- The paper introduces EPIG, a novel acquisition function that directly targets predictive uncertainty instead of parameter uncertainty like BALD.

- It derives EPIG from Bayesian experimental design, incorporating the target input distribution to focus on relevant predictive tasks.

- Extensive experiments on synthetic, UCI, and MNIST datasets demonstrate EPIG’s superior performance and robustness over BALD.

Prediction-Oriented Bayesian Active Learning

This paper introduces the expected predictive information gain (EPIG) as a novel acquisition function for Bayesian active learning, addressing the limitations of the commonly used Bayesian active learning by disagreement (BALD) score. It highlights how BALD, which maximizes information gain about model parameters, can be suboptimal for predictive performance due to its lack of consideration for the input distribution and potential irrelevance to the predictive task. The authors propose EPIG, which directly targets information gain in predictions, making it a more suitable replacement for BALD in various scenarios.

Background and Motivation

The paper begins by reviewing the principles of active learning and Bayesian experimental design, emphasizing the importance of probabilistic generative models in Bayesian active learning. It highlights that BALD, while widely used, focuses on maximizing information gain in model parameters, which may not always align with the goal of making accurate predictions on unseen inputs. The authors argue that BALD lacks awareness of the input distribution, leading to the prioritization of irrelevant data, especially in real-world datasets with varying input relevance. The paper claims that BALD can be actively counterproductive in such cases, selecting obscure inputs that do not contribute to predictive performance.

Figure 1: The expected predictive information gain (EPIG) can differ dramatically from the expected information gain in the model parameters (BALD).

The paper uses the example of a supervised-learning problem where x,y∈R with a Gaussian process prior to demonstrate how a high BALD score need not coincide with any reduction in the predictive uncertainty of interest, EIGθ(x∗).

To overcome BALD's limitations, the authors derive EPIG from the Bayesian experimental design framework. Unlike BALD, which targets parameter uncertainty, EPIG directly targets predictive uncertainty on inputs of interest. This is achieved by introducing a target input distribution, p∗(x∗), and defining the goal as confident prediction of labels, y∗, associated with samples x∗∼p∗(x∗).

EPIG is defined as the expected reduction in predictive uncertainty at a randomly sampled target input, x∗, offering an alternative interpretation as the mutual information between (x∗,y∗) and y given x, denoted as I(x∗,y∗);y∣x. The paper also presents a frequentist perspective, stating that in classification settings, EPIG is equivalent (up to a constant) to the negative expected generalization error under a cross-entropy loss.

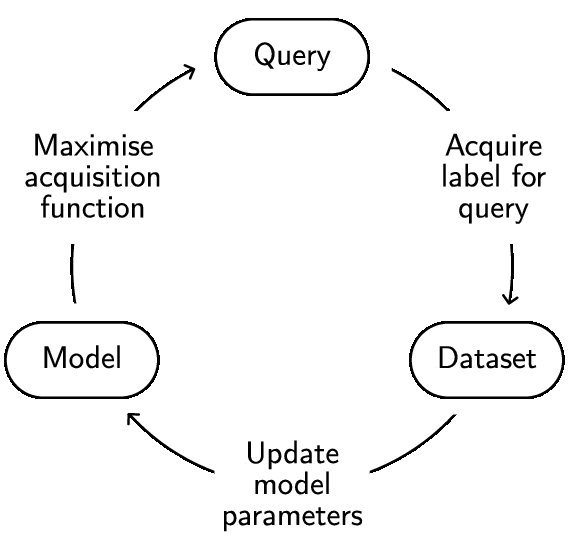

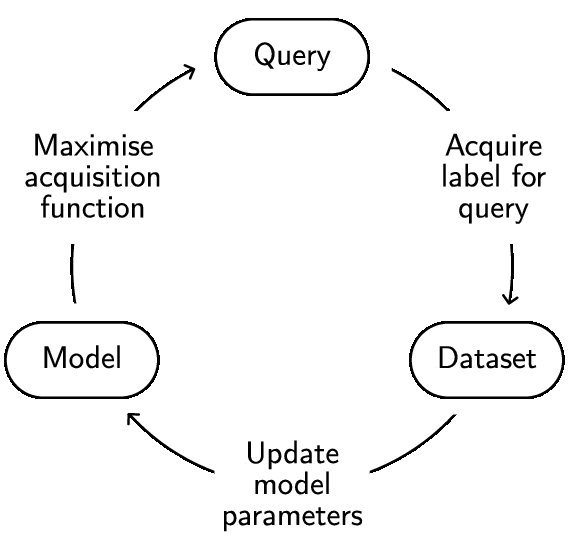

Figure 2: Active learning typically loops over selecting a query, acquiring a label and updating the model parameters.

Implementation Details

The practical implementation of EPIG involves estimating the expectation with respect to the target input distribution, p∗(x∗), using Monte Carlo methods. The paper discusses different scenarios for sampling x∗, including subsampling from a pool of unlabeled inputs, using samples from p∗(x∗) when available, and approximating p∗(x∗) using the model and the pool in classification problems.

The authors present two estimators for EPIG. The first, suited to classification, is

EPIG(x)≈M1j=1∑MKLp^ϕ(y,y∗∣x,x∗j)p^ϕ(y∣x)p^ϕ(y∗∣x∗j),

where x∗j∼p∗(x∗) and the p^ terms are Monte Carlo approximations of predictive distributions. The second estimator, for cases where integration over y and y∗ is not analytical, utilizes nested Monte Carlo estimation:

EPIG(x)≈M1j=1∑Mlog∑i=1Kpϕ(yj∣x,θi)∑i=1Kpϕ(y∗j∣x∗j,θi)K∑i=1Kpϕ(yj∣x,θi)pϕ(y∗j∣x∗j,θi),

where x∗j∼p∗(x∗), yj,y∗j∼pϕ(y,y∗∣x,x∗j) and θi∼pϕ(θ).

The paper acknowledges that the EPIG estimators have a computational cost of O(MK), comparable to BALD estimation for regression but potentially more expensive for classification due to the inability to collapse to a non-nested Monte Carlo estimation.

Experimental Results

The paper presents a comprehensive empirical evaluation of EPIG, comparing it against BALD across various datasets and models. The experiments include synthetic data, UCI datasets, and MNIST variations, demonstrating EPIG's superior or comparable performance in different scenarios.

The synthetic data experiments visually illustrate BALD's tendency to acquire labels at the extrema of the input space, while EPIG focuses on regions relevant to the predictive task. The UCI dataset experiments show EPIG outperforming BALD in several classification problems, validating its effectiveness in broader settings.

Figure 3: BALD can fail catastrophically on big pools.

The MNIST experiments include Curated MNIST, Unbalanced MNIST, and Redundant MNIST, designed to capture challenges in applying deep neural networks to high-dimensional inputs. EPIG consistently outperforms BALD, especially in Redundant MNIST, suggesting its usefulness in working with diverse pools.

Figure 4: In contrast with BALD, EPIG deals effectively with a big pool (105 unlabelled inputs).

Figure 5: EPIG outperforms or matches BALD across three standard classification problems from the UCI machine-learning repository (Magic, Satellite and Vowels) and two models (random forest and neural network).

Figure 6: EPIG outperforms BALD across three image-classification settings.

Figure 7: Even without knowledge of the target input distribution, p∗(x∗), EPIG retains its strong performance on Curated MNIST, Unbalanced MNIST and Redundant MNIST.

Furthermore, the paper investigates the sensitivity of EPIG to knowledge of the target data distribution, p∗(x∗). The results show that EPIG retains its strong performance even when this knowledge is limited or absent, demonstrating its robustness in practical scenarios.

Figure 8: EPIG outperforms two acquisition functions popularly used as baselines in the active-learning literature.

The paper discusses related work in Bayesian experimental design and active learning, highlighting the historical focus on maximizing information gain in model parameters. It acknowledges the contributions of \citet{mackay1992evidence,mackay1992information} in introducing the mean marginal information gain and discusses other prediction-oriented methods for active learning.

Conclusion

This paper makes a strong case for EPIG as a more effective acquisition function for Bayesian active learning compared to BALD, particularly in prediction-oriented settings. The authors demonstrate EPIG's ability to target information gain in predictions, leading to improved performance across various datasets and models. The paper concludes that EPIG can serve as a compelling drop-in replacement for BALD, with potential for significant performance gains when dealing with large, diverse pools of unlabeled data.