SoftMimic: Learning Compliant Whole-body Control from Examples (2510.17792v1)

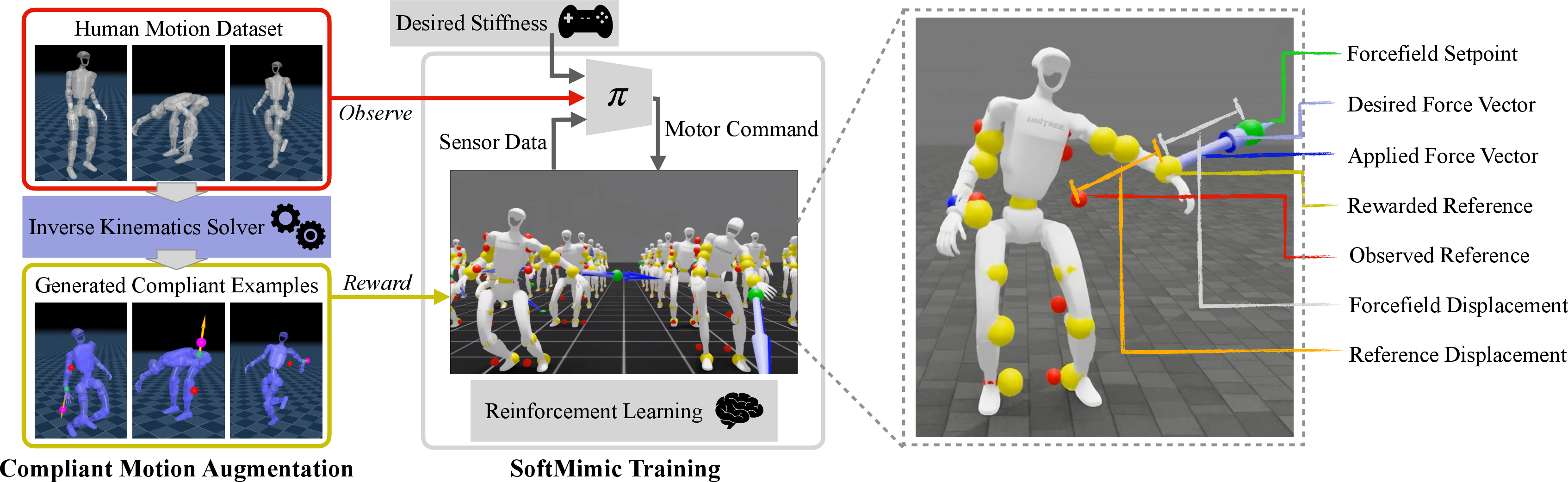

Abstract: We introduce SoftMimic, a framework for learning compliant whole-body control policies for humanoid robots from example motions. Imitating human motions with reinforcement learning allows humanoids to quickly learn new skills, but existing methods incentivize stiff control that aggressively corrects deviations from a reference motion, leading to brittle and unsafe behavior when the robot encounters unexpected contacts. In contrast, SoftMimic enables robots to respond compliantly to external forces while maintaining balance and posture. Our approach leverages an inverse kinematics solver to generate an augmented dataset of feasible compliant motions, which we use to train a reinforcement learning policy. By rewarding the policy for matching compliant responses rather than rigidly tracking the reference motion, SoftMimic learns to absorb disturbances and generalize to varied tasks from a single motion clip. We validate our method through simulations and real-world experiments, demonstrating safe and effective interaction with the environment.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces SoftMimic, a new way to control humanoid robots so they can move like people but still stay safe and “soft” when they bump into things. Instead of acting like a rigid machine that fights any push, SoftMimic teaches robots to yield like a spring when touched, while keeping their balance and overall pose. The key idea is a “stiffness” knob you can set: low stiffness makes the robot softer and more gentle; high stiffness makes it resist more strongly.

What questions are the researchers asking?

- How can a robot copy a human motion (like walking, reaching, or picking up a box) but still react safely to unexpected bumps or contact?

- Can we give the robot a simple control dial (stiffness) so it knows how much to yield—like choosing how squishy a spring should be?

- Can one learned controller handle many different pushes, objects, and surprises without breaking or acting dangerously?

- Can the robot stay gentle when it should (for safety) but still track the motion well when nothing is touching it?

How did they do it?

The authors combine two main tools—“make soft examples first” and “learn to follow them”—so the robot can copy both the style of the motion and the safe, compliant reactions to contact.

Key idea 1: A “softness” dial (stiffness)

- Think of the robot’s hand like it’s attached to the body with a spring.

- If you push the hand, a soft spring gives easily (low stiffness); a stiff spring resists (high stiffness).

- The robot gets a stiffness command at run-time, so you can make it gentle or firm as needed.

Key idea 2: Make examples of soft reactions (offline “inverse kinematics”)

- Inverse kinematics (IK) is like solving a puzzle: “What joint angles put the hand here while keeping the rest of the body balanced and in a natural pose?”

- The team takes a normal human-like motion (the “reference”), imagines different pushes on the robot (forces), and uses IK to create “what a good, safe, soft reaction should look like” for the whole body.

- This produces many example motions showing how to yield safely without losing style or falling over. They also filter out impossible cases (so the robot isn’t asked to do what it can’t).

Key idea 3: Teach a policy to copy those examples (reinforcement learning)

- A policy is a brain that maps what the robot feels to what it should do next.

- The robot “feels” its own body sensors (proprioception), like joint angles and speeds, but not the external force directly. It learns to infer the pushes from how its body responds.

- During training, the robot sees the original motion but is rewarded for matching the “soft reaction” version created by IK. This nudges it to learn compliant responses instead of rigidly forcing the original pose.

Training touches that make it work in the real world

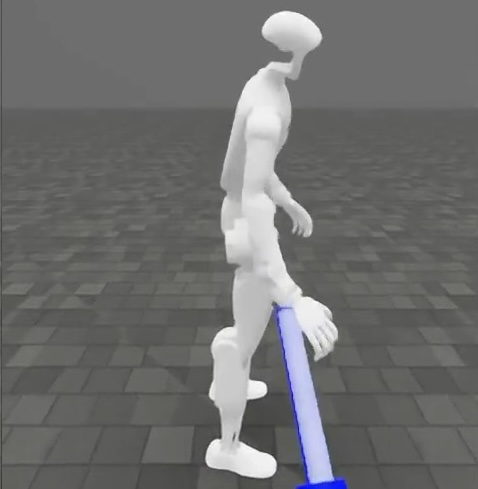

- Force fields: During training, the robot is “pulled” or “pushed” in different ways to simulate all kinds of contacts—from soft environments (like a cushion) to hard ones (like a wall).

- Reasonable stiffness range: They choose a practical range of stiffness values that the robot can actually achieve given noisy sensors.

- Simple, reliable control signals: The policy sends joint position targets to the motors (like aiming each joint at a point with a spring-damper), which is a common, robust way to control real robots.

What did they find, and why is it important?

Here are the main takeaways from tests in simulation and on a real Unitree G1 humanoid:

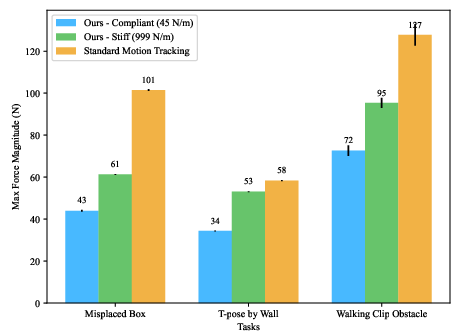

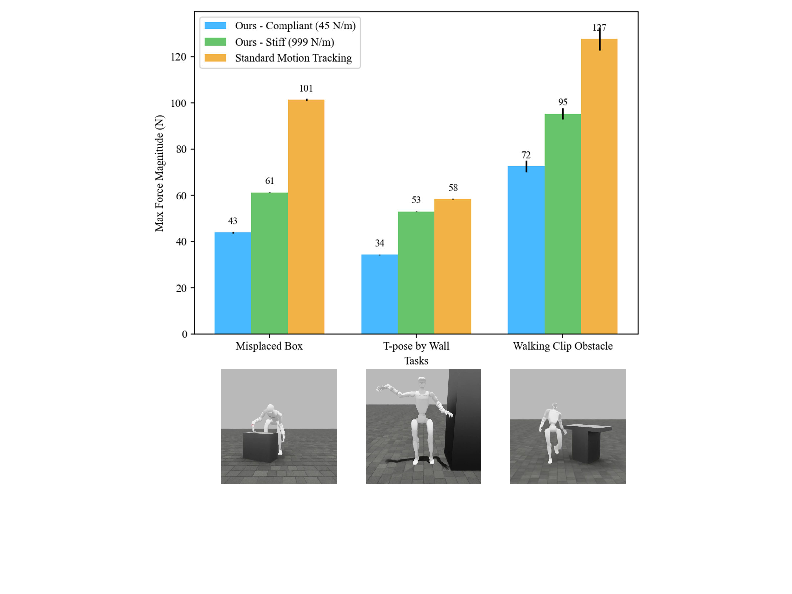

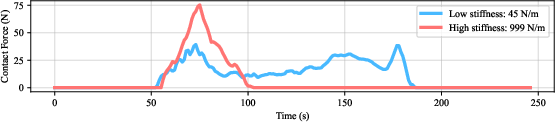

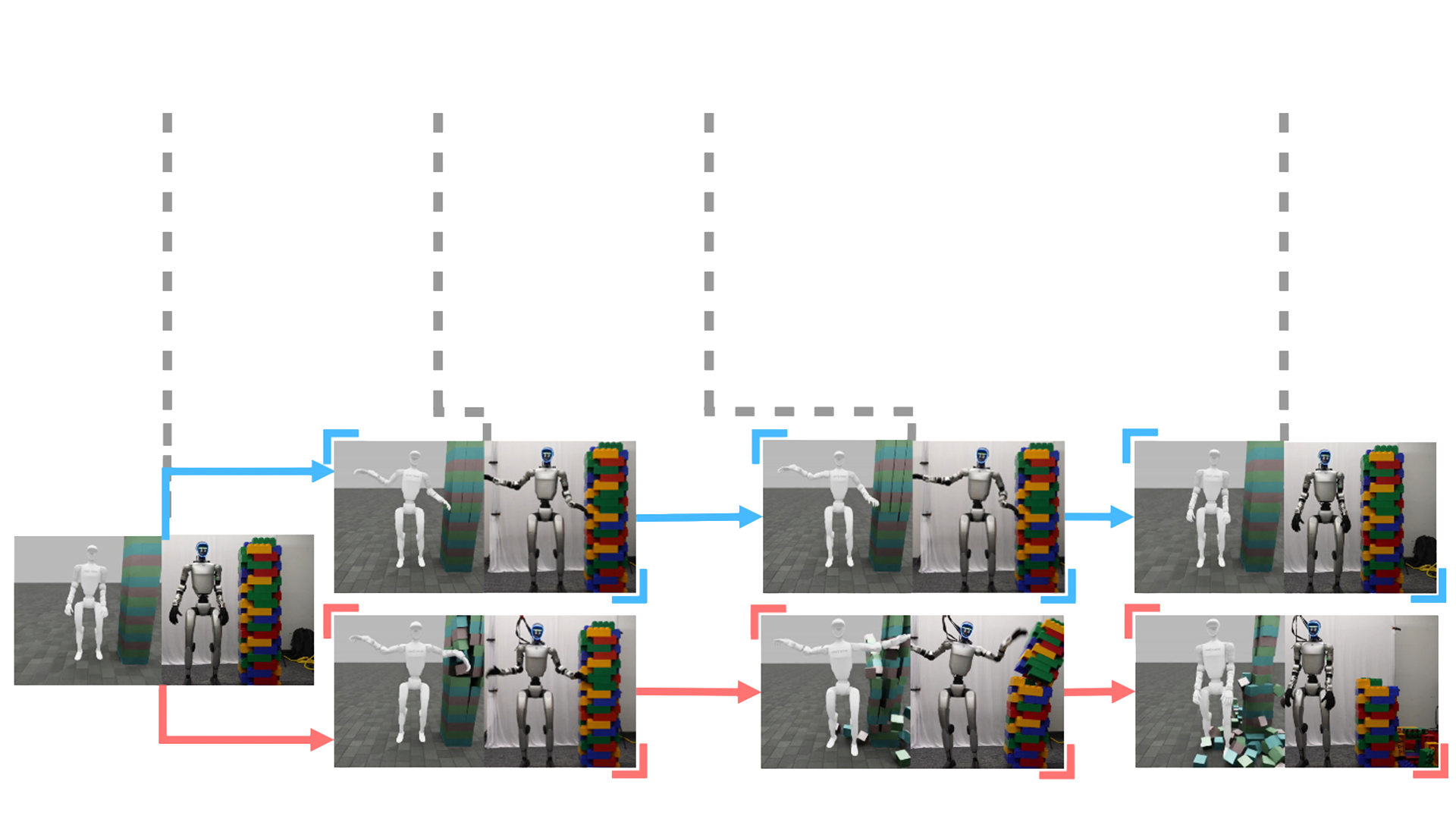

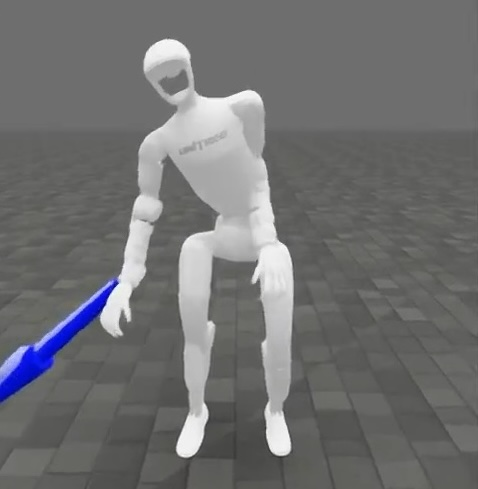

- Safer interactions: With low stiffness, the robot produces much smaller contact forces when it bumps into things (like a wall or a table corner). This reduces the chance of damage and makes it safer around people.

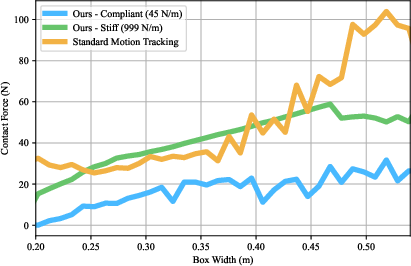

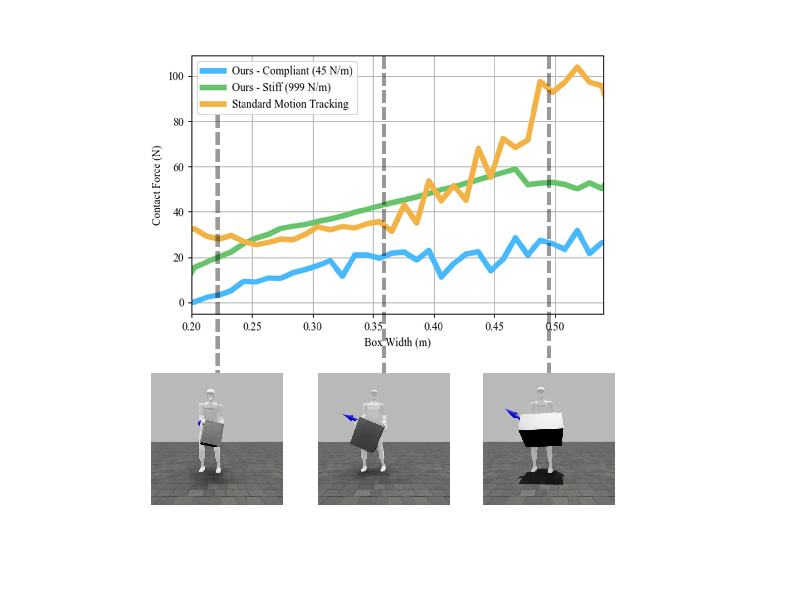

- Better generalization from one demo: Using just one motion clip (e.g., picking up a 20 cm box), the robot can gently pick up boxes of different sizes without retuning. It “squeezes” only as much as needed instead of crushing or failing.

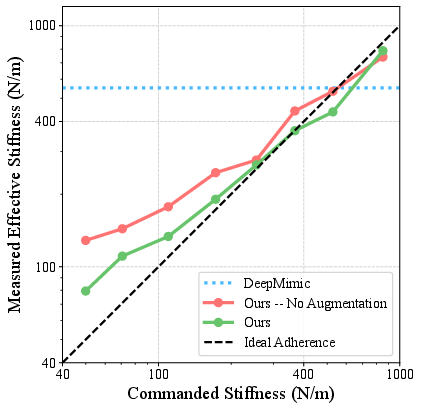

- Obeys the stiffness command: The robot’s effective “springiness” closely matches the stiffness number you set. Turn the dial down, it yields more; turn it up, it resists.

- Keeps motion quality: When nothing is pushing on it, the robot still tracks the original motion well. You don’t have to trade away natural-looking movement to get safety.

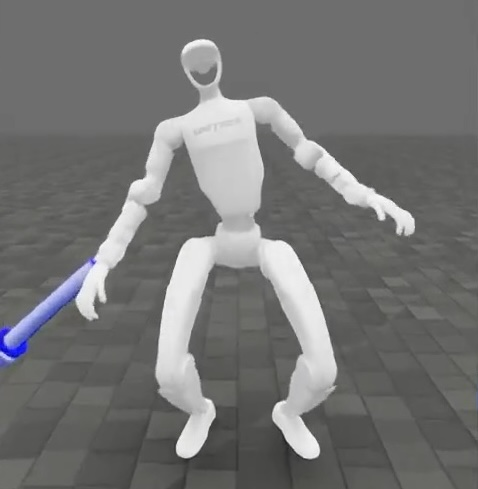

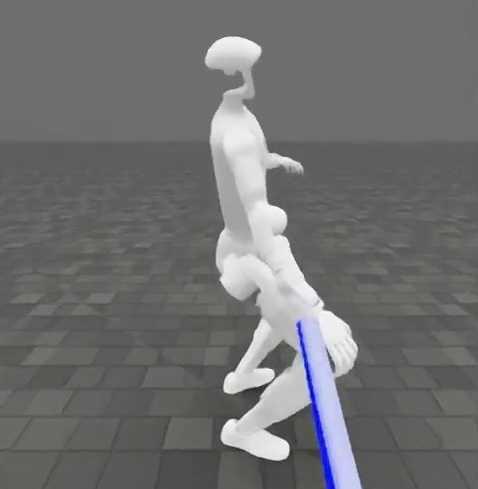

- Style control via data: By changing how the offline IK examples are made (e.g., favoring a squat vs. a bend), the learned policy adopts that whole-body “style” when it yields. This gives designers control over the look and feel of compliance.

- Works on hardware: The benefits seen in simulation also show up on the real robot, a strong sign the method is practical.

Why it matters: Robots that can be soft or firm on demand are much safer and more useful in everyday spaces. They can work around people and clutter, handle uncertainty, and still keep their balance and posture.

What’s the bigger impact?

SoftMimic points toward humanoids that:

- Interact safely with people and messy environments.

- Reuse a single motion to handle many real-world variations (object sizes, slight misplacements, unexpected bumps).

- Offer a simple safety/performance knob (stiffness) that can be tuned on the fly—for example, gentle for handing an object to a person, stiff for lifting something heavy.

In the future, this approach could:

- Learn from larger libraries of motions or live teleoperation.

- Adjust stiffness automatically based on the task and situation.

- Extend compliance across more body parts and multi-contact cases.

- Use even better example generation that includes physics, to improve realism.

Bottom line: SoftMimic shows how to teach robots not just to move like us, but to react like us—carefully and safely—when the world pushes back.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of concrete gaps, limitations, and open questions that remain unresolved and can guide future research:

- Stiffness selection and scheduling: No method is provided for automatically selecting or adapting stiffness online based on task goals, context, or risk; criteria, policies, and guarantees for dynamic stiffness scheduling are open.

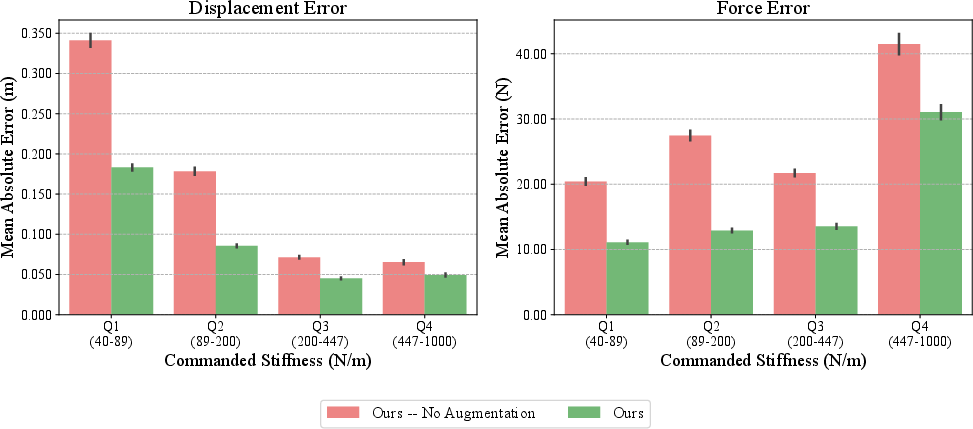

- Range limits: The approach is trained and validated over a limited stiffness range (≈40–1000 N/m linear; 0.1–10 Nm/rad angular); behavior, accuracy, and stability outside these bounds (very low/high stiffness) are not characterized.

- Mapping from commanded to effective stiffness: The relationship is not calibrated or guaranteed; nonlinearity and configuration dependence suggest the need for online calibration and adaptive mapping.

- Damping and inertia shaping: Only stiffness is explicitly commanded; full impedance (mass–spring–damper) shaping and frequency-dependent behavior are not addressed.

- Anisotropic and coupled stiffness: The method assumes isotropic diagonal stiffness; direction-dependent stiffness and non-diagonal coupling in task space remain unexplored.

- External wrench inference: The policy infers wrenches solely from proprioception and short histories; robustness to noise, latency, biases, and unmodeled dynamics on hardware is not systematically evaluated.

- Force/pose estimator details: The force estimator (≈4 N noise) is referenced but not described (architecture, training data, real-world calibration), limiting reproducibility and assessment of estimator-induced limits.

- Observation design: Root and contact states are not observed; ablations quantifying the benefits/risks of including these signals (or tactile/FT sensing) are missing.

- Baselines: Comparisons against analytical whole-body impedance/operational-space controllers and recent learning-based compliant controllers are absent, leaving relative performance and trade-offs unclear.

- Safety guarantees: There are no formal passivity, stability, or contact safety guarantees; methods to certify or enforce passivity/energy bounds in the learned controller are open.

- Multi-contact compliance: Augmentation considers single-link (hands) interactions; explicit training and evaluation for simultaneous multi-link contacts are missing.

- Whole-body coverage: Compliance is only defined for the wrists; extending to any link or distributed body regions (with differing local stiffness) is an open direction.

- Contact switching and stepping: Augmentation constrains stance feet; scenarios requiring foot re-placement, stepping, or contact switching to realize safe compliance are unsupported.

- Dynamics-aware augmentation: Augmented trajectories are kinematically feasible but may be dynamically challenging; incorporating dynamics (e.g., torque limits, momentum, friction) into augmentation is a key gap.

- Rejection sampling coverage: Feasible workspace is shaped by IK failure and rejection; quantifying coverage gaps and developing active or curriculum strategies to fill them is open.

- Metric learning: The fixed distance metric d (mix of keypoints/joints/CoP/feet) shapes style; learning this metric from data or preferences (e.g., inverse RL) could yield better null-space behavior.

- Task–stiffness trade-offs: Systematic analysis of task success vs. stiffness (e.g., for heavy lifting vs. gentle handover) and methods for context-aware switching are not provided.

- Sequential and persistent interactions: Robustness to long-duration forces, repeated impacts, and sequences of contact events is not characterized.

- Frequency response and identification: Stiffness adherence is measured via quasi-static force–displacement; operational-space impedance identification across frequencies is absent.

- Sim-to-real robustness breadth: Quantitative sim-to-real studies over diverse surfaces, friction, contact compliance, payloads, and delays are limited; domain randomization details and coverage are not reported.

- Torque and thermal limits: The method’s behavior under actuator saturation, torque/velocity limits, and thermal constraints is not analyzed; safety under saturation remains open.

- Energy and efficiency: The impact of compliant behavior on energy consumption and actuator heating is not evaluated.

- Large-scale generality: Policies are trained per-clip; scaling to large motion corpora, multi-skill policies, and live teleoperation with compliance (without catastrophic forgetting) is unaddressed.

- Morphological generalization: Transfer across different humanoid embodiments (masses, link lengths, actuators) and morphology-conditioned policies remains unexplored.

- Perception integration: The system relies on reactive compliance and proprioception; incorporating vision/tactile to anticipate contacts and select stiffness or targets remains open.

- Real-world HRI: Human–robot interaction studies (comfort, trust, safety metrics, standards compliance) and stiffness policies tuned for HRI are not presented.

- Failure handling: Strategies for when compliance conflicts with balance or task completion (e.g., when to step, abort, or increase stiffness) are not formalized.

- Reward sensitivity: Sensitivity of results to reward scales and weights, and automated methods (e.g., population-based tuning) to set them, are not investigated.

- Architecture and memory: Only short history windows are used; whether recurrent architectures or longer horizons improve wrench inference and stability is an open question.

- Low-level control interface: The policy outputs PD position targets with fixed “moderate” gains; benefits of variable-gain actions or mixed torque/position actions for passivity and fidelity remain to be tested.

- Contact modeling realism: Training uses force fields to emulate environments; alignment with real contact geometry, frictional stick–slip, and material compliance is not validated across diverse cases.

- Benchmarking and reproducibility: Standardized benchmarks for compliant humanoid whole-body control, open datasets of augmented trajectories, and full release of IK costs/weights and estimator code are needed.

Glossary

- Admittance-like environment: An environment that behaves like an admittance system, where applied forces determine motion; used to model compliant surroundings. "an admittance-like environment"

- Admittance strategy: A control approach that estimates external forces and commands motions accordingly. "For an admittance strategy"

- AMASS: A large human motion capture dataset used for training and evaluation. "AMASS"

- Apparent stiffness: The perceived spring-like resistance of the system in task space, arising from control and dynamics. "apparent stiffness"

- Back-drivability: The ease with which external forces can move an actuator or robot joint backward, indicative of safe, compliant interaction. "back-drivability"

- Center of Mass (CoM): The weighted average position of all mass in the robot, often controlled for balance. "Center of Mass (CoM) task"

- Center of Pressure (CoP): The point on the support surface where the resultant ground reaction force acts; used to maintain balance. "Center of Pressure (CoP)-aware"

- Compliant Motion Augmentation (CMA): An offline process generating feasible, styled compliant trajectories to guide RL training. "Compliant Motion Augmentation provides fine-grained control over compliant style."

- Contact-consistent projections: Projections used in whole-body control to enforce contact constraints while prioritizing tasks. "contact-consistent projections"

- DeepMimic: A reinforcement learning framework for motion imitation from reference trajectories. "DeepMimic"

- Differential inverse kinematics: An IK method that computes small joint changes to achieve desired end-effector velocities or poses. "differential inverse kinematics"

- External wrench: A combined force and torque applied to a robot link. "external wrench"

- Floating base: A model of a robot with an unconstrained root (e.g., a humanoid’s torso) that is not fixed to the ground. "floating base"

- Force field: A simulated mechanism that applies position-dependent forces to a robot to emulate interactions. "a `force field'"

- Forward kinematics: Computing link poses from joint angles and the robot’s kinematic chain. "forward kinematics"

- Gaussian policy exploration: Using Gaussian noise in actions during RL to explore behaviors. "Gaussian policy exploration"

- Hybrid position/force control: A method that simultaneously regulates position in some directions and force in others. "Hybrid position/force control"

- Impedance-like environment: An environment that resists motion like a stiff system where displacement determines force. "an impedance-like environment"

- Impedance strategy: A control approach that regulates forces by commanding poses relative to estimated displacements. "For an impedance strategy"

- Inverse kinematics (IK) solver: An algorithm that computes joint configurations that achieve desired end-effector poses. "inverse kinematics (IK) solver"

- Log-uniform distribution: A sampling distribution uniform in the logarithm of a variable, used to cover orders of magnitude evenly. "log-uniform distribution"

- MuJoCo: A physics engine for simulating articulated bodies and contacts. "MuJoCo"

- Null-space: The set of joint motions that do not affect higher-priority tasks, often used for posture control. "postural null-space"

- Operational-space formulation: A control framework that expresses dynamics and tasks in end-effector/task space. "The operational-space formulation"

- PD controller: A proportional-derivative feedback controller used to track joint position targets with damping. "PD controller"

- Passivity: A system property ensuring energy is not generated, aiding robust and safe physical interaction. "based on passivity"

- Proprioception: Sensing of the robot’s internal states (e.g., joint angles/velocities) without external sensors. "proprioceptive state"

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): A policy gradient RL algorithm known for stable training via clipped objectives. "PPO"

- Quasi-direct-drive (QDD) actuators: Low-gear-ratio torque-controlled motors enabling compliance and force sensing. "quasi-direct-drive (QDD) actuators"

- Retargeted: Adapted human motion data mapped onto a robot’s kinematics. "retargeted using methods"

- Sim-to-real transfer: Techniques for bridging the gap between simulation-trained policies and real-world deployment. "sim-to-real transfer techniques"

- Stiffness adherence: How closely the robot’s effective stiffness matches the commanded value. "Stiffness adherence."

- Task-space error: Deviation measured in Cartesian/task coordinates (e.g., end-effector pose), not joint space. "a task-space error"

- Teleoperation: Human control of a robot in real time, often via motion capture or interfaces. "real-time teleoperation"

- Whole-body operational-space control: A framework coordinating multiple tasks (interaction, posture, balance) on floating-base robots under contact. "Whole-body operational-space control extended this to floating-base systems"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are practical, deployable uses of SoftMimic’s compliant whole‑body control and its compliant motion augmentation (CMA) workflow. Each item lists sector(s), a concrete use case, tools/products/workflows that could be used now, and assumptions/dependencies that affect feasibility.

- Sector: Logistics, Warehousing, E‑commerce

- Use case: Gentle box picking and placement with variable object sizes and mild misalignment using a single reference motion

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Drop‑in whole‑body controller that exposes a “stiffness knob” for Unitree G1‑class humanoids

- CMA toolkit to augment existing MoCap/teleop clips into compliant references per task

- Safety dashboard to monitor peak contact forces in trials and tune stiffness per SKU/category

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- QDD torque‑controlled joints and PD target interface available

- Adequate state estimation; force/pose noise consistent with the paper’s bounds (≈4 N force, ≈1 cm pose)

- Known stiffness range where policies are validated (≈40–1000 N/m translational)

- Sector: Service Robotics, Hospitality, Retail

- Use case: Safe shelf stocking, corridor passing, and tray carrying where hands/forearms may brush fixtures or people

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Operator‑side slider for stiffness modulation depending on crowd density or aisle width

- Pre‑deployment “force‑field test” suite to verify effective stiffness and peak force thresholds in store layouts

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Local safety policies limit allowable contact forces; robot must log commanded/observed stiffness for auditing

- Minimal perception: task completion mainly driven by motion references and compliance, not precise environment models

- Sector: Field Robotics (Facilities, Energy, Industrial inspection)

- Use case: Maneuvering through cluttered plant rooms and pipe racks while maintaining posture but yielding to incidental contacts

- Tools/products/workflows:

- CMA‑generated compliant references for “walk‑through and reach” routines

- On‑site stiffness presets (e.g., very low stiffness near fragile instrumentation)

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Sim‑to‑real transfer validated for your robot morphology; terrain/contact friction matched or robustified

- Sector: Teleoperation and Demonstration Collection (Industry + Academia)

- Use case: Safer teleoperation with tunable compliance to prevent spikes during imperfect demonstrations; higher‑quality datasets for visuomotor learning

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Teleop UI exposing stiffness control

- Logging pipeline that stores original reference, augmented compliant targets, and realized trajectories for downstream imitation

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Existing teleop stack integrated with whole‑body controller and PD target interface

- Operator training on stiffness selection

- Sector: Education and Research

- Use case: Teaching and benchmarking compliant whole‑body control (WBC) that reconciles posture tracking and force interaction

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Course/lab materials using the CMA pipeline (e.g., Mink + MuJoCo) with PPO training (e.g., IsaacLab + rsl_rl)

- Assignments exploring different IK cost hierarchies to shape compliant “styles”

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to motion datasets (AMASS/LAFAN1) and a simulated humanoid with similar kinematics

- Sector: Safety Engineering and Pre‑Certification

- Use case: Internal safety qualification via “effective stiffness adherence” tests and contact‑force envelopes before public pilots

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Force‑field test harness to measure force–displacement ratios at different commands and links (hands, forearms)

- Automated scenario tests: wall brush, corner clip, misplaced box

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Instrumented test fixtures; procedures to bound force impulses and reset episodes using augmented references

- Sector: Home Assistance (near‑term pilots)

- Use case: Basic household manipulation (e.g., moving boxes, opening drawers, pouring) with reduced risk of damaging furniture or belongings

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Small library of compliant motion clips with CMA augmentation for common chores

- User‑friendly stiffness presets (gentle, normal, firm)

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Limited reliance on perception; safe performance achieved primarily via compliance and robust posture control

Long‑Term Applications

These applications likely require further research and system integration (e.g., improved perception, tactile sensing, broader motion libraries, multi‑contact augmentation) or scaling to new domains.

- Sector: Healthcare, Eldercare, Rehabilitation

- Use case: Patient transfer, assisted dressing, and gentle handovers with dynamically scheduled stiffness based on patient fragility and intent

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Compliant WBC integrated with vision/EMG/intent estimation to adapt stiffness on‑the‑fly

- Tactile skin arrays and high‑fidelity force estimation to broaden feasible stiffness range

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Medical‑grade safety certification, redundant safety monitors, robust perception for human pose and intent; extensive validation beyond current stiffness bounds

- Sector: Collaborative Manufacturing and Assembly

- Use case: Close‑proximity human–robot collaboration on variable‑geometry assemblies without detailed part‑specific motion retargeting

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Foundation compliant WBC trained over large motion datasets and CMA across many links and tools

- Scheduling policy that maps perception (object mass, fit tolerance) to stiffness profiles per assembly phase

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Multi‑contact CMA (hands, torso, legs), dynamic contact‑switch planning in augmentation, and reliability under high load

- Sector: Domestic General‑Purpose Humanoids

- Use case: Robust household assistance (laundry, tidying, cooking prep) in unseen homes with safe incidental contacts

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Vision‑language policy that selects both motion references and stiffness settings; compliance‑aware visuomotor policies

- “Compliance style” libraries that can be user‑selected (e.g., bend‑vs‑squat styles)

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Strong perception for task selection, learning‑based stiffness scheduling, and broader motion coverage than single‑clip policies

- Sector: Construction and Field Services

- Use case: Handling bulky/uncertain loads and navigating irregular structures; dynamic trade‑off between stability and yielding

- Tools/products/workflows:

- CMA extended to allow foot re‑placement/contact switching and multi‑link perturbations

- Digital twins for compliance‑aware task rehearsal and hazard analysis

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- More physically faithful augmentation (dynamics‑in‑the‑loop), real‑time replanning, and robust terrain interaction

- Sector: Policy, Standards, and Certification

- Use case: Standards for “effective stiffness adherence” and force envelopes in human–robot interaction; certification protocols using force‑field tests

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Test suites specifying commandable stiffness ranges, link‑wise validation (not only wrists), and pass/fail thresholds for peak forces and impulses

- Logging requirements for commanded stiffness and measured interaction forces during operation

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Consensus across industry bodies (e.g., ISO/ANSI/OSHA) and alignment with diverse robot morphologies and actuator technologies

- Sector: Software, Tooling, and Developer Ecosystem

- Use case: SoftMimic SDKs integrated with ROS 2/Isaac for CMA generation, training, evaluation, and deployment on diverse humanoids

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Turnkey pipelines: MoCap/teleop ingestion → CMA with IK → PPO training → stiffness adherence testing → on‑robot deployment

- Model hubs of “compliance‑ready” policies and motion packs; auto‑retargeters across robot morphologies

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Vendor‑agnostic interfaces to low‑level PD/torque control and standardized description formats for kinematics/dynamics

- Sector: HRI, Social/Service Robotics

- Use case: Safe, comfortable physical interaction (guiding, handshakes, assisting posture changes) where humans set a “comfort stiffness”

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Multimodal feedback (vision, audio, touch) to adapt compliance in real time; user profiles for preferred interaction forces

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- High‑density tactile sensing and robust human intent recognition to expand beyond hand‑only interactions

- Sector: Research Frontiers (Academia + Industry)

- Use case: Foundation compliant whole‑body controllers trained on large motion corpora; learning stiffness scheduling and “style” from data

- Tools/products/workflows:

- CMA with dynamics‑aware objectives; data‑driven distance metrics to resolve nullspace behaviors; multi‑link and whole‑body contact augmentation

- Benchmarks for compliance under partial observability, sensor noise, and multi‑contact

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Significant compute and data, standardized benchmarks, cross‑lab reproducibility, and shared datasets with compliant annotations

Cross‑cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Hardware: Torque‑capable actuators (QDD or equivalent), reliable proprioception; some tasks benefit from tactile skins to broaden stiffness range and link coverage.

- Estimation: Feasible stiffness range is bounded by noise in force and pose estimation; achieving very low or very high stiffness may require better sensing and observers.

- Data: Access to motion references (MoCap or teleop); CMA quality improves with better IK models and, long‑term, dynamics‑aware augmentation.

- Safety: Force/impulse monitoring, software torque limits, and conservative defaults for public deployments.

- Integration: Sim‑to‑real pipelines (e.g., IsaacLab + rsl_rl), robot‑specific retargeting, ROS 2 or equivalent middleware for deployment.

- Governance: For public and healthcare use, adherence to emerging standards for physical HRI and auditable logs of commanded vs. measured interaction forces.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.