A Mathematical Theory of Payment Channel Networks

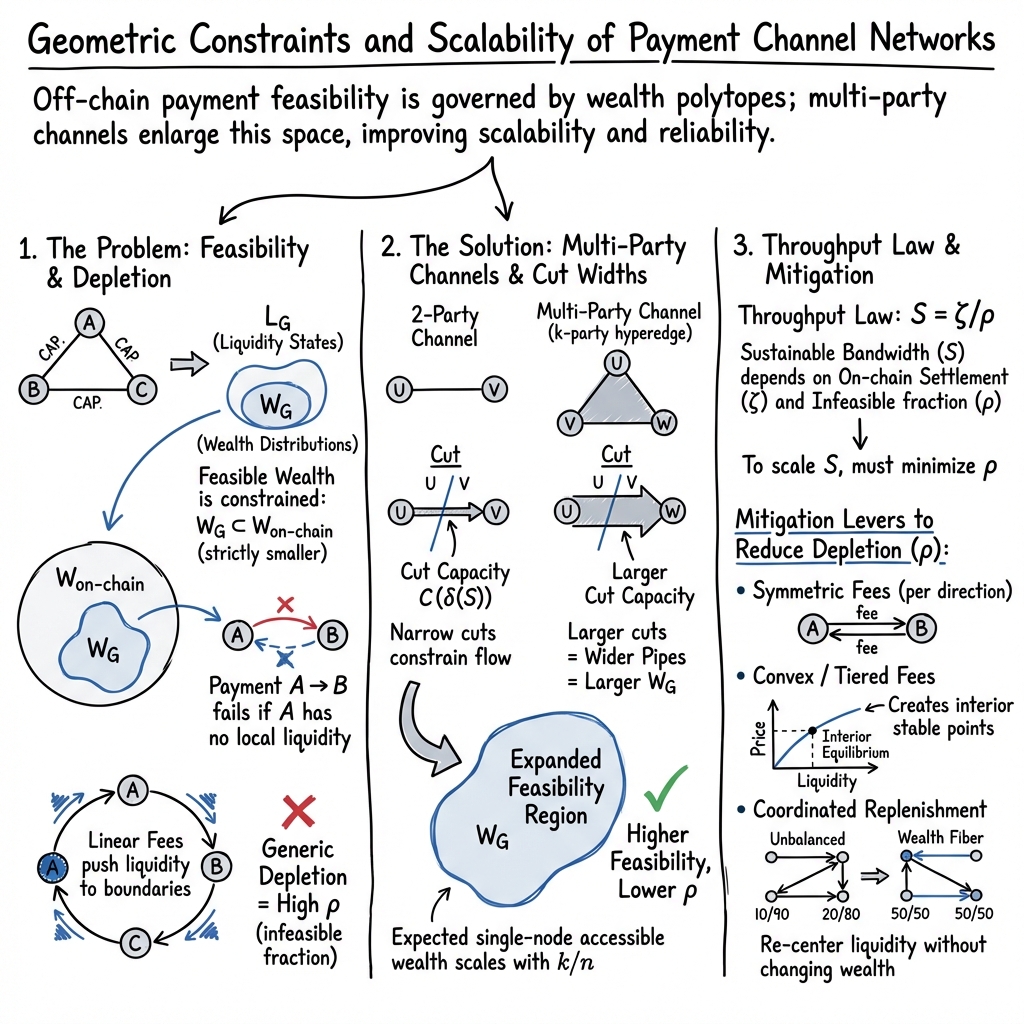

Abstract: We introduce a geometric theory of payment channel networks that centers the polytope $W_G$ of feasible wealth distributions; liquidity states $L_G$ project onto $W_G$ via strict circulations. A payment is feasible iff the post-transfer wealth stays in $W_G$. This yields a simple throughput law: if $ζ$ is on-chain settlement bandwidth and $ρ$ the expected fraction of infeasible payments, the sustainable off-chain bandwidth satisfies $S = ζ/ ρ$. Feasibility admits a cut-interval view: for any node set S, the wealth of S must lie in an interval whose width equals the cut capacity $C(δ(S))$. Using this, we show how multi-party channels (coinpools / channel factories) expand $W_G$. Modeling a k-party channel as a k-uniform hyperedge widens every cut in expectation, so $W_G$ grows monotonically with k; for single nodes the expected accessible wealth scales linearly with $k/n$. We also analyze depletion. Under linear, asymmetric fees, cost-minimizing flow within a wealth fiber pushes cycles to the boundary, generically depleting channels except for a residual spanning forest. Three mitigation levers follow: (i) symmetric fees per direction, (ii) convex/tiered fees (effective flow control but at odds with source routing without liquidity disclosure), and (iii) coordinated replenishment (choose an optimal circulation within a fiber). Together, these results explain why two-party meshes struggle to scale and why multi-party primitives are more capital-efficient, yielding higher expected payment bandwidth. They also show how fee design and coordination keep operation inside the feasible region, improving reliability.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper builds a simple, geometric way to understand how the Lightning Network (a fast payment system built on Bitcoin) actually works with limited “balancing” between users. It explains why some off-chain payments fail, why channels often drain to one side, and how multi-party channels (where more than two people share one big channel) can make the system more reliable and scale to more payments.

In short: it gives rules for when a payment can go through off-chain, shows why two-party channels struggle to scale, and argues that multi-party channels and better fee designs can make off-chain payments both more reliable and more efficient.

What questions does the paper ask?

- When is a payment in the Lightning Network actually possible?

- How do the network’s structure and channel balances limit which payments can succeed?

- Why do channels tend to get “drained” (one side has almost all the money)?

- How much can off-chain payment networks scale compared to on-chain transactions?

- How do multi-party channels (coinpools) change these limits?

- Which fee and coordination strategies help keep payments reliable?

How does the paper study the problem?

Think of the Lightning Network like neighborhoods connected by pipes that carry water (money). Each pipe (channel) has a maximum size (capacity), and the water inside it must be split between the two neighbors who share it. You can push water around the pipes to pay someone, but you can’t magically create more water, and it can’t leave a pipe unless you use the on-chain Bitcoin system.

The paper treats the whole network as a big “shape” of all the possible ways money can be arranged:

- Liquidity states “L_G”: all the ways the money can be split across all channels, obeying “conservation of liquidity” (the total in a channel stays constant unless you do an on-chain change).

- Wealth distributions “W(C,n)”: all the ways the total money could be distributed among the n users if there were no off-chain limits (like how many ways you can share C coins among n people).

- Feasible wealth “W_G”: the subset of those distributions that you can actually reach using only the existing channels (no on-chain changes). This depends on the network’s shape and capacities.

Two key ideas make this easier to picture:

- Cuts: Imagine drawing a line that divides the network into two groups S and not-S. The “cut capacity” is the total size of the channels crossing that line. The paper shows the total money that group S can have must fit inside an interval whose width equals that cut capacity. Bigger cut capacity means more freedom to move money and fewer failures.

- Max-flow/min-cut: The maximum amount you can push from person A to person B equals the capacity of the narrowest “bridge” (cut) on the way. If your payment is larger than that narrowest bridge, it fails.

To compare designs:

- Two-party channels are like simple pipes between pairs.

- Multi-party channels (k-party channels, coinpools) are like big shared tanks connecting k people at once. The paper models these as “hyperedges” and shows they make many cuts wider, which enlarges W_G (more wealth distributions are feasible) and increases the number of payments that can succeed.

The paper also uses simple probability and sampling (like rolling dice many times) to estimate how often payments will fail and how much different designs help.

What did the paper find?

- A simple throughput law for off-chain payments:

- If some payments are infeasible, you must use the blockchain (on-chain) to rearrange money or change channels. Suppose the blockchain can do ζ transactions per second and the fraction of off-chain payment attempts that are infeasible is ρ. Then the sustainable off-chain payment rate is:

- S = ζ / ρ

- To reach very high payment rates (like Visa-level), ρ must be extremely small. With Bitcoin’s on-chain limit (about 7 tx/s), you’d need ρ around 0.015% to support ~47,000 payments per second. That’s a very tough target for two-party channel networks.

- If some payments are infeasible, you must use the blockchain (on-chain) to rearrange money or change channels. Suppose the blockchain can do ζ transactions per second and the fraction of off-chain payment attempts that are infeasible is ρ. Then the sustainable off-chain payment rate is:

- Two-party channels limit reliability and scaling:

- Many possible ways to distribute money among users aren’t reachable off-chain (they’re outside W_G). That means some payments will fail no matter how smart the routing is.

- As payment amounts grow, failures rise because the “narrowest bridges” (cuts) get in the way.

- Equal-sized channels maximize the number of possible network states, but even then, two-party designs struggle to make ρ small enough.

- Multi-party channels widen cuts and improve capital efficiency:

- Replacing some two-party pipes with k-party “shared tanks” increases the expected width of cuts. That makes more wealth distributions feasible and lowers ρ.

- For a single user, the expected accessible wealth grows roughly like k/n. In other words, if k increases, each person can reach a larger fraction of the network’s money without going on-chain.

- Result: Multi-party channels increase the set W_G and make more payments feasible, boosting off-chain bandwidth.

- Why channels get “depleted” and what to do about it:

- With standard linear, asymmetric fees (fees differ per direction and increase proportionally with amount), cost-minimizing routing tends to push flows to extremes, draining channels and leaving only a sparse core structure (a “spanning forest”).

- Three mitigation ideas:

- Symmetric fees per direction: simple and reduces bias, but many operators might not like it.

- Convex/tiered fees: make larger payments cost more per unit to discourage pushing everything along one path; this helps local flow control but can conflict with source routing unless real-time liquidity is known.

- Coordinated replenishment: nodes jointly choose circulation patterns to rebalance within a feasible region, matching participants’ preferences while staying inside W_G.

- A note on credit:

- If channels allowed negative balances (credit), you could reach any wealth distribution off-chain. But that requires trust and breaks the “trustless” design many people want. The geometry shows why trustless systems face these hard limits.

Why does this matter?

- It explains a core limitation of two-party payment channel networks: they can’t make almost all payments feasible unless the network constantly uses on-chain transactions. That caps off-chain scaling.

- It shows a path forward: multi-party channels (coinpools) and smarter fee policies widen the feasible region W_G, reduce failures, and make more payments possible without going on-chain.

- It gives operators and protocol designers concrete levers:

- Use more multi-party primitives to make the network more capital-efficient.

- Design fees to avoid pushing flows to extremes and causing depletion.

- Coordinate rebalancing so the network stays inside the feasible region (fewer failures).

Bottom line

- Off-chain payments succeed only if the post-payment wealth distribution stays inside the network’s feasible region W_G.

- Two-party channel networks make W_G too small, so a noticeable fraction of payments are inevitably infeasible, limiting scaling.

- Multi-party channels strictly enlarge W_G by widening cuts, making more payments feasible and increasing off-chain bandwidth.

- Careful fee design and coordination can keep the network operating inside the feasible region, reducing depletion and failures.

- If we want off-chain payments at very large scale, we should embrace multi-party channels and smarter operations, not rely solely on two-party channels.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed so future researchers can act on it:

- Full characterization of the feasible wealth polytope: Are the cut-interval constraints both necessary and sufficient to describe ? Provide a complete, minimal inequality system for and prove equivalence.

- Closed-form and bounds for : Derive analytic formulas or tight upper/lower bounds for for general graph classes (trees, regular graphs, sparse expanders, hub-and-spoke, heterogeneous capacities), and identify parameters that dominate .

- Topology design for maximal feasibility: Formulate and solve (or approximate) the optimization problem of choosing (given and constraints like sparsity, degree bounds, privacy) to maximize or minimize .

- Robustness of the throughput law : Quantify the on-chain cost per infeasible payment (often more than one transaction), include background on-chain activity (opening/closing/splicing/anchors), and refine the law under realistic settlement workflows.

- Empirical calibration of and on LN: Develop a privacy-preserving measurement methodology to estimate the fraction of topologically infeasible payments and relative feasible volume on the live Lightning Network, accounting for jamming and probing noise.

- Scalable membership oracles for : Replace ILP with faster algorithms (e.g., multi-source/multi-sink flows or precomputed cut constraints) to decide at LN scale, with provable complexity and error bounds.

- Validation of Dirichlet Rescale sampling: Prove that the Dirichlet Rescale Algorithm produces uniform samples over the discrete composition set and quantify variance and convergence rates for Monte Carlo estimates of and .

- LN-specific constraints in the model: Integrate HTLC slot limits, channel reserves, dust limits, timelocks, min/max CLTV deltas, in-flight HTLCs, base/ppm fees, and policy constraints into , , and , and quantify how they shrink feasibility.

- Formal depletion results: Rigorously prove (or refute) that linear asymmetric fees push cycles to the boundary and generically deplete channels to a residual spanning forest; precisely define and analyze “wealth fibers” and optimal circulations under different fee regimes.

- Fee mechanism design: Specify and analyze convex/tiered fee functions that achieve local flow control while preserving source routing and privacy; determine required protocol changes and their impact on feasibility () and reliability.

- Coordinated replenishment protocols: Design decentralized, privacy-preserving algorithms to compute and execute near-optimal circulations that align with participants’ preferences; address incentive compatibility and robustness to strategic behavior.

- Generalization of k-party results beyond uniform hypergraphs: Prove cut-width monotonicity () and accessible-wealth scaling under heterogeneous capacities , nonuniform membership distributions, correlated structures, and adversarial settings.

- Operational constraints of k-party channels: Analyze real protocol designs (channel factories/coinpools), dispute resolution, exit paths, on-chain footprint, watchtowers, and failure modes; quantify how these constraints reduce effective cross-cut capacity vs. the idealized model.

- Validity of “shift all across the cut” assumption: Identify internal constraints (per-participant output limits, exit costs, timelock structures, fragmentation) that prevent moving full capacity across cuts; model the resulting effective capacity.

- Source routing vs. geometric improvements: Quantify how increases in cut capacities translate into end-to-end success rates, latency, and fees under source-routed, path-based payments with multipath payments (MPP) and partial information.

- Realistic topology models: Replace uniform random graph/hypergraph assumptions with models fitted to LN (heavy-tailed degree distributions, hubs, multi-edges, heterogeneous capacities), and recompute , expected cut capacities, and under those models.

- Structure of solution fibers : Characterize when is tight, describe integer-feasible structures, and provide constructive methods to recover a specific realizing a feasible .

- Impact of MPP and liquidity splitting: Formalize how multipath payments modify feasibility conditions and relative to single-path flows; quantify the gains and limits under LN constraints.

- Distinguishing topology-induced vs. transient failures: Extend the framework to include probabilistic channel availability, adversarial HTLC jamming, and liquidity uncertainty; derive reliability bounds that combine geometric feasibility with operational noise.

- Temporal dynamics: Model how and evolve under payment streams and rebalancing; design adaptive policies (routing, fees, opens/closes) that steer the system to remain within feasible regions over time.

- Accessible-wealth scaling validation: Empirically and via simulation, verify scaling, including finite-size effects, variance, and correlation risks introduced by k-party structures; derive confidence intervals for expected accessible wealth.

- Integration with on-chain scaling (channel factories, Ark, batching): Quantify net improvements to and payment throughput after accounting for setup/teardown costs, batching efficiencies, and periodic settlements.

- Privacy implications: Analyze how estimating , coordinating replenishment, and deploying k-party channels impact user privacy; design privacy-preserving variants of the proposed methods.

- Strategic behavior and incentives: Study fee setting, liquidity hoarding, griefing, and DoS in the geometric framework; develop mechanism designs that align incentives with maintaining a large and low .

- Mapping geometry to user metrics: Establish the quantitative link between enlarging (and cut capacities) and improvements in payment success probability, latency, and cost under realistic workloads and constraints.

Glossary

- Asymmetric fees: A fee structure where sending in one direction can cost differently than in the opposite direction; can bias flows and contribute to depletion. "Under linear (asymmetric) fees, cost-minimizing flow within a wealth fiber pushes cycles to the boundary, generically depleting channels except for a residual spanning forest."

- Channel Depletion: The phenomenon where most funds in a channel end up controlled by one peer, reducing routing capacity in the other direction. "Channel Depletion: Most of the liquidity in payment channels is likely to be controlled by one of the two peers maintaining the channel."

- Channel factories: Multiparty channel constructions that allow many users to share a single on-chain funding transaction and open many channels off-chain. "This is used to quantify how multi-party channels (aka coinpools / channel factories) expand "

- Coinpools: Multiparty off-chain arrangements sharing pooled funds to enable many payments/channels with fewer on-chain transactions. "This is used to quantify how multi-party channels (aka coinpools / channel factories) expand "

- Conservation of liquidity: The constraint that in each channel, the sum of both parties’ balances equals the fixed channel capacity. "is called conservation of liquidity."

- Convex/tiered fees: Nonlinear fee schedules that increase with amount or tiers, intended to modulate flow and mitigate depletion. "(ii) convex/tiered fees (local flow control but at odds with source routing without broadcasting realtime liquidity information)"

- Cut capacity: For a partition of nodes, the total capacity of edges crossing the cut; bounds how much wealth can move across that partition. "the total wealth of must lie in an interval whose width equals the cut capacity ."

- Cut interval: The feasible range of total wealth that a subset of nodes can hold, determined by internal edge sums and the cut capacity. "the same as the width of the cut interval of ."

- Dirichlet Rescale Algorithm: A method to uniformly sample integer compositions (wealth distributions) by rescaling Dirichlet samples. "Utilizing the Dirichlet Rescale Algorithm, we can uniformly and randomly select wealth distributions from ."

- DoS attacks: Adversarial strategies to disrupt network operation by flooding or jamming resources. "Barring exploitation of known DoS attacks \cite{harris2020flood,shikhelman2022unjamming,tochner2020route}, the Lightning Network allows users to conduct near real-time Bitcoin payments."

- Embedding: A mapping of an abstract set (e.g., liquidity states) into a coordinate space to study its geometry. "There is a natural embedding:"

- Expected cut width: The expected capacity across a cut under a random topology; used to estimate feasible wealth and payment capacity. "Expected cut width for random topologies in $2$-party channel networks."

- Half-space: A set defined by a linear inequality; used to describe constraints forming polytopes. "intersecting the half-spaces "

- Hyperbox: A Cartesian product of intervals; here, the discrete box representing independent per-channel balances. "isomorphic to an -dimensional hyperbox "

- Hyperedge: An edge connecting more than two vertices in a hypergraph; used to model multiparty channels. "There are potential random hyperedges in total."

- Hypergraph: A generalization of a graph where edges can join any number of vertices; models networks with multiparty channels. "to the cut width of the hypergraph."

- Integer linear programming: Optimization over integer variables with linear constraints/objectives; used to test feasibility of wealth vectors. "This definition motivates the use of integer linear programming to examine because the constraints are linear equations."

- k-uniform hyperedge: A hyperedge that connects exactly k vertices; models a k-party channel. "Modeling a -party channel as a -uniform hyperedge strictly widens every cut in expectation"

- Liquidity function: A function specifying, for each channel and endpoint, the coins owned by that endpoint. "The liquidity function of the network is defined through:"

- Liquidity network: The directed network induced by a liquidity state where each undirected channel is represented by two directed edges with capacities equal to endpoint balances. "we can create the associated liquidity network ."

- Liquidity states : The set of all channel balance assignments consistent with channel capacities. "we define the set of all feasible liquidity functions, or the set of liquidity states of the network, as: "

- Max–flow/min–cut theorem: A fundamental result equating maximum s–t flow to the minimum s–t cut capacity. "By the maxâflow/minâcut theorem \cite{elias1956note,FordFulkerson1956}, "

- Minimum ij-cut: The smallest capacity set of edges whose removal separates i from j; determines payment feasibility. "A payment of amount between users and is feasible if and only if the minimum -cut in is greater than ."

- Monte Carlo methods: Randomized sampling techniques to estimate quantities like feasible-volume ratios. "we can estimate the volume through statistical sampling via Monte Carlo methods."

- Multi-party channels: Channels shared by more than two participants, improving capital efficiency and feasibility. "This is used to quantify how multi-party channels (aka coinpools / channel factories) expand "

- Multi-source, multi-sink flow: A flow with multiple supply and demand nodes; used to test feasibility of wealth vectors. "If a multi-source, multi-sink flow exists that fulfills the supply and demand, then ."

- Off-chain bandwidth: The sustainable rate of payments that can be processed off-chain without on-chain transactions. "the sustainable off-chain bandwidth satisfies"

- On-chain settlement bandwidth: The rate at which on-chain transactions can be confirmed; a bottleneck for resolving infeasible payments. "If is on-chain settlement bandwidth"

- On-chain/off-chain swapping service: A mechanism to exchange off-chain balances for on-chain funds to adjust wealth or topology. "via an on-chain/off-chain swapping service"

- Polytope: A geometric object defined by linear inequalities/equalities; used for both state and wealth feasibility regions. "We introduce a geometric theory of payment channel networks that centers the polytope of feasible wealth distributions"

- Source routing: A routing approach where the sender computes the entire route; may conflict with certain fee designs. "at odds with source routing without broadcasting realtime liquidity information"

- Spanning forest: A collection of trees covering all nodes; here, the residual structure after generic depletion under certain fees. "generically depleting channels except for a residual spanning forest."

- Splicing: Modifying a channel’s capacity/topology by adding/removing on-chain funds without closing the channel. "or through splicing."

- Stars and bars theorem: A combinatorial result counting nonnegative integer solutions to sum constraints; used to count wealth distributions. "the stars and bars theorem"

- State polytopes: Polytopes representing all feasible liquidity states given channel capacities. "Volumes of state polytopes with equally sized channels for various numbers of coins and various numbers of channels."

- Strict circulations: Circulation flows within the network that reassign balances without changing total wealth, used to project states to wealth. "liquidity states naturally projecting onto via strict circulations."

- Throughput law: A relationship linking off-chain payment rate to on-chain capacity and infeasible payment rate. "this yields a simple throughput law linking off-chain scale to feasibility"

- Wealth fiber: The subset of liquidity states corresponding to a fixed wealth distribution; flows within a fiber reassign balances. "cost-minimizing flow within a wealth fiber pushes cycles to the boundary"

- Wealth vector: A vector representation of users’ holdings across the network summing to total coins. "Because of the embedding, we may refer to wealth distributions as wealth vectors."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable applications that leverage the paper’s methods and findings. They are grouped by sector and include dependencies and assumptions that affect feasibility.

- Finance / Payment Infrastructure (Lightning node operators, LSPs, payment processors)

- Capacity planning using the throughput law S = ζ / ρ

- What to do: Measure the expected rate of infeasible payments ρ and translate Bitcoin’s on-chain bandwidth ζ into a sustainable off-chain payment rate S. Use this to set realistic SLAs and plan on-chain budget for channel updates/splices.

- Tools/products: “rho/S dashboard” that continuously estimates ρ from sampled wealth distributions and reports sustainable TPS bands; alerting when ρ rises.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires a reasonable model for ρ (Monte Carlo estimation on W_G), stable topology snapshots, and acceptance of the simplifying model (e.g., measured ρ reflects real payment mix; fees/doS ignored in baseline). ζ reflects effective on-chain throughput available to your operations (not just theoretical maximum).

- Topology and capacity design to enlarge W_G

- What to do: Favor equalized channel capacities (maximizes |L_G|), add edges to relieve bottleneck cuts, and use splicing to reshape capacity rather than opening/closing entirely. For each target market segment, design channel sets that increase cut capacities around expected source–sink pairs.

- Tools/products: “Topology planner” that evaluates candidate channel additions/splices by their marginal effect on r(G) and cut-interval widths; prescriptive suggestions to equalize capacities across existing channels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate network topology view; transaction fees and on-chain budget for splices; willingness to rebalance or rewire channels.

- State-independent feasibility pre-filters for routing

- What to do: Before attempting routes, apply topology-only upper bounds (cut-based capacity bounds) to quickly reject obviously impossible payments (e.g., sender’s max wealth ≤ incident capacity).

- Tools/products: Router modules providing “topological feasibility ceilings” and amount cutoffs per peer pair; reduces futile attempts and probing noise.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Works as a conservative filter (not a guarantee of success), because precise feasibility also depends on unknown wealth state w.

- Depletion mitigation via fee policies and coordination

- What to do: Adopt symmetric per-direction fees for popular corridor channels to reduce directional drift; use convex/tiered fee schedules to discourage large flows on already-depleted paths; orchestrate periodic multi-hop circular rebalances (“coordinated replenishment”) to restore liquidity within the same wealth fiber.

- Tools/products: Fee templates for corridor channels; “depletion early-warning” that detects boundary-pushing cycles; automated circulation selection for cooperative rebalancing among peers/LSPs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Market acceptance of symmetric or convex fee schedules (may reduce short-term fee revenue); coordination mechanisms among nodes; convex/tiered pricing may conflict with source routing and privacy constraints (requires local policy or lightweight liquidity hints).

- Software / Tools (wallets, routers, analytics)

- Feasibility checks and Monte Carlo estimation of r(G) and ρ

- What to do: Implement a “Wealth Polytope Analyzer” that samples feasible wealth vectors (via Dirichlet Rescale sampling) and tests payment updates (w′ = w + a·b_j − a·b_i) for feasibility using max-flow or ILP to estimate ρ for different amounts and payee sets.

- Tools/products: Library/CLI for (i) sampling W(C, n), (ii) feasibility testing on G, (iii) aggregating ρ-by-amount curves, (iv) computing S = ζ/ρ. Integrate into LND/CLN plugins or data platforms.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to (or assumptions about) transaction size distribution; tolerance for computational overhead (batch/offline preferred); fee effects and dynamic liquidity uncertainty may require scenario ensembles rather than single estimates.

- Route selection that accounts for feasible-region geometry

- What to do: Use cut-interval constraints and topology-derived amount ceilings to rank candidate paths; avoid paths that push known bottleneck cuts to the boundary.

- Tools/products: Routing heuristics that incorporate cut widths and predicted depletion risk; fallback strategies (on-chain swap quotes) when predicted ρ is high for a given amount/payee.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Still operates with partial information; relies on topology and statistical priors over wealth vectors rather than exact balances.

- Research / Academia

- Benchmarking frameworks for PCNs

- What to do: Use the W_G framework as a basis for comparing routing strategies, fee policies, and topologies under controlled scenarios; report r(G), ρ-by-amount, and depletion patterns as standard metrics.

- Tools/products: Open-source simulators implementing W_G sampling, feasibility testing, and experiments with fee functions (linear vs convex).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Agreement on benchmark datasets and distributions; reproducibility standards.

- Policy / Regulation

- Communicating capacity constraints of off-chain scaling

- What to do: Use S = ζ / ρ to communicate how on-chain settlement bandwidth and network design jointly cap off-chain throughput; apply this in hearings, risk assessments, and consumer-protection disclosures.

- Tools/products: Policy briefs and stress-test scenarios (e.g., surge increases ρ; resulting S shortfall).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Acceptance that a non-zero ρ is structural for two-party networks; conversion of model metrics into policy-relevant KPIs.

- Daily Life / End Users

- Practical payment limits and expectations

- What to do: Wallets display dynamic “reliable amount ranges” derived from ρ-by-amount curves (e.g., green zone for small payments, amber/red for larger amounts); steer users toward smaller splits or fallback methods when amounts exceed likely feasible regions.

- Tools/products: In-wallet reliability indicators and automatic split-pay features for amounts near cut ceilings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Back-end analytics available from wallet/provider; users accept guidance and occasional split-pay UX.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require protocol evolution, broader ecosystem coordination, or additional research and scaling work.

- Finance / Payment Infrastructure

- Multiparty channels (coinpools/channel factories) at scale

- What to do: Migrate from two-party channels toward k-party channels to expand W_G and increase expected cut capacities—raising sender wealth accessibility ∝ (k/n) and making more payments feasible.

- Tools/products: Production-grade coinpools, channel factories, watchtower integrations; LSP-led “liquidity collectives” pooling capital in multiparty constructs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Protocol support (e.g., covenants such as CTV, SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUT/ANYPREVOUT, or equivalent constructions), robust update/exit safety, privacy-preserving membership changes, UX for multi-party coordination, on-chain fee market considerations.

- Coordinated replenishment protocols

- What to do: Design privacy-preserving, incentive-compatible protocols to select optimal circulations within a wealth fiber and rebalance without excessive on-chain usage.

- Tools/products: Cooperative rebalancing markets and auctions; MPC- or zero-knowledge-assisted coordination (to respect balance privacy).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cryptographic protocols and incentives, new BOLTs or extensions; participant coordination and reputation/trust frameworks.

- Software / Protocols

- Fee mechanism redesign (convex/tiered fee curves)

- What to do: Replace purely linear/asymmetric fees with convex or tiered structures to reduce cycle-pushing to polytope boundaries and alleviate depletion.

- Tools/products: BOLT extensions supporting fee curves; local feedback controllers that change tiers based on congestion/depletion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Routing protocols must ingest richer fee metadata; potential privacy leakage; market acceptance and possible revenue tradeoffs.

- State-aware and privacy-preserving routing

- What to do: Incorporate polytope geometry, cut hints, and privacy-preserving state sharing (e.g., aggregated cut-capacity signals) into next-gen routing.

- Tools/products: Differentially private liquidity broadcasts or “cut-health beacons”; secure multiparty computation to share enough information to improve feasibility without revealing channel balances.

- Assumptions/dependencies: New privacy techniques and industry-standard signals; potential changes to source routing.

- Research / Academia

- Credit/limited-trust extensions to expand W_G

- What to do: Investigate safely bounded credit (temporary negative balances) or collateralized substructures to close infeasibility gaps while retaining trust-minimization where possible.

- Tools/products: Smart-contract designs for pre-funded credit lines with penalties and liquidation; formal analysis of failure modes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: New contract primitives and risk frameworks; community appetite for controlled trust.

- Optimization and control for PCNs

- What to do: Solve for topologies and capacity allocations that maximize r(G) under budget constraints; develop control-theoretic methods to keep the network inside the feasible region with minimal on-chain churn.

- Tools/products: Solvers integrating wealth-polytope constraints; online control policies using observed traffic.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scalable computation and validated demand models; data sharing among operators.

- Policy / Ecosystem

- Standardized reliability metrics and stress testing

- What to do: Adopt ρ and r(G) as standard reliability/scalability metrics across providers; perform coordinated stress tests that vary payment size mix and topology changes.

- Tools/products: Industry reporting standards; regulators and associations maintaining benchmark suites and disclosures.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ecosystem coordination; agreement on measurement and sampling methodologies.

- Cross-Layer / On-chain Interplay

- Increasing effective ζ or offloading topology updates

- What to do: Explore rollups/L3 settlement for channel updates, or on-chain upgrades that reduce the on-chain cost of topology changes (increasing effective ζ), thereby increasing S = ζ / ρ.

- Tools/products: Batchable channel operations (e.g., channel factories, shared UTXO management), rollup-assisted channel management.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Protocol innovations and governance decisions; fee market dynamics; security analyses of new layers.

- Education / Curriculum

- Geometric PCN theory in systems courses

- What to do: Incorporate W_G/L_G, cut-intervals, and S = ζ / ρ into distributed systems and networks curricula to train engineers on capacity limits and design trade-offs.

- Tools/products: Teaching modules and interactive visualizers for wealth polytopes and cut capacities.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Adoption by academic programs and availability of teaching resources.

Notes on Global Assumptions and Model Dependencies

- The core geometric analysis abstracts away from fees, probing, and adversarial dynamics; real deployments must layer these effects back in.

- Many results discuss expected behavior under random topologies or uniform capacity assumptions; operators should validate with their actual demand and topology.

- Exact feasibility decisions require the current wealth vector w, which is generally unknown; practical systems rely on sampling (Monte Carlo) and topology-derived bounds as proxies.

- The benefits of multiparty channels depend on protocol and UX maturity (safety, exit guarantees, privacy). Without these, the theoretical gains in W_G may be hard to realize operationally.

By adopting immediate measurement and planning practices (ρ estimation, topology/capacity design, fee policy guardrails) and progressing toward multiparty channels and coordinated replenishment, the ecosystem can structurally enlarge the feasible region W_G, reduce ρ, and meaningfully improve reliability and throughput.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.