Measuring pulse heating in Si quantum dots with individual two-level fluctuators

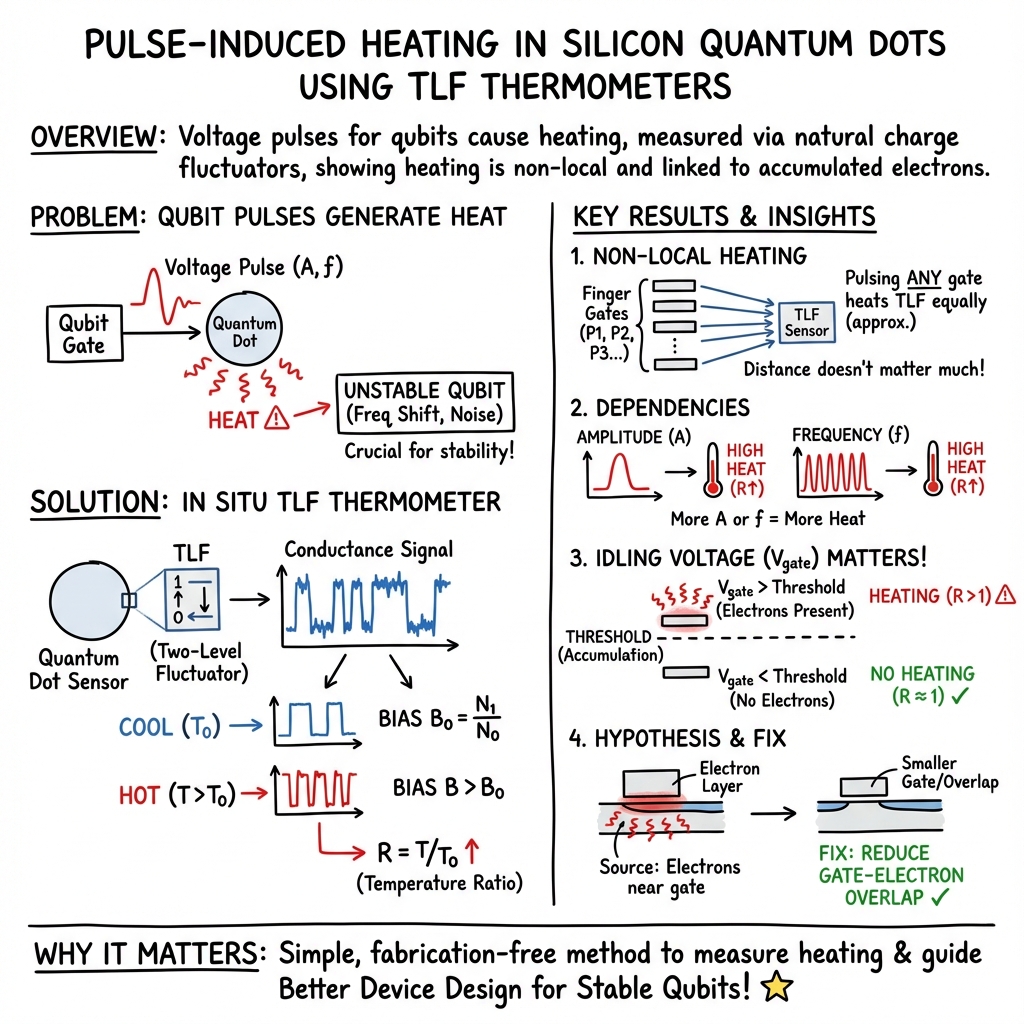

Abstract: To encode quantum information in semiconductor spin qubits, voltage pulses are necessary for initialization, gate operation, and readout. However, these pulses dissipate heat, shifting spin-qubit frequencies and reducing gate fidelities. The cause of this pulse heating in quantum-dot devices is unknown. Here, we measure pulse heating using charged two-level fluctuators (TLFs) in Si/SiGe quantum dots. We find that the TLFs are susceptible to pulse heating. The amount of heating depends on the pulse amplitude and frequency, but not on the distance between the pulsed gates and the TLFs. The amount of heating also generally depends on the idling voltage of the pulsed gates, suggesting that electrons accumulated under or near the gates contribute to the heating. We hypothesize that reducing the area of the gates with electrons nearby could mitigate the heating.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper studies a problem in tiny, silicon-based quantum devices called quantum dots. These devices use the spin of electrons as “qubits” to store and process quantum information. To control qubits, researchers send quick voltage pulses to metal gates on the chip. But these pulses can create extra heat, which can mess up the qubits by shifting their operating frequencies and lowering the accuracy of their gates. The paper’s main idea is to use naturally occurring “two-level fluctuators” (TLFs)—tiny defects that behave like little switches—to detect and measure this pulse-induced heating inside the device, without needing to build a separate thermometer.

What questions are the researchers trying to answer?

In simple terms, they asked:

- Do the voltage pulses used to control qubits heat up parts of the device?

- How does that heating depend on the strength (amplitude) and speed (frequency) of the pulses?

- Does the heating depend on how close the pulsed gate is to the tiny defect (the TLF)?

- Does the heating depend on the “idling voltage” of the gate (the voltage you set and leave in place when you’re not actively pulsing)?

- What might be causing the heating, and how could we reduce it?

How did they do the experiment?

Think of the device like a neighborhood of tiny electron “islands” (quantum dots) controlled by metal “gates” (like electrical fences). The team looked at a special kind of defect near one of these islands—a two-level fluctuator (TLF). A TLF is a tiny object that can be in one of two states and randomly flips between them, a bit like a small switch that goes “on” and “off.” Importantly, TLFs flip faster when they get warmer, which makes them useful as built-in thermometers.

Here’s the basic approach, explained in everyday terms:

- They applied sinusoidal voltage pulses (smooth up-and-down signals) to different gates to generate heat.

- They measured how a nearby TLF behaved using a “charge sensor” quantum dot and radio-frequency signals. This is called rf reflectometry—imagine using a soft “ping” to feel how easily electrons can move, which changes when the TLF flips.

- Because they didn’t have a direct thermometer, they looked at how often the TLF was in its lower-energy state versus its higher-energy state. When things get hotter, the TLF spends relatively more time in the higher-energy state and flips faster. From that ratio, they estimated how much the temperature increased.

Helpful analogies for key terms:

- Quantum dot: A tiny trap that can hold electrons, like a small bowl holding marbles.

- Spin qubit: Using an electron’s spin (like a mini compass pointing up or down) as a quantum bit.

- Gate: A metal “control knob” that shapes where electrons can go.

- Voltage pulse: A quick change in the control knob to make things happen fast.

- Two-level fluctuator (TLF): A tiny defect acting like a coin that randomly flips between heads and tails; it flips faster when warmed.

- Idling voltage: The gate’s “resting” setting between pulses.

- Accumulation threshold: The minimum gate voltage needed for electrons to gather under the gate. Above this threshold, electrons collect; below it, they don’t.

They summarized heating using a “temperature ratio” R, which compares the effective TLF temperature during pulsing to the temperature without pulsing. They assumed the energy difference between the TLF’s two states stayed the same while they changed the pulses, which they cross-checked in the device.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

The researchers found several clear patterns. Here are the main results:

- Heating happens when gates are pulsed: The TLF flipped faster and shifted its state balance in a way that shows it got warmer during pulses.

- Stronger and faster pulses cause more heating: Increasing the pulse amplitude or the pulse frequency increased the measured temperature ratio.

- The heating is not strongly tied to distance: Pulsing gates farther from the TLF produced similar heating to pulsing nearby gates. This suggests the heat spreads through the device rather than affecting only a tiny local spot.

- The idling voltage matters a lot: When a gate’s idling voltage was below the accumulation threshold (so no electrons sat under or near the gate), the heating was greatly reduced or nearly gone. When the idling voltage was above the threshold (electrons present), heating increased.

- Even pulsing a “screening” gate (meant to block or shape fields) caused noticeable heating if there were electrons near it under neighboring gates.

Why this is important:

- Heat changes qubit frequencies and can add noise, which reduces how well quantum gates work. Understanding where and why heating happens helps make more reliable quantum chips.

- Using TLFs as “built-in thermometers” is clever because it requires no extra parts or complicated fabrication steps.

What does this mean for the future?

This work points to a practical way to reduce pulse heating:

- Since heating seems linked to electrons sitting under or near gates, redesigning the chip so fewer electrons collect near pulsed gates could help. For example, shrinking the overlap between gates and the electron layer, or moving neighboring accumulation gates farther away from pulsed gates.

- Longer-term, using vertical connections (vias) to place metal control lines farther from the sensitive semiconductor layers might also reduce heating.

The paper also raises an open question: how exactly does this heating connect to the observed shifts in qubit frequency during pulses? The authors’ results show that electrical defects like TLFs are affected by heating, which supports theories that temperature changes influence qubit behavior. Future work could use TLFs as local, on-chip thermometers to map temperature during fast gate operations and guide better device designs.

In short: the team showed that voltage pulses can heat silicon quantum-dot devices in ways that depend on pulse settings and gate voltages—especially whether electrons sit under the gates—and they offered clear ideas to reduce that heating, helping move toward more stable and accurate quantum processors.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.