ATLAS: Adaptive Transfer Scaling Laws for Multilingual Pretraining, Finetuning, and Decoding the Curse of Multilinguality (2510.22037v1)

Abstract: Scaling laws research has focused overwhelmingly on English -- yet the most prominent AI models explicitly serve billions of international users. In this work, we undertake the largest multilingual scaling laws study to date, totaling 774 multilingual training experiments, spanning 10M-8B model parameters, 400+ training languages and 48 evaluation languages. We introduce the Adaptive Transfer Scaling Law (ATLAS) for both monolingual and multilingual pretraining, which outperforms existing scaling laws' out-of-sample generalization often by more than 0.3 R2. Our analyses of the experiments shed light on multilingual learning dynamics, transfer properties between languages, and the curse of multilinguality. First, we derive a cross-lingual transfer matrix, empirically measuring mutual benefit scores between 38 x 38=1444 language pairs. Second, we derive a language-agnostic scaling law that reveals how to optimally scale model size and data when adding languages without sacrificing performance. Third, we identify the computational crossover points for when to pretrain from scratch versus finetune from multilingual checkpoints. We hope these findings provide the scientific foundation for democratizing scaling laws across languages, and enable practitioners to efficiently scale models -- beyond English-first AI.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

This paper studies how to train AI LLMs that work well in many languages, not just English. The authors create a new “rule of thumb” called ATLAS (Adaptive Transfer Scaling Law) that helps decide:

- how big a model should be,

- how much data to use, and

- how to mix languages during training

so that the model learns efficiently across different languages.

What questions the paper asks

The paper focuses on four simple, practical questions:

- Do different languages need different training “recipes” to get good results?

- Which languages help each other when trained together, and which ones get in each other’s way?

- What is the “curse of multilinguality”—does adding more languages make each one perform worse unless we increase model capacity?

- Is it better to train a model from scratch or start from an existing multilingual model and “finetune” it for one language?

How they studied it (in everyday terms)

Think of training a model like teaching a student:

- “Model size” is how big the student’s brain is (number of parameters).

- “Data” (tokens) are the words and pieces of words the student reads.

- “Compute” is the total effort—how long and how hard the student studies.

Here’s what they did:

- Ran a very large set of experiments: 774 model trainings with sizes between 10 million and 8 billion parameters, across more than 400 training languages, and tested on 48 languages using the MADLAD-400 dataset.

- Trained different types of models:

- Monolingual models (one language),

- Bilingual models (two languages),

- Massively multilingual models (many languages trained together).

- Measured and compared results under different conditions (bigger models, more data, different language mixes).

They also introduced a new approach—ATLAS:

- ATLAS separates the data into three parts: 1) data from the target language you care about, 2) data from a few “helper” languages that are expected to transfer well, 3) all other languages in the mix.

- It accounts for repeated reading: if the model reads the same language data many times (multiple “epochs”), it gets diminishing returns—just like reading the same book over and over.

- ATLAS learns how much each part actually helps, instead of assuming all languages help the same amount.

They built a “language help map”:

- A big 38×38 chart that shows how much one language helps another when trained together. This is called a transfer matrix.

They modeled the “curse of multilinguality”:

- When you add more languages, each language’s performance can drop unless you increase either model size or total data.

- They measured how much you need to scale model size and data to keep performance steady when adding languages.

They compared “pretrain vs finetune”:

- Pretrain from scratch: teach a “new student” starting from zero.

- Finetune from multilingual checkpoint: start with a student who already knows many languages, then focus on one language.

- They found the “crossover point” where pretraining becomes better than finetuning, depending on data and model size.

What they found and why it matters

Here are the main takeaways:

- ATLAS predicts performance better than older rules

- It beats well-known scaling laws (like Chinchilla and others), especially in multilingual settings.

- It generalizes well to larger models, more data, and unseen language mixtures.

- Why this matters: You can plan training more confidently, saving time and compute.

- Not all languages help equally—and help isn’t always mutual

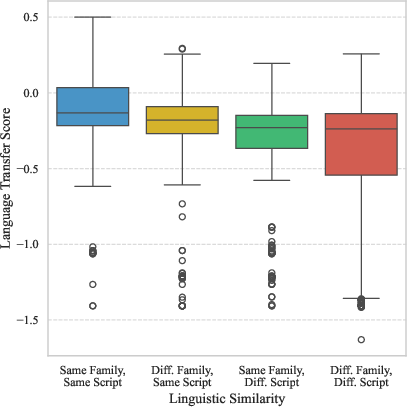

- Languages with similar scripts (like both using Latin letters) and similar families (like Spanish and Portuguese) usually help each other more.

- English is often helpful, but not always the most helpful, and the help is not guaranteed to go both ways.

- Why this matters: You can choose the smartest mix of languages to train together.

- The “curse of multilinguality” is real but manageable

- Adding more languages can hurt each one’s performance if the model is too small or the data is too limited.

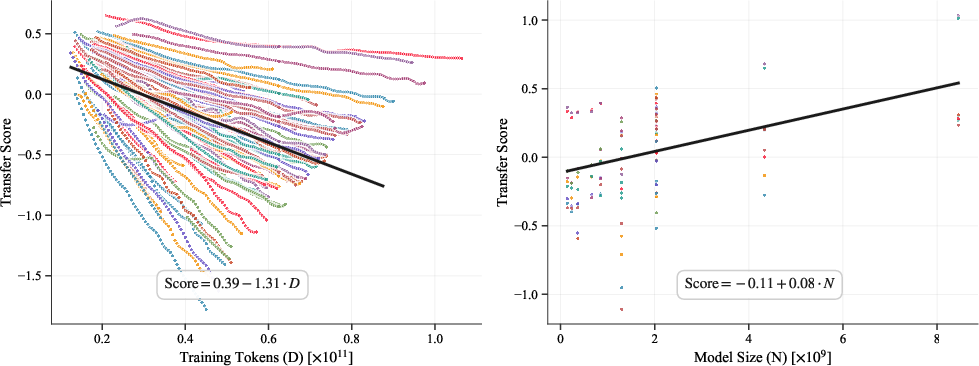

- The fix: Grow both the model size and total data. Growing model size helps more than just adding data.

- They give simple rules: if you want to serve r times more languages, you should increase total data by about r0.97 times and also increase model size. Example: going from K to 4K languages, increase total data about 2.74× and model size about 1.4×.

- Why this matters: You can expand language coverage without sacrificing quality.

- Pretrain vs finetune depends on your budget

- If you have a smaller data/compute budget, finetuning a multilingual base model is usually better.

- If you have a large budget (roughly more than 144–283 billion tokens for 2B-parameter models), pretraining from scratch eventually wins.

- They also provide a simple relation tying model size to the needed compute at the crossover point.

- Why this matters: You can choose the most cost-effective training strategy.

What this means for the future

- Better multilingual models for everyone: ATLAS helps make training fairer and more efficient across many languages, not just English.

- Smarter data and compute planning: Teams can predict how big a model should be and how much data to use when adding languages, reducing waste.

- Practical guidance: The transfer matrix and the pretrain-vs-finetune rules offer hands-on tools for building global AI systems.

- Democratization of AI: With clearer, more accurate scaling laws, smaller groups and non-English communities can train useful models without huge trial-and-error costs.

In short, this paper gives a clearer, tested roadmap for training LLMs that serve people in many languages—more efficiently, more fairly, and with better results.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper.

- Generalization beyond MADLAD-400: All results are derived on MADLAD-400 (CommonCrawl-based). It is unclear whether ATLAS, transfer matrices, and multilingual capacity findings hold across other multilingual corpora with different domain distributions, quality, and noise profiles.

- Downstream task validity: The study evaluates vocabulary-insensitive pretraining loss only. It does not test whether ATLAS’s predictions translate to downstream task performance (e.g., QA, MT, summarization) or cross-lingual benchmarks, limiting practical impact assessment.

- Tokenizer and vocabulary effects: The reported “compute-efficiency tax” for multilingual vocabularies is not mechanistically dissected. No controlled experiments vary tokenizer type (SentencePiece vs. BPE), vocabulary size, per-language vs. shared vocabularies, or transliteration to isolate how script/subword segmentation contributes to transfer and tax.

- Script vs. family causal mechanism: While script correlates more strongly than family with transfer, this remains correlational. Controlled interventions (e.g., forcing shared subword vocabularies, transliteration, synthetic token mapping) are needed to establish causal mechanisms and quantify effect sizes.

- Data repetition modeling assumptions: ATLAS uses a single repetition parameter λ shared across all data sources and requires per-language unique-token estimates U. The paper does not validate whether λ should be language-specific, nor how sensitive fits are to U estimation errors (especially for low-resource languages).

- Estimation of unique tokens U: The method for estimating per-language U (unique tokens) is unspecified. Robustness to deduplication strategies, language identification errors, and crawl noise is untested—potentially undermining the accuracy of repetition-aware modeling.

- “Other languages” lumping: The τ_other term aggregates all non-target, non-selected transfer languages into a single coefficient, potentially blending helpful and harmful sources. A more granular approach (e.g., learned clustering or sparse per-language weights) could improve predictive fidelity for unseen mixtures.

- Choice and size of transfer set K_t: ATLAS selects the top-3 co-sampled languages as transfer sources. There is no sensitivity analysis on the number of transfer languages, selection criteria (e.g., by measured BTS vs. sampling rate vs. typological similarity), or whether dynamic/adaptive selection during training improves fit and generalization.

- Transfer matrix scope and ratios: The bilingual transfer matrix is measured primarily at a 50/50 sampling ratio on 2B-parameter models. It does not characterize how transfer varies with:

- Model size N (e.g., 10M–8B or larger),

- Training tokens D (including repetition),

- Asymmetric sampling ratios,

- Many-to-many mixtures (tri-lingual or >2 language blends).

- Asymmetry of transfer: The paper’s analysis reports near-diagonal clusters suggesting symmetry but also cites an overall Pearson r ≈ −0.11. The causes of asymmetry (e.g., resource imbalance, script incompatibility, vocabulary overlap, morphology) remain unexplained and unmodeled.

- Low-resource language behavior: Negative transfer reported for some low-resource languages (e.g., Urdu, Pashto) lacks actionable prescriptions. How to identify and mitigate harmful sources (e.g., reweighting, temperature sampling, filtering) is not addressed.

- Model-size coverage and consistency: The paper cites ranges of 10M–2B and 10M–8B inconsistently. It does not assess whether ATLAS parameters/exponents are stable across substantially larger models (e.g., 13B–70B), or whether the laws extrapolate to modern frontier-scale regimes.

- Capacity law variability across languages: The global exponents (φ ≈ 0.11, ψ ≈ −0.04) for the curse of multilinguality are reported across 8 languages and the combined set. Per-language variability, confidence intervals, and conditions under which ψ flips sign (from positive to negative transfer) are not analyzed.

- Uniform sampling assumption in capacity analysis: Iso-loss and capacity results assume uniform sampling across languages. Real mixtures are heavily skewed. A generalized law that incorporates uneven sampling ratios and their interaction with φ, ψ, α, β is missing.

- Compute model simplifications: Compute is approximated as C = 6ND. The study does not account for sequence length, optimizer, parallelism efficiency, hardware differences, or activation checkpointing—limiting applicability to real-world budget planning.

- Pretrain vs. finetune mechanism: The finding that finetuned multilingual checkpoints are initially superior but get surpassed by scratch pretraining is left unexplained. Potential mechanisms (initial alignment, catastrophic forgetting, distribution mismatch, saturation effects) merit investigation.

- Generality of the pretrain–finetune crossover: The crossover formula log(C) = a·N1.65 is derived using a single Unimax checkpoint trained for ~1B tokens and a specific mixture. Sensitivity to checkpoint training length, mixture composition, sampling policies, and pretraining quality is not studied.

- Data quality and filtering: The impact of data quality, filtering rigor, and domain composition on scaling-law parameters and transfer scores is not quantified, despite known sensitivity of scaling to noise and curation.

- Code-switching and mixed-script scenarios: The study does not evaluate code-switching, intra-document multilinguality, or mixed-script text—common in real-world multilingual corpora—and how these affect transfer and capacity constraints.

- Instruction tuning and adaptation: The laws are fit to pretraining. It remains unknown whether similar transfer/capacity dynamics hold during instruction tuning, RLHF, or domain-specific continued pretraining, and how multilinguality interacts in those regimes.

- Downstream fairness and parity: The paper does not evaluate whether ATLAS-guided scaling preserves parity across languages (especially low-resource ones) on real tasks, nor whether capacity penalties translate into inequitable performance gaps.

- Release and reproducibility: The availability of code, fitted parameters (E, A, B, α, β, λ, τ_i, τ_other), per-language U estimates, and the full 38×38 transfer matrix is not specified, limiting independent validation and broader use.

- Interaction effects in larger mixtures: The bilingual transfer matrix cannot capture higher-order interaction effects (e.g., triads where A helps B, B helps C, but A harms C). A framework to model non-additive interactions in multilingual mixtures is lacking.

- Impact of context length: The paper does not examine whether longer context windows alter scaling exponents, transfer properties, or multilingual capacity penalties.

- Robustness to language identification errors: MADLAD-400’s language detection is assumed accurate; the sensitivity of transfer and capacity conclusions to misclassification or script noise is not explored.

- Practical guidance for mixture optimization: Although ATLAS improves prediction, actionable algorithms to construct multilingual mixtures (e.g., reweighting by predicted τ_i, dynamic curricula, temperature schedules) are not provided or validated.

- Confidence intervals and uncertainty quantification: Reported R2 improvements lack uncertainty estimates on fitted parameters, making it difficult to assess stability under resampling or different train–test splits.

- Extending ATLAS beyond loss: The paper does not probe whether ATLAS can predict cross-lingual generalization metrics (e.g., zero-shot transfer, bilingual lexical overlap), or guide tokenizer design choices, leaving broader applicability open.

Glossary

- Adaptive Transfer Scaling Law (ATLAS): A repetition-aware scaling law that separates target, transfer, and other language data contributions for mono/multilingual pretraining. "We introduce the Adaptive Transfer Scaling Law (ATLAS) for both monolingual and multilingual pretraining, which outperforms existing scaling laws' out-of-sample generalization often by more than $0.3$ ."

- Bilingual Transfer Score (BTS): A metric quantifying how much training in a source language accelerates or hinders reaching a target language’s loss compared to monolingual training. "We define a Bilingual Transfer Score (BTS) as the relative training efficiency of a bilingual model compared to the monolingual model at reaching the same loss level."

- Chinchilla Scaling Law (CSL): A widely used scaling law formulation from Chinchilla that models loss as a function of parameters and data. "Scaling laws for English are typically based on Chinchilla \citep{hoffmann2022training}---which we refer to as the Chinchilla Scaling Law (CSL)."

- Compute-efficiency tax: An observed penalty where training with multilingual vocabularies or datasets requires more compute to reach the same performance. "We find (1) per-language optimal scaling trajectories are similar, (2) there is a compute efficiency tax for training with multilingual vocabularies or training sets (especially for English), and (3) as Hindi and Swahili observe data repetition their curves slope upward from diminishing returns."

- Cross-Lingual Transfer Matrix: A matrix of empirically measured transfer scores capturing how co-training in one language affects another. "First, we derive a cross-lingual transfer matrix, empirically measuring mutual benefit scores between language pairs."

- Curse of Multilinguality: The phenomenon where adding languages to the training mixture degrades per-language performance due to limited model capacity. "A model's capacity can hinder its ability to learn multiple languages at once---known as the curse of multilinguality \citep{conneau2019unsupervised, chang2024multilinguality}."

- Data-Constrained Scaling Law (DCSL): A scaling law that accounts for diminishing returns when data is repeated across multiple epochs. "requiring a Data-Constrained Scaling Law (DCSL) \citep{muennighoff2024scaling} to account for diminishing returns after multiple epochs."

- Effective data exposure (D_eff): A composite term representing the net useful data seen by the model, combining target, transfer, and other-language tokens with repetition saturation. "Its effective data exposure term $D_{\mathrm{eff}$ (\Cref{eq:scl-deff}) unpacks data sources into three terms: a $\textcolor{d_target}{\text{Monolingual}$ term for the target language data , an optional $\textcolor{d_transfer}{\text{Transfer Language}$ term ... and an $\textcolor{d_other}{\text{Other Languages}$ remainder term..."

- Finetune: Continue training a pretrained base model (e.g., multilingual checkpoint) on a target language/task. "Depending on the token (or compute) budget, it is usually more effective to finetune a multilingual checkpoint if there are tokens, and pretrain from scratch if the budget accommodates tokens."

- Irreducible loss: The asymptotic loss floor the model cannot improve beyond, even with unlimited data or parameters. "includes the standard parameters governing the irreducible loss and scaling: ."

- Iso-loss frontier: The set of combinations of model size and data that keep loss constant when scaling the number of training languages. "In \Cref{fig:capacity_add_lang_isoloss_curve} we plot the iso-loss frontiers, and compute-optimal allocations, when scaling a model from to languages."

- Language-agnostic scaling law: A scaling-law formulation that applies uniformly across languages, independent of language identity. "Second, we derive a language-agnostic scaling law that reveals how to optimally scale model size and data when adding languages without sacrificing performance."

- Language Transfer Score: A normalized measure of cross-lingual transfer/interference used to populate the transfer matrix. "The Cross-Lingual Transfer Matrix, depicting the measured Language Transfer Score across language pairs."

- MADLAD-400: A CommonCrawl-derived multilingual pretraining dataset with coverage of 400+ languages. "We use the MADLAD-400 dataset \citep{kudugunta2024madlad}, a popular CommonCrawl-based dataset with the most expansive coverage of languages, totaling over 400."

- Multilingual Scaling Law (MSL): A scaling law that models target-language loss using parameters, data, and the sampling ratio of its language family in the mixture. "or \citet{he2024scaling} introduce Multilingual Scaling Law (MSL), which expresses the loss for target language using and the sampling ratio for the target languages' language family in the training mixture."

- Positive transfer: Beneficial cross-lingual transfer where co-training improves learning efficiency for a target language. "Positive scores indicate more positive transfer, negative scores more interference, during bilingual co-training."

- Power law: A functional relationship where performance or loss scales as a power of model size or data. "we can estimate a best fit power law in \Cref{fig:modelsize_vs_finetune_intersection}, relating to ."

- Saturation function: A function that reduces the effective contribution of additional tokens after exceeding a language’s unique-token budget (multi-epoch repetition). "For each term, we apply a saturation function (\Cref{eq:scl-sat-piecewise}), ensuring a smooth decay on the effective data for each subsequent epoch..."

- Sentence Piece Model: A subword tokenization method used to build fixed-size vocabularies for multilingual training. "We use a 64k Sentence Piece Model vocabulary \citep{kudo2018sentencepiece}."

- Unimax checkpoint: A massively multilingual base model checkpoint used for warm-starting finetuning. "whether it is more efficient to pretrain from scratch or begin from a multilingual Unimax checkpoint"

- Vocabulary-insensitive loss: An evaluation metric designed to compare losses fairly across languages and vocabularies. "to evaluate vocabulary-insensitive loss \citep{tao2024scaling} for fairer cross-lingual comparisons."

Practical Applications

Overview

This paper introduces ATLAS (Adaptive Transfer Scaling Law) and complementary empirical resources to plan, predict, and optimize multilingual LLM training. Key deliverables include:

- A repetition-aware scaling law that separates target, transfer, and “other” language contributions, improving out-of-sample generalization in both monolingual and multilingual settings.

- A 38×38 cross‑lingual transfer matrix quantifying language–language synergy and interference.

- A capacity/curse‑of‑multilinguality scaling model with iso‑loss formulas to scale compute, model size, and data when adding languages.

- Practical crossover guidance on when to pretrain from scratch vs. finetune from a multilingual checkpoint.

Below are concrete applications, grouped by deployment horizon. Each item notes typical sectors, candidate tools/products/workflows, and key assumptions/dependencies.

Immediate Applications

Industry

- Multilingual training budgeter and planner

- What: Forecast per‑language loss vs. model size N, tokens D, and number of languages K using ATLAS (with data repetition saturation) to choose compute‑optimal trajectories.

- Tools/Workflows: “ATLAS Planner” notebook/dashboard; inputs: language list, token targets, estimated unique tokens U per language; outputs: predicted loss, N–D trade‑offs, and compute C≈6ND.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Architecture and tokenization similar to the study (decoder LMs, 64k SPM); domain close to MADLAD‑400; reasonable estimates of U and repetition.

- Language expansion roadmap (iso‑loss scaling)

- What: Use the iso‑loss formulas to expand language coverage from K→rK without degrading existing languages. Paper estimates compute should scale ≈C·r0.97; example: 4× more languages requires ~2.74× total tokens and ~1.4× model size in their setting.

- Tools/Workflows: “LangExp Planner” that returns N′/N=r{φ/α}, D′/D=r{1+ψ/β}; budget proposals and capacity requests tied to r.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Coefficients (φ≈0.11, ψ≈−0.04) are estimated on 10M–8B models and MADLAD‑400; α,β depend on your model family; even language sampling.

- Pretrain vs. finetune decisioning

- What: For a target language, determine when warm‑starting from a multilingual checkpoint is better than pretraining from scratch. Empirically, for 2B models, finetuning wins if you have <~144B target tokens; pretraining can surpass after ~144–283B tokens (language‑dependent). Crossover compute grows superlinearly with model size (~N1.65 trend).

- Tools/Workflows: “Crossover Calculator” that compares projected learning curves; procurement/planning gates for data and compute readiness.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Base checkpoint comparable to the Unimax setup in the paper (mixture/steps matter); crossovers shift with mixture quality, domain match, and tokenizer.

- Data mixture design via the cross‑lingual transfer matrix

- What: Choose co‑training languages that maximize positive transfer and avoid interference; prioritize same‑script and related‑family pairs; use top‑k transfer partners when target data is scarce.

- Tools/Workflows: “MixOpt” recommender that proposes sampling ratios and co‑training bundles; A/B mixtures validated with held‑out R2(M).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reported transfer scores are from 2B models; transfer may shift with model size, tokenizer, and domain; ensure your target/source languages are covered or re‑estimate.

- Tokenization and vocabulary strategy to avoid compute tax

- What: For English‑only systems, prefer monolingual vocabularies and monolingual training to avoid the observed compute‑efficiency tax of multilingual vocab/training; for multilingual products, quantify the trade‑off explicitly with ATLAS.

- Tools/Workflows: “Vocab Impact Estimator” comparing mono vs. multi SPM; tokenizer ablations in training plans.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: The observed tax is setup‑dependent; script overlap interacts strongly with subword sharing.

- Repetition-aware scheduling and deduplication

- What: Use the saturation function Sλ(D;U) to down‑weight repeated epochs; allocate budget to scale N over continuing to cycle repeated data; set stop‑criteria per language.

- Tools/Workflows: “Effective Data Exposure” metrics in MLOps; per‑language dedup and unique‑token estimation; training dashboards flagging diminishing returns.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Requires robust language identification, deduplication, and U estimation; λ tuned on your corpus.

- Sector‑specific deployments

- Healthcare: Build multilingual clinical assistants by pairing targets with high‑transfer sources (same script/family); finetune checkpoint if limited target tokens.

- Finance/Legal: Document processing across languages; stage rollouts using iso‑loss budgeting; select co‑training languages to stabilize low‑resource compliance locales.

- Software/Consumer: Multilingual chat/agent features; plan feature‑by‑feature language additions with r‑scaling; minimize latency/cost via compute‑optimal mixtures.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Domain shift vs. web pretraining; need in‑domain data for safety/accuracy.

Academia

- Rigorous scaling‑law evaluation protocols

- What: Adopt held‑out axes R2(N), R2(D), R2(C), R2(M) to avoid overfitting scaling laws and to test mixture generalization.

- Tools/Workflows: Open benchmarks/splits; replication checklists for multilingual scaling work.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Consistent preprocessing, vocabulary, and evaluation losses across languages.

- Experimental design using transfer scores

- What: Choose language pairs and scripts to test symmetry/asymmetry; focus on families/scripts where effects are strongest; plan sample‑efficient studies with bilingual co‑training.

- Tools/Workflows: “Transfer Explorer” to interrogate score symmetry and cluster structures.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Transfer can be size‑ and domain‑dependent.

Policy and Public Sector

- Language equity budgeting and roll‑out plans

- What: Use iso‑loss scaling to justify compute grants and staged deployments for underserved languages; quantify cost to add r new languages without degrading existing ones.

- Tools/Workflows: Budget models tied to r0.97 compute scaling; per‑language performance targets in RFPs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Coefficients calibrated to government‑domain data; environmental cost assessments.

- Procurement and transparency requirements

- What: Require per‑language mixture disclosure, scaling‑law forecasts, and measured cross‑lingual effects before procurement/deployment.

- Tools/Workflows: Standardized “Language Coverage Plan” sections in tenders and model cards.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Vendors able to expose mixtures and evaluation details.

Daily Life and Startups

- Practical build–vs–adapt guidance

- What: Small teams launching multilingual chatbots or support tools should finetune strong multilingual checkpoints unless they have ≥O(1011) tokens in the target language; pick co‑training languages with same script/family for better outcomes.

- Tools/Workflows: Lightweight calculators/spreadsheets; curated language bundles per market.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of high‑quality checkpoints and license compatibility; careful evaluation for safety.

Long‑Term Applications

Industry

- AutoML for multilingual mixture optimization

- What: ATLAS‑driven controllers that adapt sampling ratios online to maximize per‑language progress under compute caps; couple with data‑quality filters.

- Tools/Workflows: “AutoMix” service integrating ATLAS loss predictions in the training loop; reinforcement or bandit controllers.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable online evaluation; stable ATLAS fit during curriculum changes.

- Curriculum schedulers and dynamic language onboarding

- What: Start with high‑transfer languages, then progressively add harder/low‑resource languages along iso‑loss frontiers; re‑budget N and D per milestone.

- Tools/Workflows: “Curriculum Orchestrator” coordinating model re‑sizing and mixture updates.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Smooth transferability across curricula; checkpoint compatibility.

- Architecture choices guided by transfer (e.g., MoE, script‑aware tokenization)

- What: Design experts/routers by script or family; tokenize by script groups to maximize subword sharing where beneficial, isolate where interference is high.

- Tools/Workflows: “Transfer‑Informed Router” design kits; tokenizer co‑design with mixture optimization.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Transfer patterns persist at larger scales; engineering complexity vs. gains.

- Cloud offerings and SLAs for language expansion

- What: Standardize “cost to add a language” estimates and SLAs based on r‑scaling; offer expansion quotes with compute/latency forecasts.

- Tools/Workflows: Provider calculators; language expansion contracts.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Provider‑specific hardware/efficiency; customer domain alignment.

- Sustainability and cost governance

- What: Use compute‑optimal scaling to reduce over‑training in repeated‑epoch regimes; keep energy/water budgets aligned with iso‑loss targets.

- Tools/Workflows: “Green Scaling” dashboards linking ATLAS to carbon/water estimators.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate metering; organizational incentives.

Academia

- Extending scaling laws to other modalities and stages

- What: Apply ATLAS‑style separation (target/transfer/other) to instruction‑tuning, retrieval‑augmented pretraining, speech, OCR, and code; study phase transitions with size.

- Tools/Workflows: Shared multilingual corpora with curated U estimates; cross‑modality transfer matrices.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Comparable loss measures and tokenization notions across modalities.

- Theoretical understanding of asymmetric transfer

- What: Formal models predicting when A→B transfer differs from B→A; connect to typology, morphology, and subword overlap.

- Tools/Workflows: Joint linguistic–ML studies; controlled synthetic languages.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Cleanly isolating script and family effects from data quality.

Policy and Public Sector

- National language coverage programs

- What: Plan multi‑year, compute‑bounded roadmaps to cover all official/minority languages without performance regression; fund open transfer matrices as public goods.

- Tools/Workflows: National “Language Expansion Plans” with r‑scaling and target parity metrics.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Public–private data sharing; approvals for open publication.

- Standards for cross‑lingual transparency and parity

- What: Require per‑language reporting, mixture disclosure, and iso‑loss planning in audits; tie subsidies to demonstrated parity improvements for low‑resource languages.

- Tools/Workflows: Certification checklists; third‑party evaluation bodies.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Agreement on parity metrics; legal frameworks for disclosure.

Daily Life and Startups

- On‑device bilingual/multilingual assistants with language packs

- What: Predict which language pairs can share a compact model effectively (same script/family), and which require separate packs; deliver dynamic downloads.

- Tools/Workflows: “Language Pack Manager” using ATLAS forecasts to size packs and switch routing.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Efficient distillation/quantization; privacy constraints.

- EdTech and community translation tools

- What: Leverage high‑transfer source languages to bootstrap learning resources and translation for closely related, low‑resource languages; expand coverage stepwise using iso‑loss plans.

- Tools/Workflows: Community platforms prioritizing high‑transfer pairs first; staged corpus building.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Volunteer/community engagement; guardrails for quality and bias.

Cross‑Cutting Assumptions and Dependencies

- Scale and domain: Findings are calibrated on 10M–8B models and web‑like corpora (MADLAD‑400); coefficients may shift at tens of billions of parameters, other architectures, or domains (clinical, legal, code).

- Tokenization and scripts: Strong script effects reflect subword sharing; changing vocabulary size or tokenizer can alter transfer/interference.

- Checkpoints and mixtures: Pretrain‑vs‑finetune crossovers depend on the base checkpoint mixture, training length, and domain match; Unimax assumptions may not hold universally.

- Data repetition and U: Accurate unique‑token U estimates and deduplication are required to use Sλ(D;U) effectively.

- Evaluation rigor: Adopt held‑out axes R2(N/D/C/M) to avoid misleading fits; monitor per‑language metrics post‑deployment.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.