One Thousand and One Hours: Self-driving Motion Prediction Dataset

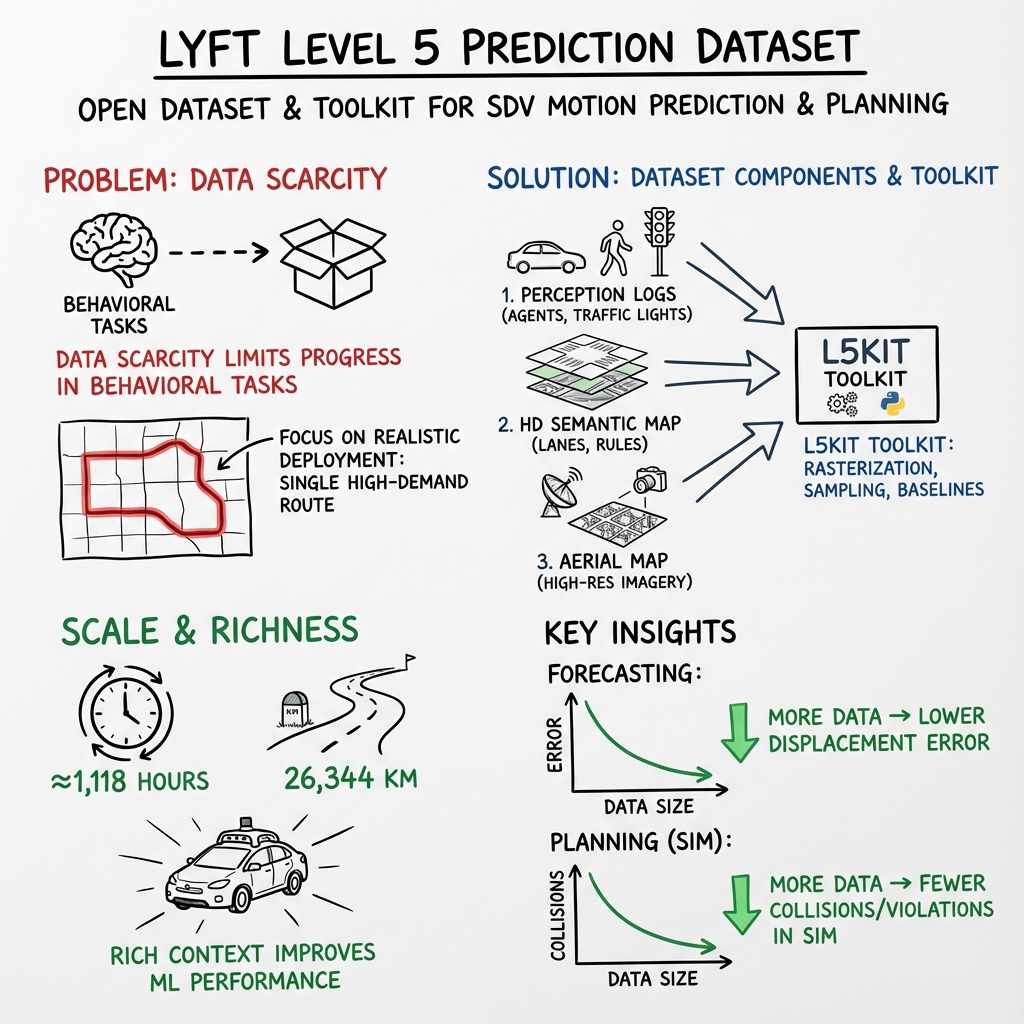

Abstract: Motivated by the impact of large-scale datasets on ML systems we present the largest self-driving dataset for motion prediction to date, containing over 1,000 hours of data. This was collected by a fleet of 20 autonomous vehicles along a fixed route in Palo Alto, California, over a four-month period. It consists of 170,000 scenes, where each scene is 25 seconds long and captures the perception output of the self-driving system, which encodes the precise positions and motions of nearby vehicles, cyclists, and pedestrians over time. On top of this, the dataset contains a high-definition semantic map with 15,242 labelled elements and a high-definition aerial view over the area. We show that using a dataset of this size dramatically improves performance for key self-driving problems. Combined with the provided software kit, this collection forms the largest and most detailed dataset to date for the development of self-driving machine learning tasks, such as motion forecasting, motion planning and simulation. The full dataset is available at http://level5.lyft.com/.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

This paper introduces a very large, carefully prepared dataset to help self-driving cars learn how people and vehicles move. Think of it like a huge “traffic diary” recorded from self-driving cars that shows where nearby cars, bikes, and people were, how they moved, and what the roads and signs looked like. The goal is to make it easier and faster for researchers to build safer, smarter driving systems.

The main goals and questions

The authors set out to:

- Build and share the largest, most detailed public dataset for predicting how traffic will move (called motion prediction) and for planning a self-driving car’s path.

- Test a simple idea: do bigger, richer datasets help machine learning models drive better? (Spoiler: yes.)

- Provide tools so researchers and students can use the data easily, not just big companies with private data.

How they built it (in simple terms)

The team recorded real-world driving along a single, busy route in Palo Alto, California, over about four months. Instead of covering an entire city, they focused on one 6.8-mile route—similar to how a bus might serve a popular line—because early self-driving services may start on limited, high-demand routes.

Here’s what’s inside and how to imagine it:

- A huge set of driving “clips”: 170,000 short scenes, each 25 seconds long (over 1,000 hours total), captured by 20 self-driving cars. Each scene is like a mini movie where every frame shows the positions and motion of nearby cars, cyclists, and pedestrians.

- A “semantic map”: This is a map that knows the rules of the road—where lanes are, which way you can go, speed limits, crosswalks, and where traffic lights and signs are. Imagine a regular map plus the road rules drawn right on top.

- An aerial image: A very detailed top-down photo of the area (like what you see in satellite view), which helps models understand the layout of roads and surroundings.

- A software toolkit (L5Kit): Code to load the data, visualize scenes from a bird’s-eye view (a top-down map view, like looking at a board game), and train basic models.

What did they actually model?

- Motion prediction: Teach a model to guess where another car (or person on a bike or walking) will be in the next few seconds. They trained a standard image-based neural network (ResNet-50) using top-down “map pictures” that include lanes, road shapes, and the recent motion history of each moving object. You can think of it like the model looking at a moving “dot” on a map with lanes drawn in, then predicting where that dot will go next.

- Motion planning (for the self-driving car itself): Train a model to choose a safe path for the self-driving car. They used “imitation learning,” which is like learning by example—copying good driving from the recorded data—and added small “what-if” nudges (perturbations) so the model also learns how to recover from mistakes.

A few technical terms explained simply:

- Bird’s-eye view (BEV): A top-down picture of the road, like looking from above.

- Semantic map: A map that includes meanings and rules (lanes, directions, speed limits).

- Imitation learning: Training by watching and mimicking the “right” behavior from examples.

What they found and why it matters

The authors ran baseline tests to see how well models perform when trained on different amounts of data. The key takeaways:

- More data = better predictions. Models that saw more of the 1,000+ hours made more accurate guesses about where cars and people would be in the next few seconds.

- Recent history helps. When models were given a short history of how something was moving, they predicted the future more accurately than when they only saw the current moment.

- Planning improved with more data too. The model that chooses the self-driving car’s path made fewer mistakes (like going off the road or breaking rules) as it was trained on larger portions of the dataset.

Why this is important:

- Accurate motion prediction helps the car plan safe, smooth paths and avoid collisions.

- Better planning means safer, more reliable autonomous driving—especially in complex traffic.

- Sharing a large, high-quality, open dataset (with tools) lets more people contribute to progress, not just companies with private data.

What this could lead to

This dataset makes it easier for students, researchers, and engineers to build and test smarter self-driving systems. It supports two crucial steps: predicting how others will move and planning what the self-driving car should do next. The results also suggest that even more data can keep improving safety and performance. In the near term, this approach could help launch self-driving services on specific popular routes first—where performance and risks are easier to manage—before expanding more widely.

In short, this work provides the community with a giant, well-organized “learning playground” for self-driving cars, showing that scale and detail really do make a difference.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of concrete limitations and unresolved questions left by the paper that future researchers could address:

- Geographic and route diversity: The dataset covers a single 6.8-mile suburban route in Palo Alto; generalization to different cities, road types (urban cores, rural, highways), and infrastructure remains untested.

- Temporal and environmental coverage: Logs are restricted to daytime (8 AM–4 PM) across October–March; the impact of nighttime, low-light, seasonal changes, varied traffic densities, and adverse weather (rain, fog) is unknown and not labeled.

- Perception-derived labels without ground-truth audit: All actor states come from an in-house perception stack rather than human-verified ground truth; there are no reported error rates, confidence calibration, or label noise characterization (e.g., false positives/negatives, occlusion-induced drift).

- Class imbalance and actor taxonomy: 92.47% of detections are cars; pedestrians/cyclists are underrepresented and heavy vehicles (buses, trucks), micro-mobility, and emergency vehicles appear absent—how this skews forecasting/planning performance is unaddressed.

- Scenario coverage and rarity: The dataset likely contains few rare or safety-critical events (near-misses, collisions, emergency maneuvers); there’s no scenario taxonomy or tags to retrieve edge cases for robust training and evaluation.

- Split strategy and data leakage risk: While vehicles are split across train/val/test, the same physical route and map appear in all sets; spatiotemporal correlations and near-duplicate scenes could inflate performance—no time-based, route-held-out, or season-held-out splits are evaluated.

- Map change dynamics: HD map elements (lane geometry, restrictions, signs) are treated as static, with no tracking of temporal changes (construction, lane closures, temporary signage); how map drift or updates affect models is unexplored.

- Use of dynamic signals: Traffic light states are included, but the baselines do not quantify their contribution or evaluate model performance with versus without dynamic signals (e.g., light state, turn signals) or right-of-way rules.

- Aerial versus semantic map ablations: The paper asserts aerial imagery could enable “map-free” solutions but provides no quantitative ablations comparing semantic-only, aerial-only, and combined inputs, nor guidance on the minimal map needed.

- Forecasting model simplicity: Baselines predict a single unimodal trajectory with L2 loss; multi-modal forecasting, uncertainty quantification, and evaluation using standard metrics (minADE/minFDE over K modes, calibrated probabilities) are not attempted.

- Interaction modeling: Forecasting baselines do not explicitly model agent–agent interactions or social compliance (yielding, merging, gap acceptance); no comparison to vectorized or graph-based state-of-the-art approaches (e.g., VectorNet) is provided.

- Horizon limitations: Only 5-second horizons are evaluated; performance and failure modes at longer horizons (8–10+ seconds) and with varying history lengths beyond 1 second are left unexplored.

- Closed-loop planning evaluation realism: Planning is evaluated in a non-reactive log-replay where other agents are scripted to follow recorded trajectories; this prevents realistic interaction testing (e.g., how others react to SDV maneuvers) and may mask critical failure modes.

- Planning metrics and benchmarks: Planning results are shown qualitatively and via plots without standardized, reproducible benchmark metrics (e.g., collision rate, off-road rate, traffic-rule violation definitions, comfort/jerk limits), baselines (e.g., hand-crafted planners), or statistical significance.

- Perception–planning coupling: The planning evaluation excludes errors arising from perception degradation when the SDV diverges from logged positions; how to robustly couple perception, forecasting, and planning in closed loop remains open.

- Scaling laws and data efficiency: While performance improves with more data, there is no analysis of returns-to-scale, diminishing gains, sample complexity, or the role of data diversity versus quantity; guidance for optimal dataset growth is missing.

- Dataset metadata and annotations: There is no per-scene metadata for weather, lighting, traffic density, construction, or special events; lack of tags hinders targeted sampling, domain shifts studies, and curriculum learning.

- Actor identity and tracking fidelity: The paper does not quantify ID-switch rates or trajectory continuity quality from the perception system; forecasting models may be affected by tracking noise, which is not measured.

- Map accuracy and provenance: HD map creation via SLAM and human annotation is described, but map accuracy, lane boundary precision, and annotation inter-rater reliability are not reported or benchmarked.

- Route intent and SDV signals: The dataset does not describe availability of SDV intent signals (planned route, turn signals, navigation goals), which are crucial for both forecasting (others reacting to SDV) and planning tasks.

- Ethical and privacy considerations: There is no discussion of privacy practices (e.g., pedestrian anonymization) or bias analysis (demographics, neighborhood-specific behaviors), which could affect downstream model fairness.

- Tooling and reproducibility details: Baseline training lacks full hyperparameter disclosure, seed variability studies, and computational resource requirements; reproducibility and variance across runs are not quantified.

- Transfer learning and domain adaptation: How models trained on this single-route dataset adapt to new routes/maps (zero-shot or few-shot) is not studied; benchmarks for cross-route/domain adaptation are absent.

- Simulation fidelity for planning: There is no reactive, agent-based simulation or learned world model to enable realistic closed-loop testing; integrating behaviorally realistic agents and evaluating robustness under interaction is an open need.

Practical Applications

Overview

Below are actionable, real-world applications that flow from the paper’s dataset, tools (L5Kit), and baseline results on motion forecasting and planning. Each application notes sector relevance, plausible tools/products/workflows, and assumptions or dependencies affecting feasibility. Applications are grouped into Immediate and Long-Term categories.

Immediate Applications

These can be deployed now using the released dataset, HD semantic map, aerial imagery, and L5Kit.

- Industry (Autonomous Mobility): Route-constrained motion forecasting benchmarking and model training

- Tools/products/workflows: Use L5Kit to sample agent- or SDV-centered BEV rasters; train PyTorch ResNet-50 forecasting models; evaluate displacement error across horizons; perform ablations on history length and training set size.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain is Palo Alto, daytime, dry weather; perception output (not raw sensors); compute resources and PyTorch familiarity; licensing compliance.

- Industry (ADAS suppliers): Improve path prediction modules with HD map priors

- Tools/products/workflows: Integrate lane connectivity, turn restrictions, traffic light states into trajectory prediction; refine planner cost functions using lane-level annotations and historical agent motions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Mapping priors and behavior priors align with target deployment geography; careful domain adaptation to other cities and sensor suites.

- Software/Robotics (Simulation vendors and AV stack developers): Scenario library and log-replay integration for planner testing

- Tools/products/workflows: Import zarr-encoded scenes into existing simulators; log-replay with SDV closed-loop control; measure collisions/off-road/traffic violations; seed synthetic perturbations for imitation learning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Non-reactive participants (log-replay) can limit realism; need interfaces to ROS/simulation engines; safety metrics defined consistently.

- Mapping/GIS (Digital map providers): Lane-level HD map QA and enrichment using aerial imagery

- Tools/products/workflows: Automated map validation against 6 cm/pixel aerial tiles; detect missing lane segments, crosswalks, speed bumps; semi-automated curation workflows with human-in-the-loop.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality of aerial imagery, alignment accuracy (SLAM-derived localization), map change management over time.

- Academia (Computer Vision/Robotics): Reproducible benchmarks for motion forecasting and learned planning

- Tools/products/workflows: Course assignments and papers replicating baselines; systematic data-scaling studies; model comparison on ADE and horizon-specific errors; open-source sharing via L5Kit.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of GPUs; adherence to dataset splits; ethical and licensing use in classrooms.

- Policy (Transport safety research): Pilot benchmarking framework for pre-certification analyses

- Tools/products/workflows: Use dataset to define minimum performance thresholds for prediction/planning tasks; study data-scaling effects on safety-critical metrics; convene regulators/industry around shared benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Limited to one suburban corridor; not a substitute for on-road validation; requires stakeholder buy-in.

- Insurance/Finance (Risk analytics): Route-specific collision/violation risk profiling for constrained AV operations

- Tools/products/workflows: Analyze incident proxies (collisions/violations in sim) vs. training data volume; build actuarial models for fixed-route AV pilots; sensitivity analysis for model drift and data freshness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Simulation limitations; transferability from Palo Alto route to insured routes; regulatory acceptance of model-based evidence.

- Education (Workforce development): Bootcamps and hackathons on BEV rasterization and forecasting

- Tools/products/workflows: Hands-on labs using L5Kit; coding challenges on multimodal prediction; leaderboard-based competitions (ADE, horizon errors).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Compute access for participants; curated subsets for quick iteration.

- Software (MLOps/Data engineering): High-throughput training pipelines for large zarr datasets

- Tools/products/workflows: Multi-threaded sampling; cloud-based distributed training; reproducible data splits; experiment tracking on data subset sizes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Storage/IO optimization; cluster setup; robust versioning of datasets and maps.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, reactive simulation, regulatory coordination, or broader data coverage.

- Industry (Autonomous Mobility): Route-first autonomous shuttle deployment strategy for ride-hailing

- Tools/products/workflows: Safety case built on fixed high-demand corridors; planner trained with perturbations and closed-loop metrics; staged expansion across similar corridors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory approval; reactive simulation and on-road trials; generalization beyond daytime and weather constraints; robust perception integration in deployment.

- Software/Robotics: Learned planners that outperform hand-crafted optimization in closed-loop driving

- Tools/products/workflows: Imitation learning with synthetic perturbations; integration of interactive simulation with reactive agents; hybrid ML+optimization planners.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Distribution shift mitigation; large-scale interactive sim; safety validation process; rare-event modeling.

- Mapping/GIS: Map-free or map-light motion forecasting leveraging aerial imagery

- Tools/products/workflows: Models trained directly on aerial tiles to infer drivable space and behavior priors; lightweight deployments in regions with sparse HD maps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robustness to imagery updates, occlusions, seasonal changes; generalization to varied urban morphologies.

- Urban Planning/Transportation: Data-driven intersection redesign and signal timing optimization

- Tools/products/workflows: Use forecasted behaviors to simulate queue lengths, conflicts; propose re-striping, protected turns, crosswalk relocation; integrate with DOT signal control systems.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Need multi-route/multi-time datasets; local data collection for target city; integration with traffic engineering tools and V2I infrastructure.

- Policy/Standards: Evidence-based safety validation and pre-certification protocols

- Tools/products/workflows: Standardized datasets and metrics for forecasting/planning; scenario banks including rare events; third-party audit frameworks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Broader geographic/time/weather coverage; consensus on metrics; governance for dataset maintenance and fairness.

- Energy/Environment: Eco-driving trajectory planning to reduce idling and emissions on fixed routes

- Tools/products/workflows: Planners optimizing speed profiles with map-informed constraints; coordination with signal timing; fleet-level energy analytics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: V2I/V2X capabilities; real-time signal data; multi-modal traffic acceptance; measurable emissions baselines.

- Public Safety/Healthcare: Improved emergency corridor management using predictive pedestrian/vehicle flow

- Tools/products/workflows: Predictive routing for ambulances along designated corridors; dynamic signal preemption; pedestrian conflict forecasting near hospitals/schools.

- Assumptions/dependencies: City adoption of corridor strategies; integration with CAD/dispatch systems; expanded datasets covering relevant zones and times.

- Insurance/Finance: Capital allocation and risk pricing for corridor-by-corridor AV rollout

- Tools/products/workflows: Performance-scaling analysis informs investment thresholds; scenario-based stress testing; portfolio diversification across routes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable cross-city transfer learning; recognition of model-based metrics by regulators and reinsurers; ongoing data refreshes.

- Education/Workforce: Scalable training pipelines for AV engineering and operations

- Tools/products/workflows: Curricula on data-centric AV development; capstone projects on planning and forecasting; internship-to-ops pathways for corridor deployments.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Industry-academia partnerships; broader datasets to avoid overfitting to a single locale.

- Software/MLOps: Petascale data management for tens of thousands of hours of motion data

- Tools/products/workflows: Data versioning, lineage tracking, and bias audits; federated training across fleets; synthetic data generation aligned with real distributions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cloud costs and governance; privacy-preserving pipelines; standard APIs for cross-organization collaboration.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies to note

- Geographic and temporal scope: Single suburban Palo Alto route; daytime (8 AM–4 PM); limited weather variability; generalization needed for other contexts.

- Simulation realism: Non-reactive log-replay limits closed-loop fidelity; reactive multi-agent simulation is necessary for production-grade validation.

- Data modality: Dataset exposes perception outputs (poses, boxes, labels)—not raw sensors; domain shift may arise with different sensors or perception stacks.

- Map currency and alignment: HD semantic map accuracy depends on SLAM and human annotations; aerial imagery must be up-to-date and well-aligned.

- Compute and expertise: Effective use requires GPUs, data engineering for zarr arrays, and ML expertise; organizations must plan for MLOps.

- Licensing and ethics: Respect dataset terms; ensure privacy and fairness; avoid overfitting to the single corridor and translating biases elsewhere.

- Regulatory acceptance: Benchmarks and safety metrics must be agreed upon; on-road validations are essential for deployment beyond research.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.