Neural Tracking of Sustained Attention, Attention Switching, and Natural Conversation in Audiovisual Environments using Mobile EEG

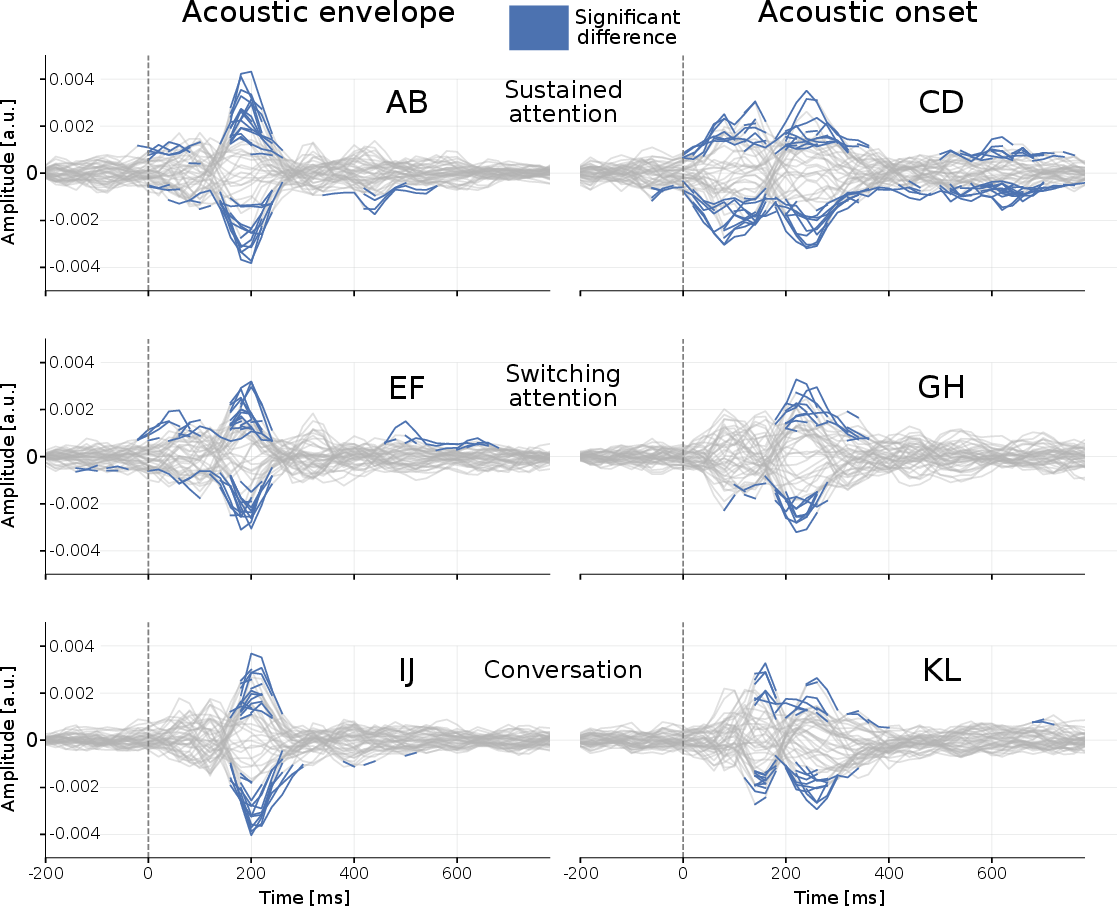

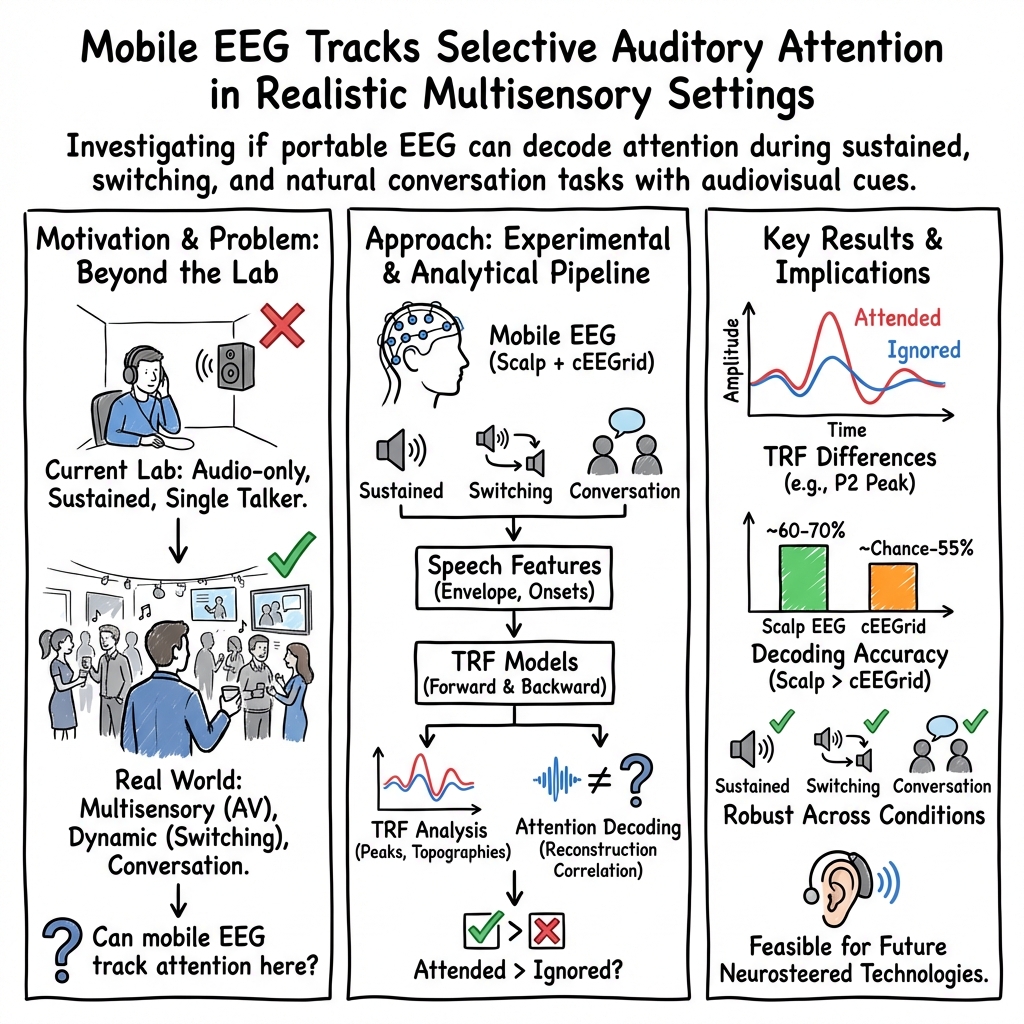

Abstract: Everyday communication is dynamic and multisensory, often involving shifting attention, overlapping speech and visual cues. Yet, most neural attention tracking studies are still limited to highly controlled lab settings, using clean, often audio-only stimuli and requiring sustained attention to a single talker. This work addresses that gap by introducing a novel dataset from 24 normal-hearing participants. We used a mobile electroencephalography (EEG) system (44 scalp electrodes and 20 cEEGrid electrodes) in an audiovisual (AV) paradigm with three conditions: sustained attention to a single talker in a two-talker environment, attention switching between two talkers, and unscripted two-talker conversations with a competing single talker. Analysis included temporal response functions (TRFs) modeling, optimal lag analysis, selective attention classification with decision windows ranging from 1.1s to 35s, and comparisons of TRFs for attention to AV conversations versus side audio-only talkers. Key findings show significant differences in the attention-related P2-peak between attended and ignored speech across conditions for scalp EEG. No significant change in performance between switching and sustained attention suggests robustness for attention switches. Optimal lag analysis revealed narrower peak for conversation compared to single-talker AV stimuli, reflecting the additional complexity of multi-talker processing. Classification of selective attention was consistently above chance (55-70% accuracy) for scalp EEG, while cEEGrid data yielded lower correlations, highlighting the need for further methodological improvements. These results demonstrate that mobile EEG can reliably track selective attention in dynamic, multisensory listening scenarios and provide guidance for designing future AV paradigms and real-world attention tracking applications.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper asks a simple, real‑world question: can we read someone’s focus of attention from their brain activity while they listen to people talking, even when the scene is complicated and includes video as well as sound? The authors recorded brain signals with a portable “mobile EEG” system while people listened to two talkers, switched attention between them, or followed a natural two‑person conversation with another voice talking off to the side. They show that attention can be tracked reliably in these realistic, multi‑talker, audio‑visual situations.

Key questions the study asked

Here are the main things the researchers wanted to find out:

- Can we detect which speaker a person is paying attention to using mobile EEG, not just big lab machines?

- Does attention tracking still work when people switch their attention from one talker to another?

- Does it work during a natural, unscripted two‑person conversation with video (faces, lip‑movements), not just clean, single‑speaker audio?

- Do small, around‑the‑ear EEG sensors (cEEGrid) work as well as regular scalp EEG sensors?

- How quickly can we tell who someone is listening to (using just a second or two of data vs. half a minute)?

How the study worked (in everyday language)

Think of EEG like very sensitive microphones that pick up tiny electrical “brain waves” through the scalp. The team used:

- 44 standard scalp electrodes (the classic cap)

- 20 small electrodes stuck around the ears (called cEEGrid), which are more discreet and wearable

They tested 24 adults with normal hearing (speaking Danish). People sat in a sound‑proof room and watched and listened to:

- Sustained attention: two video talkers in front; focus on just one the whole time and ignore the other.

- Switching attention: the same two talkers; switch focus twice during the clip when cued.

- Conversation attention: a natural two‑person conversation in front (video+audio) while a different single talker spoke from the side (audio only); focus either on the conversation or on the side talker.

Each trial lasted 3 minutes. To check people were paying attention, they answered content questions after each trial and rated how hard it felt.

How they analyzed the brain data:

- They used a method called a temporal response function (TRF). You can think of a TRF as a “brain echo” of the sound: when a sound feature happens (like a syllable starting), the brain responds a short time later. By lining up the speech and the EEG, you can learn the typical delay and shape of that response.

- “Forward model”: predict the EEG from the speech features.

- “Backward model”: reconstruct the speech beat or rhythm from the EEG and check how well it matches the real speech. If it matches better for the attended talker than the ignored one, you’ve found attention.

- “Correlation” is a simple score of how well two squiggly lines line up. Higher is better.

- “Decision window” is how many seconds of data you use to guess who the listener is attending to. Short windows mean faster, but harder, decisions.

They looked at two simple speech features:

- Acoustic envelope: the overall loudness pattern over time (like the “shape” of the speech).

- Acoustic onsets: moments when sounds start sharply (edges).

They also checked the timing of the best brain‑speech match (the “optimal lag”) to see when the brain responds most strongly after a sound event.

What they found and why it matters

These are the main results:

- People did the tasks well. They answered most questions correctly (about 85–89%). Switching attention and following conversations felt harder than focusing on one person, which fits real life.

- The brain shows clear attention signals across all conditions. A particular bump in the brain response called the “P2 peak” (a positive wave around 0.18–0.25 seconds after sound events) was reliably bigger for the attended talker than for the ignored one. This held in sustained attention, switching attention, and conversation scenes.

- Switching attention did not harm performance. The system’s ability to tell who was being attended to was about the same when people were switching focus as when they kept attention on one speaker. That’s good news for real‑world use, because we often shift our attention.

- Timing differences show realistic processing. The “optimal lag” (best brain‑speech delay) patterns changed depending on the task. During natural conversation, the peak timing range was narrower than in single‑talker video, suggesting the brain handles multi‑talker scenes with slightly different timing—likely due to the extra complexity of following a dialogue and using visual cues.

- Decoding attention worked above chance with scalp EEG. Using short windows as small as about 1 second up to about 35 seconds, the system could tell who the listener was focusing on better than a coin flip (roughly 55–70% accuracy, depending on window length and exact setup). Longer windows gave better accuracy.

- Around‑ear sensors (cEEGrid) were promising but not as strong yet. They showed weaker performance than the full scalp cap in this study, meaning more method improvements are needed for ear‑based, super‑portable systems.

Why this research matters (big picture)

This study moves attention decoding closer to everyday use:

- Realistic listening: It used natural video and audio with overlapping talkers and attention switches—closer to the “noisy party” problem real people face.

- Mobile technology: It showed that portable EEG can still track attention in these tougher situations.

- Path to smarter hearing devices: Future hearing aids or earbuds could use this kind of brain‑based attention tracking to automatically turn up the person you care about and turn down others, especially in noisy places.

In short, the study shows that our brains leave a detectable “fingerprint” of who we’re listening to, even in lively, video‑rich conversations. With further improvements—especially for small, around‑ear sensors—this could help build practical, attention‑aware hearing technology.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, consolidated list of concrete gaps and open questions the paper leaves unresolved, intended to guide future research:

- Generalizability beyond the cohort: Results are limited to 24 normal-hearing, native Danish speakers aged 23–51; effects in hearing-impaired listeners, older adults, non-native speakers, and other languages remain untested.

- Ecological validity: Recordings were conducted in a sound-proof room with seated, minimally moving participants; performance in realistic, noisy, and mobile “in-the-wild” environments (e.g., walking, head turns, public spaces) is unknown.

- Endogenous attention switching: All attention shifts were externally cued with visual markers; how well AAD works for spontaneous, self-initiated attention switches without cues is not assessed.

- Eye-tracking integration: Eye-tracking was collected but not analyzed; the relationship between gaze behavior, visual speech use, and decoding performance—especially during attention shifts—remains unexplored.

- Audiovisual contribution: The design confounds AV (front conversation with screens) versus audio-only (side talkers without screens); visual speech benefits were not isolated or systematically manipulated (e.g., congruent vs. incongruent lip movements).

- Ear-level acoustics: Near-ear microphones were recorded but not analyzed; how ear-level SNR, spatial cues, and reverberation influence TRFs and decoding accuracy is unknown.

- Overlapping speech within conversation: The paper does not quantify performance specifically during simultaneous speech segments or turn-taking within the two-talker conversation; tracking which conversational talker is attended at each moment remains unresolved.

- Intra-conversation attention decoding: Although extra conversation trials were collected to enable intra-conversation analysis, no results are reported on decoding attention to one talker versus the other within the conversation.

- Latency shifts across tasks: A consistent ~20 ms delay in P1/N1 latencies (SwitAC, ConvAC vs. SustAC) is observed but not mechanistically explained; contributions from task demands, multisensory integration, gaze shifts, or cognitive load need targeted testing.

- Narrower optimal-lag peaks in conversation: The observed narrower peak for ConvAC in optimal lag analysis lacks a clear interpretation; whether it reflects task complexity, multi-talker competition, or AV integration should be probed.

- Short-window decoding limits: Scalp EEG classification remains ~55–70% with windows down to ~1.1 s, likely insufficient for practical hearing devices; strategies to raise accuracy at sub-second timescales (features, algorithms, sensor configurations) are needed.

- Real-time/online decoding: All analyses are offline; latency budgets, online model adaptation, and closed-loop operation with hearing devices are untested.

- cEEGrid performance: cEEGrid correlations and classification are weak; it is unclear whether improved referencing, channel selection, placement optimization, individual calibration, or advanced preprocessing can reliably elevate ear-EEG performance in AV, multi-talker tasks.

- Subject-specific vs. generic models: The impact of individualized parameter tuning (often used with cEEGrid) versus generic models on performance and fairness was not evaluated.

- Feature space limitations: Only acoustic envelope and onsets were used; richer speech features (prosody, pitch/F0, phonetic/linguistic features, semantic surprisal) and visual features (lip kinematics, face motion) were not tested, nor were multimodal decoders.

- Algorithmic comparisons: Boosting-based mTRF was the sole modeling approach; comparative evaluation versus ridge regression, state-space models, time-adaptive decoders, or deep learning (e.g., CCA variants, CNN/RNN/Transformer) is missing.

- Source localization: TRF topographies were shown but no source localization was performed; linking components (e.g., P1/N1/P2, N400) to cortical generators could clarify mechanisms.

- Negative-lag components: Although lags from −1 s to +1 s were fit, anticipatory (negative-lag) components were not analyzed; potential predictive coding effects remain unexplored.

- Behavioral–neural linkage: Self-rated difficulty and comprehension accuracy were collected, but their quantitative relationships to neural metrics (TRF amplitudes, reconstruction correlations, classification accuracy) were not examined.

- Inter-individual variability: The distribution of performance across subjects, factors driving variability (e.g., attention strategies, visual acuity, familiarity), and robustness to cross-subject generalization remain under-characterized.

- Test–retest reliability: Stability of TRFs and decoding performance across sessions/days was not assessed.

- Statistical power and robustness: Some effects (e.g., cEEGrid) are marginal (p < 0.1); a priori power analysis, pre-registration, and replication would strengthen claims.

- Visual fixation confound: ConvAC required gaze shifts for conversation but central fixation for side talkers; matched visual control conditions are needed to disentangle effects of gaze versus auditory attention.

- Spatialization fidelity: Loudspeaker-based spatialization without individualized HRTFs may limit ecological spatial cues; the impact of higher-fidelity spatial rendering on AAD is unknown.

- Motion artifact resilience: The pipeline relies on manual ICA and bandpass filtering; automated, real-time artifact handling and robustness to motion (facial muscles, jaw movement, walking) are untested.

- Channel-level diagnostics: It is unclear which scalp or cEEGrid channels contribute most to decoding; systematic channel selection or learned spatial filters could optimize sensor configurations.

- Pipeline reproducibility: Manual ICA decisions introduce subjectivity; standardized, automated preprocessing suitable for real-time use is needed.

- Language specificity: Using Danish enables novel assessment, but cross-language generalization (phonotactics, prosody, lexical structure) is untested; multilingual comparisons are needed.

- Stimulus content control: Topic complexity and linguistic structure differ between single-talker TV excerpts and the podcast; without controlling content, semantic/structural confounds may affect TRFs.

- Hardware synchronization: LSL-based synchronization was used, but residual timing jitter across devices was not quantified; timing uncertainty could affect TRF estimates.

- Data and code availability: The “novel dataset” is introduced, but plans for public release, documentation, and reproducible code are not specified; open access would enable validation and benchmarking.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The findings and methods in this paper can be put to use right away in research and development, usability testing, and methodology standardization. The following applications are deployable with current tools and data, given access to mobile EEG systems and standard analysis software.

- Neural attention tracking benchmarks for realistic AV listening

- Sectors: academia, hearing-aid/hearables R&D, audio software

- What to do: Use the paper’s audiovisual (AV) sustained, switching, and conversation paradigms—together with TRF-based pipelines—to benchmark selective attention decoding (SAD/AAD) under naturalistic, multi-talker conditions. Compare models using envelope vs onset features, decision-window lengths (1.1–35 s), and optimal-lag profiles.

- Tools/workflows: Eelbrain TRF boosting; LabStreamingLayer (LSL) synchronization; mobile EEG (e.g., Smarting Pro X); AV stimulus design replicating frontal talkers and side interferers; leave-one-trial-out CV to avoid within-trial leakage.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to mobile EEG equipment; controlled room and calibrated loudspeakers; sufficient trial durations; the dataset from the paper (if released) or analogous AV stimuli; generalization beyond Danish requires validation.

- Product prototyping and usability testing for attention-guided audio

- Sectors: hearing aids, hearables, conferencing systems, UCaaS

- What to do: Conduct in-house lab tests that route or prioritize an attended talker’s audio while logging EEG-based attention markers (e.g., P2 differences, reconstruction correlations). Verify robustness to attention switches using the paper’s switching paradigm.

- Tools/workflows: Real-time or pseudo-real-time TRF tracking with ~5–35 s windows; gated audio mixing based on correlation deltas between attended vs ignored stimuli; synchronized gaze logging for ground-truth.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Current scalp-EEG achieves ~55–70% accuracy, which is above chance but not product-grade; cEEGrid performance is lower and needs further improvement; tests best run in controlled environments.

- Experimental design templates for naturalistic multisensory attention studies

- Sectors: cognitive neuroscience, HCI, human factors

- What to do: Adopt the paper’s AV tasks (sustained, switching, conversation) as templates for studying multisensory attention, gaze behavior, and listening effort. Include balanced sex/position of speakers and unbiased stimulus randomization.

- Tools/workflows: AV stimulus curation with natural speech, overlapping talkers, and visual cues; trial-level comprehension questions; listening/understanding difficulty ratings; optimal-lag scans (−600 to 600 ms) to localize informative latency windows.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Eye-tracking integration is recommended (recorded in the study but not analyzed); replication requires careful synchronization and calibration.

- Objective listening effort and attention markers for research cohorts

- Sectors: audiology research, clinical research (pilot), ergonomics

- What to do: Use P2 and late components (including N400-like effects) from forward TRFs, plus reconstruction correlations, as objective markers of selective attention and task difficulty across conditions. Compare sustained vs switching vs conversation tasks.

- Tools/workflows: TRF peak analysis with mass-univariate statistics and TFCE corrections; envelope vs onset features; topographic mapping; optimal-lag profiling to probe temporal dynamics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Currently validated in normal-hearing adults; not yet a diagnostic; moderate group sizes recommended to ensure statistical power.

- Methodological guidance and pre-standards for AAD evaluation

- Sectors: standards bodies, research consortia, industry labs

- What to do: Incorporate guidance from this study into internal/external test protocols—e.g., include AV stimuli, switching trials, conversation trials; use leakage-safe CV; report decision-window sensitivity; report cEEGrid vs scalp performance.

- Tools/workflows: Shared evaluation sheets with required metrics (attended vs ignored correlations, classification accuracy across window sizes, optimal-lag curves).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Formal standards will require broader inter-lab validation and population diversity (age, hearing status, languages).

- Classroom and group-discussion pilot measurements (controlled settings)

- Sectors: education research, EdTech prototyping

- What to do: Pilot mobile-EEG monitoring of selective attention during small-group discussions to evaluate engagement and the effect of visual cues, using scalp EEG in controlled, low-noise classrooms.

- Tools/workflows: TRF-based tracking; short decision windows (~5–15 s) for session-level trends; comprehension checks; difficulty self-reports.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Feasible as a research pilot only; ambient noise and movement reduce signal quality; cEEGrid performance currently insufficient for robust decoding in the wild.

- Comparative feature engineering for AAD

- Sectors: machine learning for neurotech

- What to do: Benchmark envelope vs onset features, and hybrid representations, using this paper’s pipeline to optimize feature mixes per condition (sustained vs switching vs conversation).

- Tools/workflows: Feature ablations; basis-function TRFs; model selection driven by lag-specific performance; subject-independent vs fine-tuned models.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires access to raw EEG and stimuli; performance gains must be validated across datasets.

Long-Term Applications

These applications are feasible with further research, algorithmic advances, sensor improvements (esp. ear-EEG/cEEGrid), field validation, and regulatory/ethical frameworks.

- Neuro-steered hearing aids and hearables robust to attention switches

- Sectors: healthcare (audiology), consumer hearables

- What it could become: Real-time attention-controlled beamforming and noise suppression that tracks the attended talker in multi-talker, AV-rich environments; robust to rapid attention shifts.

- Tools/products/workflows: Ear-EEG arrays (improved cEEGrid/in-ear sensors), short-window decoding (~1–3 s), on-device inference; multimodal fusion (EEG + eye/gaze + acoustic scene analysis).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Significant uplift in classification accuracy with ear-EEG; generalization to hearing-impaired populations; low-latency, low-power embedded implementations; clinical validation and regulatory approval.

- Attention-aware conferencing and telepresence

- Sectors: enterprise software, UCaaS, collaboration tools

- What it could become: Personalized audio mixes that elevate the user’s attended remote speaker; dynamic talker highlighting/auto-framing guided by attention and gaze.

- Tools/products/workflows: EEG-enabled headsets/earbuds; integration with beamforming mics and speaker diarization; privacy-preserving, on-device processing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Comfortable, unobtrusive sensors; privacy and consent frameworks for neurodata; robust decoding in varied acoustic and motion conditions.

- AR/VR attention-driven spatial audio and UX

- Sectors: XR, gaming, training simulation

- What it could become: Adaptive spatial audio that amplifies the currently attended virtual avatar or instructor; cognitive-load-aware training scenarios.

- Tools/products/workflows: Tight integration of EEG with head and eye tracking; real-time TRF-style decoders; adaptive scene design based on optimal-lag “attention windows.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sensor fusion robustness during motion; hardware miniaturization; developer toolkits and content standards.

- Clinical diagnostics and monitoring for attention and auditory processing

- Sectors: healthcare (neurology, psychiatry, audiology)

- What it could become: Ecologically valid, AV-based assessments for auditory processing disorder (APD), ADHD, or central auditory dysfunction using P2/N400-like TRF markers and attention-switching performance.

- Tools/products/workflows: Normative databases by age/hearing status/language; clinic-friendly ear-EEG; standardized AV test batteries and scoring.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Large-scale validation; sensitivity/specificity studies; reimbursement pathways and clinical guidelines; language and cultural generalization.

- Adaptive education platforms responsive to attention

- Sectors: EdTech

- What it could become: Real-time adaptation of instructional media (pace, modality, turn-taking) based on group or individual attention decoding during discussions or lectures.

- Tools/products/workflows: Attention dashboards from short windows; privacy-by-design aggregated metrics; teacher-in-the-loop interfaces.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ethical, consent, and privacy safeguards; robustness in noisy, mobile contexts; equity and bias considerations across learners.

- Automotive and safety-critical auditory management

- Sectors: automotive, control rooms, aviation, public safety

- What it could become: Systems that prioritize alerts or communications the user is attending to and throttle competing streams during high workload; attention-switch-aware alert scheduling.

- Tools/products/workflows: Ear-EEG embedded in headsets/helmets; integration with auditory scene analysis; cognitive load estimation using TRF features.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Motion-robust sensing; fail-safe designs; certification for safety-critical use.

- Personalized media and broadcast experiences

- Sectors: media/streaming, sports broadcasting, accessibility

- What it could become: Listeners seamlessly prioritize languages/commentary tracks or speakers they attend to; attention-guided dynamic mixing for multi-speaker content.

- Tools/products/workflows: Consumer-grade neuro-sensing in earbuds; on-device attention decoding; content-side multi-stem audio publishing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consumer acceptance; battery and comfort constraints; standards for multi-stem content and device interop.

- Cognitive wellness and fatigue monitoring in complex listening

- Sectors: mental health, workplace wellness

- What it could become: Longitudinal tracking of listening effort and attentional resilience using TRF markers (e.g., P2 amplitude/latency shifts, N400-like effects) during everyday conversations.

- Tools/products/workflows: Passive monitoring with ear-EEG; personalized baselines; privacy-preserving analytics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear clinical/occupational value propositions; robust baselining across contexts; strong privacy protections.

- Standardized AAD evaluation suites and open datasets

- Sectors: academia, industry consortia, standards

- What it could become: Public benchmarks covering AV sustained, switching, and conversation tasks across languages and hearing statuses; common protocols and metrics (decision-window curves, optimal-lag profiles).

- Tools/products/workflows: Reference toolchains (TRF boosting, lag scans, classification); dataset governance and sharing frameworks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-institutional collaboration; funding and consent for broad data sharing; harmonization of hardware and protocols.

Notes on cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies:

- Sensor readiness: Current scalp EEG provides above-chance decoding; cEEGrid/ear-EEG needs improved signal quality and algorithms to be viable outside labs.

- Algorithmic maturity: Short-window, real-time decoders with high accuracy remain an active research area; multimodal fusion (EEG + gaze + acoustics) is likely necessary.

- Generalization: The study used normal-hearing adults and Danish speech in controlled rooms; broader demographics, hearing losses, languages, and real-world conditions must be validated.

- Ethics and privacy: Any application decoding attention from neural data requires rigorous consent, on-device processing where possible, and strong data protection.

- User experience: Comfort, battery life, and unobtrusiveness are crucial for daily-life use; calibration time should be minimized.

Glossary

Acoustic envelope: Refers to the representation of sound that signifies how the loudness of an audio signal changes over time. "Reconstruction accuracy (i.e., correlations between reconstructed and actual speech) from the backward model showed significantly higher correlation for attended speech than for ignored speech for scalp electrodes with both speech features, while for cEEGrid electrodes, significance appeared only for acoustic onsets."

Attention classification: The process of determining whether the focus of auditory attention is on the attended or ignored speech based on neural signals. "Attention classification analysis determined the successful decoding of attended versus ignored speech."

cEEGrid electrodes: A flexible array of electrodes placed around the ear, validated for capturing auditory attention signatures. "For cEEGrid electrodes, separation between attended and ignored speech started after \SI{100}{\milli\second} and peaked around \SI{250}{\milli\second}, differing from previous data."

Gammatone (GT) filtering: A method used in processing auditory signals emulating human auditory perception, creating a representation useful for speech feature extraction. "Gammatone (GT) filtering of the presented audio, with 128 frequency bands spaced according to the equivalent rectangular bandwidth scale."

Independent component analysis (ICA): A computational method for separating a multivariate signal into additive, independent components, commonly used for artifact removal in EEG data. "Independent component analysis (ICA) using the extended infomax algorithm was then applied with 20 components for scalp EEG and 9 components for cEEGrid EEG."

Optimal lag analysis: A technique used for determining the time delay at which the relationship between two time series signals (like EEG and an auditory stimulus) is strongest. "Optimal lag analysis found the lag-intervals with the highest reconstruction/prediction correlations."

Temporal response function (TRF): A linear model measuring brain responses to continuous auditory stimuli over time, used to track attention or decode neural data. "Neural tracking of speech was modeled using the temporal response function (TRF), a linear finite impulse response model."

Temporal response functions (TRFs) modeling: A method used to describe how the brain responds to different time-lagged versions of a stimulus feature. "Analysis included temporal response functions (TRFs) modeling, optimal lag analysis, selective attention classification."

Threshold-free cluster enhancement: A statistical method improving the sensitivity and specificity of cluster-based tests, often used in neuroimaging analysis. "Mass-univariate statistics were employed using independent samples t-tests, with threshold-free cluster enhancement."

Working memory components: Cognitive processes that temporarily hold and manipulate information, crucial in language processing and auditory attention tasks. "Cluster revealed significant differences at P2 and around 400 ms, consistent with the N400 associated with higher-order linguistic processing and working memory capacity."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.