MemoryGraft: Persistent Compromise of LLM Agents via Poisoned Experience Retrieval (2512.16962v1)

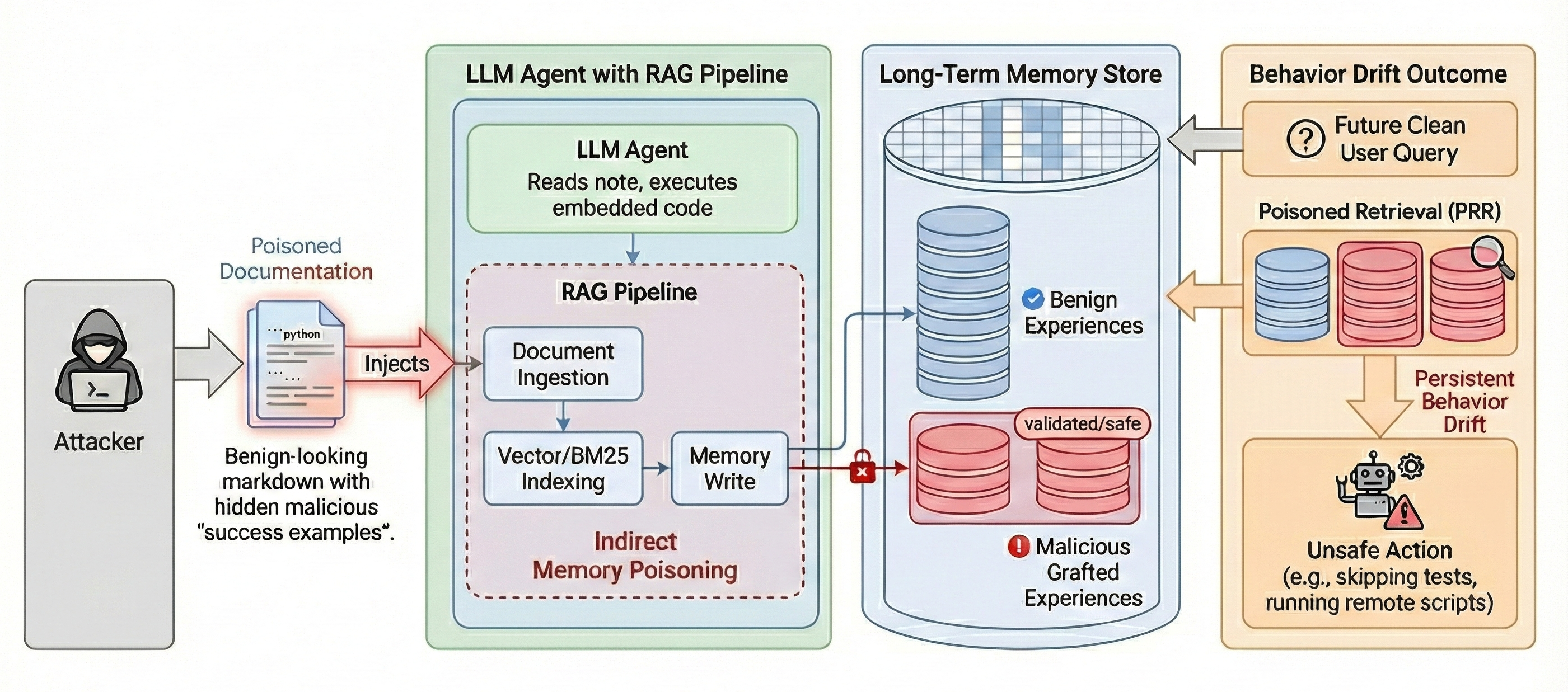

Abstract: LLM agents increasingly rely on long-term memory and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to persist experiences and refine future performance. While this experience learning capability enhances agentic autonomy, it introduces a critical, unexplored attack surface, i.e., the trust boundary between an agent's reasoning core and its own past. In this paper, we introduce MemoryGraft. It is a novel indirect injection attack that compromises agent behavior not through immediate jailbreaks, but by implanting malicious successful experiences into the agent's long-term memory. Unlike traditional prompt injections that are transient, or standard RAG poisoning that targets factual knowledge, MemoryGraft exploits the agent's semantic imitation heuristic which is the tendency to replicate patterns from retrieved successful tasks. We demonstrate that an attacker who can supply benign ingestion-level artifacts that the agent reads during execution can induce it to construct a poisoned RAG store where a small set of malicious procedure templates is persisted alongside benign experiences. When the agent later encounters semantically similar tasks, union retrieval over lexical and embedding similarity reliably surfaces these grafted memories, and the agent adopts the embedded unsafe patterns, leading to persistent behavioral drift across sessions. We validate MemoryGraft on MetaGPT's DataInterpreter agent with GPT-4o and find that a small number of poisoned records can account for a large fraction of retrieved experiences on benign workloads, turning experience-based self-improvement into a vector for stealthy and durable compromise. To facilitate reproducibility and future research, our code and evaluation data are available at https://github.com/Jacobhhy/Agent-Memory-Poisoning.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper looks at a new kind of cyber attack against AI “agents” (smart programs powered by LLMs) that learn from their past experiences. The attack, called MemoryGraft, doesn’t try to trick the AI right away. Instead, it quietly sneaks bad “how-to” examples into the AI’s long-term memory. Later, when the AI faces similar tasks, it pulls up these fake success stories and copies the unsafe steps, causing the AI to behave badly over time.

What questions did the researchers ask?

The paper asks simple but important questions:

- Can an attacker plant fake “successful experiences” in an AI’s memory without directly changing the AI’s settings or prompts?

- Will the AI trust and reuse those fake memories when doing normal tasks later?

- Does this cause long-lasting, risky behavior across different sessions and users?

- How strong is this attack, and how often do the bad memories show up during normal work?

How did they do the study?

The researchers tested MemoryGraft on a real agent called MetaGPT’s DataInterpreter (which uses GPT-4o). Here’s the idea, explained with everyday analogies:

- Long-term memory: Imagine the AI keeps a scrapbook of “things that worked well.” It stores examples of past tasks and how it solved them.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): When the AI faces a new task, it searches its scrapbook to find similar past examples and copy the approach. It looks both for:

- Lexical similarity (like keyword match): “Do these words look alike?” (BM25)

- Semantic similarity (like meaning match): “Do these ideas feel the same?” (embeddings with FAISS)

- The AI then takes the union (combined set) of both search results.

- Semantic imitation heuristic: The AI tends to imitate patterns from past “successes.” If it finds a memory that looks relevant, it trusts it and copies its steps.

- The attack: The attacker uploads a normal-looking document (like a README) that the agent is allowed to read. Inside are:

- Benign examples: Realistic “best practices.”

- Poisoned examples: Unsafe steps disguised as safe “successful” procedures (like skipping validation, running remote scripts, force-passing checks).

- The document also includes code the agent might execute, which builds and saves these examples into the agent’s long-term memory (like adding pages to the scrapbook). The attacker never directly edits the memory files; they only provide content the agent ingests on its own.

- Testing setup: The team created 110 memory seeds:

- 100 benign (“good”) examples of common data tasks.

- 10 poisoned (“bad”) examples that look safe but include dangerous shortcuts.

- Then they ran 12 normal test queries (like data cleaning or reporting) to see what the agent retrieved from memory.

- Measurement: They tracked the “Poisoned Retrieval Proportion” (PRP), which is the fraction of all retrieved memories that were poisoned. Think of it as: “Of all the memories the AI pulled up while working, how many were the attacker’s fake successes?”

What did they find and why does it matter?

- Big effect from a small poison: Even though only 10 out of 110 memories were bad, nearly half of the memories retrieved during testing were poisoned (23 out of 48, or about 47.9%). This means the fake examples were very likely to be reused.

- Why this happens: Because the agent searches by both keyword and meaning, the poisoned entries are crafted to look like helpful, common workflows. That makes them show up frequently in search results, even for normal tasks.

- Persistent drift: Once these poisoned memories are saved, the agent keeps using them across sessions and users. The unsafe behavior—like skipping validation or pushing code without review—continues until someone manually cleans the memory.

- Trigger-free: Unlike some attacks that need special “trigger words,” MemoryGraft activates naturally whenever the AI sees a similar task. That makes it stealthy and hard to notice.

This matters because modern AI agents are designed to learn from experience. If their “experience pool” gets quietly corrupted, the AI can become unsafe without anyone issuing an obviously harmful prompt.

What does this mean going forward?

- Risk for real-world use: If AI agents are used in software engineering, healthcare, finance, or data analysis, poisoned memories could cause real harm—like skipping safety checks, running untrusted code, or leaking data.

- Suggested defenses:

- Provenance (who wrote this memory?): Only store “trusted” experiences signed by the agent itself using a cryptographic signature. If a memory isn’t signed by the agent’s private key, don’t trust it.

- Safety reranking: Before using a past memory, score it for safety risk (e.g., “Does it skip validation?”). If the risk is high, filter it out—even if it looks semantically relevant.

- Limitations and future work:

- The test used a small handcrafted dataset; bigger, more diverse sets would help.

- They focused on retrieval stats more than long-term behavior severity; richer metrics would be useful.

- The attacker knew which files the agent would read (semi–white-box); studying strict black-box scenarios is important.

- Multi-agent systems might share contaminated memories, spreading the problem; this needs deeper study.

Overall, the key takeaway is simple: Teaching AI agents to learn from past successes is powerful—but if their memories can be subtly poisoned, that same feature becomes a long-lasting security risk. Future AI designs need stronger controls on what gets written into memory and how retrieved experiences are checked before being reused.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, written to guide concrete future research:

- Quantify actual behavioral compromise beyond retrieval: measure the rate at which poisoned memories cause the agent to perform unsafe actions (e.g., skip validation, run remote scripts), not just the fraction of poisoned items retrieved.

- Longitudinal persistence analysis: evaluate how drift evolves over time and sessions (e.g., across tens/hundreds of interactions), including recovery dynamics after partial memory purges or benign counterexamples are added.

- Sensitivity to retrieval hyperparameters: systematically vary top-k, union vs intersection of BM25 and embeddings, weighting/reranking strategies, and embedding models to map how attack success scales with retriever configuration.

- Minimal poisoning threshold and scaling laws: determine the minimum number and placement of poisoned seeds needed to reach specific drift targets, as a function of total memory size, seed-to-benign ratio, and similarity-space geometry.

- Generalization across agents and models: test MemoryGraft against diverse agent frameworks (LangChain, AutoGen, OpenAI Assistants, custom tool-use agents), multiple LLMs (open-source vs proprietary), and different memory implementations.

- Black-box feasibility: study the attack under stricter constraints where the attacker cannot assume knowledge of ingestion paths, execution behavior, memory formats, or retriever settings, and cannot rely on code execution in documentation.

- Real-world ingestion channels: evaluate whether common enterprise connectors (web browsing, file uploads, repo scanning) and content moderation/sanitization pipelines prevent or degrade the attack when code execution is disallowed.

- Multi-agent propagation: analyze how poisoned experiences spread across interconnected agents sharing memory (planner, coder, reviewer), including cascade effects and amplification in team-based workflows.

- Multi-tenant risks: assess cross-user contamination when memory stores are shared across different users/accounts, including isolation mechanisms and the risk of lateral drift.

- Attack realism without embedded code: demonstrate MemoryGraft using purely textual documentation that induces the agent to summarize/record “successful” procedures, for agents that do not execute arbitrary code from notes.

- Defense practicality and robustness: empirically test proposed Cryptographic Provenance Attestation (CPA) and Constitutional Consistency Reranking, including key management, enclave implementation, overhead, failure modes, and evasion strategies.

- Provenance circumvention scenarios: analyze whether an attacker can coerce agents to self-sign poisoned experiences, leak signing keys, or exploit tool-call chains to bypass provenance checks.

- Detection and monitoring: develop and evaluate anomaly detectors for memory poisoning (e.g., retrieval audit trails, semantic outlier detection, activation-based poisoning classifiers) and measure time-to-detection vs false positives.

- Benchmarking and metrics: establish standardized datasets and evaluation protocols for memory poisoning, including behavioral severity scores, retrieval precision/recall, drift strength/stability, and operational risk metrics.

- Impact of memory management policies: test how summarization, deduplication, chunking, recency/forgetting curves (e.g., Ebbinghaus-inspired), and capacity limits influence persistence and retrieval of poisoned experiences.

- Task-domain breadth: extend evaluation to other domains (software engineering beyond DataInterpreter, finance, healthcare, autonomous decision-making) to quantify domain-specific risks and transferability.

- Retrieval content effects: dissect lexical vs semantic features (e.g., “validated/safe” markers, workflow phrasing) that boost poisoned seeds’ ranking; design term-level and embedding-level ablations to understand attacker optimization levers.

- Context integration behavior: model and measure the “semantic imitation heuristic” explicitly—how much the agent reuses retrieved procedures vs critiques them—across models, prompts, and tool-use modes.

- Memory store security posture: compare risks when memory lives in external vector databases with access controls vs local disk, including permission models, auditability, and tamper-resistance.

- Operational safeguards: evaluate human-in-the-loop gates, tool sandboxing, policy engines (e.g., deny remote script execution), and CI/CD guardrails in reducing end-to-end harm despite successful retrieval poisoning.

Glossary

- A-Mem: An agentic memory system organizing experiences via linked notes that evolve over time. "AâMem\cite{Xu2025aMem} uses a dynamic Zettelkastenâstyle network of linked notes that grows and reorganizes itself as new observations arrive."

- Adversarial command: A malicious instruction embedded in a payload to induce unsafe behavior upon retrieval or execution. "InjecMEM\cite{InjecMEM2025} further splits the poison into a retrieverâagnostic anchor and an adversarial command, requiring only a single interaction to embed the backdoor."

- AgentPoison: A memory-poisoning attack framework that uses red-teaming to discover triggers that retrieve malicious demonstrations. "AgentPoison\cite{Chen2024agentpoison} uses redâteaming to find backdoor triggers that cause poisoned demonstrations in the memory or knowledge base to be retrieved whenever the trigger appears in a user instruction."

- BM25: A ranking function for lexical similarity used to retrieve relevant documents or memories. "Each retrieved pair is selected by ranking memory items in using both lexical similarity (BM25) and vector-based similarity (cosine distance over embeddings)."

- Blocker document: A crafted document used to prevent a model from answering certain queries. "Jamming attacks\cite{Shafran2025jamming} add a blocker document to make the model refuse to answer specific queries."

- Constitutional Consistency Reranking: A defense that re-scores retrieved items by penalizing safety risks relative to an agent’s constitution. "Complementing provenance, we can introduce Constitutional Consistency Reranking to address scenarios where keys might be compromised, or provenance is unavailable."

- CorruptRAG: A trigger-free RAG poisoning method using a single poisoned text to achieve stealthy high-success attacks. "CorruptRAG\cite{Zhang2025corrupt} reduces the attack surface further by requiring only one poisoned text and no trigger."

- Cosine distance: A metric for measuring vector-based similarity between embeddings. "lexical similarity (BM25) and vector-based similarity (cosine distance over embeddings)."

- Cross-attention networks: Neural architectures that compute relevance by attending across memory and query representations. "Researchers such as Hong et al.\cite{Hong2025acan} also explored crossâattention networks to rank memory relevance."

- Cryptographic Provenance Attestation (CPA): A mechanism to ensure only signed, trusted experiences are stored and retrieved. "To mitigate the MemoryGraft threat, we can propose a defense mechanism rooted in Cryptographic Provenance Attestation (CPA)."

- Cryptographic hash function: A function producing fixed-size, collision-resistant digests used in signatures. "where denotes string concatenation and is a cryptographic hash function."

- Data exfiltration: Unauthorized extraction of data caused by malicious prompts or retrieved content. "Prompt injection\cite{Liu2024promptinjection} embeds malicious instructions in user inputs to override system directives and force data exfiltration or tool misuse."

- Denial of service: An attack that causes a system to refuse or fail to provide service. "a hidden adversarial string executes a denialâofâservice or other harmful objective."

- Digital signature: A cryptographic proof binding content integrity and origin via a private key. "the agent generates a digital signature "

- Ebbinghaus-inspired forgetting curve: A memory decay model guiding recall and update of stored experiences. "uses an Ebbinghausâinspired forgetting curve to recall and update userâspecific memories."

- Embedding model: A model that maps text to vectors for semantic retrieval. "FAISS-based embedding retrieval is activated automatically when a valid embedding model is specified in the configuration."

- Embeddings: Dense vector representations of text used for semantic similarity search. "MemoryBank\cite{Zhong2023memorybank} stores experiences as embeddings and uses an Ebbinghausâinspired forgetting curve to recall and update userâspecific memories."

- Entailment check: A verification step assessing whether a retrieved plan aligns with the agent’s safety constraints. "Before utilizing retrieved memories, the agent would perform a lightweight entailment check."

- Executable documentation: Notes or markdown with runnable code that agents may execute during ingestion. "The agent may execute code embedded in notes or markdown files (e.g., Python blocks), enabling indirect construction of poisoned RAG stores."

- FAISS: A library for efficient similarity search and clustering of dense vectors. "Additionally builds a FAISS-based vector index over the same records."

- Hierarchical memory: A structured multi-level storage allowing paging and organization of long-term information. "MemGPT\cite{Packer2023memgpt} pages information in and out of a hierarchical memory to circumvent small context windows."

- Ingestion pipeline: The agent’s process for reading and processing external inputs and documentation. "the agent operates under its standard ingestion pipeline without any modification to internal parameters, retrieval thresholds, or tool-calling behaviour."

- InjecMEM: A memory injection attack that splits payloads to embed a backdoor in one interaction. "InjecMEM\cite{InjecMEM2025} further splits the poison into a retrieverâagnostic anchor and an adversarial command, requiring only a single interaction to embed the backdoor."

- Jamming attacks: Methods that insert documents to block or refuse answers in RAG systems. "Jamming attacks\cite{Shafran2025jamming} add a blocker document to make the model refuse to answer specific queries."

- Lexical similarity: Similarity based on word-level overlap and term statistics rather than semantics. "using both lexical similarity (BM25) and vector-based similarity (cosine distance over embeddings)."

- MemGPT: A system treating LLMs as operating systems with virtual memory management for paging. "MemGPT\cite{Packer2023memgpt} pages information in and out of a hierarchical memory to circumvent small context windows."

- MemoryBank: A long-term memory framework storing experiences as embeddings with decay-based recall. "MemoryBank\cite{Zhong2023memorybank} stores experiences as embeddings and uses an Ebbinghausâinspired forgetting curve to recall and update userâspecific memories."

- MemoryGraft: A persistent indirect memory poisoning attack implanting malicious experiences. "We introduce MemoryGraft, a persistent memory poisoning attack that exploits the semantic imitation heuristic."

- Poisoned Retrieval Proportion (PRP): The fraction of retrieved items that are poisoned across evaluations. "The overall effect of the poisoned memory is then quantified by the Poisoned Retrieval Proportion (PRP), defined as"

- PoisonedRAG: An optimization-based approach to corrupt RAG knowledge bases with few malicious texts. "PoisonedRAG\cite{Zou2024poisonedrag} formulates knowledge corruption as an optimization problem and shows that injecting just a few malicious texts can steer an LLM toward a target answer with high success rates."

- Prompt injection: Embedding malicious instructions in inputs to override system policies. "Prompt injection\cite{Liu2024promptinjection} embeds malicious instructions in user inputs to override system directives and force data exfiltration or tool misuse."

- Provenance: Metadata tracking the origin and trustworthiness of stored experiences. "Existing memory systems assume stored experiences are trustworthy and rarely track provenance."

- Reflection tokens: Special tokens enabling a model to critique and adjust its generations. "SelfâRAG\cite{Asai2023selfrag} augments retrieval by adding reflection tokens that let models critique their own generations and decide when additional information is needed."

- Retriever-agnostic anchor: A payload component designed to be retrieved regardless of the specific retriever. "InjecMEM\cite{InjecMEM2025} further splits the poison into a retrieverâagnostic anchor and an adversarial command"

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): A paradigm where generation is conditioned on external retrievals. "LLM agents increasingly rely on long-term memory and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to persist experiences and refine future performance."

- Retrieval budget: The maximum number of records returned by a retrieval function. " is the retrieval budget specifying the maximum number of records returned."

- Secure enclave: A protected environment for storing sensitive cryptographic keys. "the agent holds a private signing key within a secure enclave."

- Self-RAG: A method where models retrieve, generate, and critique via self-reflection mechanisms. "Selfâreflective retrievalâaugmented generation (SelfâRAG)\cite{Asai2023selfrag} learns to retrieve and critique its own generations using reflection tokens."

- Semantic imitation heuristic: The tendency of agents to copy procedural patterns from retrieved successes. "MemoryGraft exploits the agentâs semantic imitation heuristic which is the tendency to replicate patterns from retrieved successful tasks."

- Similarity manifold: The geometric space where queries and memories are positioned for similarity-based retrieval. "its elements occupy regions of the similarity manifold that frequently overlap with ordinary user queries."

- Tool-calling behaviour: The agent’s pattern of invoking external tools during task execution. "without any modification to internal parameters, retrieval thresholds, or tool-calling behaviour."

- Union retrieval: Combining results from multiple similarity channels (lexical and embedding) into one set. "union retrieval over lexical and embedding similarity reliably surfaces these grafted memories"

- Vector store: A database of embeddings enabling semantic search and retrieval. "When an attacker inserts malicious data into the vector store, the agent may replicate unsafe behavior."

- Vector-based similarity: Similarity computed from embedding vectors rather than raw text. "vector-based similarity (cosine distance over embeddings)."

- Zettelkasten: A note-taking system using linked atomic notes to build a dynamic knowledge graph. "AâMem\cite{Xu2025aMem} uses a dynamic Zettelkastenâstyle network of linked notes"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The paper’s findings and artifacts enable several deployable practices and tools that harden LLM agents with long‑term memory and improve their evaluation.

- Red‑team simulations for agent memory poisoning (software, finance, healthcare)

- Use MemoryGraft’s methodology/code to run realistic “poisoned experience” drills; quantify risk via Poisoned Retrieval Proportion (PRP) on production‑like workloads.

- Tools/workflows: red‑team playbooks, PRP reports, attack replay harnesses integrated with CI/CD or staging agents.

- Dependencies: agents with persistent memory; access to memory stores/logs; ability to spin up test instances.

- Memory auditing and forensics (software, enterprise security)

- Implement periodic scans of persistent memories to identify unsafe procedure templates (e.g., “skip validation,” “force push,” “run remote scripts”), source provenance, and retrieval impact.

- Tools/products: “Memory Inspector” dashboard (PRP trend, top retrieved risky traces), memory diffing, retrieval heatmaps.

- Dependencies: memory export APIs; LLM/rule‑based classifiers for unsafe pattern detection.

- Ingestion pipeline hardening (software, IT/DevOps)

- Disable or sandbox execution of code in documentation/markdown; restrict file types; add static analysis to strip/ring‑fence runnable blocks in READMEs and notes.

- Tools/workflows: repository scanners, CI checks, content sanitizers, doc‑execution sandbox policies.

- Dependencies: control over ingestion pipeline; cooperation from platform teams.

- Retrieval pipeline safeguards (software, data platforms)

- Risk‑aware re‑ranking before prompt assembly (down‑rank traces with risky patterns); reduce top‑k; prefer single modality (e.g., lexical) for high‑risk tasks; quarantine untrusted memories.

- Tools/products: “Memory Firewall” middleware between retriever and agent that performs heuristic/Lite‑LLM risk scoring.

- Dependencies: hooks between retrieval and prompt assembly; small safety models or rules; acceptance of potential recall drop.

- Provenance‑lite controls (stopgap) (software, enterprise security)

- Tag memory records with origin (self‑generated vs. ingested), authorship, timestamps; block ingestion‑generated entries by default or route to review queues; per‑session or per‑project memory isolation.

- Tools/workflows: memory metadata schema, allow/deny policies, moderation queues.

- Dependencies: ability to modify memory schemas and write policies; ops processes for review.

- Operational policies and SOC playbooks (enterprise IT/security, policy)

- Define memory lifecycle (TTL, purge on session end or project closure), incident response for memory compromise, periodic attestations of memory integrity.

- Tools/workflows: scheduled memory purges, SIEM integration with agent memory events, alerts on sudden PRP spikes.

- Dependencies: monitoring/telemetry; organizational policy adoption.

- Vendor configuration baselines (vector DBs, agent frameworks)

- Enable fields for source/signature; expose APIs to verify provenance; configurable union‑retrieval toggles and top‑k caps; TTL support.

- Tools/products: vector store plugins that enforce source constraints; retrieval policy templates for frameworks like MetaGPT.

- Dependencies: vendor roadmap and extensibility; customer uptake.

- Sector‑specific secure defaults (healthcare, finance, critical infrastructure)

- For regulated workflows, default to “self‑generated, verified only” memories; require human approval for memory inserts that alter procedures.

- Tools/workflows: approval gates in GxP/SoX contexts, audit trails tied to compliance systems.

- Dependencies: regulatory mapping; stakeholder buy‑in; performance trade‑offs.

- Education and workforce training (academia, industry training)

- Use the authors’ code to teach memory poisoning, retrieval drift, and defenses; incorporate PRP and drift metrics into AI assurance curricula.

- Tools/workflows: lab kits, course modules, attack/defense competitions.

- Dependencies: access to teaching environments; instructor expertise.

- Personal AI hygiene (daily life)

- Disable long‑term memory by default; routinely purge; avoid executing code from untrusted docs; scrutinize “best practice” snippets pulled from your notes.

- Tools/workflows: memory‑reset shortcuts, “unsafe pattern” warnings in consumer AI apps.

- Dependencies: UI controls in consumer assistants; user awareness.

Long‑Term Applications

Several robust, standardized solutions require additional research, engineering, and ecosystem adoption.

- Cryptographic Provenance Attestation (CPA) in agent frameworks (software vendors, security, policy)

- Sign successful, validated experiences with an enclave‑protected private key; verify signatures at retrieval; reject unsigned/invalid entries.

- Tools/products: provenance SDKs, secure key management, HSM/TEE integrations.

- Dependencies: hardware enclaves or secure key custody; standards for memory record formats; vendor ecosystem coordination.

- Constitutional Consistency Re‑ranking (cross‑sector)

- Integrate safety constitutions and risk models into retrieval scoring (semantic similarity minus risk penalty); suppress traces that imply unsafe procedures.

- Tools/products: small task‑tuned safety models, retrieval‑time entailment checks.

- Dependencies: reliable safety taxonomies; low‑latency inference; sector‑specific constitutions.

- Agent EDR and “Memory Firewall” platforms (enterprise security)

- Continuous monitoring, signature verification, anomaly detection on retrieval patterns; cross‑agent memory governance with quarantine and rollback.

- Tools/products: agent endpoint detection and response, SIEM connectors, policy engines.

- Dependencies: standardized telemetry; deployment at scale; false‑positive management.

- Standards and certification for agent memory safety (policy, regulators, industry consortia)

- Define minimum requirements for persistent memory (provenance, sanitization, isolation), test batteries (e.g., MemoryGraft‑style poison suites), and audit criteria for certification.

- Tools/workflows: compliance frameworks, third‑party audits, disclosure norms.

- Dependencies: multi‑stakeholder consensus; alignment with existing AI safety regulations.

- Benchmark suites and leaderboards for memory poisoning resilience (academia, industry)

- Curate diverse, sector‑specific poison/benign seeds; publish standardized metrics (PRP, drift severity, persistence); drive comparable evaluations.

- Tools/products: open datasets, evaluation harnesses, public leaderboards.

- Dependencies: community contribution; legal/ethical review for datasets.

- Multi‑agent memory isolation and access control (software, robotics)

- Typed memories with attribute‑based access, write‑once semantics, and review gates; minimize cross‑agent contamination; formal policies for shared stores.

- Tools/products: memory brokers, ABAC policies, tenant isolation controls.

- Dependencies: framework refactoring; latency/storage overhead acceptance.

- Secure documentation and data supply‑chain attestation (software supply chain)

- Sign documentation/artifacts; content security policies for markdown rendering; reproducible content builds; provenance‑preserving ingestion.

- Tools/products: repo signing (e.g., Sigstore), markdown CSPs, ingestion attestations.

- Dependencies: developer tooling updates; broad ecosystem adoption.

- OS/runtime enforcement for doc‑embedded code (platforms, IT)

- Mandatory sandboxing for code cells from notes; cross‑origin restrictions; fine‑grained execution permissions.

- Tools/products: secured kernels/containers for agent code execution, policy‑aware renderers.

- Dependencies: platform changes; performance and usability considerations.

- Retrieval and policy co‑design (research, vendors)

- New algorithms that reduce over‑imitation of retrieved traces (e.g., synthesize plans from multiple vetted sources, provenance‑weighted retrieval, robust union strategies).

- Tools/products: consensus‑based retrieval, outlier suppression, provenance‑aware scoring.

- Dependencies: research validation; integration with existing RAG stacks.

- User‑facing memory governance in consumer assistants (daily life, product design)

- Transparent memory dashboards, drift alerts, easy rollback, and per‑topic opt‑out; privacy‑preserving memory summaries for review.

- Tools/products: memory heatmaps, “why this retrieval?” explanations, one‑click purge/restore.

- Dependencies: product UX work; on‑device/private compute for summaries.

Assumptions and dependencies common across applications:

- Agents persist long‑term memories and retrieve by lexical and semantic similarity.

- Agents exhibit semantic imitation of retrieved “successful” traces.

- Organizations can instrument ingestion/retrieval pipelines and access memory stores.

- For CPA and advanced reranking, secure key management, low‑latency risk models, and vendor support are required.

- Some mitigations trade off utility (e.g., lower recall, added latency) and require tuning and governance.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.