Generative Medical Event Models Improve with Scale (2508.12104v1)

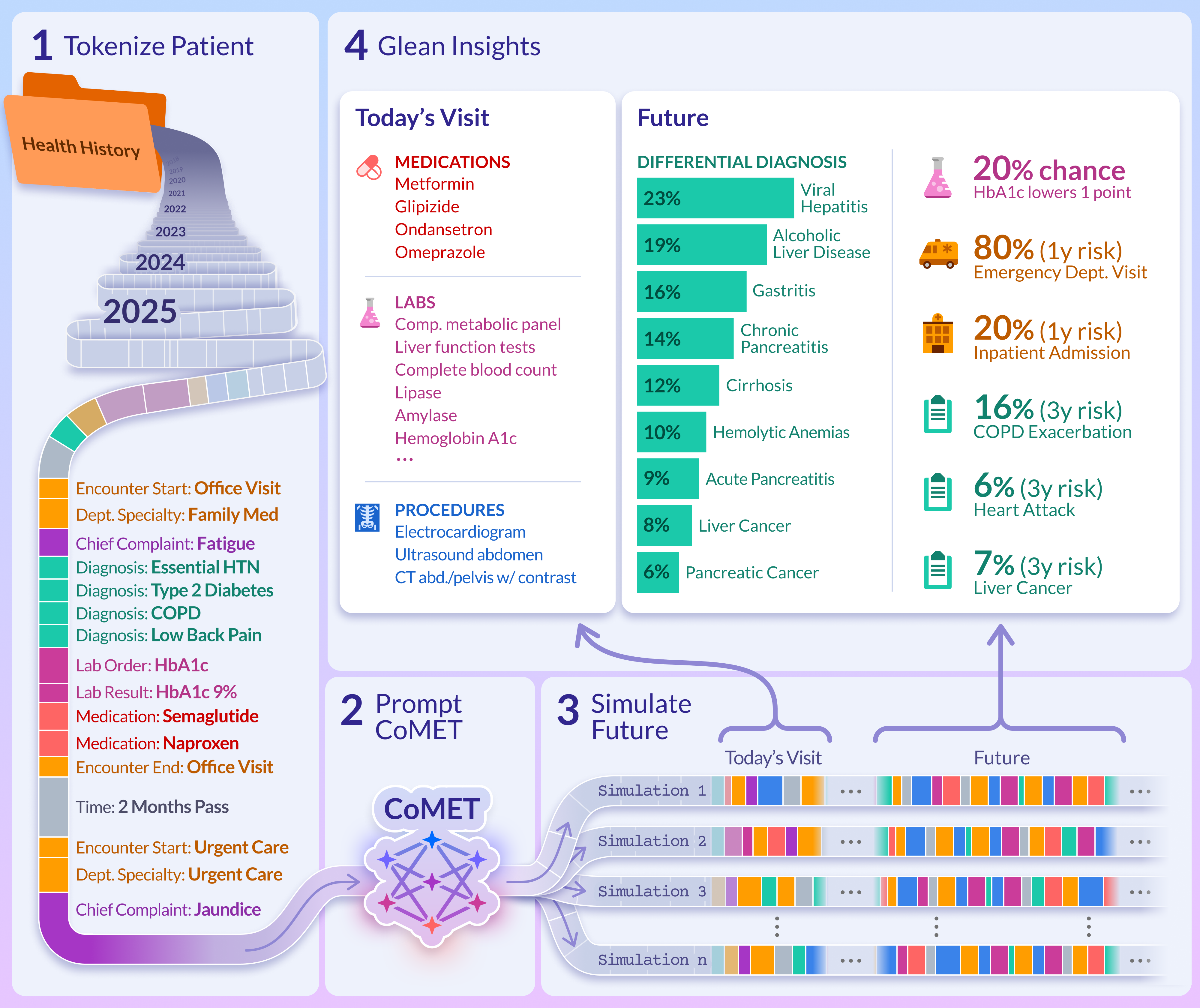

Abstract: Realizing personalized medicine at scale calls for methods that distill insights from longitudinal patient journeys, which can be viewed as a sequence of medical events. Foundation models pretrained on large-scale medical event data represent a promising direction for scaling real-world evidence generation and generalizing to diverse downstream tasks. Using Epic Cosmos, a dataset with medical events from de-identified longitudinal health records for 16.3 billion encounters over 300 million unique patient records from 310 health systems, we introduce the Cosmos Medical Event Transformer ( CoMET) models, a family of decoder-only transformer models pretrained on 118 million patients representing 115 billion discrete medical events (151 billion tokens). We present the largest scaling-law study for medical event data, establishing a methodology for pretraining and revealing power-law scaling relationships for compute, tokens, and model size. Based on this, we pretrained a series of compute-optimal models with up to 1 billion parameters. Conditioned on a patient's real-world history, CoMET autoregressively generates the next medical event, simulating patient health timelines. We studied 78 real-world tasks, including diagnosis prediction, disease prognosis, and healthcare operations. Remarkably for a foundation model with generic pretraining and simulation-based inference, CoMET generally outperformed or matched task-specific supervised models on these tasks, without requiring task-specific fine-tuning or few-shot examples. CoMET's predictive power consistently improves as the model and pretraining scale. Our results show that CoMET, a generative medical event foundation model, can effectively capture complex clinical dynamics, providing an extensible and generalizable framework to support clinical decision-making, streamline healthcare operations, and improve patient outcomes.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces CoMET, a computer model that learns from millions of patient health records to predict what might happen next in someone’s medical journey. Think of a patient’s record like a timeline or diary of “events” (doctor visits, tests, diagnoses, medicines, etc.). CoMET studies lots of these timelines and learns to continue them—one event at a time—so it can estimate risks (like “What’s the chance of a stroke in the next year?”), plan care, and help hospitals prepare resources. The big idea: as these models get bigger and train on more data, they get better in a predictable way.

What questions did the researchers ask?

They focused on four simple questions:

- Can one general-purpose model, trained on many patient histories, make accurate predictions for many different medical tasks without being re-trained for each one?

- Do bigger models trained on more data work better, and is there a rule of thumb for how to scale them?

- Are the event sequences the model generates realistic (do they look like real life)?

- How does this general model compare with specialized models built just for one task?

How did they do it?

They used de-identified records from Epic Cosmos, a very large collection of real-world medical data (over 300 million patients and 16+ billion encounters). From this, they trained CoMET on 118 million patients with 115 billion medical events.

Here’s the approach, in everyday terms:

- Turning records into timelines: Each patient’s history was ordered in time. Every item—like a diagnosis code or a lab test—was converted into a tiny shorthand “token,” so a whole history became a long sequence of tokens (like letters forming words and sentences).

- Learning by predicting the “next step”: CoMET is a type of AI called a transformer. Like a good text predictor that guesses the next word, CoMET guesses the next medical event in a patient’s timeline. By doing this millions of times, it learns patterns of care and disease.

- Simulating the future: To make predictions, CoMET reads a patient’s past and then “plays out” many possible futures, one event at a time. From these simulations, it calculates things like “How likely is a hospital readmission in 30 days?” or “How many clinic visits might happen next year?”

- Testing on many tasks: They checked CoMET’s skills on 78 real-world tasks, including disease risk (e.g., diabetes complications), early diagnosis, and hospital operations (like length of stay). They compared CoMET to strong “specialist” models built just for each task (like logistic regression, XGBoost, and task-specific transformers).

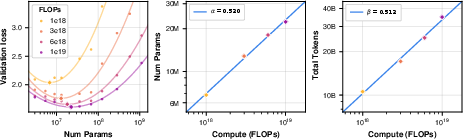

- Finding scaling rules: They ran a big paper to find “scaling laws”—simple rules that tell you how to choose the best model size and training data amount for a given compute budget. This helps avoid wasting time and money.

What did they find, and why is it important?

Overall, CoMET’s predictions were realistic and often as good as—or better than—specialized models, especially as CoMET got larger. Key takeaways include:

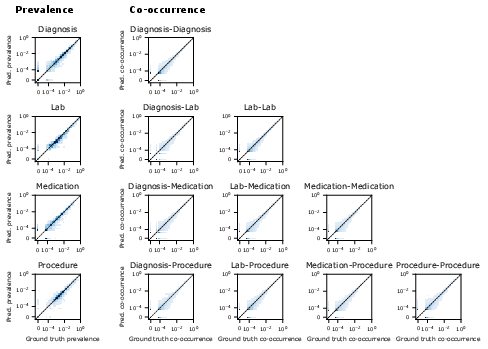

- Realistic generated timelines:

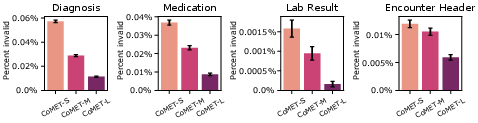

- The model’s made-up sequences looked like real data: the rates of diagnoses, meds, labs, and their combinations matched reality well.

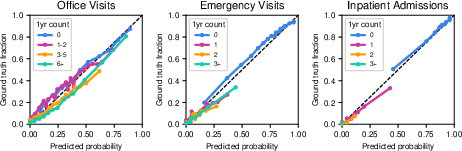

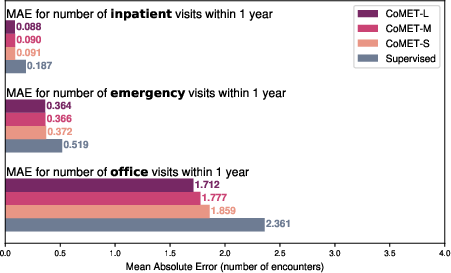

- It was well-calibrated at predicting how many office, emergency, or hospital visits a patient might have in the next year.

- Better single-visit predictions:

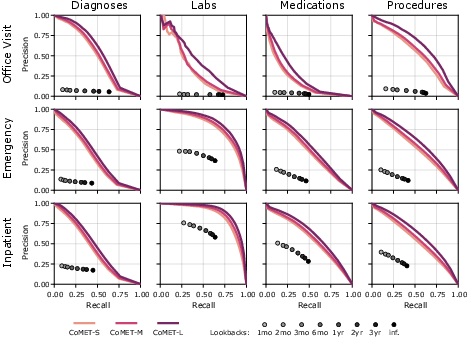

- For a given visit (like an ER trip), CoMET did a better job than simple “look back at prior history” methods at predicting which diagnoses, labs, procedures, and meds would occur during that visit.

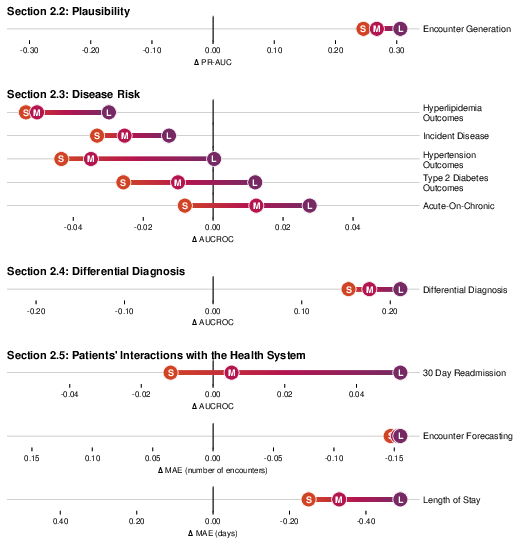

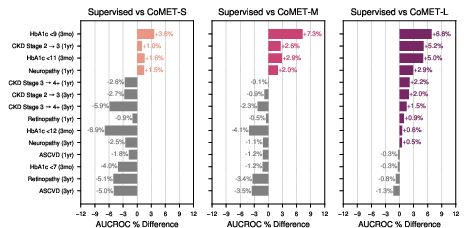

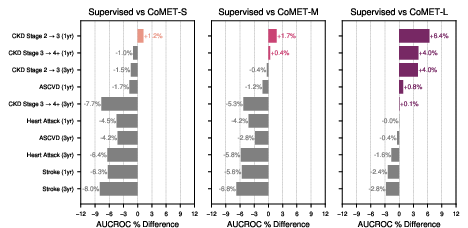

- Strong disease risk prediction:

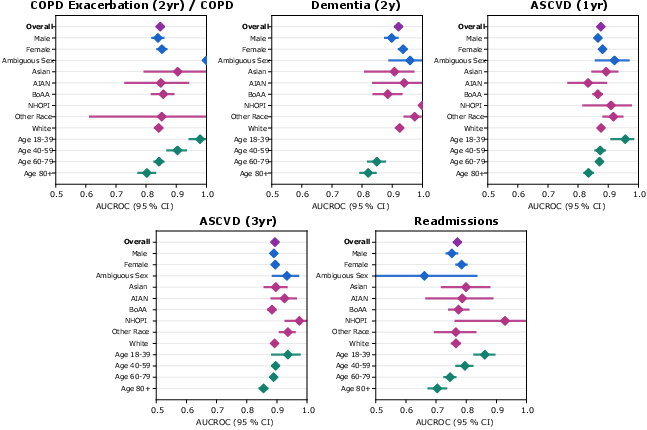

- For patients with conditions like type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure, CoMET often matched or beat specialized models at predicting future problems (like heart disease, kidney disease progression, or stroke).

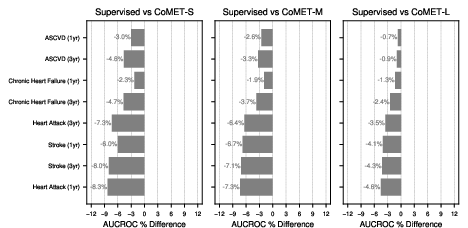

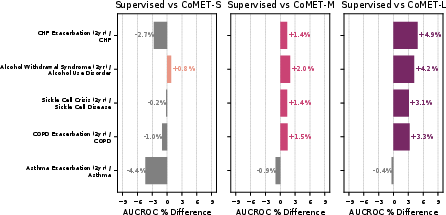

- For “acute-on-chronic” events (like asthma attacks in people with asthma), the biggest CoMET model usually did best.

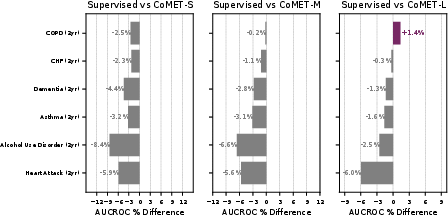

- For detecting brand-new diseases in the general population (where positives are very rare), CoMET sometimes didn’t win on one metric (AUCROC), but it did better on another important metric for rare events (PR-AUC). Using more simulated futures per patient improved results.

- Early, ranked differential diagnosis:

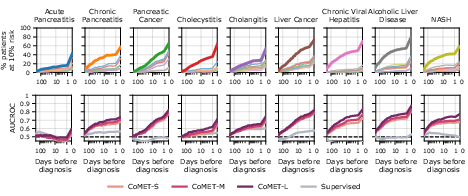

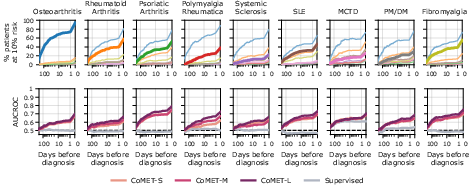

- CoMET could provide a ranked list of likely diagnoses (a “differential”) before a final diagnosis was made, especially for complex areas like liver/pancreas/bile diseases and rheumatology. It often flagged the correct diagnosis weeks in advance and became more accurate as more information appeared.

- Hospital operations:

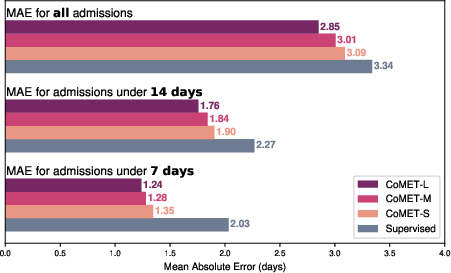

- CoMET predicted the number of future visits more accurately (lower error) than baselines.

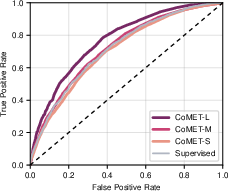

- It predicted hospital length of stay with lower error, and 30-day readmission risk with a higher score (AUC of 0.77 vs. 0.717 for the best baseline).

- Scaling laws and efficiency:

- They found simple, predictable rules: as you increase compute, the best model size and the best amount of training data grow in step. This mirrors findings from language AI.

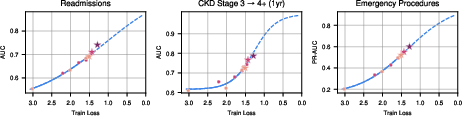

- Training loss (a measure of how well the model fits the data) went down with scale, and as loss went down, real-world performance went up.

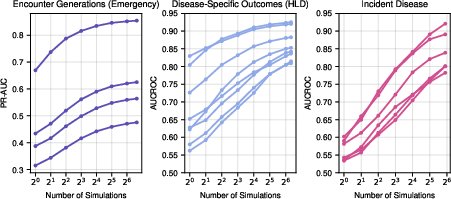

- Generating more simulated futures at test time also improved accuracy, up to a point.

Why this matters: Instead of building a new model for every single clinical question, one well-trained general model can answer many kinds of questions by simulating futures. That could save time, reduce manual work, and help deliver more personalized care.

What could this mean for healthcare?

If carefully validated and used responsibly, a model like CoMET could:

- Help clinicians weigh risks and plan care tailored to each patient (for example, picking treatments based on likely benefits and risks).

- Support earlier, more focused diagnostic workups by highlighting likely conditions sooner.

- Improve hospital planning (beds, staffing) by predicting length of stay and readmissions.

- Make better use of real-world data right at the point of care, without needing to build a new tool for every question.

Important notes:

- This is a decision-support tool, not a replacement for clinicians.

- It was trained on de-identified data and governed within the Cosmos network, but fairness, bias, and safety still need ongoing checks.

- Some tasks were harder than others; more research is needed to understand where and why the model underperforms.

- Future work could include even larger models, more data types (like clinical notes or images), stronger calibration, and prospective clinical studies.

In short, the paper shows that a single, scalable “medical event” model can learn from many patient histories and provide useful, flexible predictions across many healthcare tasks—and it gets better as it grows.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.