Non-Western Misinformation Practices

- Non-Western misinformation practices are diverse strategies for generating and countering false information shaped by state censorship, community trust, and local norms.

- Empirical studies reveal that these practices employ layered verification routines and moral economies to navigate digital divides and resource constraints.

- Actionable interventions include culturally grounded, participatory designs such as multimodal interfaces and social correction mechanisms that effectively address local challenges.

Non-Western misinformation practices constitute diverse, context-dependent strategies of generating, disseminating, and countering false information in information ecosystems characterized by state intervention, social hierarchies, digital divides, and local moral economies. Contrasting with the commonly studied Western paradigms, such practices are shaped by unique alignments of censorship, infrastructural politics, religious authority, technology adoption, and resource constraints. This article synthesizes empirical evidence from multi-country studies and participatory fieldwork to systematically describe non-Western misinformation practices, focusing on key mechanisms, institutional actors, sociotechnical methodologies, and actionable intervention principles.

1. Social, Political, and Cultural Drivers of Non-Western Misinformation

Non-Western misinformation environments are molded by an intersection of state power, social media architectures, cultural traditions, and community structures. In low-SES contexts such as Pakistan, participants rely on a predominantly feed-driven, social-mediated information ecosystem, rarely seeking news proactively and instead encountering it passively via TikTok, WhatsApp, or Facebook, with 22/30 reporting feed-driven exposure (Sohail et al., 8 Nov 2025). Algorithmic filtering narrows exposure to filter bubbles optimized for engagement over veracity.

In Iran, widespread platform bans (Telegram, Facebook, Twitter) and the prevalence of WhatsApp as a private network combined with the influence of religious authorities enable the propagation of both politicized narratives (“Western plot,” “enemies of Iran”) and religiously oriented remedies (e.g., shrine pilgrimages) (Madraki et al., 2020). State censorship in China and Cuba enforces strict content controls, domestic platform utilization, and sometimes complete information blackouts, redirecting information flows to analog means (USB “sneakernet” in Cuba) or to informal news smugglers in Bangladesh (Hakami et al., 22 Sep 2025).

Religious, communal, and traditional authorities exert epistemic and trust influence, as seen in Bangladesh and Iran, amplifying both the reach of misinformation (e.g., rumors endorsed by imams) and the community’s strategies for validation (Haque et al., 2020, Madraki et al., 2020). The empirical relationship between censorship and misinformation exposure is significant: (probability of frequent false-information encounters under heavy censorship) vs. under light censorship () (Hakami et al., 22 Sep 2025).

2. Verification Routines and Moral Economies

Verification practices in non-Western settings diverge from individualistic, search-based, or platform-driven fact-checking norms. Instead, users escalate verification via a layered “ecology of trust”:

- Immediate Intuitive Assessment: Visual/sensory heuristics (e.g., lip-sync quality, visual plausibility, gut feeling) filter obvious falsehoods (Sohail et al., 8 Nov 2025).

- Social Network Verification: Users consult elders, educated family, or religious leaders, granting epistemic authority to social ties. When those ties are misinformed, errors propagate along these trust networks.

- Legacy Media Cross-checks: Recognized as a “gold standard” (Geo News, ARY News in Pakistan), but considered too time-consuming (15–20 minutes/item) to practice routinely.

This process can be formalized as: with increasing cost and elapsed time for higher trust layers.

Similarly, decisions to share or withhold information are embedded in what has been termed a “moral economy of sharing.” Forwarding warnings is framed as protective and obligatory (“We send it so no one falls into trouble,” P12), whereas withholding unverified or potentially harmful material—especially religious content—is considered an ethical act (Sohail et al., 8 Nov 2025). Sharing is neither indiscriminate nor apolitical, but rather a communal calculus weighing harm avoidance and collective welfare.

3. Empirical Patterns and Typologies Across Linguistic and National Contexts

Cross-comparative studies reveal distinct thematic and root-cause distributions of misinformation:

- Topical Categories: Common across non-Western contexts are cures, prevention (public/individual), transmission, and politically or religiously colored narratives (e.g., “virus originated in Western biolabs,” “traditional remedies validated by religion”) (Madraki et al., 2020, Leng et al., 2020).

- Root Categories: Political (33–41%), Medical/Scientific, Religious/Traditional (notably 10.8% in Farsi/Iran vs. 2% in China), Pop Culture, Criminal, Other (Madraki et al., 2020).

- Channel Differences: Chinese misinformation skews toward origin myths and avoids criminal-fraud themes; Farsi in Iran is characterized by higher religious-traditional content; Bangladesh experiences rumor-driven communal violence enabled by platform centralization (98% Facebook reach).

Government censorship shapes not only the supply channels (forcing users onto WhatsApp in Iran or USB transfers in Cuba) but also the trust ecosystem and directionality of narratives (e.g., pro-government or anti-Western bias) (Hakami et al., 22 Sep 2025, Madraki et al., 2020). The interplay of platform constraints, religious/traditional authority, and legal-political environment uniquely configures each country’s misinformation landscape.

4. Role of Technology, Censorship, and Information Control Mechanisms

Censorship and misinformation are not merely antagonistic but often entwined, forming what has been called “information cocoons.” Tactics include keyword filtering, account shadowbanning, bot amplification of regime-friendly narratives, and algorithmic signal boosting of official sources (Hakami et al., 22 Sep 2025).

Quantitative analysis demonstrates that heavier censorship is associated with greater exposure to false information and more frequent attempts by users to evade censorship (43.8% reporting frequent evasion in high-censorship environments; 79.6% agreeing that censorship impairs fact verification). In China, astroturfing and orchestrated distraction campaigns manufacture apparent consensus, while in Venezuela, clustered “troll armies” dominate the attention graph around official hashtags.

Social media’s impact is conditional: it constrains misinformation only when public scrutiny is high (measured via administrative lawsuits and civic online engagement). For example, in Chinese local government GDP reporting, mandated WeChat adoption led to a statistically significant reduction in data fraud only in high-scrutiny cities (, ), while amplifying manipulation in low-scrutiny areas (Wang et al., 19 Jun 2025).

5. Participatory and Culturally-Grounded Intervention Methodologies

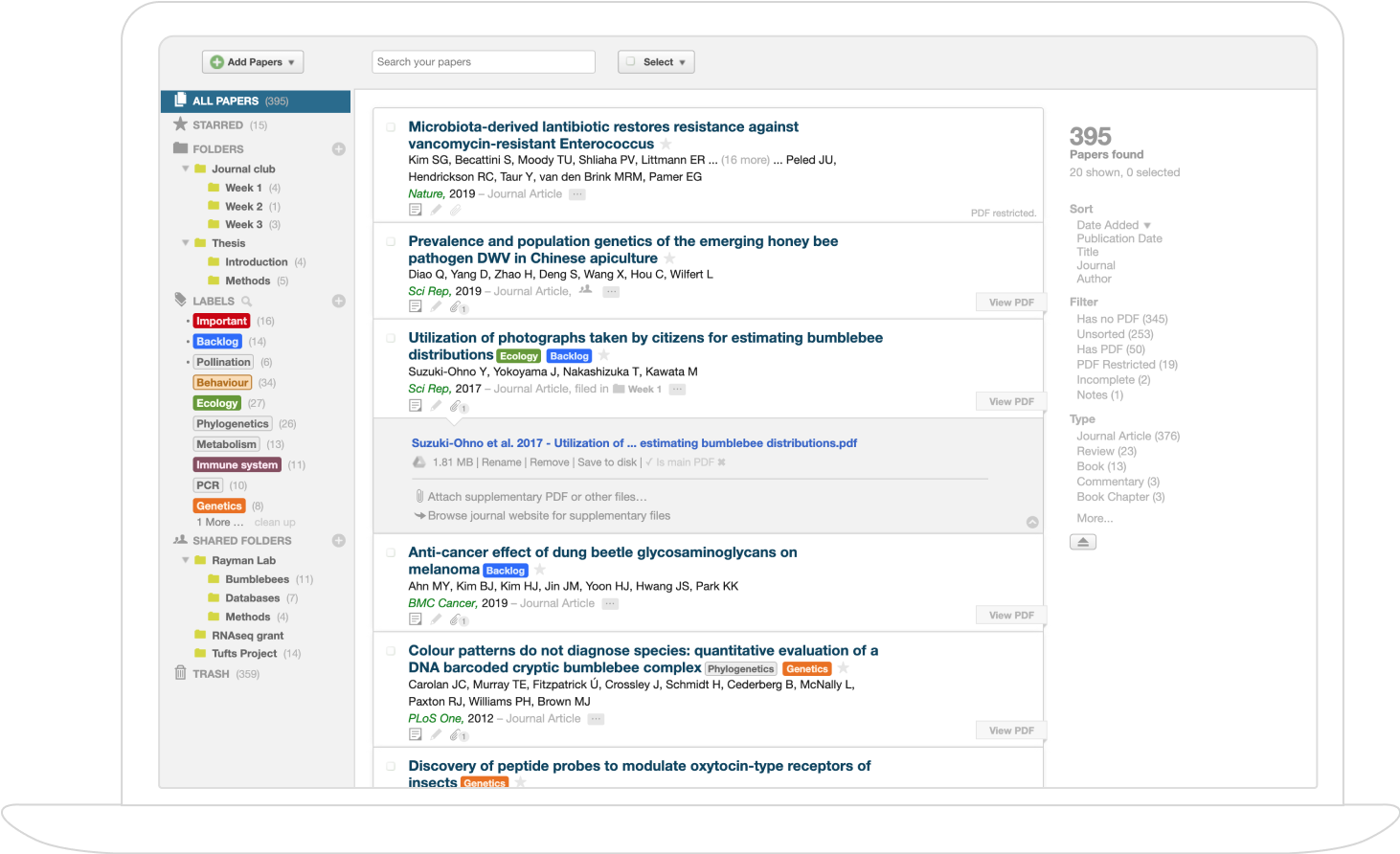

Successful interventions must recognize and embed themselves within users’ cultural, cognitive, and infrastructural realities. Participatory co-design in Pakistan established the following user-driven principles (Sohail et al., 8 Nov 2025):

- Voice-first and multimodal interaction, reflecting oral cultural preference.

- Transparent, actionable verdicts with explicit rationale.

- Social correction via shareable “proof objects” for use within trust networks.

- Empowerment-framed learning through scaffolded, non-competitive design.

- Navigation schemes aligned with habitual interface usage (e.g., scroll-vs-button).

The resulting Scaffolded Support Model integrates cognitive scaffolding (e.g., AI chat assistants for on-demand verification) with graduated skill acquisition (practice zones, daily tips, and gamified challenges). Usability studies confirm high acceptance (SUS 74.17; PSSUQ helpfulness ); the prototype “Pehchaan” operationalizes these principles.

Fact-checking in resource-constrained contexts like Bangladesh depends on voluntary, often under-resourced civil society organizations, and collaboration with journalists remains limited. There, the lack of local-language NLP tools, insufficient public data archives, and weak legal protections further undermine verification capacity (Haque et al., 2020). Practical recommendations include the development of Bengali NLP modules, browser-based rumor reporting, and media-literacy curricula oriented toward local heuristics and cognition.

6. Platform and Policy Interventions: Global and Local Strategies

Addressing the mutual reinforcement of misinformation and censorship, recent proposals include (Hakami et al., 22 Sep 2025):

- Transparency-First Content Warnings: Instead of removal, sensitive content is blurred with explicit explanations and evidence links, revealing the basis for intervention.

- Social-Verification Nudges: Platforms recommend verification with locally credible contacts or experts before sharing.

- Account Reputation Indicators: Designations flag known actors in coordinated influence operations, tailoring nudges to relationship strength.

Further, “plausibly deniable social platforms” propose dual-profile accounts, in which algorithmically generated benign content replaces sensitive material in the “public” view, enabling users to present credible, non-dissenting digital identities under coercion.

Effective global strategies require multi-language, multi-platform fact-checking coalitions, standardized metadata protocols (e.g., ClaimReview), and localization to counter cultural and religious hooks in misinformation. State-centric controls or Western-style fact-checking alone are insufficient; solutions must be adaptive, respecting both civic oversight and user epistemic agency (Madraki et al., 2020, Hakami et al., 22 Sep 2025, Sohail et al., 8 Nov 2025).

7. Synthesis, Contrasts, and Outlook

Non-Western misinformation practices are not peripheral variants of Western paradigms but constitute structurally distinct ecologies informed by social trust architectures, centralized or censored platform environments, and communal moral economies. State and quasi-state actors, religious leaders, and technology companies interact in context-specific ways, shaping both the content and pathways of false information. Localized, culturally resonant, and participatory interventions—underpinned by infrastructural investments in open data, platform transparency, and digital literacy—are empirically validated as more effective than top-down or externally imposed solutions. Studies consistently caution that the interplay of censorship and misinformation challenges the assumptions of both “open information” and “fact-checking” models, necessitating nuanced, context-aware frameworks for intervention and analysis.