentally non-unique.

This result is illustrated through canonical examples:

- Hamiltonian systems: Under sufficient data and observations, the Hamiltonian function H(q,p) is determined up to an additive constant, reflecting the well-known physical gauge invariance in energy.

- Lagrangian systems: Absent certain physical constraints (e.g., definition of generalized momentum), the Lagrangian function cannot be uniquely identified due to underdetermined equations.

Practical Framework for PIML with Uncertainty Quantification

The authors advocate for a three-step procedure prior to neural network training for scientific inference:

- Uncertainty Analysis: Analyze the PDE structure and evaluate the rank of the corresponding matrix to predict whether the coefficient function can be uniquely recovered.

- Constraint Augmentation: If indeterminacy is found, introduce additional physical constraints (such as symmetries or conservation laws) directly as regularization terms or architectural features in the loss function.

- Constraint Sensitivity Analysis: Rather than relying solely on validation loss or prediction accuracy, inspect how estimated functions vary with the strength of imposed constraints, thereby allowing practitioners (e.g., physicists) to interpret subtle signatures in the estimation as potential physical insights.

Case Study: Hamiltonian Estimation in Turbulent Plasma Systems

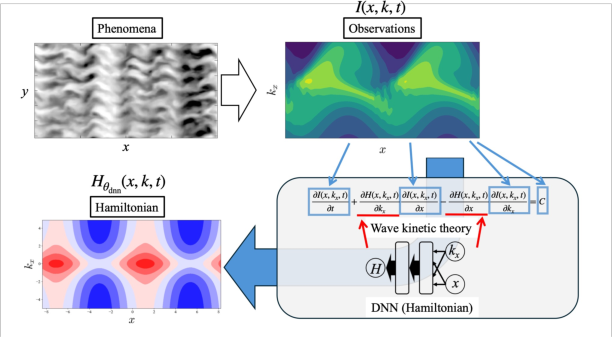

The framework is demonstrated on the problem of reconstructing a spatially dependent Hamiltonian from numerical solutions of a wave kinetic equation relevant in fusion plasma turbulence modeling.

Figure 2: Schematic of data-driven Hamiltonian estimation for wave kinetic equations using PIML.

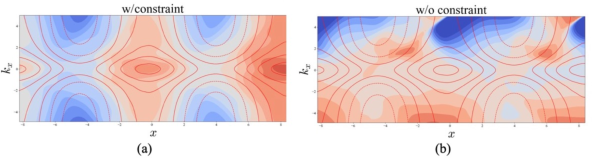

The original system is structurally underdetermined: attempting to fit Hamiltonian derivatives (Hx,Hkx) without further physical assumptions leads to an ill-posed problem. The authors impose a physically motivated symmetry—line symmetry of the Hamiltonian with respect to kx=0—reflecting the known absence of directional bias. Post-constraint, the rank condition for unique identifiability is satisfied.

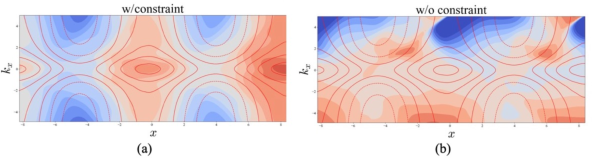

Algorithmically, the DNN is trained using a composite loss function containing both the PDE residual and a term enforcing the symmetry constraint. Notably, the paper finds that the unconstrained model achieves lower validation loss (better predictive accuracy) but learns unphysical Hamiltonians, while the constrained model, although sacrificing some prediction error, recovers a Hamiltonian that matches the ground-truth both visually and quantitatively (higher cosine similarity with the true Hamiltonian).

Figure 3: Estimated Hamiltonian functions—(a) with symmetry constraints, recovering the true Hamiltonian; (b) without constraints yields non-physical solutions despite low predictive loss.

Implications for Scientific AI and Future Directions

This work provides a rigorous approach to assessing identifiability and risk of physically incorrect inference in science applications of AI. The critical insight—predictive accuracy is neither necessary nor sufficient for physical interpretability—challenges prevalent practices in scientific deep learning.

The theoretical framework is currently restricted to PDEs linear in the unknown coefficients, but the authors identify extensions to nonlinear PDEs, potentially via singular learning theory and loss landscape analysis, as an important area for method development.

Furthermore, empirical analyses in the supplemental material demonstrate that the use of DNNs can partially mitigate practical issues such as path-dependent integral inconsistencies and numerical errors due to finite discrete data, supplementing the theoretically idealized grid-based framework for uncertainty evaluation.

Conclusion

This paper advances the field by formalizing structural uncertainty in physics-informed inverse problems, proposing a practical framework for uncertainty evaluation and constraint-driven model selection, and empirically validating the approach in turbulent plasma modeling. The demonstration that unconstrained yet highly predictive models can yield physically invalid solutions underscores the necessity for interpretability, constraint integration, and careful uncertainty quantification in scientific AI. The methods and cautions articulated here are pertinent to future developments in the application of machine learning to scientific model discovery and suggest promising directions for the systematic analysis of identifiability in more general and nonlinear settings.