CholecTriplet2022: Show me a tool and tell me the triplet -- an endoscopic vision challenge for surgical action triplet detection

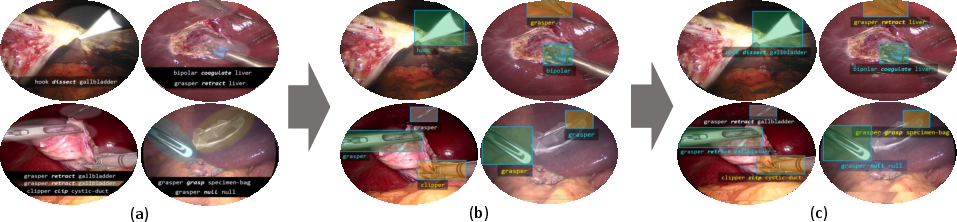

Abstract: Formalizing surgical activities as triplets of the used instruments, actions performed, and target anatomies is becoming a gold standard approach for surgical activity modeling. The benefit is that this formalization helps to obtain a more detailed understanding of tool-tissue interaction which can be used to develop better Artificial Intelligence assistance for image-guided surgery. Earlier efforts and the CholecTriplet challenge introduced in 2021 have put together techniques aimed at recognizing these triplets from surgical footage. Estimating also the spatial locations of the triplets would offer a more precise intraoperative context-aware decision support for computer-assisted intervention. This paper presents the CholecTriplet2022 challenge, which extends surgical action triplet modeling from recognition to detection. It includes weakly-supervised bounding box localization of every visible surgical instrument (or tool), as the key actors, and the modeling of each tool-activity in the form of <instrument, verb, target> triplet. The paper describes a baseline method and 10 new deep learning algorithms presented at the challenge to solve the task. It also provides thorough methodological comparisons of the methods, an in-depth analysis of the obtained results across multiple metrics, visual and procedural challenges; their significance, and useful insights for future research directions and applications in surgery.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper describes a worldwide research challenge called CholecTriplet2022. The goal was to teach computers to watch surgery videos and understand exactly what is happening, in detail. In particular, the challenge asked AI models to find and describe “action triplets” in the video: the instrument being used, the verb (the action), and the target (the body part or tissue). Think of it like “who did what to what,” but in surgery. For example: {grasper, retract, gallbladder}.

The challenge also stepped beyond just recognizing which triplets are present. It asked models to point to where, on the screen, the instrument’s tip is located at the same time—helping AI give precise, context-aware support during surgery.

What were the main questions?

The challenge focused on three simple but tough tasks that happen at the same time:

- Triplet recognition: Can the AI say which triplets are present in each video frame?

- Instrument localization: Can the AI draw a rectangle (a bounding box) around the tip of the instrument that’s acting?

- Box–triplet association: Can the AI match each instrument’s box to the right triplet?

Put together, this teaches AI both “what’s going on” and “where it’s happening.”

How did the researchers approach it?

The challenge used a big dataset called CholecT50. These are videos of a common keyhole surgery to remove the gallbladder (called laparoscopic cholecystectomy). The dataset includes 50 surgeries and many labels of triplets like instrument, verb, and target. Here’s how the setup worked:

- Training data: Teams got labels about which triplets were present (like checkboxes), but they did not get exact locations of instruments. This encourages “weak supervision,” which means learning from limited hints rather than perfect answers.

- Test data: The test set did include bounding boxes around instrument tips, so the organizers could fairly judge how well models learned to localize without being directly taught those box positions.

To measure performance, the challenge used standard computer vision metrics:

- Average Precision (AP): A score that balances correct detections with false alarms.

- Intersection over Union (IoU): Measures how much the predicted box overlaps the true box. IoU 0.5 means at least half overlap, which is quite strict, especially when training without box labels.

Teams used modern deep learning tools, like:

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): These are common for image tasks, like letting a computer learn patterns in pixel grids.

- Transformers: A type of neural network good at understanding sequences and attention (what to focus on in the video).

- Class Activation Maps (CAMs): A way for the model to highlight “hotspots” in the image (like the instrument tip) that influenced its decision.

- Knowledge distillation: Teaching a “student” model using the outputs of a stronger “teacher” model (often to make learning smoother or more reliable).

Because the training labels didn’t include instrument positions, many teams used clever tricks:

- Weak supervision: Learning to find instrument locations from only triplet presence labels and some extra hints.

- Pseudo-labels: Automatically generating “fake” training boxes using a detector trained elsewhere, then using those to improve the model.

- Graph modeling: Connecting what tends to happen together (like certain instruments usually performing certain actions on certain targets) to improve predictions.

The organizers also built a careful validation system so teams could test their code locally, then submit it using Docker containers. This made the judging fair, consistent, and reproducible.

What did they find?

The challenge reported results across three tasks. Because localization was learned with weak supervision (without direct box labels in training), the evaluation was intentionally strict:

- Triplet recognition AP: about 18.8% to 35.0%

- Instrument localization AP: about 0.3% to 41.9%

- Triplet detection AP (recognition + localization together): about 0.08% to 4.49%

Why such a wide range and low numbers in some parts? A few reasons:

- The test was strict (IoU 0.5) and the training didn’t include boxes, which makes learning “where” very hard.

- Surgery videos are complex: tools are shiny, tiny, move fast, and can be partially hidden by tissue or smoke. Lighting changes and camera motion add difficulty.

- Triplets are fine-grained: The model must get the instrument, action, and target right—and link them to the correct spot on screen.

Even so, the challenge showed that models can learn meaningful signals: better recognition of triplets and promising, if imperfect, localization. Several teams proposed new ideas that improved results compared to the baseline method.

Why does this matter?

If AI can understand surgery videos precisely and reliably in real-time, it can:

- Give surgeons smart guidance during operations, like reminders or warnings.

- Help standardize training and feedback for medical students and staff.

- Detect risky situations early (for example, if the wrong tissue is being cut).

- Support automatic report generation, saving time and improving records.

This challenge pushes the field from simple “phase recognition” (broad steps of surgery) to detailed “action triplets” that capture tool-tissue interactions at the moment they happen. That’s a big step toward useful AI assistants in the operating room.

Final thoughts

CholecTriplet2022 showed that it’s possible to train AI to both recognize what’s happening in surgery videos and find where it’s happening—mostly from weak labels. The results suggest we need better training signals, smarter modeling, and perhaps more annotated data to reach high accuracy. Still, the challenge created shared benchmarks, sparked new techniques, and provided insights into how AI can become a practical, trustworthy helper for surgeons. As future datasets add more precise labels and algorithms improve, these systems could make surgeries safer, faster, and more consistent.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.