- The paper introduces an end-to-end reinforcement learning framework that integrates a learned ball trajectory predictor for proactive table tennis returns.

- The approach uses dense, physics-based reward shaping and residual joint displacements to foster dynamic, coordinated whole-body movements.

- Evaluations in simulation and zero-shot Sim2Real demonstrated high hit rates and effective adaptation to various serve conditions on a 23-DoF humanoid.

Unified Reinforcement Learning with Prediction Augmentation for Humanoid Table Tennis

Introduction

This work addresses the challenge of enabling a high-DoF humanoid robot to play table tennis with versatile, coordinated whole-body motions. Unlike prior approaches that rely on modular pipelines or restrictive assumptions such as the virtual hitting plane, the proposed method formulates the problem as an end-to-end RL task, mapping ball and proprioceptive observations directly to joint commands for both striking and locomotion. The framework is augmented with a learned ball trajectory predictor and dense, physics-informed reward functions, facilitating proactive behavior and efficient policy learning. The resulting policy demonstrates high success rates in simulation and robust zero-shot transfer to a physical 23-DoF humanoid, achieving rapid, coordinated returns across a wide range of serve conditions.

Figure 1: The Booster T1 humanoid successfully returns a high-speed ball (6 m/s) from a serving machine, demonstrating rapid interception and coordinated hand-leg movements.

Methodology

The control problem is cast as a POMDP, where the agent receives partial observations comprising proprioceptive states and ball positions, and outputs reference joint trajectories. The RL objective is to maximize the expected discounted return, with the policy πθ mapping observation histories to actions. The action space is defined as residual joint displacements from a nominal pose, promoting stable and efficient learning.

Predictor-Augmented Policy Architecture

A key innovation is the integration of a lightweight, learnable ball trajectory predictor into the policy pipeline. The predictor, trained online using simulated ball trajectories and physics-based ground truth, estimates the future apex of the incoming ball after its first bounce. This prediction is used to compute a target base shift, Δp~base,xy, representing the required horizontal displacement for optimal interception.

The actor network receives both the predicted ball apex and the base shift as part of its observation, enabling proactive movement. The critic, in contrast, is provided with privileged, noise-free simulation data, including ground-truth ball trajectories and velocities, to facilitate accurate value estimation during training.

Figure 2: Overview of the training pipeline, showing the integration of the learnable predictor and the use of physics-based simulation for reward shaping and privileged critic information.

Prediction-Based Reward Design

Sparse binary rewards (e.g., successful hit or return) are insufficient for efficient policy learning in this high-dimensional, fast-paced task. Instead, the reward function is densely shaped using physics-based predictions:

- Reaching Reward: Penalizes the distance between the end-effector and the predicted hitting point, as well as the discrepancy between the robot's base position and the optimal interception location.

- Velocity Reward: Penalizes mismatch between the robot's base velocity and a pseudo-velocity command derived from the predicted ball trajectory.

- Returning Reward: After each strike, penalizes the distance between the predicted landing point of the ball and the target region on the opponent's table, and encourages the ball to clear the net with a specified margin.

This reward structure provides immediate, informative feedback, accelerating the acquisition of both striking and locomotion skills.

Figure 3: Prediction-based reward design, illustrating the use of anticipated ball trajectories for both hit-guidance and return-guidance rewards.

Observation and Action Spaces

The actor's observation includes a history of proprioceptive and exteroceptive signals, predicted ball apex, and base shift. The critic receives additional privileged information available only in simulation. The action space consists of 21 joint displacement commands, added to a nominal standing pose, and tracked by a low-level PD controller.

Training and Experimental Setup

Simulation

Training is conducted in IsaacLab via the LeggedLab framework, with 4096 parallel environments and domain randomization applied to physical parameters and perception noise. Aerodynamic drag is modeled using a quadratic-in-speed force, calibrated from real-world ball trajectories. Each episode consists of up to five consecutive serves with randomized initial conditions, promoting exploration of diverse footwork and striking strategies.

The actor and critic are implemented as MLPs with [512, 512, 128] hidden units, optimized using PPO. The predictor is a two-layer MLP ([64, 64]), trained online with RMSE loss against physics-based apex predictions.

Hardware

The Booster T1 humanoid (23 DoF, 1.2 m, 30 kg) is equipped with a custom paddle mount and tracked via a Vicon motion capture system (5 mm accuracy at 150 Hz). The robot is evaluated on a standard table tennis table, with a ball-serving machine providing randomized serves within the training distribution.

Results

The policy achieves high hit and return rates across a range of serve types and velocities:

| Serve Type |

Hit Rate |

Success Rate |

Total Serves |

| Long |

96.1% |

92.3% |

42,181 |

| Mid-long |

97.0% |

95.0% |

41,390 |

| Short |

99.3% |

94.8% |

92,601 |

| Mixed |

97.6% |

94.1% |

88,016 |

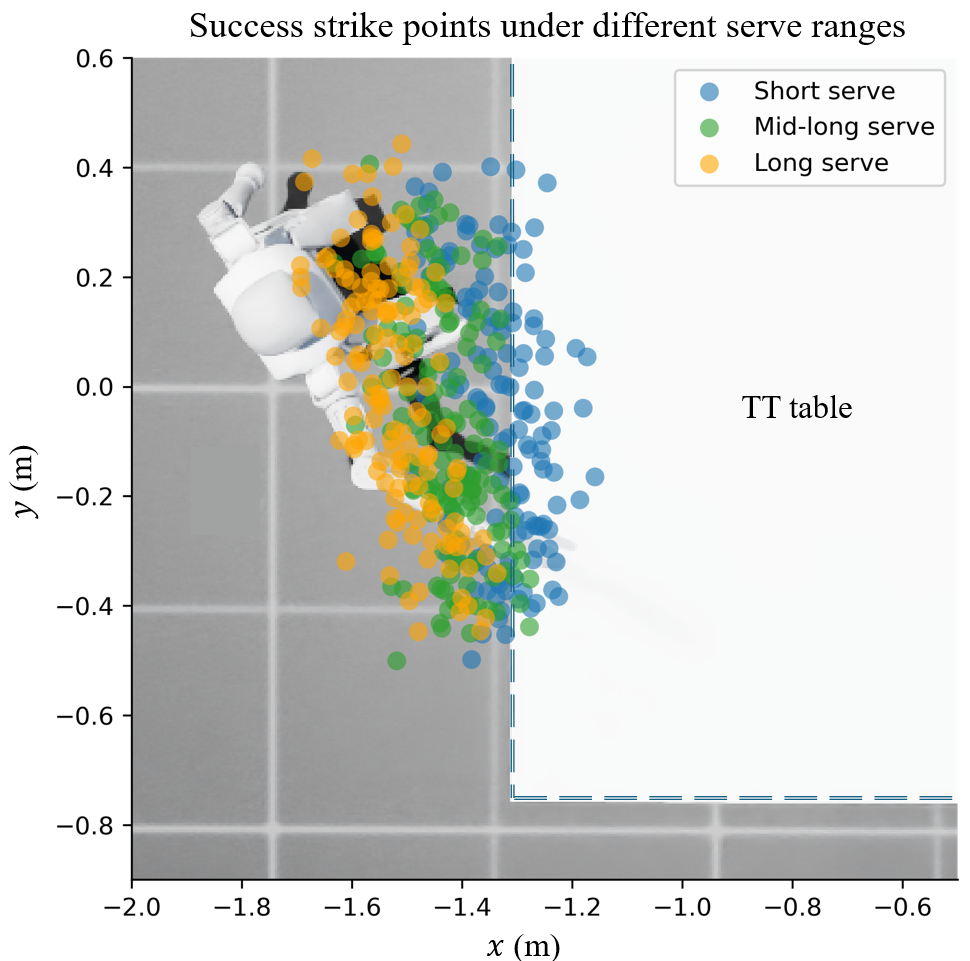

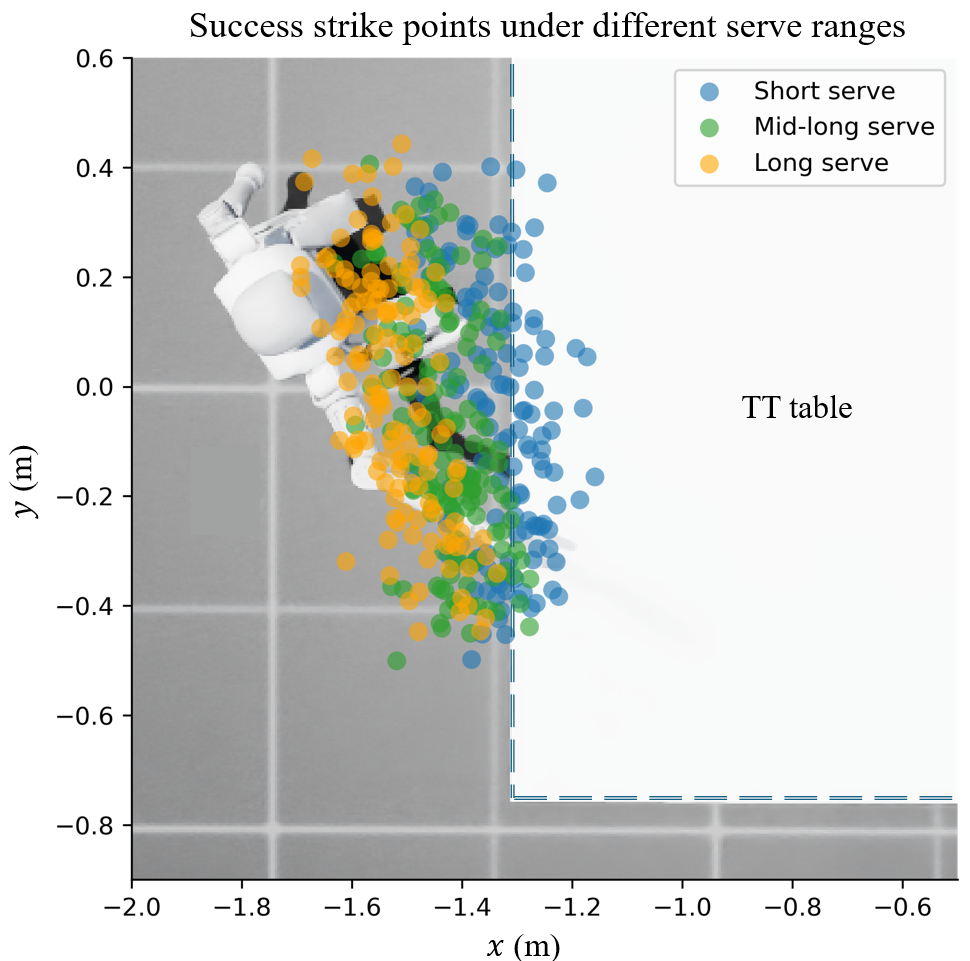

The policy generalizes to both short and long serves, requiring dynamic forward-backward and lateral footwork. The distribution of successful strike points demonstrates that the policy does not rely on a fixed hitting plane, but instead adapts its interception strategy to the incoming trajectory.

Figure 4: Success strike positions under different serve ranges, illustrating the policy's adaptation to diverse ball trajectories.

Emergent Whole-Body Coordination

Time-lapse sequences and footwork analysis reveal the emergence of coordinated arm, trunk, and leg movements. The policy produces both lateral and forward-backward footwork, with the robot dynamically adjusting its stance and trunk rotation in response to serve direction and speed.

Figure 5: Time-lapse sequences of two consecutive rallies, showing variation in arm and trunk usage for different ball trajectories.

Figure 6: Dynamic 2-D footwork before ball strike, with arrows indicating the movement directions of the robot's feet and trunk.

Ablation Studies

Ablation experiments confirm the necessity of both the predictor and the prediction-based reward design. Removing the predictor from the actor's observation leads to a sharp decline in both hit and return rates, as the policy fails to move proactively. Eliminating dense reward terms results in poor exploration and failure to learn effective striking or returning behaviors.

Figure 7: Ablation study showing the impact of removing the predictor and prediction-based rewards on training performance.

Sim2Real Transfer

Zero-shot deployment on the Booster T1 yields a hit rate of 93.5% and a return success rate of 61.3% over 31 trials, with the mean outbound ball speed (6.9 m/s) exceeding the incoming speed. The observed Sim2Real gap is attributed to unmodeled actuation dynamics, contact discrepancies, and the limited DoF of the robot's arm. Nevertheless, the policy demonstrates robust, versatile whole-body coordination, including emergent forward-backward footwork and rapid recovery between rallies.

Implications and Future Directions

This work demonstrates that unified, end-to-end RL with prediction augmentation can enable high-DoF humanoids to perform complex, dynamic tasks requiring rapid perception, proactive planning, and whole-body coordination. The dense, physics-informed reward design and predictor-augmented policy architecture are critical for overcoming the challenges of sparse rewards and high-dimensional action spaces.

The results suggest several avenues for future research:

- Enhanced Dexterity: Incorporating higher-DoF arms and wrists to enable a broader repertoire of strokes, including backhand and spin-based maneuvers.

- Imitation and Curriculum Learning: Leveraging human demonstration data and curriculum strategies to accelerate skill acquisition and improve generalization.

- Robustness to Real-World Variability: Further reducing the Sim2Real gap via improved actuation models, contact dynamics, and adaptive perception.

- Multi-Agent and Competitive Play: Extending the framework to adversarial or cooperative multi-agent settings, enabling humanoids to engage in rallies with human or robotic opponents.

Conclusion

The proposed unified RL framework with prediction augmentation achieves high-performance, versatile table tennis play on a 23-DoF humanoid, both in simulation and hardware. The integration of a learned predictor and dense, physics-based rewards is essential for enabling proactive, coordinated whole-body behaviors. This approach provides a scalable foundation for future research in dynamic, high-DoF robotic sports and other domains requiring rapid, adaptive whole-body control.