Dual-Paradigm Taxonomy in Software Design

- Dual-paradigm taxonomy is a framework that categorizes design approaches into rational (plan-driven) and alternative (iterative, improvisational) paradigms based on epistemological differences.

- It employs detailed tables and mathematical representations to distinguish between systematic, phase-driven processes and adaptive, emergent methods in software design.

- The taxonomy informs research, practice, and education by guiding methodological choices and aligning development strategies with context-dependent project needs.

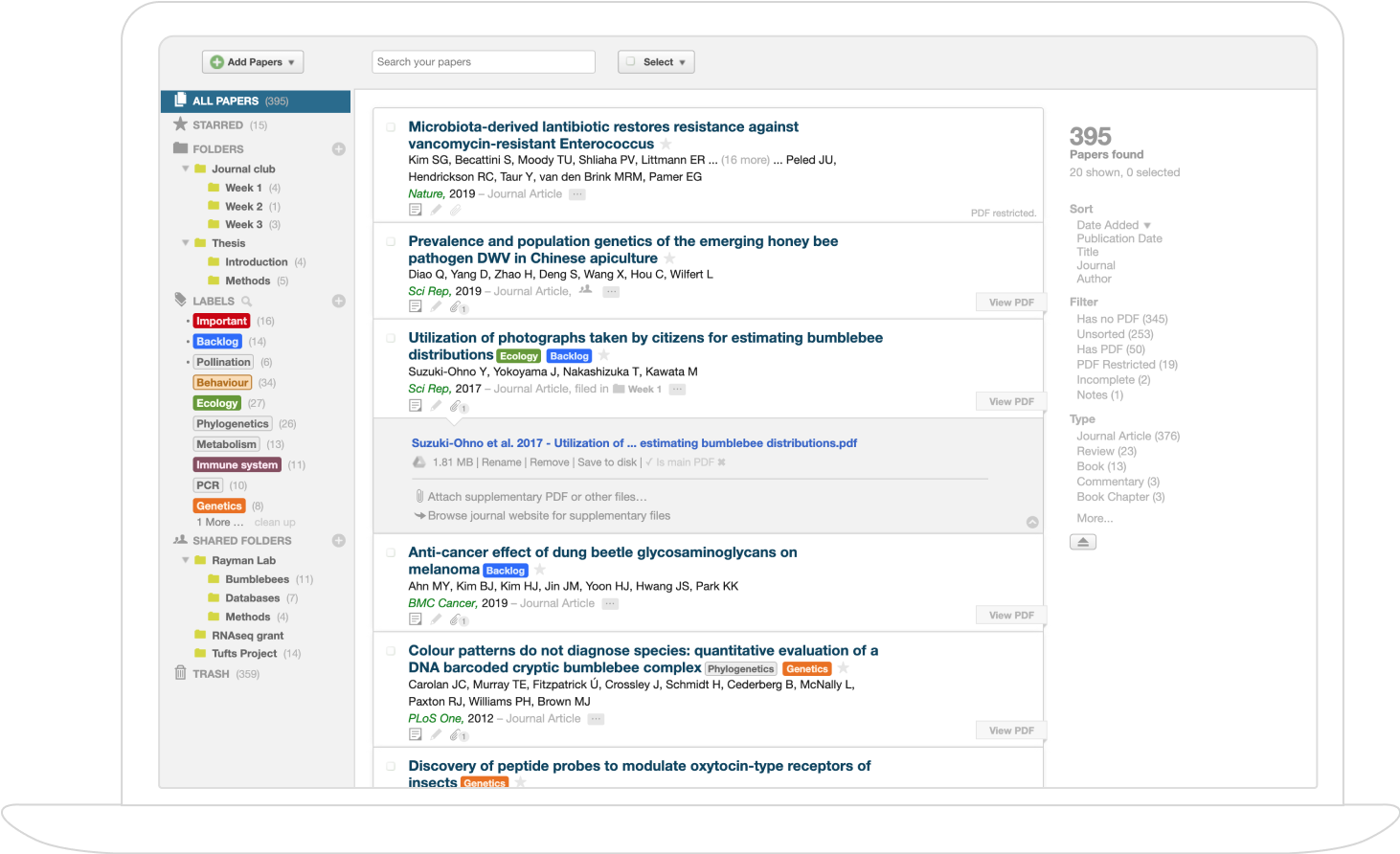

A dual-paradigm taxonomy delineates contrasting conceptual frameworks that organize a domain—typically illuminating fundamental methodological, epistemological, and practical dichotomies. In software design, as articulated in "The Two Paradigms of Software Design" (Ralph, 2013), the dual-paradigm taxonomy distinguishes between the Rational Design Paradigm and the Alternative Design Paradigm, each encoding distinct assumptions about the nature of problems, processes, knowledge, and roles. These perspectives inform not only taxonomic classification but the choice of development methodologies and the criteria for their evaluation.

1. Definitional Basis and Core Characteristics

The Rational Design Paradigm conceives software development as a methodical, plan-centered, and approximately rational process. It prescribes a sequence of phases (requirements, analysis, design, implementation) that aim to optimize the design candidate under known constraints. Core features include the Intuition/Deduction Thesis (IDT), reliance on clear and agreed-upon goals, and the use of planning models such as SDLC and FBS. Contrastingly, the Alternative Design Paradigm frames design as an amethodical, improvisational, and emotionally influenced process, where designers simultaneously frame problems and construct solutions. It emphasizes reflection-in-action and coevolution, with requirements considered ambiguous or emergent.

LaTeX representations summarizing the paradigmatic structures are as follows:

Rational Paradigm:

Alternative Paradigm: $\textbf{Alternative Paradigm:} \quad \text{Sensing (Context)} \leftrightarrow \text{Framing (Design Idea)} \rightarrow \text{Implementation}_{\text{Iterative %%%%1%%%% Improvisational}}$

2. Underlying Philosophical Commitments

The dual-paradigm dichotomy is underpinned by the philosophical opposition between rationalism and empiricism. The Rational Design Paradigm is rooted in rationalist epistemology, positing that optimal solutions can be deduced from intuition and clear problem statements. Its modus operandi is intellectual deduction. The Alternative Design Paradigm is rooted in empiricism, asserting that valid solutions are always contextually learned via sensory experience and iterative experimentation. Design knowledge in this paradigm emerges from embodied learning and feedback rather than abstraction or deduction.

This antagonism is reflected in contrasting approaches to requirements: rationalist approaches treat requirements as knowable; empiricist approaches treat them as continuously negotiated and provisional.

3. Components, Assumptions, and Taxonomic Tables

The taxonomy formalizes paradigms along epistemological, theoretical, and environmental axes. Tables in the source material specify these components:

| Paradigm | Epistemology | Design Model | Theory of Action | Methods | Environ. Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rational | Rationalism | Technical Problem-Solving | Planning Model | SDLC, FBS | Stable, knowable context |

| Alternative | Empiricism | Reflection-in-Action | Improvising Model | Amethodical, Agile | Ambiguous, emergent context |

Rational approaches assume decomposability and phase coupling, whereas alternative approaches model design as iterative emergence in unstable settings.

4. Implications for Research, Practice, and Education

Design research has predominantly been aligned with the rationalist paradigm, formalizing design as an optimization/search problem predicated on predetermined requirements. This alignment can obscure the realities of actual design contexts, especially for innovative or rapidly changing domains. Recognition of dual paradigms in research encourages richer theories such as Sensemaking-Coevolution-Implementation (SCI), which draws directly on empiricist principles and models design as a dynamic, coevolutionary process.

Practically, the rational paradigm underlies plan-driven, contract-centric methods suitable for fixed-requirement projects. The alternative paradigm informs flexible, adaptive practices, suitable for agile or experimental work. Educationally, the predominance of plan-driven curricula misses the improvisational and adaptive challenges typical in real-world engineering contexts, suggesting a need for curricular reform.

5. Comparative Analysis of Strengths and Limitations

A dual-paradigm taxonomy is essential for contextual matching between project circumstances and methodological approach. Rational paradigms offer systematicity, clarity, and process-organizational efficiency but are vulnerable to rigidity and requirement instability. Alternative paradigms accommodate uncertainty, foster adaptation and innovation, but risk process ambiguity and resistance from stakeholders seeking predictability.

Application suitability follows a context-dependent pattern: plan-driven approaches are best when requirements are static and context is stable; improvisational approaches thrive when requirements are emergent and environmental volatility is high.

6. Framework for Taxonomy Development and Theory Integration

The dual-paradigm taxonomy serves as a scaffolding for both domain mapping and methodological selection. It enables the classification of methods and theories by epistemological basis and design process structure. Two-axis frameworks can be constructed:

$\begin{array}{c|c} \textbf{Rational Paradigm} & \textbf{Alternative Paradigm} \ \hline \text{Planning Model} & \text{Improvising Model} \ \text{Plan-driven Methods (SDLC, FBS)} & \text{Amethodical, Agile/Iterative Methods} \ \text{Stable Environment} & \text{Unstable, Emergent Environment} \ \text{Deduction from Requirements} & \text{Sensemaking and Coevolution} \ \end{array}$

This taxonomy guides not only theoretical analysis but also practical methodology selection: choosing frameworks, adapting curricula, and informing the development of hybrid process models tailored to project context.

Summary

A dual-paradigm taxonomy in software design provides a rigorous mechanism for categorizing theoretical and practical approaches to system development. It highlights the deep epistemological and methodological divergences between rationalism (methodical, plan-driven, requirement-focused) and empiricism (amethodical, improvised, context-driven). By elucidating the strengths and limitations of each, it equips researchers, educators, and practitioners with an explicit framework for contextual decision-making. Rather than privileging one paradigm, such a taxonomy enables the selective and situationally appropriate application of process models, fostering methodological pluralism and realism in both research and practice.