Online Political Participation Technologies

- Online political participation technologies are digital tools and platforms that facilitate citizen engagement via e-participation systems, online assemblies, and campaign management.

- They integrate AI and computational methods, using techniques like NLP and network analysis to enhance deliberation and dynamically aggregate political preferences.

- Legal compliance, security concerns, and algorithmic biases present challenges that demand multidisciplinary approaches to ensure inclusive and effective political participation.

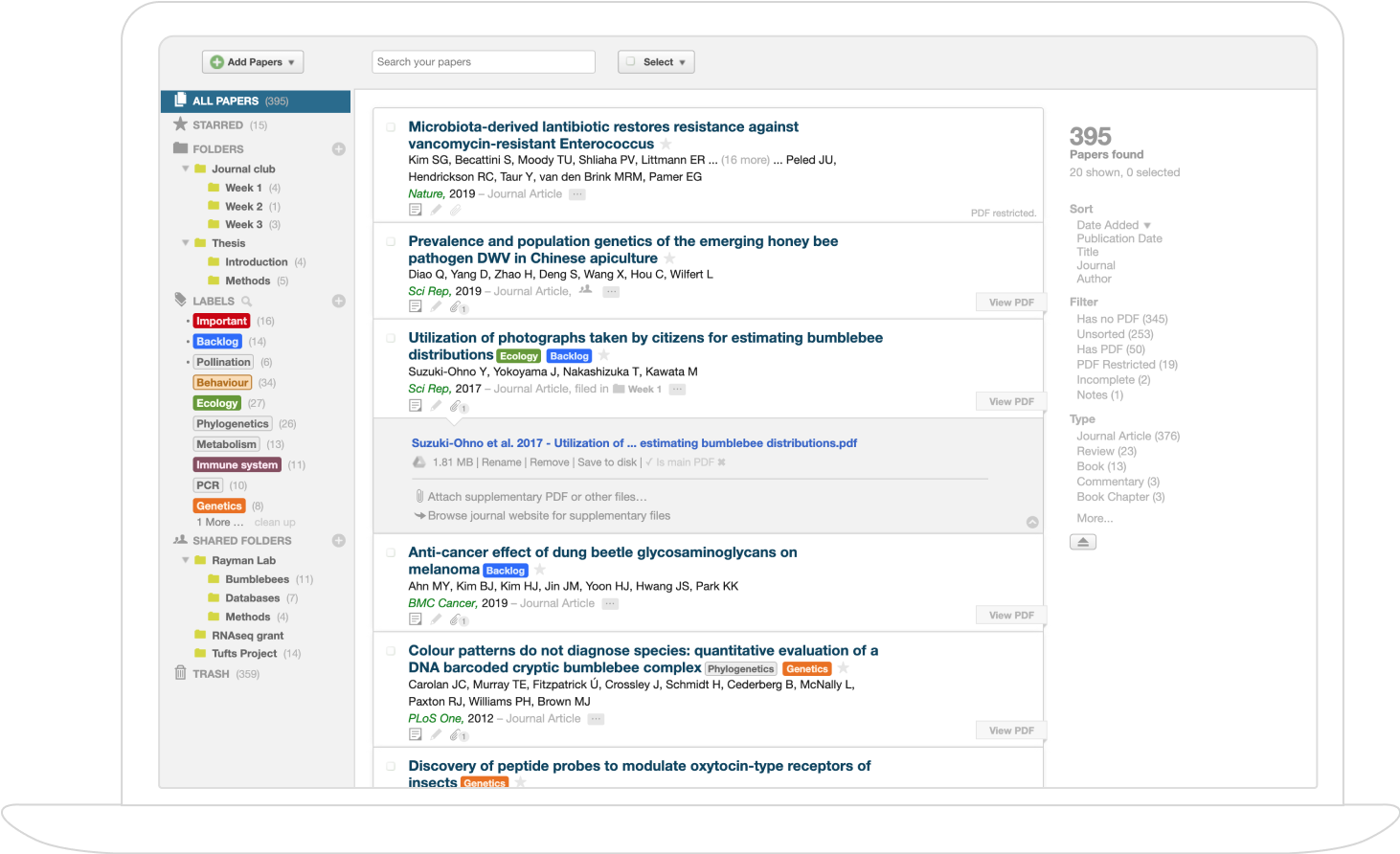

Online political participation technologies encompass the digital tools, platforms, and algorithmic infrastructures that enable, mediate, and analyze the collective engagement of citizens, politicians, and organizations in political processes via the Internet. These technologies include campaign and reputation management platforms, e-participation systems, deliberative platforms, AI-assisted participatory infrastructures, computational politics tools, and online assemblies. Their function spans information dissemination, deliberation, preference aggregation, electoral mobilization, civic co-production, and the monitoring and moderation of digital discourse.

1. Foundations and Key Modalities

Online political participation technologies originated with the proliferation of Web 2.0 tools, which facilitated two-way interactions between political actors and the public beyond static information provision. Early adoption occurred in both resource-constrained local campaigns and more technologically robust national efforts. Modalities include static sites, blogs, custom social networks, online petitioning, e-government platforms, participatory budgeting tools, social media channels, and real-time deliberation systems. Each modality offers distinct technical affordances, engagement practices, and regulatory implications (Seigneur, 2010, Bojic et al., 2016, Sousa et al., 20 Sep 2025).

A typical architecture table illustrating this diversity is as follows:

| Modality | Primary Function | Example Cases/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Static/Dynamic Web | Reputation management, info push | Candidate websites/blogs |

| Custom Platforms | Deliberation, proposal voting | Better Reykjavik, Decidim |

| Social Networks | Broadcast, mobilization | Facebook, YouTube |

| E-Gov Platforms | Policy feedback, consultation | Saudi e-government portal |

| Participatory Budgeting | Proposal, allocation, monitoring | Participe Mais (Sao Paulo) |

2. Engagement Architecture, Deliberation, and Participation Dynamics

Design features directly shape the nature and consequences of online political engagement (Frappier, 2023, Aragón et al., 2017). Key patterns include:

- Threaded and forum-oriented discussion structures enable modular, asynchronous debate, but often fragment deliberation if not balanced by argument aggregation or effective interface cues (Frappier, 2023).

- Voting and ranking mechanisms (e.g., pros/cons columns, star ratings, approval/ranking hybrids) aggregate collective preferences and confer legitimacy, but can either foster consensus or amplify polarizing dynamics (Navarrete et al., 2022).

- Hybrid designs—explicit comment alignment, as in Decidim Barcelona, or participatory budgeting with stages for proposal, voting, and monitoring—address deliberative deficits by visually distinguishing dissent and enabling extended cascades of substantive argument (Aragón et al., 2017, Bojic et al., 2016).

- Social information visibility (e.g., trending petitions, trending proposal lists) heavily influences attention allocation and the distribution of participation, amplifying “rich-get-richer” effects and social influence (Hale et al., 2014).

Significant behavioral phenomena have been documented, such as differentiated engagement for static vs. dynamic platforms, with dynamic, frequently updated, media-rich content generating substantially higher participation and visibility (Seigneur, 2010). However, across country contexts, “official” party presence often gives way to uncontrolled, anarchic, supporter-driven spaces with limited top-down control (Emruli et al., 2011).

3. Sociotechnical, Legal, and Security Considerations

Platform deployment is shaped by legal, regulatory, and security factors:

- Legal compliance is essential for any political platform collecting personal data (e.g., France’s CNIL registration), communicating during black-out periods (e.g., restriction on election day updates), and managing user-generated content to avoid defamation and liability (Seigneur, 2010).

- Security provisions—such as CAPTCHA, cookie-based vote protection, or robust moderation—must strike a balance with usability and accessibility needs, particularly for older participants (Seigneur, 2010).

- Non-representative feedback and manipulation: Weak authentication (e.g., cookie-only voting) enables repeated manipulation, rendering community ratings statistically meaningless. Social network-based petitioning is vulnerable to influencer-driven non-participation or bribery, posing both constructive and destructive election control problems with proven computational intractability even on trees and for two candidates (De et al., 2024).

The sociomaterial perspective emphasizes that participation is a product of entangled human and technological agency, with platform algorithms, interface design, notification systems, and automated content curation all mediating community boundaries, accountability, and the contours of political identity (Harris et al., 2016).

4. AI, Machine Learning, and Computational Politics

Recent advancements have seen the integration of AI and machine learning at multiple layers in the participation pipeline:

- NLP: Used for automatic translation, sentiment and stance detection, argument mining (extracting claims/premises/conclusions), duplicate recognition, dialog summarization, and automated moderation—for example, via transformer-based models such as BERT and GPT-3 (Behrendt et al., 3 Jun 2025).

- Fact-checking and quality evaluation: Fact-checking pipelines detect, evidence, and rate claims; quality models predict deliberative features such as Discourse Quality Index (DQI) (Behrendt et al., 3 Jun 2025).

- AI-powered deliberation: AI is leveraged to cluster, systematize, and summarize citizen proposals; recommend relevant content; facilitate dialogue (detect consensus and polarizing clusters); enhance inclusion (chatbots, translation); and visualize or simulate budget/resource allocation scenarios with digital twins (Sousa et al., 20 Sep 2025).

- Computational politics: Methods span supervised classification (e.g., SVM, Naive Bayes, TF–IDF for user ideology detection), unsupervised clustering, latent topic modeling (LDA), network analysis (modularity, core decomposition, path length, etc.), and hybrid graph-textual modeling for misinformation and echo chamber detection (Haq et al., 2019, Garcia et al., 2015).

A representative attention mechanism for transformer-based architectures is:

This function underlies state-of-the-art moderation, summarization, and argument extraction systems used in deliberative platforms (Behrendt et al., 3 Jun 2025).

5. Effects on Participation, Deliberation Quality, and Political Competition

Quantitative evaluations reveal nuanced platform effects:

- Aggregate engagement: Interface features like trending lists or dynamic blogs drive higher engagement locally (e.g., 25,000+ views for a dynamic blog vs. 6,000 for a static rival) (Seigneur, 2010), but interface-driven social information may not increase overall participation—attention is instead redistributed towards popular options, amplifying the Gini coefficient (e.g., from 0.82 to 0.85, ) (Hale et al., 2014).

- Collective intelligence and knowledge co-production: Successful deliberative platforms require open-ended dialogue, sustained feedback loops, and mechanisms that transform individual inputs into emergent solutions. Systems failing to facilitate true deliberation (e.g., Decide Madrid, Better Reykjavik) suffer low proposal success and underrepresentation of marginalized groups (Davies et al., 2020).

- Polarization and network structures: Multiplex network analysis of platforms like politnetz.ch detects strong intra-party modularity ( up to $0.74$ in support networks), while comments—serving as debate—cross boundaries, supporting both polarization and cross-party connectivity. These metrics inform both the design of endorsement features and the timing of interventions against polarization (notably during pre-electoral periods) (Garcia et al., 2015).

- Social media adoption and campaign finance: For new political actors, adopting Twitter in high-penetration regions increases donations by 1–3.1%; effects are negligible for incumbents, highlighting reduced barriers to entry and heightened political competition (Petrova et al., 2020).

6. AI-Augmented Institutions and Future Directions

AI is positioned as a multifaceted enhancer:

- Participatory budgeting: In São Paulo’s Citizen Budget, AI addresses proposal overload (NLP clustering, automated technical screening), inclusion deficits (personalized recommendations to under-participating districts), deliberation facilitation (clustering, visualization, digital twins), and project monitoring (computer vision comparing “before/after” georeferenced imagery) (Sousa et al., 20 Sep 2025).

- Requirements for effective adoption: Successful AI deployment demands robust open data infrastructure, multidisciplinary teams, and regulatory frameworks to manage opacity, bias, and algorithmic governance (Sousa et al., 20 Sep 2025, Novelli et al., 2024).

- Ethics and risk: AI both mobilizes and fragments participation. It promotes inclusion, efficiency, and real-time feedback, but also heightens privacy risks, identity stereotyping, campaign manipulation, targeted misinformation (deepfakes, synthetic media), and challenges to legitimacy and public trust (Novelli et al., 2024). Safeguards—algorithmic fairness, transparency, and oversight—are critical.

- Modeling and metrics: Innovations such as divisiveness metrics complement consensus ranking to identify polarizing issues, enabling platforms to orchestrate targeted deliberation or information campaigns (Navarrete et al., 2022).

7. Challenges, Limitations, and Open Research Problems

Despite technological progress, enduring challenges remain:

- Usability vs. security: Protective mechanisms (e.g., CAPTCHA) can impede accessibility, while insufficient controls enable manipulation or defamation (Seigneur, 2010).

- Non-representativeness: Digital divides, self-selection, and voting loopholes (cookie-based systems) frequently lead to non-representative, easily manipulated participation data (Bojic et al., 2016, Emruli et al., 2011).

- Algorithmic and social biases: Structural inequalities (e.g., according to education, age), algorithmic opacity, and concentration of power (e.g., via network delegation cycles in liquid democracy) can distort the participatory process (De et al., 2024, Novelli et al., 2024).

- Translation to impact: Many platforms show limited real-world impact due to low engagement rates, insufficient integration with traditional democratic institutions, and a focus on minor issues rather than transformative policy decisions (Davies et al., 2020).

A significant future research direction is the integration of multidimensional AI and computational approaches not just for analysis, but for adaptive, participatory, and transparent orchestration of engagement, deliberation, and decision-making—while ensuring ethical guarantees, inclusivity, and continuous feedback loops for robust, legitimate political participation systems.