Thor: Towards Human-Level Whole-Body Reactions for Intense Contact-Rich Environments

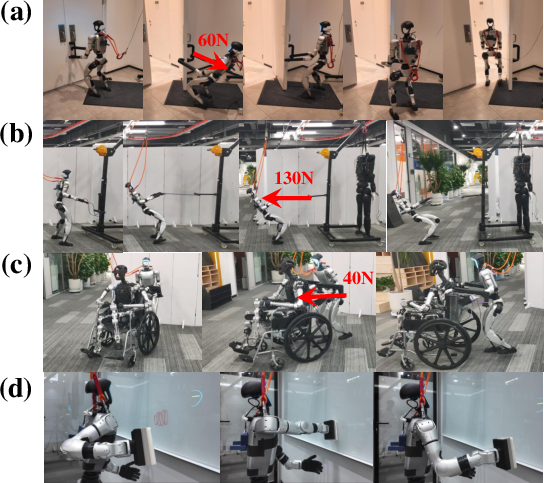

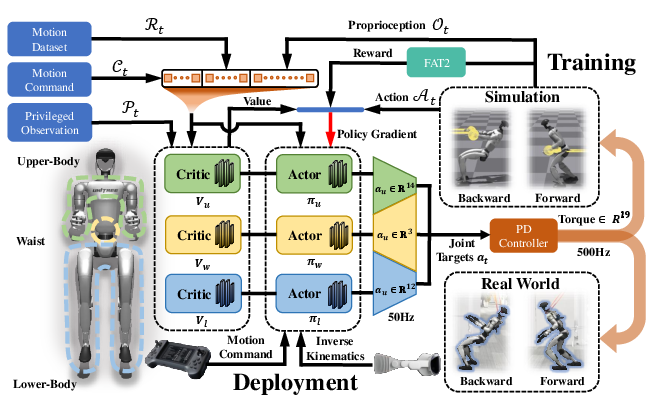

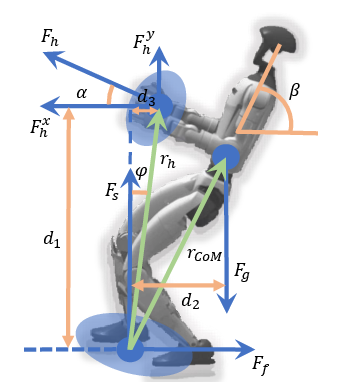

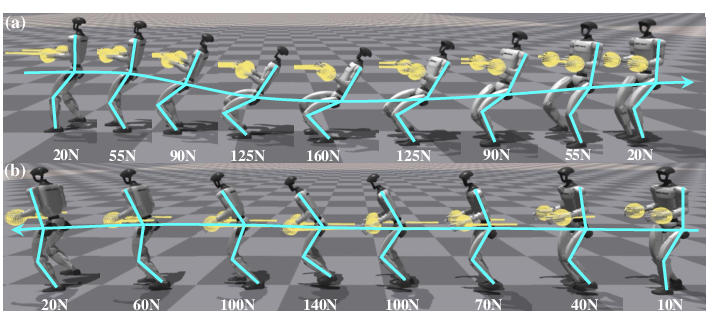

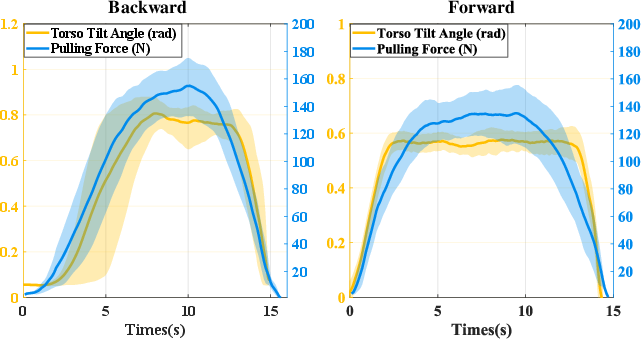

Abstract: Humanoids hold great potential for service, industrial, and rescue applications, in which robots must sustain whole-body stability while performing intense, contact-rich interactions with the environment. However, enabling humanoids to generate human-like, adaptive responses under such conditions remains a major challenge. To address this, we propose Thor, a humanoid framework for human-level whole-body reactions in contact-rich environments. Based on the robot's force analysis, we design a force-adaptive torso-tilt (FAT2) reward function to encourage humanoids to exhibit human-like responses during force-interaction tasks. To mitigate the high-dimensional challenges of humanoid control, Thor introduces a reinforcement learning architecture that decouples the upper body, waist, and lower body. Each component shares global observations of the whole body and jointly updates its parameters. Finally, we deploy Thor on the Unitree G1, and it substantially outperforms baselines in force-interaction tasks. Specifically, the robot achieves a peak pulling force of 167.7 N (approximately 48% of the G1's body weight) when moving backward and 145.5 N when moving forward, representing improvements of 68.9% and 74.7%, respectively, compared with the best-performing baseline. Moreover, Thor is capable of pulling a loaded rack (130 N) and opening a fire door with one hand (60 N). These results highlight Thor's effectiveness in enhancing humanoid force-interaction capabilities.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces Thor, a new way to control humanoid robots so they can safely and powerfully interact with the world—like pulling heavy objects, opening tough doors, or pushing wheelchairs—without falling over. The big idea is to help robots react more like humans do in “contact-rich” situations by leaning their bodies in smart ways and coordinating all their limbs.

Key Objectives

The paper focuses on three simple questions:

- Does teaching a robot to lean its torso like a human help it pull or push harder while staying balanced?

- How much better is Thor compared to other robot control methods?

- Which matters more for performance: the special “leaning” reward or the new three-part (upper body, waist, lower body) control design?

How They Did It (Methods)

The main ideas, in simple terms

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): The robot learns by trial and error in a simulator. If it does well (moves smoothly, stays balanced, pulls harder), it gets “rewards” and adjusts its behavior.

- Three “brains” working together: Instead of one big controller, Thor splits the robot’s control into three parts:

- Lower body: handles walking and foot stability.

- Waist: acts like a force bridge, passing ground push/pull to the arms.

- Upper body: tracks arm and torso motions, like reaching or pulling.

- These three parts share what they see from the whole robot, learn together, and combine their outputs to control all joints.

- FAT2 reward (Force-Adaptive Torso-Tilt): This is a special reward that encourages the robot to lean its body, just like people naturally lean back when pulling or lean forward when pushing. Leaning changes where your weight is, which helps you apply more force without slipping or tipping.

- Everyday example: When you open a heavy fire door, you don’t just “pull harder”—you step back and lean your torso to balance the force.

- Training strategy:

- Curriculum learning: Start with easier conditions (smaller forces), then gradually move to harder ones (bigger forces and disturbances).

- Domain randomization: Mix up the directions and sizes of the forces during training so the robot can handle many real-world surprises.

What “balance” means here

The paper uses a standard idea from robotics called the ZMP (Zero Moment Point). Think of it like this: to avoid tipping, the robot needs to keep the “effective pressure and torque” within the area under its feet. Leaning adjusts where the robot’s weight and forces go so it stays balanced while pulling hard.

From simulator to real robot

After training in simulation, the team tested Thor on a real Unitree G1 humanoid. The learned control runs fast enough on the robot, and a simple torque controller turns the “desired joint positions” into motor commands.

Main Findings

- Stronger pulling with better balance:

- Backward pulling with two hands: 167.7 ± 2.4 N (about 48% of the robot’s body weight), a 68.9% improvement over the best baseline.

- Forward pulling: 145.5 ± 2.0 N, a 74.7% improvement over the best baseline.

- Real-world tasks Thor could do:

- Open a heavy fire door with one hand (about 60 N needed).

- Pull a loaded rack (about 130 N).

- Push and turn a wheelchair carrying a 60 kg load.

- Wipe a whiteboard while keeping stable contact.

- What helps most:

- The FAT2 “lean like a human” reward accounted for most of the performance gain (about 80–90% of Thor’s improvement).

- The three-part control design (upper body, waist, lower body) reduced weird waist motions and made learning more stable, which helped reach the highest forces safely.

Why It Matters

This research makes humanoid robots more capable in everyday, messy situations where they have to push, pull, and hold things firmly—like helping in factories, homes, or rescue missions. Instead of relying on super-precise models, Thor learns from experience and uses human-inspired strategies (leaning and whole-body coordination) to stay balanced while applying strong forces. That means robots can do more useful work and handle tougher environments with fewer hand-crafted rules.

Looking ahead

The authors plan to reduce the need for careful tuning by learning from human demonstrations (e.g., videos), which could make training faster and more reliable. This would push humanoid robots even closer to human-level reactions in the real world.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, concise list of knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions left unresolved by the paper. Each point is intended to be concrete and actionable for future research.

- Lack of formal stability guarantees beyond quasi-static assumptions: no proof or empirical verification of balance when CoM lies outside the foot support polygon under large external forces; COP/ZMP measurements and foot slip detection are absent.

- FAT2 derivation relies on simplifying assumptions (e.g., neglecting d3, fixed βmax=0.9 rad, small sinφ): no sensitivity analysis across postures, anthropometrics, or interaction geometries; no validation of the reward’s correctness under varied kinematics.

- External force sensing is not available at deployment; the policy infers interaction forces implicitly from torso signals without an explicit estimator. Accuracy, latency, and robustness of this implicit inference are unquantified.

- Privileged-information reliance (EE forces in the critic) is not ablated: performance without privileged inputs during training or with noisy/inaccurate privileged signals is unknown.

- Domain randomization is limited to force direction/magnitude; it excludes uncertainties in mass/inertia, actuator dynamics, time delays, sensor noise, contact compliance, and friction variability.

- PD controller gains and torque limits are unspecified; the impact of low-level controller parameterization on stability, performance, and sim-to-real transfer is not analyzed.

- No measurement or management of motor saturation, thermal limits, or energy/power consumption during high-force tasks; torque regularization effects are not linked to hardware constraints.

- Inference runs at 50 Hz, yet required control bandwidth for intense contact tasks is not studied; the effect of actuation/communication latency and lower control rates on stability is unknown.

- Evaluation focuses on peak pulling force over 10 seconds; sustained force tracking, force ramp-up/down profiles, compliance under disturbances, and task success rates across trials/environments are missing.

- ZMP/COP and ground reaction/friction measurements are not reported; assertions about leveraging body weight and friction are not supported by contact-wrench data or slip metrics.

- Real-world tests use shoe covers to increase friction without quantifying the friction coefficient; performance dependence on friction level is not characterized (e.g., force vs. μ curves).

- Task diversity is limited (planar pulling/pushing/wiping); vertical tasks (lifting, pulling up/down), asymmetric bimanual interactions, yaw-torque-rich manipulation, and multi-contact strategies (e.g., bracing against the environment) are unexplored.

- Terrain generalization (slopes, stairs, uneven/compliant surfaces) is untested; robustness to terrain-induced contact changes and foot placements is unknown.

- Perception-free control: upper-body actions are driven by VR or motion datasets; autonomous perception and planning for contact-rich manipulation (e.g., door handle detection, grasp planning) are not integrated.

- Manual hyperparameter tuning is acknowledged; there is no systematic sensitivity analysis, auto-tuning, or meta-learning to reduce dependence on entropy coefficients, learning rates, and reward scales.

- Decoupled architecture effects on coordination are underexplored: no analysis of inter-agent communication, stability modes (e.g., waist roll anomalies), or comparison to alternative decompositions (e.g., hierarchical controllers, leg-wise decoupling).

- Curriculum learning details are minimal; the method’s sample efficiency, convergence variability across seeds, and transferability of curricula to new tasks/domains are not evaluated.

- Generalization to different humanoid platforms (morphologies, DoF distributions, mass properties) is untested; portability and required retuning/calibration steps remain unclear.

- Safety under human-robot interaction (fallback strategies, tilt limits, recovery from near-fall states) is not addressed; risk assessment and safety constraints are missing.

- No explicit constraints or monitoring for foot-ground friction model (e.g., maximum static friction); the policy’s behavior under low-friction conditions (without shoe covers) is uncertain.

- Reward design trade-offs are not dissected: how FAT2 interacts with locomotion and tracking rewards, potential to induce excessive/unsafe tilt, and constraint mechanisms to bound posture are not studied.

- Reproducibility is limited: code, exact reward weights, controller gains, training seeds, curriculum schedules, and deployment stack details are not provided; results may be difficult to replicate.

- Open question: can integrating lightweight force/tactile sensing (hands/wrists/feet) improve performance and reduce reliance on privileged info/implicit estimation?

- Open question: how does the approach handle time-varying, impulsive, or adversarial external forces (e.g., tug-of-war opponent) while maintaining balance and task performance?

Glossary

- Ablation study: An experiment where specific components of a system are removed or isolated to assess their contribution. "To answer Q3, we conducted ablation studies"

- Actor-Critic network: A reinforcement learning architecture with separate policy (actor) and value (critic) components. "with each component equipped with its own Actor-Critic network structure."

- AMASS dataset: A large collection of human motion capture data used for learning and imitation. "upper-body motions randomly sampled from the AMASS \cite{AMASS} dataset during training."

- Biomechanics: The study of mechanical principles applied to biological systems, such as human movement. "Inspired by expert knowledge from human biomechanics \cite{Analysis-of-Tug}, \cite{Low-Back-Biomechanics}, we design..."

- Center of Mass (CoM): The point where the total mass of a body can be considered to be concentrated. "the gravitational force acting at the center of mass (CoM)."

- Critic network: The value-estimation component in actor-critic RL that evaluates states or state-action pairs. "The Critic network incorporates privileged information inputs, including the magnitude and direction of forces experienced by the EEs."

- Curriculum learning: A training strategy that gradually increases task difficulty to improve learning efficiency. "we implemented a two-stage curriculum learning approach based on task difficulty."

- Decoupled network architecture: A control design that splits a high-dimensional system into coordinated sub-policies. "we design a novel decoupled network architecture for the upper body, waist, and lower body"

- Domain randomization: Randomly varying simulation parameters to improve robustness and transfer to the real world. "we incorporated domain randomization in both the direction and magnitude of force disturbances applied to the humanoid’s end-effectors (EEs)"

- End-effector (EE): The terminal part of a robot that interacts with the environment (e.g., hands). "end-effectors (EEs)"

- End-to-end policy: A single policy that maps raw observations directly to actions without modular decomposition. "achieving an end-to-end policy for legged manipulator control."

- Force-adaptive torso-tilt (FAT2): A reward mechanism that encourages adaptive torso inclination to increase interaction forces while maintaining balance. "we design a force-adaptive torso-tilt (FAT2) reward function"

- Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE): An estimator that balances bias and variance in computing advantages for policy updates. "compute their respective Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) for parameter updates."

- Impedance control: A control approach that regulates dynamic relations between force and motion, often modeled as mass-spring-damper. "Inspired by impedance control, Facet \cite{FACET} employs RL to train a control policy that simulates a virtual mass-spring-damper system, exhibiting controllable compliance."

- Inverse kinematics (IK): The process of computing joint angles that achieve a desired end-effector pose. "utilizes inverse kinematics (IK) and motion retargeting for precise manipulation."

- Isaac Gym: A GPU-accelerated physics simulation platform for large-scale robotics RL training. "We conducted the RL policy training of Thor in the simulatior Isaac Gym."

- Linear inverted pendulum (3D): A simplified dynamic model of bipedal balance where the mass is above a pivot point, extended to three dimensions. "instability, akin to a 3D linear inverted pendulum"

- Loco-manipulation: Tasks that require simultaneous locomotion and manipulation. "Falcon \cite{Falcon} enables humanoids to perform forceful loco-manipulation tasks"

- Markov Decision Process (MDP): A formal framework for sequential decision-making involving states, actions, and transitions. "can be modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP)."

- Multi-agent RL: Reinforcement learning involving multiple interacting policies or agents. "Inspired by multi-agent RL \cite{Learning_Advanced_Locomotion}, \cite{Multi-agent_survey}"

- PD controller: A proportional-derivative controller that computes torques from position and velocity errors. "processed through a PD controller to generate the output joint torques."

- Policy distillation: The process of merging or transferring multiple policies into a single model. "HOVER \cite{2025ICRA-HOVER} employs a multi-modal policy distillation framework that integrates various control modes into a unified policy."

- Privileged information: Training-only inputs not available at deployment, used to accelerate learning. "The Critic network incorporates privileged information inputs, including the magnitude and direction of forces experienced by the EEs."

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): An on-policy RL algorithm that uses a clipped objective to stabilize updates. "but each maintains separate network parameters that are updated using the PPO algorithm \cite{PPO}."

- Quadratic programming: Optimization of a quadratic objective subject to linear constraints, often used in control. "feedforward torque generated through quadratic programming."

- Quasi-static condition: An assumption of negligible accelerations where dynamics can be approximated by static equilibrium. "we consider a quasi-static condition"

- Reinforcement learning (RL): Learning control policies via trial-and-error guided by rewards. "Reinforcement learning (RL) methods \cite{Falcon}, \cite{2024ICRA-Sim-to-Real}, \cite{2024ICRA-Learning_Force_Contro}, \cite{2024CoRL-Human_Plus}, \cite{2025ICRA-Mobile-TeleVision}, which learn from experience"

- Sim-to-real gap: The performance discrepancy between simulated training and real-world deployment. "To address the potential sim-to-real gap, we incorporated domain randomization"

- Support polygon: The area enclosed by contact points (e.g., feet) within which the ZMP must lie for balance. "the humanoid’s CoM projection lies entirely outside the support polygon defined by its feet"

- Teacher–student architecture: A training paradigm where a teacher policy guides a student to learn desired behaviors. "Twist \cite{Twist} and Clone \cite{Clone} adopt a teacher–student architecture"

- Torque regularization: A penalty in the objective that discourages excessive actuator commands. "where represents torque regularization, which serves to prevent excessive output from specific components and to coordinate overall energy consumption"

- Unitree G1: A commercial humanoid robot platform used for experiments. "Finally, we deploy Thor on the Unitree G1, and it substantially outperforms baselines"

- Whole-body control (WBC): Coordinated control across all joints to achieve combined locomotion and manipulation goals. "we propose a novel whole-body control (WBC) framework for humanoids, named Thor."

- Zero Moment Point (ZMP) criterion: A balance condition requiring the net moment at the support point to be zero so the ZMP remains inside the support polygon. "The theoretical foundation of our method is established on the Zero Moment Point (ZMP) criterion with external force"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable use cases that directly leverage Thor’s demonstrated capabilities (FAT2 reward, decoupled upper–waist–lower policy, sim-to-real domain randomization, VR-teleop upper body, real robot validation on Unitree G1).

- Opening heavy fire doors with one hand (Facilities, Safety)

- Tools/products/workflows: Thor policy on a G1-class humanoid; simple door-hook end-effector; VR teleoperation for arm IK; RL lower body with FAT2 handles whole-body tilt and balance while pulling ≈60 N; PD torque control (500 Hz) with 50 Hz policy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Flat floors with adequate friction (may require friction-enhancing shoe covers); controlled environment and safety perimeter; operator-in-the-loop; reliable comms; heavy-lever/handle geometries accessible to the end-effector.

- Pulling and positioning loaded carts/racks up to ≈130 N (Logistics, Manufacturing)

- Tools/products/workflows: Handle adapter for standard carts; “force-interaction skill pack” deploying Thor’s policy to maintain stability under horizontal loads; site workflow: scheduled moves in corridors and warehouses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Smooth, high-friction floors; predictable routes; obstacles sparse; mechanical interfaces (handles) compatible with end-effector; worksite safety procedures.

- Wheelchair assistance and maneuvering (Healthcare, Assistive Services)

- Tools/products/workflows: Grip fixture on wheelchair handles; low-speed operation; teleop-guided upper body with autonomous force-adaptive locomotion; force thresholds and speed governors for patient safety.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Human supervision and institutional approval; non-patient transport or empty chair in early pilots; compliance with hospital safety policies; flat floors and adequate traction.

- Pressing/wiping tasks (whiteboards, panels) with stable force (Facilities, Education)

- Tools/products/workflows: Simple cleaning/wiping tool attachment; IK-based arm motion with Thor stabilizing the body under contact forces; repeatable facility maintenance routines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Known target surfaces and required contact forces; calibrated IK and end-effector; light-to-moderate interaction forces; slip-resistant flooring.

- Co-manipulation support for moving furniture or fixtures in controlled spaces (Service, Facilities)

- Tools/products/workflows: Human–robot protocol for synchronized pushing/pulling; robot maintains whole-body posture using FAT2 while a human adjusts object trajectory; voice/gesture cues or basic teleop.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Trained staff; shared load under 130 N regime; predictable partner behavior; clear communication; safety stop mechanisms.

- Lab and classroom benchmarking for forceful whole-body interaction (Academia, Standards)

- Tools/products/workflows: Reproduce the paper’s dynamometer-based protocols to measure peak forces across directions and gaits; ablation studies using Thor1 (FAT2 only) vs Thor2 (decoupled only); curriculum + domain randomization training recipe in Isaac Gym.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to G1-class humanoids or similar torque-controlled platforms; GPU (e.g., RTX 4090) for ~6–7 hours of training per stage; AMASS dataset for upper-body motion sampling; safety-compliant lab setup.

- Drop-in software module for high-frequency whole-body control (Software, Robotics)

- Tools/products/workflows: Integrate Thor’s decoupled actor–critic architecture and PD torque backend as a ROS/RTOS library; “FAT2 reward plugin” for training new force-interaction skills on different morphologies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: On-board compute can sustain ~50 Hz policy and 500 Hz torque loops; accurate state estimation; similar DoF layout or adapted mapping; licensing for simulation assets (Isaac Gym).

- Telepresence with autonomy assistance for stuck levers, tight drawers, and heavy handles (Industrial R&D, Education)

- Tools/products/workflows: VR teleoperation for precise hand pose; Thor stabilizes and amplifies contact forces via adaptive torso tilt; operator executes short-duration high-force maneuvers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Operator training; low-latency control link; known lever/handle geometry; friction and floor conditions suitable for safe whole-body leaning.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require additional research, scaling, sensing, and regulatory or product development beyond the current demonstrations (e.g., autonomy, robustness to varied terrains, or broader safety certification).

- Firefighting and disaster response: hose pulling, debris removal, forced-entry door opening, casualty dragging (Public Safety, Rescue)

- Tools/products/workflows: Ruggedized humanoid with weather/heat protection; force-torque sensors in wrists; autonomous perception under smoke/dust; task-level planning integrated with Thor-like whole-body control.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Certification for hazardous operations; extreme friction variability; uneven or debris-laden terrain; communications constraints; robust power supply.

- Patient handling and transfer assistance (Healthcare)

- Tools/products/workflows: Compliant, force-sensing arms; perception for human pose and intent; safety-rated control with strict force/pressure limits; workflow integration with nurses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Medical device regulatory approval (e.g., FDA/CE); multi-layer redundancy and fail-safes; human factors validation; extensive clinical trials.

- Autonomous hospital/warehouse porter: multi-door navigation, elevator use, route planning with forceful door handling (Healthcare, Logistics)

- Tools/products/workflows: Building systems integration (elevators, badge-access doors); semantic mapping; multi-modal perception; behavior trees combining Thor’s WBC with high-level autonomy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Building code alignment; strong reliability across floor types and slopes; persistent autonomy in crowded spaces; maintenance and fleet management.

- Industrial maintenance: operating large valves, latches, dampers, and spring-loaded mechanisms (Energy, Process Industries, Utilities)

- Tools/products/workflows: Specialized end-effectors (valve keys, torque adapters); perception of mechanism states; task libraries with force thresholds and FAT2-enhanced postures; safety zoning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Explosion-proof or high-EMI environments; outdoor/weather robustness; higher force/torque than 130–170 N envelope; integration with lock-out/tag-out procedures.

- Construction and facility retrofit: moving heavy panels, temporarily bracing elements, forceful fastening/unfastening (Construction)

- Tools/products/workflows: Tool ecosystem (drivers, clamps); coordinated multi-robot or human–robot teams; terrain-aware whole-body control with FAT2-like posture adaptation on uneven ground.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Uneven terrain and tripping hazards; variable friction; detailed safety planning; higher power and endurance; operator and site regulation compliance.

- Domestic assistance for aging-in-place: heavy door opening, moving appliances, handling stuck fixtures (Consumer Robotics, Elder Care)

- Tools/products/workflows: Home-grade, cost-reduced humanoid; intuitive supervision (voice/AR); safe compliance in cluttered spaces; household tool set.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliability and affordability; strong safety certification for close human contact; robust operation on rugs/low-friction floors; user acceptance.

- Standardization and policy for contact-rich humanoid operations (Policy, Standards)

- Tools/products/workflows: New standards for measuring interactive forces and ZMP-with-external-force stability; building guidelines for robot-accessible handles and thresholds; procurement specs for robotic door hardware.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Engagement with ISO/IEC/ASTM; multi-stakeholder consensus; pilot programs in public buildings and hospitals; liability and insurance frameworks.

- Avatar robotics in hazardous environments (Nuclear, Offshore, Space)

- Tools/products/workflows: Teleop with semi-autonomous stabilization (FAT2-style posture control); radiation/pressure/thermal hardening; remote handling of jammed valves or tight couplings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Harsh environment survivability; intermittent communications; higher peak forces and endurance; extensive operator training.

- Cross-domain adoption of FAT2 principles in exoskeletons and prosthetics to reduce falls under external loads (Medical Devices, Wearables)

- Tools/products/workflows: FAT2-inspired torso and hip assistance profiles; state estimation from IMUs; adaptive tilt under perturbations; clinical gait training protocols.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Patient-specific tuning; comfort, weight, and battery constraints; clinical validation and regulatory clearance.

- Cloud training pipelines for forceful WBC (Software, AI Infrastructure)

- Tools/products/workflows: Curriculum and domain-randomization “recipe” as managed service; plug-in reward modules (FAT2 variants); sim-to-real toolchain with auto-tuning of hyperparameters.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scalable GPU resources; licensing for simulators/datasets; IP and safety validation frameworks for deployed policies.

Notes on key assumptions and dependencies across applications

- Sensing: The deployed policy infers interaction forces implicitly; adding wrist force–torque sensors would likely improve reliability and safety for high-stakes tasks.

- Surfaces and traction: Many tasks depend on sufficient ground friction; hardware solutions (shoe soles, footpads) or active compliance may be necessary.

- Hardware: Torque-controlled, sufficiently powerful joints with high-frequency control loops (≥500 Hz torque) are assumed; endurance and thermal limits must be managed.

- Safety and certification: Close human interaction requires compliance with relevant standards (e.g., ISO 13482) and organizational policies; long-term uses demand formal certification.

- Environment preparation: Simple end-effector adapters and handle fixtures can dramatically expand feasible tasks; building integration (elevators, door types) unlocks autonomy at scale.

- Human-in-the-loop: Near-term deployments benefit from VR teleoperation for precision while Thor provides whole-body stabilization under load; autonomy layers can be added progressively.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.