Stakeholder-Based Ethics Analysis

- Stakeholder-Based Ethics Analysis is a structured framework that integrates diverse ethical norms using formal argumentation and normative systems.

- It employs models like the Jiminy Advisor to create, compare, and revise ethical arguments, ensuring transparent and auditable decision-making.

- The approach supports real-time ethical negotiation in multi-agent systems while addressing challenges like scalability and context-sensitive conflict resolution.

Stakeholder-Based Ethics Analysis is a structured approach to identifying, integrating, and negotiating the values, interests, and potential impacts of all parties affected by technological systems, especially within the context of autonomous, AI-driven, or socio-technical environments. It is grounded in formal theories from normative systems, value-sensitive design, and argumentation frameworks, and is motivated by the need to reconcile often competing moral claims among heterogeneous stakeholders—ranging from system developers and manufacturers to end-users, regulatory bodies, and the broader public. By systematically analyzing and incorporating these perspectives, stakeholder-based ethics analysis seeks to provide principled, transparent, and explainable guidance for ethical system behavior and decision-making.

1. Theoretical Foundations and Normative Systems

Stakeholder-based ethics analysis is rooted in foundational work in normative systems and deontic reasoning. Early contributions by Alchourrón and Bulygin and input–output logics by Makinson establish rigorous methods for representing and reasoning about “if–then” norms and their conflicts. These systems utilize formal structures to capture stakeholder-specific norms as sets of defeasible rules, which are not globally absolute and may admit exceptions. Within the stakeholder-based paradigm, each party’s moral perspective is modeled as a normative system, encoding obligations, permissions, and prohibitions relevant to their viewpoint.

A key architectural principle is that the integration of these multiple stakeholder systems does not presuppose a unifying moral theory but instead maintains their diversity while providing procedural mechanisms to resolve conflicts when they arise. This is achieved through formal argumentation theory, enabling technical representation and resolution of complex normative interdependencies.

2. Formal Argumentation Frameworks

Structured argumentation frameworks undergird stakeholder-based ethics analysis, supplying the tools for comparing, combining, and adjudicating between competing norms from multiple sources. Drawing on seminal work by Dung and subsequent developments, these frameworks represent stakeholder norms as arguments, with relationships (such as attacks or defeats) reflecting incompatibilities or priorities among them.

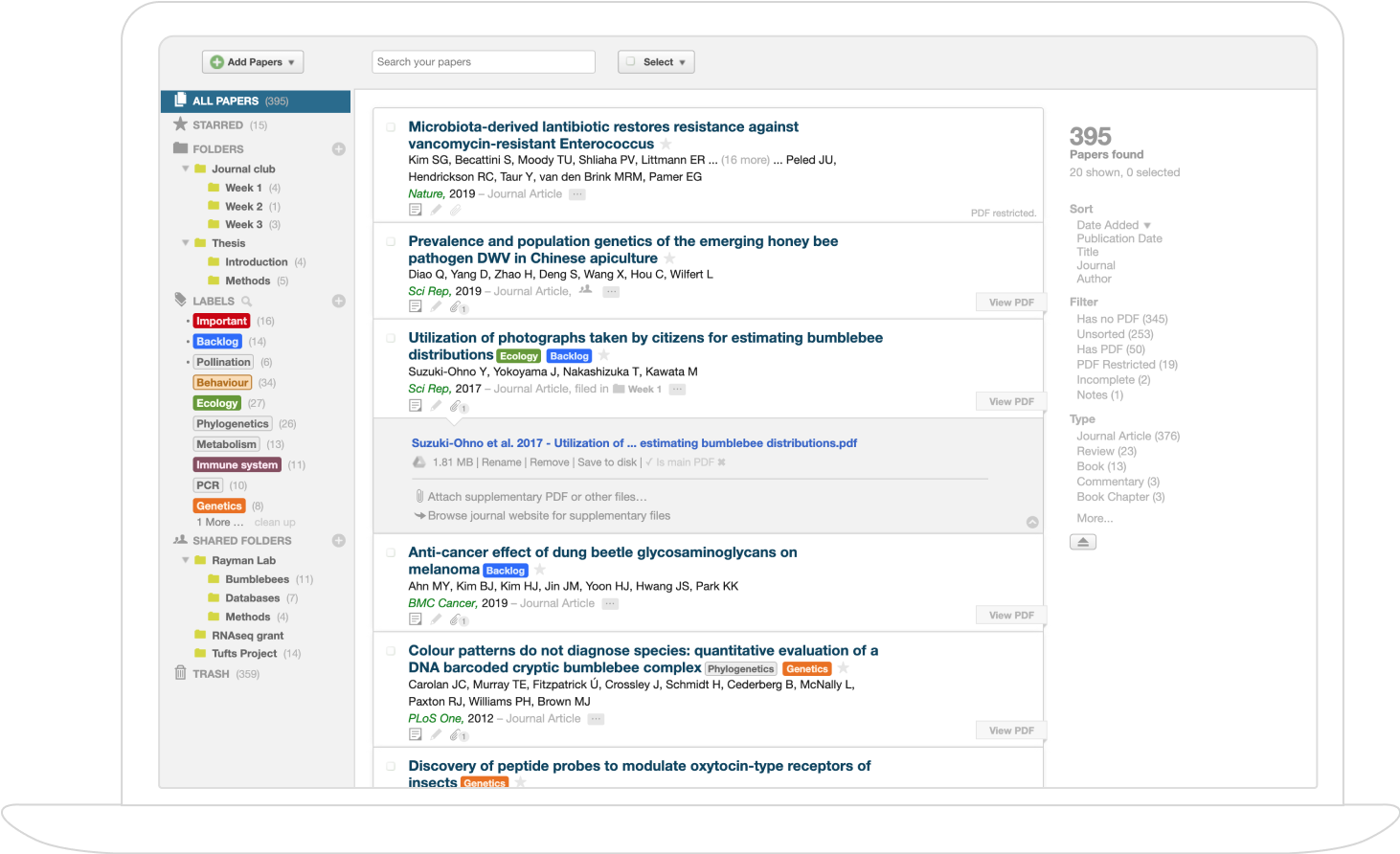

In the "Jiminy Advisor" model, three principal forms of ethical dilemma resolution are instantiated:

- Argument Aggregation: New arguments reflecting novel stakeholder positions are added to the argument pool; sometimes, this suffices to resolve a dilemma if arguments are not in conflict.

- Attack Relationship Construction: Attacks (defeats) between arguments—often corresponding to explicit conflicts—are introduced to make inter-norm relationships apparent and actionable.

- Attack Revision (Priority Ordering): If conflicts persist, higher-level context-sensitive rules or priorities may be invoked to revise the attack structure, effectively deciding which stakeholder's norm should override another's in specific settings.

At a technical level, these strategies correspond to operations on the argumentation graph—namely, adding nodes (arguments), edges (attacks), or modifying existing edges in accordance with stakeholders' relative authority or contextual relevance. The extension semantics of the underlying formal argumentation framework (such as preferred, grounded, or stable extensions) are then used to determine which positions are ultimately accepted, and to supply principled explanations for the system’s ethical recommendations.

3. Procedural Resolution and Explanation

Stakeholder-based ethics analysis provides not only conflict resolution but also a rigorous basis for transparent explanations. Explanatory mechanisms draw directly from the formal structure of the argumentation and normative system: each recommended action or resolution can be traced back to a chain of argumentation extensions and priority rules, supplying an explicit rationale for why certain stakeholder views prevail in a given context.

Three levels of procedural analysis are distinguished:

- Direct Resolution: If arguments from different stakeholders are compatible, resolution is direct and explanation follows from the accepted extension.

- Combined Expertise: Where combining the normative systems allows a broader set of arguments, resolution may depend on the aggregate knowledge.

- Context-Sensitive Tie-Breaking: Where neither argument nor combined knowledge fully resolves the situation, the system applies explicit, context-dependent rules (such as deference to legal requirements, manufacturer obligations, or user safety).

The formal argumentation graph explains both how conflicts arose and the specific operations leading to resolution, directly supporting post hoc justification and auditability. Such traceability is critical for facilitating system transparency in complex ethical environments including, but not limited to, autonomous vehicles, healthcare robotics, or AI-driven decision support systems.

4. Applications and Implementation Architectures

Stakeholder-based ethics analysis, as formalized in the Jiminy architecture, is implemented in autonomous and multi-agent systems requiring real-time moral negotiation. In such systems, each stakeholder’s normative system is encoded as a set of rules or logical statements, and the argumentation framework is instantiated as a formal graph structure amenable to automated reasoning.

Key implementation elements include:

- Normative Systems Layer: Encodes each stakeholder’s ethical positions using formal logics (e.g., deontic or input–output frameworks).

- Argumentation Layer: Constructs and updates argument and attack relationships as stakeholders' perspectives and environmental context evolve.

- Conflict Detection and Resolution Module: Applies the three-pronged resolution pathways (add arguments, add attacks, revise attacks/priorities) to reach agreements dynamically.

- Explanation Engine: Extracts human-interpretable explanations from the argumentation structure for all recommendations or actions taken.

The modularity of the approach allows integration with systems in regulatory-sensitive domains, supports collaborative decision-making, and satisfies the increasing demand for explainable and auditable AI. The architecture is not bound to specific application domains and has been referenced in literature concerning multi-agent system governance, collaborative autonomous robotics, and machine ethics explainability.

5. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths:

- Logical Rigor and Flexibility: The framework’s grounding in formal deontic and argumentation logic allows precise modeling of stakeholder norms and systematic conflict resolution without collapsing distinct value systems into a monolithic viewpoint.

- Procedural Transparency: By tracing every resolution (or persistent disagreement) to a formal argumentation structure, the model supports auditing and explanation at a granular level.

- Extensibility: The architecture accommodates additional stakeholders or changing priorities without reengineering the foundational logic.

Limitations:

- Scalability: As the number and complexity of stakeholders and their corresponding arguments grow, the computational cost of generating and evaluating argumentation frameworks increases.

- Context Sensitivity: Genuine contextual reasoning—especially in dynamically evolving environments—may require integration with real-time data and ontologies, which pose challenges in mapping abstract arguments to concrete operational data.

- Meta-Ethical Challenges: The approach presupposes that stakeholder values can be formally encoded and that their conflicts are resolvable within a given logic; situations involving radically incompatible or incommensurable values may resist formal compromise.

6. Implications for Research and Practice

The stakeholder-based approach, notably as articulated in "The Jiminy Advisor" (Liao et al., 2018), has established a strong theoretical and technical foundation for embedding pluralistic ethical reasoning in autonomous and intelligent systems. It advances the field beyond single-moral-theory or mono-stakeholder models by enabling persistent, explainable, and formally auditable negotiation among diverse perspectives.

This framework supports not only ethically aware behavior but also compliance with emerging governance and audit requirements, especially in regulated environments. Its adoption in practical systems is anticipated to support trustworthy AI deployment, transparent decision support, and collaborative human–machine interaction in socio-technical contexts. Ongoing research is focused on scalability, richer context integration, and empirical validation across sectors such as healthcare, public services, and autonomous vehicles.