- The paper introduces a PDE-based derivation that unifies diffusion models and extends them to address complex probabilistic inverse problems.

- It details forward and reverse processes using variance exploding and variance preserving formulations, incorporating neural network-based score matching.

- Results demonstrate robust applications including conditional density estimation and boundary flux estimation in fluid systems with sparse measurements.

Diffusion Models and Inverse Problems

Introduction

The paper "Unifying and extending Diffusion Models through PDEs for solving Inverse Problems" presents a method for deriving diffusion models using techniques from partial differential equations (PDEs). It reimagines the conventional approach to diffusion models by focusing on probabilistic density functions rather than sample paths. This approach offers several benefits, including clearer derivations of the forward and reverse processes, a unified exposition of different diffusion model variants, and the proposition of new model classes. The paper also explores applications of these models to canonical conditional density estimation and more complex physics-based inverse problems.

Unconditional Diffusion Models

Forward and Reverse Processes

The paper delineates the mathematical framework for diffusion models beginning with the PDE:

∂t∂pt()=2γ(t)Δpt().

The solution utilizes Green's functions, describing how densities evolve from a structured data distribution to a more tractable one, like a Gaussian. Two formulations arise: variance exploding, where the variance grows large over time, and variance preserving, where the variance remains bounded.

The forward process for the variance exploding formulation is established by transforming the data distribution into a wide Gaussian, aiding straightforward sampling. Meanwhile, variance preserving adapts coordinates to contain variance growth, maintaining a closer match to original distributions.

Reverse processes are framed by adapting particle systems for practical sampling (Figure 1), using stochastic differential equations (SDEs), or ordinary differential equations (ODEs), depending on the variance condition set. These processes involve complex velocity fields derived from score functions which are key in evolving samples to their original data structure.

Score Matching

A critical aspect of implementing diffusion models is learning the score function through neural network approximations. The paper reformulates classic Fisher divergence in terms of time-dependent score sequences, allowing training via samples from the target distribution (Figure 2). Denoising score matching modifies objectives to ensure numerical stability.

Probabilistic Inverse Problems

Inverse problems aim to infer underlying parameters from observed data. The paper expresses these problems in terms of conditional probabilities, where known measurement data influences inferred variable distributions. The conditional distribution is approached as a generative function restructured by diffusion processes (Figure 3). Complex forward models and measurement noise become manageable within this framework.

Conditional Diffusion Models

For conditional diffusion models, the paper presents density evolution for conditional distributions adhering to similar PDE structures. The derivation focuses on differentiating diffusion of the inferred variables from measurement variables. Through this model, learning conditional score functions poses rich structures, facilitating posterior sampling without reliance on explicit forward models.

Results and Applications

Conditional Density Estimation

Experiments demonstrate diffusion models' efficacy in recovering conditional distributions from joint distributions, focusing on complex two-dimensional cases that mimic real-world data conditions (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Histograms comparing sample distributions for multiple conditional values, highlighting diffusion model accuracy.

Boundary Flux Estimation in an Advection-Diffusion System

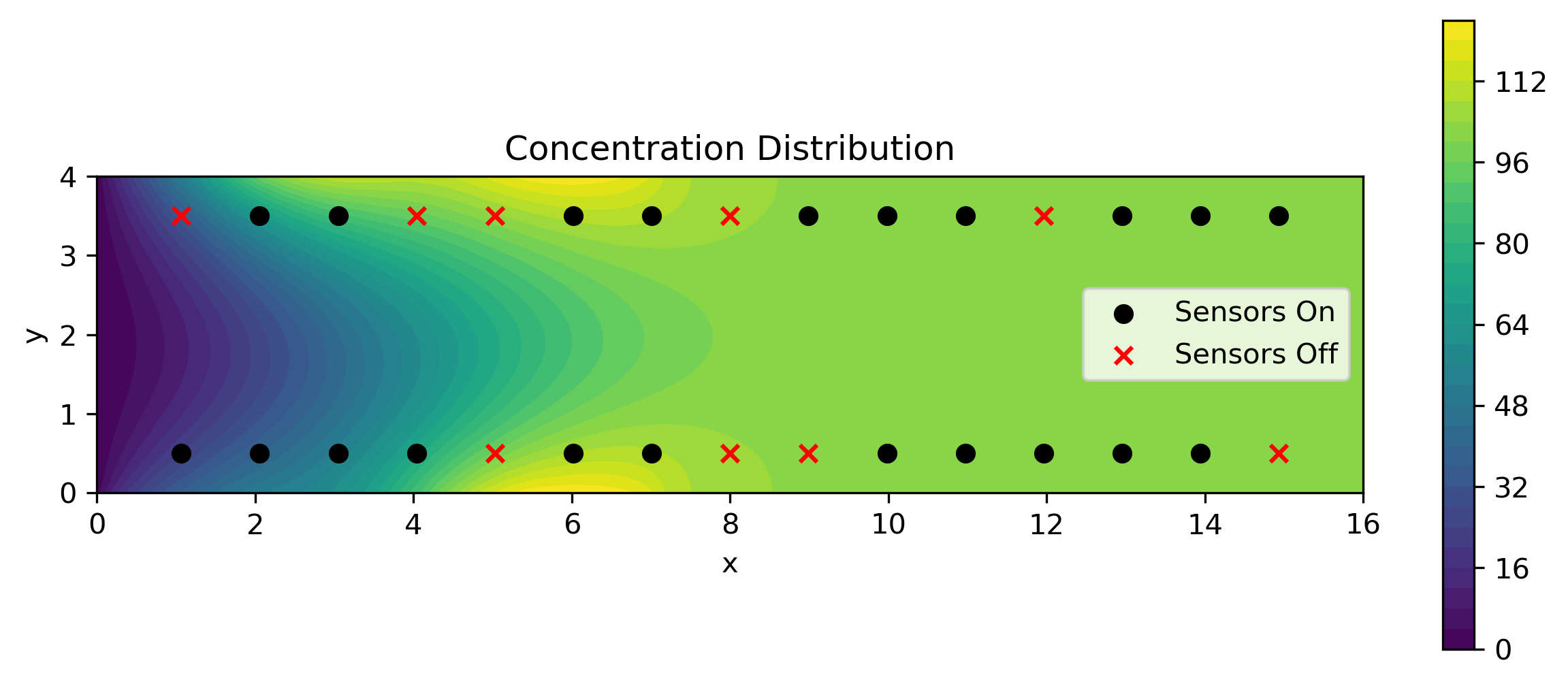

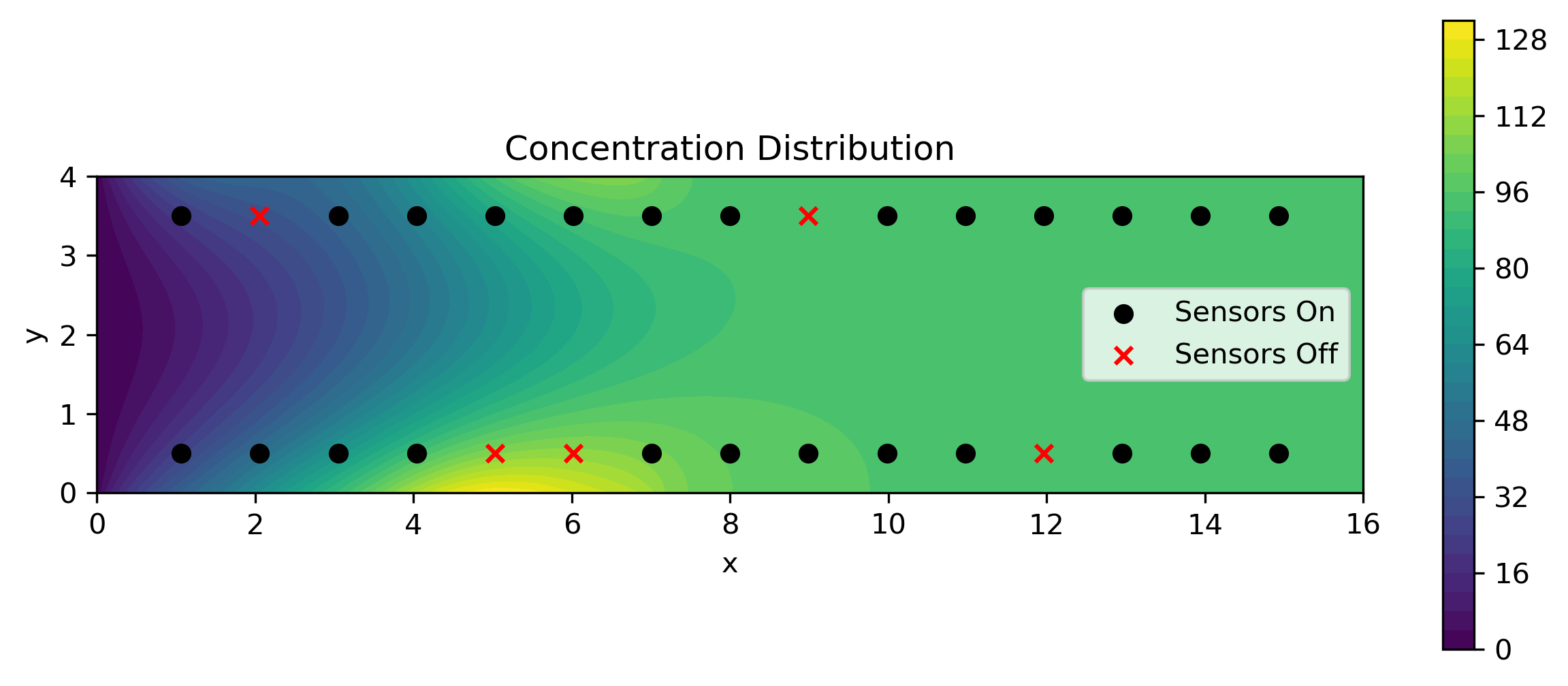

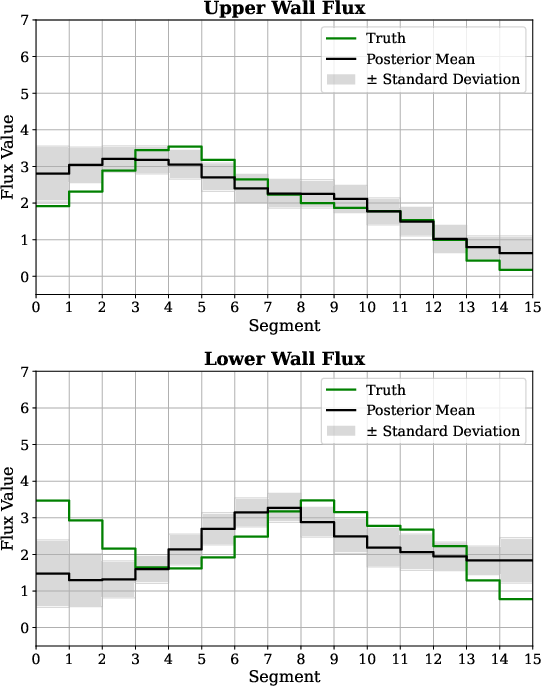

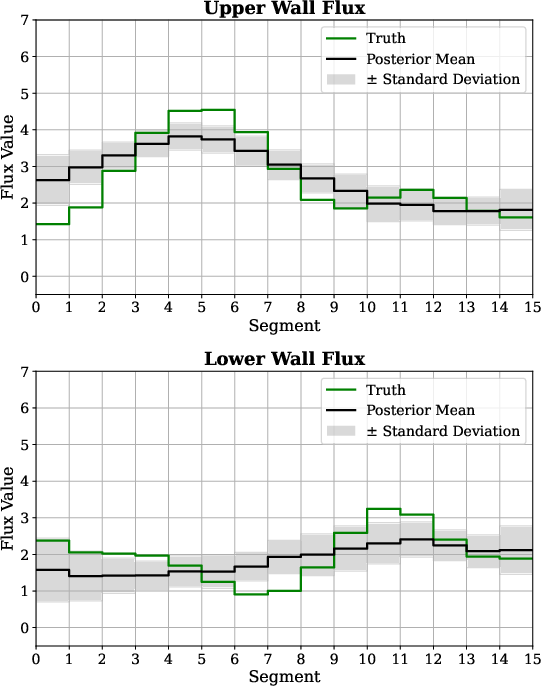

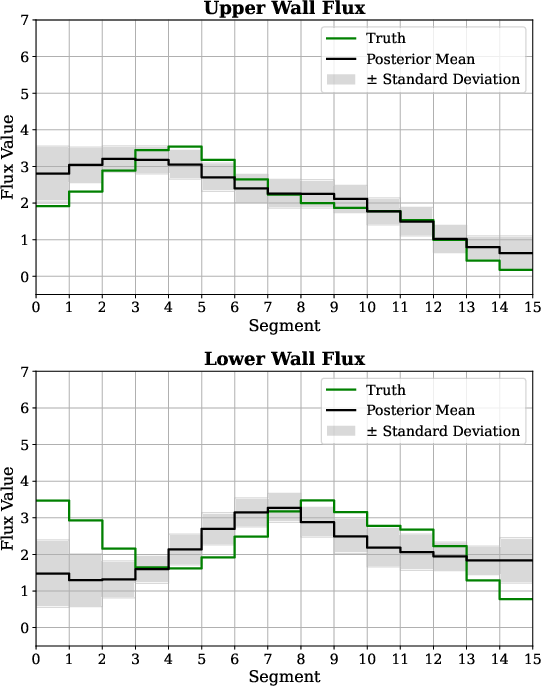

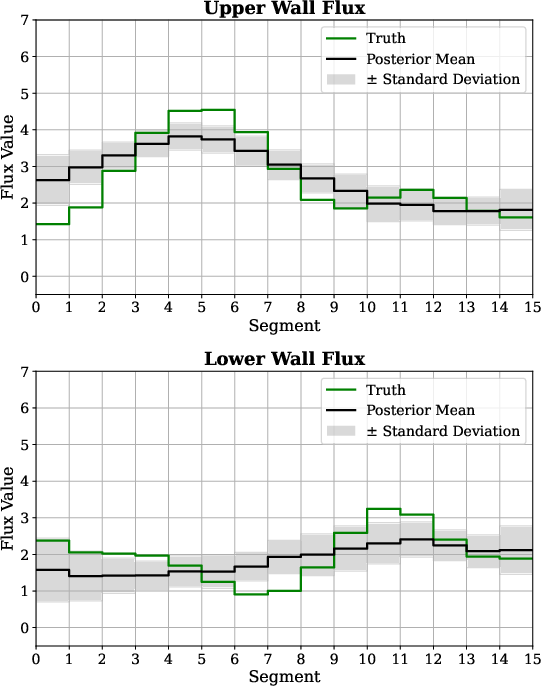

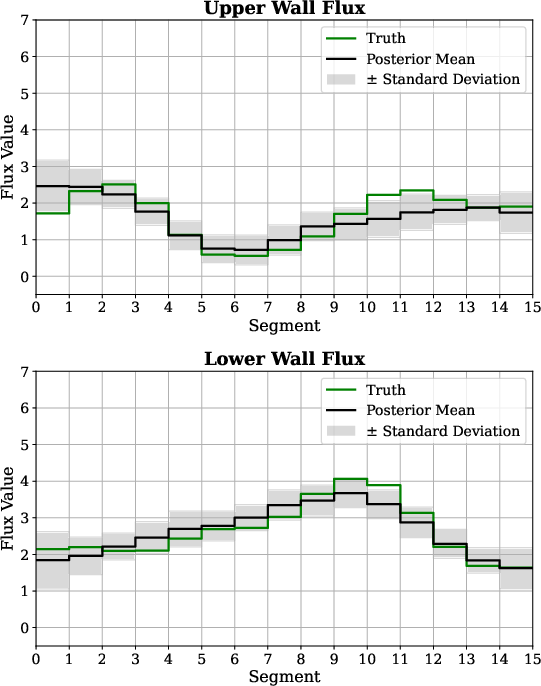

The proposed conditional diffusion models are applied to estimating boundary fluxes in fluid systems using sparse, noisy measurements. The exploration of variance formulations and sampling methods concludes similarity in results but acknowledges that variance-preserving can slightly outperform in specific error metrics (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Posterior mean boundary flux estimation demonstrating model fidelity against true values and measurement variability.

Multi-Measurement Operators

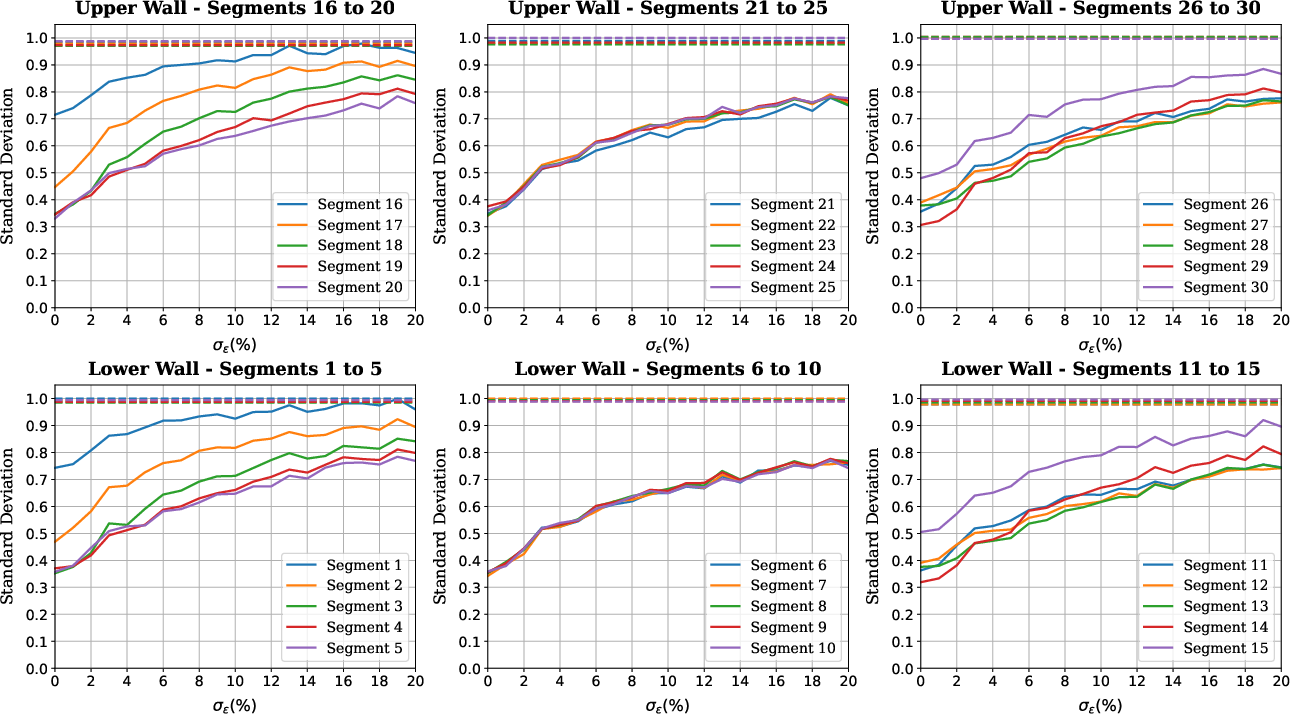

The paper extends applications to multi-measurement operator scenarios, where measurement configurations change randomly. Illustrated examples show how the system accommodates diverse conditions efficiently, adjusting model predictions by embedding measurement parameters in the problem setup (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Influence of measurement noise variability across multiple operator conditions, reinforcing model robustness.

Conclusions

The research provides a novel perspective on diffusion model implementation by leveraging PDE approaches. It enhances understanding while offering adaptable solutions for complex probabilistic inverse problems in science and engineering. Future work will likely explore additional applications across varying physical models and extend model flexibility and scaling capabilities. The integration with advanced neural architectures presents promising enhancements to inverse problem-solving methodologies.