Completed Hyperparameter Transfer across Modules, Width, Depth, Batch and Duration (2512.22382v1)

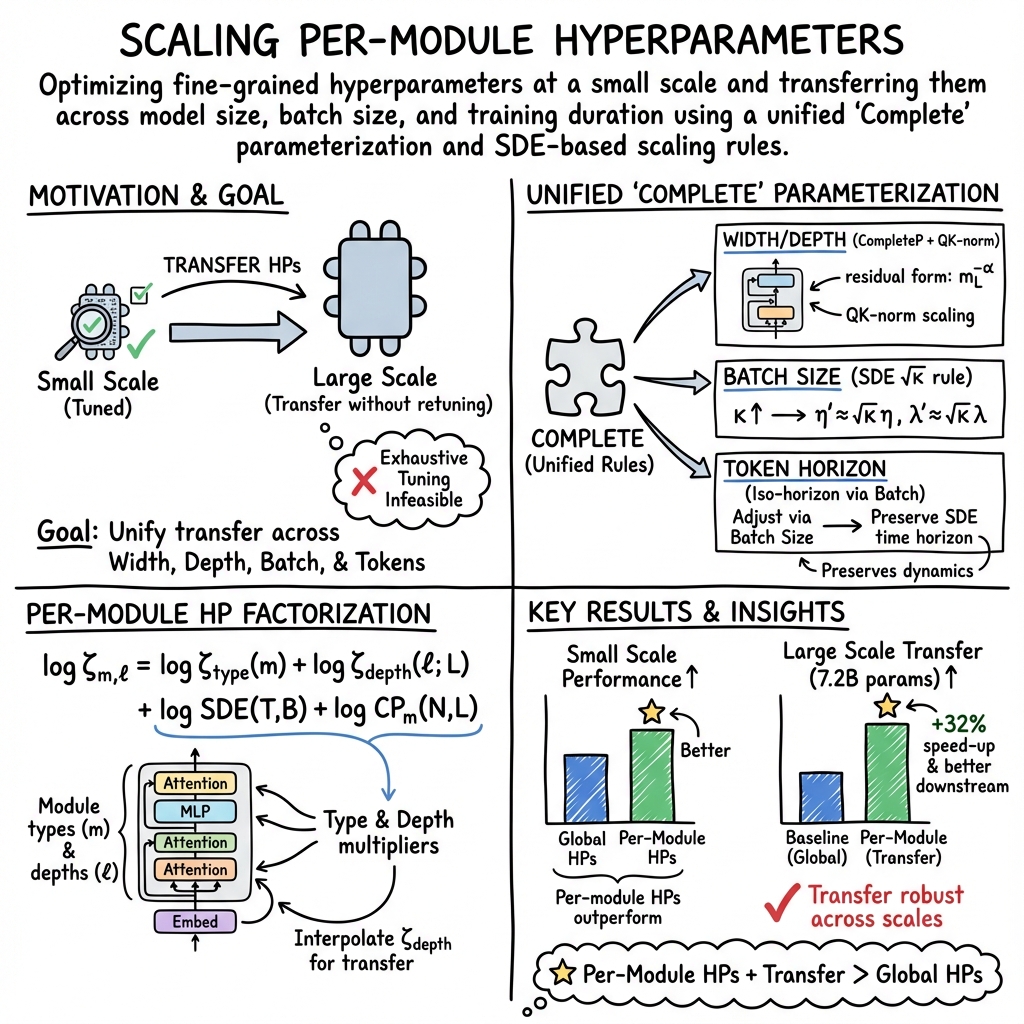

Abstract: Hyperparameter tuning can dramatically impact training stability and final performance of large-scale models. Recent works on neural network parameterisations, such as $μ$P, have enabled transfer of optimal global hyperparameters across model sizes. These works propose an empirical practice of search for optimal global base hyperparameters at a small model size, and transfer to a large size. We extend these works in two key ways. To handle scaling along most important scaling axes, we propose the Complete${(d)}$ Parameterisation that unifies scaling in width and depth -- using an adaptation of CompleteP -- as well as in batch-size and training duration. Secondly, with our parameterisation, we investigate per-module hyperparameter optimisation and transfer. We characterise the empirical challenges of navigating the high-dimensional hyperparameter landscape, and propose practical guidelines for tackling this optimisation problem. We demonstrate that, with the right parameterisation, hyperparameter transfer holds even in the per-module hyperparameter regime. Our study covers an extensive range of optimisation hyperparameters of modern models: learning rates, AdamW parameters, weight decay, initialisation scales, and residual block multipliers. Our experiments demonstrate significant training speed improvements in LLMs with the transferred per-module hyperparameters.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

Training big AI models is a bit like tuning a race car: tiny adjustments can make a huge difference. These tiny adjustments are called hyperparameters (things like how big each training step is, how much to “forget” old information, and how strongly to push weights toward zero). The problem: finding good hyperparameters for a huge model is slow and expensive.

This paper shows how to:

- Find good hyperparameters on a small, cheap model,

- Then reliably reuse (transfer) them when you scale up the model’s width (how wide each layer is), depth (how many layers), batch size (how many examples you process at once), and training duration (how long you train).

They also go further: instead of using one setting for the whole model, they tune hyperparameters per module (different parts like attention, feed-forward layers, embeddings). They show those fine-grained settings can also transfer and speed up training at large scale.

What questions did the researchers ask?

- Can we safely reuse (transfer) hyperparameters found on small models when we scale the model’s width and depth?

- Can we also transfer hyperparameters when we change batch size or how long we train?

- Do “per-module” hyperparameters (different settings for different parts of the network) actually help, and do they transfer too?

- What practical tricks make finding these many hyperparameters easier and more reliable?

How did they study it?

First, a few simple definitions:

- Hyperparameters: the dials you set before training (learning rate, weight decay, AdamW settings, initialization scale, etc.).

- Width: how wide a layer is (number of hidden units).

- Depth: how many layers the model has.

- Batch size: how many examples you process at once.

- Training horizon (or token horizon): how many tokens (words/subwords) you train on in total.

The key idea is parameterization: rules that automatically adjust hyperparameters when you change the model or training setup, so the model behaves “the same” in the right limit. Think of it like scaling a recipe: if you double the people, you don’t always double every ingredient; you adjust smartly so the taste stays balanced.

What they built:

- A unified set of rules they call “Complete” (an improved version of prior work) that tells you how to scale hyperparameters when you change width, depth, batch size, or training duration.

- They adapted these rules to modern Transformer parts, like Query-Key normalization layers.

- They used ideas from continuous-time math (think “smooth curves” instead of “step-by-step”) to figure out how to scale learning rate and weight decay when batch size or training length changes. In simple terms, if you multiply your batch size by k, you should multiply the learning rate by roughly the square root of k, and do the same for weight decay under AdamW. This keeps training “on track” even though you take fewer, bigger steps.

How they looked for good per-module hyperparameters:

- They found that “randomly guessing” settings often fails because training can suddenly become unstable (like falling off a cliff).

- Instead, they used a trust-region local search: start from a good setup and try small, careful tweaks nearby. This works better in landscapes with sharp unstable zones.

- To keep the number of knobs manageable, they factored the tuning into two parts: one per module type (attention, MLP, embeddings, norms) and one per depth (position in the stack), which captures most of the benefit without exploding the number of variables.

They tested everything on decoder-only Transformers trained on the RedPajama dataset, using common modern choices (pre-norm, QK-norm, cosine learning-rate schedule, standard losses).

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Here are the main results, explained simply:

- Hyperparameters transfer across width and depth with the new Complete rules.

- They fixed some technical details (like how to handle QK norms and a small bug in previous formulas) so transfer works more reliably, even for different ways of scaling the residual connections across many layers.

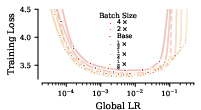

- Batch size changes need square-root scaling.

- If you increase batch size by k, multiply learning rate by about √k. With AdamW, do the same for weight decay. This keeps training behavior consistent when you have more GPUs or memory and want to process more examples at once.

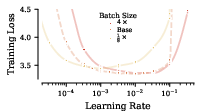

- Training duration changes also need careful scaling.

- If you train for longer (more tokens), the best learning rate gets smaller, roughly like 1/√k (where k is how much longer you train).

- They propose an “iso-horizon” idea: keep the underlying training behavior stable by adjusting settings so you don’t over- or under-shoot when you run longer.

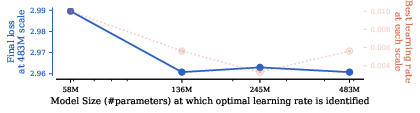

- Per-module hyperparameters help—and they transfer.

- Giving different parts of the model their own learning rates and other settings made training faster and more stable at small scale.

- Crucially, those per-module settings—found on a small model—also worked when transferred to much larger models, giving real speedups. For example, they report around a 1.3× faster time-to-quality and better benchmark scores at large scale.

- Practical tuning advice:

- The hyperparameter landscape has sharp “cliffs”—it’s easy to pick a value that makes training blow up. Random search or naive Bayesian optimization often wastes trials.

- Local, trust-region style search around good points works better.

- Most gains come from giving different module types their own settings; adding simple per-depth multipliers gives extra improvement. A compact factorization (per-module × per-depth) captures nearly all the benefit.

Why this matters: these rules and methods save time and compute. You can find good settings on a small model and be confident they’ll still work after you scale up the model, change batch size, or train longer—making large model training faster, cheaper, and more reliable.

What’s the potential impact?

- Faster and cheaper training of LLMs by reusing small-scale tuning work.

- More stable training when hardware or schedules force you to change batch sizes or training lengths.

- A practical recipe for fine-grained (per-module) tuning that actually carries over to big runs, improving time-to-quality and final performance.

Limitations to keep in mind:

- They tested one training setup (Transformer language modeling with a cosine schedule). The ideas should generalize, but more contexts should be checked.

- Best learning-rate schedules can change shape when you train longer, so you can’t always reuse the exact same schedule—only the scaling rules.

- At extremely large scales, benefits from per-module tuning may shrink, and exact transfer may slowly degrade if the base model you tune is too tiny. Still, the speedups they showed are meaningful in practice.

Overall, this paper provides a clear, unified set of rules and a practical strategy to make hyperparameter tuning portable across model size, batch size, and training duration—plus a way to get extra gains by tuning different parts of the model separately without paying huge re-tuning costs at scale.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single list of concrete gaps, uncertainties, and unexplored questions that remain after this work. Each point is phrased to guide follow-up research.

- Formal guarantees for Complete parameterization: Provide a rigorous proof (beyond empirical checks) that the proposed Complete rules (including QK-norm extensions, embedding/unembedding adjustments, and AdamW-specific choices) yield invariant or near-invariant training dynamics across width and depth for all α in [0.5, 1], and precisely delineate assumptions under which transfer provably holds.

- Full derivation of AdamW SDE scaling: Extend the informal RMSProp-style derivation to full AdamW (including bias corrections, moving-average dynamics, momentum terms, decoupled weight decay, and practical implementations), and prove conditions under which the batch-size square-root scaling and horizon-preserving rules remain valid.

- Transfer breakdown thresholds: Quantify, both theoretically and empirically, the batch-size and step-size regimes where the discrete optimizer stops faithfully approximating the intended SDE (i.e., when “effective step size” is no longer small), and provide diagnostic metrics and safe operating bounds.

- Token-horizon transfer beyond cosine schedules: Validate and refine the iso-horizon rule across diverse learning rate schedules (e.g., warmup-linear, one-cycle, step-decay, exponential), including joint schedule-and-HP scaling; assess whether schedule-dependent scaling laws for all AdamW hyperparameters (not just LR) can be derived.

- Generality across optimizers: Derive and test transfer rules for other widely used optimizers (e.g., Adafactor, Lion, SGD with momentum), including per-module ε, β1/β2 (or equivalent accumulator parameters), and weight-decay scaling under batch-size and horizon changes.

- Gradient clipping interactions: Investigate how gradient clipping thresholds interact with SDE-based transfer (batch-size, horizon) and Complete width/depth scaling, and whether clipping requires its own scaling rules per module.

- Per-module scaling for all HPs: Evaluate transfer and scaling rules for per-module weight decay, β1, β2, and ε across batch-size and token horizon (beyond the global analyses shown), and test whether the same square-root laws and iso-horizon principles hold module-wise.

- Architecture diversity: Test per-module HP transfer and Complete scaling in models with different design choices (post-norm vs pre-norm, RMSNorm vs LayerNorm, tied vs untied embeddings, rotary vs other positional encodings, multi-query attention, MoE, cross-attention) to assess generality and limits.

- QK-norm generalization: Analyze how QK-norm weight sharing interacts with different width-scaling strategies (increasing head dimension vs head count), and derive principled scaling rules for other shared-parameter modules (e.g., shared query/key/value projections, grouped norms).

- Removal of output scalar multiplier: Quantify the impact of reparameterizing away the final logit multiplier on training dynamics, stability, and transfer (especially under Cut Cross-Entropy), and assess whether any hidden coupling is introduced that requires additional scaling adjustments.

- Numerical precision effects: Study whether bf16/fp16/fp8 numerics, kernel fusion, ZeRO optimizer state partitioning, mixed-precision layernorms, and fused AdamW implementations affect transfer validity or require modified scaling.

- Robustness and variance: Increase the number of seeds and report confidence intervals for transfer results (including per-module HPs), to quantify variance and ensure conclusions are statistically robust across random initializations.

- Larger-scale asymptotics: Systematically test per-module HP benefits at much larger scales (e.g., tens/hundreds of billions of parameters and tokens) to determine whether observed diminishing returns are due to non-asymptotic transfer imperfections or represent true asymptotic collapse of per-module advantages.

- Depth-Kronecker factorization limits: Evaluate alternative parameterizations for depth profiles (e.g., low-rank/spline parametrizations, smoothness priors, monotone constraints), compare linear interpolation vs higher-order schemes, and determine whether the Kronecker factorization suffices at greater depths.

- Depth interpolation strategy: Validate whether linear interpolation in depth is optimal; compare against learned or regularized interpolants (e.g., cubic splines, monotone splines) and quantify the impact on transfer at larger depths.

- Stable-region modeling for HPO: Develop models that predict the stability boundary (“cliffs”) in the high-dimensional per-module HP space to enable safe and efficient search (e.g., trust-region BO, non-stationary kernels, adaptive boundary modeling), and benchmark against the proposed trust-region random search.

- Early-stopping proxies: Identify reliable early metrics (e.g., short-horizon losses, gradient statistics) that predict final loss under per-module HP tuning, and integrate them into trial-efficient HPO pipelines.

- Schedule transfer and design: Since the best LR schedules at short horizons are not prefixes of the best long-horizon schedules, devise principled methods to transfer or co-optimize schedules with horizons and batch-size changes (including schedule structure, decay timing, and peak LR scaling).

- Horizon scaling under fixed batch-size: Provide explicit prescriptions for token-horizon scaling when batch-size cannot be changed (e.g., due to hardware constraints), covering how to adjust all AdamW hyperparameters to preserve an SDE horizon while only increasing iterations.

- Distributed training semantics: Clarify how to apply batch-size scaling rules under gradient accumulation and pipeline/tensor parallelism (i.e., what “effective batch size” means for SDE scaling), and validate transfer in realistic distributed setups.

- Data and task transfer: Test whether per-module HPs transfer across datasets (different distributions, multilingual corpora, code), tokenizers, and downstream tasks (including finetuning and RLHF), and determine when retuning is necessary.

- Residual block multipliers: Provide theoretical guidance and empirical sensitivity analyses for residual multipliers (including α choices) under Complete scaling, and study their interactions with per-module HPs and QK-norms.

- Scaling-law integration: Quantify how the proposed token-horizon scaling rules affect compute-optimal training strategies (e.g., Chinchilla-style data/model trade-offs), and report scaling-law exponents and constants under both global and per-module HP regimes.

- Reporting completeness for component fixes: The paper notes epsilon and QK-norm adjustments relative to prior CompleteP; provide exhaustive coordinate checks and ablations to isolate the exact contribution of each fix to transfer robustness, and publish reference implementations validated across architectures.

Glossary

- AdamLH: The original decoupled-weight-decay variant of Adam in which decay is not multiplied by the learning rate. "If one instead uses the original AdamW implementation, often coined AdamLH, as proposed by~\citet{loshchilov2017decoupled},"

- AdamW: An Adam optimizer variant with decoupled weight decay widely used in deep learning. "We extend the parameterisation of \citet{malladi2022sdes}, which yields a consistent SDE limit for Adam, to handle the weight-decay in AdamW."

- Bayesian Optimisation: A surrogate-based global optimization method for expensive functions, often using probabilistic models. "These characteristics make it highly inefficient to use random search and can prove challenging for default Bayesian Optimisation."

- Complete: The paper’s unified parameterisation for transferring hyperparameters across width, depth, batch size, and training horizon. "Crucially, our new parameterisation, {Complete, enables a direct transfer (without any subsequent tuning) to a larger FLOP budget."

- CompleteP: A transformer-specific adaptation of Depth-μP enabling width/depth hyperparameter transfer. "In this work, we build upon CompleteP \citep{dey2025completep},"

- Cut Cross-Entropy: A memory-efficient training technique that avoids materializing the full logits matrix for large vocabularies. "This enables easily incorporating memory-efficient algorithms like Cut Cross-Entropy \citep{wijmans2025cutcross},"

- Depth-μP: An extension of μP that provides rules for transferring hyperparameters across network depth. "This process has been extended to handle changes in depth with Depth-P \citep{yang2024tensor}"

- Depth-ODE limit: The deterministic continuous-depth limit behavior arising under certain residual scaling regimes. "the depth-SDE () or depth-ODE limits () should still exist"

- Evolutionary strategy: A population-based heuristic search method for optimizing hyperparameters. "with an evolutionary strategy."

- Gaussian Process: A nonparametric probabilistic model used as a surrogate in Bayesian optimization. "Commonly, Bayesian Optimisation relies on Gaussian Process (GP) models to guide search."

- Invex: An optimization property where any stationary point is a global optimum. "we observe that, fortuitously, it's pretty close to being invex (stationary points are global minima), and hence might be tractable even despite its high dimensionality."

- Kronecker parameterisation: A factorized representation of per-module hyperparameters into type-wise and depth-wise components. "We adopt a depthâtype Kronecker parameterisation of per-module hyperparameters"

- MuP (μP): The μ-parameterisation enabling hyperparameter transfer across model width without pathological limits. "such as the -parameterisation (P) \citep{yang2022tensorprogramsvtuning}"

- Neural Tangent Parameterisation: A parameterisation leading to the NTK regime, often associated with a lack of feature learning in the infinite-width limit. "Neural Tangent Parameterisation~\citep{jacot2018neural} results in a lack of feature learning~\citep{yang2021featurelearning}."

- Query-Key Normalisation (QK norms): Normalisation applied to the query/key vectors in attention, often sharing weights across heads and requiring special scaling. "we extend the parameterisation to Query-Key (QK) normalisation layers \citep{henry2020querykeynormalizationtransformers},"

- RMSPropW: A variant of RMSProp including weight decay, used as a simplifying example to derive scaling rules. "We consider the same simplifying RMSPropW example as in \citet{malladi2022sdes}."

- Scaling laws: Empirical relationships that predict performance as a function of model size, data, and compute. "Model size and dataset size are two levers to achieve lower loss -- increasing each predictably leads to model improvements, as implied by scaling laws \citep{kaplan2020scalinglawsneurallanguage,hoffmann2022computeoptimal}."

- SDE iso-horizon scaling rule: A rule that scales learning rate with training horizon to keep the SDE integration horizon constant. "The SDE iso-horizon scaling rule empirically permits transfer across training horizon."

- SDE reparameterisation: A parameterisation approach that makes optimizer dynamics approximate an SDE invariant to batch-size changes. "For batch-size scaling, we adapt the SDE reparameterisation in \citep{malladi2022sdes} to AdamW,"

- Standard Parameterisation (SP): A conventional parameterisation that leads to pathological behavior (e.g., exploding features) in the infinite-width limit. "For instance, the Standard Parameterisation (SP) \citep{sohl2020infinite} leads to the features blowing up with size,"

- Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE): A continuous-time stochastic process used to model the limiting dynamics of optimization under noise. "converge to a continuous stochastic process (often described by a Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) \citep{malladi2022sdes})."

- Trust region methods: Optimization techniques that restrict search to local neighborhoods to improve robustness on difficult landscapes. "Many of these difficulties can be alleviated by more robust âtrust regionâ methods"

- Unembedding layer: The final projection from hidden states to vocabulary logits, counterpart to the embedding layer. "each parameter group in the embedding and unembedding layers gets its own value."

- Z-loss: A shift- and scale-invariant loss term used alongside cross-entropy during training. "trained with a mixture of cross-entropy and Z-loss \citep{debrébisson2016zlossshiftscaleinvariant}."

Practical Applications

Overview

This paper introduces a unified parameterization and transfer methodology (“Complete”) that reliably moves hyperparameters (global and per‑module) across the most common scaling axes in modern training pipelines: model width, model depth, batch size, and training duration (token horizon). It demonstrates that tuning per‑module hyperparameters at small scale and transferring them with the right scaling rules yields measurable speed‑ups and improved stability at large scale. The authors also contribute practical guidance for navigating high‑dimensional per‑module hyperparameter optimization (trust‑region local search), and extend SDE‑based scaling rules (including to AdamW weight decay).

Below are the key real‑world applications derived from these findings, grouped into immediate and long‑term opportunities. Each bullet highlights the sector and potential tools/workflows, and notes assumptions or dependencies that affect feasibility.

Immediate Applications

- Adopt “Complete” parameterization to transfer hyperparameters across width, depth, batch size, and token horizon in LLM training pipelines

- Sector: software/AI, MLOps, cloud/HPC

- Tools/workflows: a thin library or config layer that implements Complete scaling (including QK‑norm handling and AdamW

εfixes); “HP transfer calculator” that generates per‑tensor multipliers from base configs; CI checks for transfer invariance across model sizes - Assumptions/dependencies: decoder‑only transformers with pre‑norm, QK norms present; AdamW optimizer; cosine schedule; small‑to‑large behavior approximates the intended infinite‑width/depth limits; batch sizes not so large that the SDE approximation breaks; codebase alignment with PyTorch’s AdamW semantics (vs. AdamLH)

- Use SDE square‑root scaling to adjust learning rate and weight decay when batch size changes, preserving training behavior across different resource configurations

- Sector: MLOps/HPC scheduling, training operations

- Tools/workflows: runtime hooks that rescale

ηandλviaη' = √κ * η,λ' = √κ * λwhen batch size changes by factorκ, and adjust training steps accordingly; dashboards that track “normalized time” - Assumptions/dependencies: gradient noise scales with batch size; same optimizer, same schedule; effective step size remains small; correct handling of AdamW vs. AdamLH scaling differences

- Apply the SDE iso‑horizon rule to scale token horizon by adjusting batch size (rather than peak LR), enabling near‑perfect learning rate transfer and better asymptotic performance

- Sector: AI training, energy/compute efficiency

- Tools/workflows: “horizon policy” that favors batch‑size scaling to extend token counts; a planning tool that co‑optimizes batch size, steps, and LR keeping the SDE time horizon constant

- Assumptions/dependencies: fixed (cosine) schedule; batch size not so large that discretization invalidates SDE limit; same optimizer dynamics over horizon

- Implement per‑module hyperparameter tuning at small scale and transfer the multipliers to large models for speed‑ups and stability gains

- Sector: software/AI model training; startups and academic labs

- Tools/workflows: trust‑region random search for per‑module multipliers (learning rate, weight decay, AdamW

β1,β2,ε, init scales); a registry of module‑wise multipliers; per‑depth Kronecker factorization with linear interpolation for deeper models - Assumptions/dependencies: near‑invex local landscape; careful boundary management to avoid instability “cliffs”; per‑module definitions consistent across scales; Complete scaling rules applied correctly

- Standardize module‑wise HP schemas and config templates to reduce “hyperparameter debt” in large engineering teams

- Sector: MLOps, tooling vendors

- Tools/workflows: typed YAML/JSON schemas for per‑module/per‑depth multipliers; auto‑generation of optimizer parameter groups; linting to enforce embedding/output special cases (e.g., AdamW

εfor embeddings) - Assumptions/dependencies: stable module taxonomy (QKV, attention, MLP, norms, embeddings); consistent naming across codebases

- Combine Complete parameterization with memory‑efficient training techniques (e.g., Cut Cross‑Entropy) by reparameterizing the final projection multiplier into LR/init scale

- Sector: software/AI training, hardware‑constrained environments

- Tools/workflows: a “projection‑free” output layer path; memory audit tools that quantify savings and throughput gains

- Assumptions/dependencies: correctness of reparameterization; compatibility with loss‑layer optimizations

- Improve reproducibility and fairness in benchmarking by publishing “HP Transfer Cards” (base scale configs + transfer multipliers)

- Sector: academia, open‑source communities, policy (research reproducibility)

- Tools/workflows: metadata conventions for per‑module multipliers and scaling rules; repositories of small‑scale HP sweeps that can be used by resource‑constrained labs

- Assumptions/dependencies: community adoption; clarity about optimizer variants and schedules; dataset differences documented

- Reduce training cost and time‑to‑market for industry LLMs by tuning once on a proxy model (e.g., ~50M params, ~1.6B tokens) and transferring per‑module HPs to production scales

- Sector: software/AI product teams, cloud providers

- Tools/workflows: “proxy‑to‑prod” pipelines; speed‑up targets (e.g., the paper reports ~1.32×–1.27× improvements at large scales) embedded into OKRs

- Assumptions/dependencies: proxy faithfully captures dynamics of production architecture; transfer penalties quantified for very small base scales

- Curriculum and lab exercises for graduate ML courses on hyperparameter transfer and SDE‑based scaling

- Sector: education/academia

- Tools/workflows: teaching modules where students tune per‑module HPs at small scale and validate transfer; visualization of “stable/unstable” boundaries; exercises on AdamW vs. AdamLH scaling

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPU availability; curated datasets; alignment with course goals

- Environmental and compute policy reporting: quantify and disclose energy savings from hyperparameter transfer and iso‑horizon scaling choices

- Sector: policy/sustainability, corporate reporting

- Tools/workflows: templates for energy/carbon reporting tied to batch‑size and horizon scaling; internal standards for “transfer‑first” tuning to reduce waste

- Assumptions/dependencies: trustworthy energy metering; acceptance of methodological assumptions by auditors

- End‑user benefit via faster, more stable model updates (shorter retraining cycles, fewer regressions in deployed AI features)

- Sector: consumer software, enterprise platforms

- Tools/workflows: release engineering that integrates transfer‑aware training; rollback strategies less needed due to improved stability

- Assumptions/dependencies: product teams leverage the training gains; monitoring confirms downstream performance alignment

Long‑Term Applications

- AutoML systems for per‑module hyperparameters with trust‑region Bayesian Optimization and early‑stopping, tailored to non‑stationary landscapes

- Sector: AutoML tools, MLOps platforms

- Tools/products: TR‑BO engines specialized for module‑wise HPs; multi‑fidelity schedulers that exploit invex‑like local behavior

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust modeling of fractal‑like stability boundaries; scalable surrogate models; tight integration with training frameworks

- Generalize Complete + SDE scaling rules beyond decoder‑only transformers to encoders, multimodal architectures, diffusion, and non‑Adam optimizers

- Sector: vision, speech, multimodal, scientific ML

- Tools/workflows: adapter libraries that map module taxonomies across architectures; SDE limits for other optimizers (e.g., Adafactor, Lion)

- Assumptions/dependencies: new theory for infinite‑limit behavior in each architecture; empirical validation across tasks and losses

- Joint optimization of schedules and transfer rules (co‑design of LR schedules with horizon scaling), including non‑cosine schedules and learned annealing

- Sector: AI research/engineering

- Tools/workflows: schedule search engines constrained by SDE iso‑horizon; meta‑schedules that evolve with horizon and batch size

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable proxies for long‑horizon behavior; stability guards against greedy schedule artifacts (paper shows best short‑horizon schedule isn’t a prefix of best long‑horizon)

- Adaptive training orchestrators that re‑scale HPs on‑the‑fly as cluster resources, batch sizes, or token budgets change

- Sector: cloud/HPC, MLOps automation

- Tools/workflows: controllers that monitor noise levels and discretization; “resource‑aware” HP adjustment policies; simulators for SDE drift

- Assumptions/dependencies: accurate telemetry (SNR, gradient noise); safe rollout in distributed training; compatibility with mixed precision

- Standards and certifications for “transfer‑ready” training (reproducibility, energy efficiency, optimizer semantics), aiding compliance and procurement

- Sector: policy/regulatory, enterprise IT

- Tools/workflows: checklists for optimizer variants (AdamW vs. AdamLH), schedule disclosure, module taxonomy consistency; third‑party audits

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus in the community; alignment with reproducibility initiatives

- Hardware‑aware scaling (mapping per‑module HP transfer to memory bandwidth, interconnect topology, and accelerator kernels)

- Sector: hardware/software co‑design, accelerators

- Tools/workflows: compilers that emit per‑module optimizer kernels; throughput‑aware rescaling (e.g., overlaps with Cut Cross‑Entropy paths)

- Assumptions/dependencies: mature compiler support; accurate hardware models

- On‑device and edge training: proxy‑scale tuning with transfer to moderately sized on‑device models for personalization

- Sector: mobile/embedded, robotics

- Tools/workflows: lightweight per‑module HP registries; horizon‑aware rescaling given intermittent compute

- Assumptions/dependencies: task/architecture alignment; limited batch sizes may stress SDE assumptions

- New benchmarking protocols that include HP transfer robustness (width, depth, batch size, token horizon) as a first‑class metric

- Sector: academia, benchmarking consortia

- Tools/workflows: multi‑axis transfer suites; reporting lower‑bound coefficients of scaling laws with/without iso‑horizon rules

- Assumptions/dependencies: standardized datasets and evaluation; shared baselines

- Cross‑domain resource equity: enable small labs to reach competitive performance via transfer‑first tuning, narrowing the compute gap

- Sector: academia/policy

- Tools/workflows: public proxies and HP cards; grant programs rewarding transfer‑efficient methods

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain generality proven; curated proxies available

- Theory‑driven exploration of feature diversity and depth scaling (e.g., validating benefits of

α = 1/2in language transformers at larger scales)- Sector: ML theory/research

- Tools/workflows: controlled experiments across α values, with/without QK norms, to study asymptotics and transfer degradation

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to large‑scale compute; robust statistical analyses

Notes on Feasibility and Dependencies (cross‑cutting)

- The method’s strongest evidence is for decoder‑only Transformers trained with AdamW, cosine schedules, and QK norms; care is needed when porting to other architectures/optimizers or schedules.

- SDE‑based transfer rules assume small effective step sizes; very large batch sizes may break the approximation.

- Correct handling of optimizer semantics matters (PyTorch AdamW vs. AdamLH differ in weight‑decay scaling).

- Transfer from too small proxies can incur a penalty; the paper suggests minimal penalty when optimizing at moderately small scales (e.g., ~136M params vs. very small models).

- Per‑module landscapes exhibit sharp instability boundaries; trust‑region methods (or TR‑BO) are more robust than naive random search/standard BO.

- Gains may diminish slowly with scale; continued empirical validation is advised to separate non‑asymptotic effects from true asymptotics.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.