Bolmo: Byteifying the Next Generation of Language Models

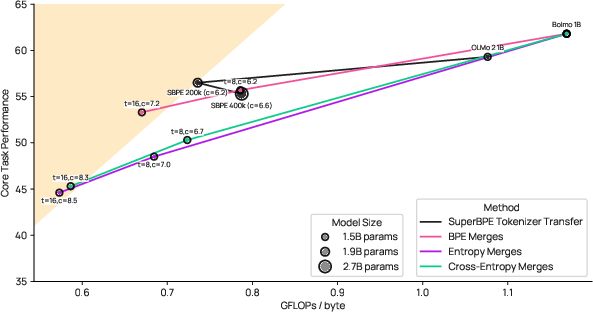

Abstract: We introduce Bolmo, the first family of competitive fully open byte-level LMs at the 1B and 7B parameter scales. In contrast to prior research on byte-level LMs, which focuses predominantly on training from scratch, we train Bolmo by byteifying existing subword-level LMs. Byteification enables overcoming the limitations of subword tokenization - such as insufficient character understanding and efficiency constraints due to the fixed subword vocabulary - while performing at the level of leading subword-level LMs. Bolmo is specifically designed for byteification: our architecture resolves a mismatch between the expressivity of prior byte-level architectures and subword-level LMs, which makes it possible to employ an effective exact distillation objective between Bolmo and the source subword model. This allows for converting a subword-level LM to a byte-level LM by investing less than 1\% of a typical pretraining token budget. Bolmo substantially outperforms all prior byte-level LMs of comparable size, and outperforms the source subword-level LMs on character understanding and, in some cases, coding, while coming close to matching the original LMs' performance on other tasks. Furthermore, we show that Bolmo can achieve inference speeds competitive with subword-level LMs by training with higher token compression ratios, and can be cheaply and effectively post-trained by leveraging the existing ecosystem around the source subword-level LM. Our results finally make byte-level LMs a practical choice competitive with subword-level LMs across a wide set of use cases.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

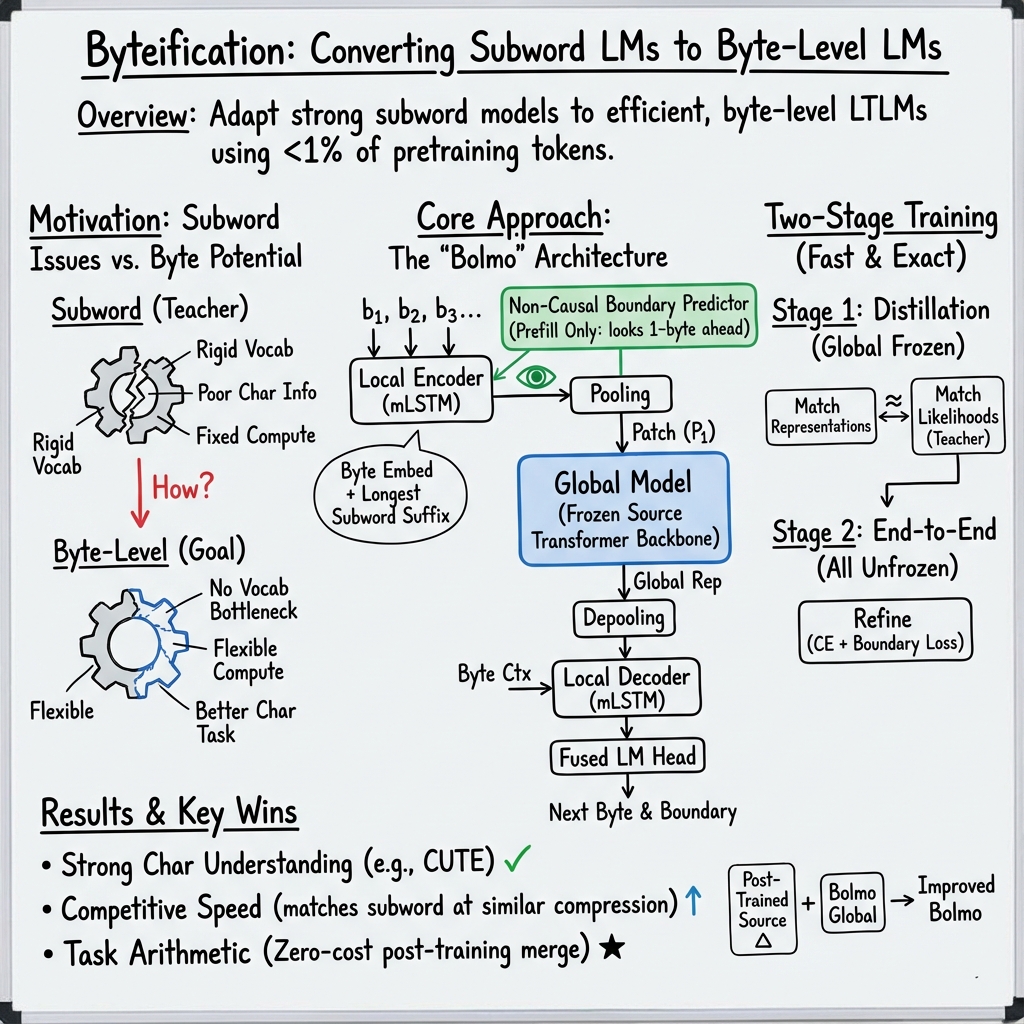

This paper introduces Bolmo, a new kind of LLM that reads text at the byte level (tiny units like the ones computers use to store letters and symbols). Instead of building a brand-new byte model from scratch, the authors “byteify” an already strong subword model (a model that reads bigger chunks like parts of words) and turn it into a byte model with very little extra training. Their goal is to make byte-based models practical, fast, and competitive with today’s best subword-based models across many tasks.

What problem is the paper trying to solve?

Modern LLMs split text into “subword tokens” (pieces like “un-”, “believ-”, “able”). That approach has several downsides:

- They don’t understand characters (letters, accents, punctuation) as well as they could.

- Tokenization can be biased: how words are split sometimes “leaks” hints about the future text in weird ways.

- A fixed subword vocabulary doesn’t cover all languages perfectly.

- Computation (how much “brain power” the model spends) is tied to those tokens, which isn’t always efficient.

Byte-level models can fix many of these issues because they work with the smallest units (bytes), but until now they were hard to train to the same quality as the best subword models. The paper asks: Can we convert a strong subword model into a byte-level model quickly and make it just as good (or better on some tasks)?

How does Bolmo work? (Methods explained simply)

Think of Bolmo as a two-team system reading text:

- A “local team” that scans raw bytes quickly (like a fast reader who looks letter by letter).

- A “global team” (the original transformer from the subword model) that thinks deeply about chunks of text (like a careful reader who reasons about larger meaning).

Bolmo follows a design called a Latent Tokenizer LLM (LTLM). Here’s the flow in everyday terms:

- Bytes come in (every character is stored as one or more bytes).

- The local encoder (a lightweight neural network called mLSTM) turns each byte into a small representation.

- A boundary predictor decides where to cut the byte stream into “patches” (short chunks). Importantly, Bolmo’s boundary predictor peeks one byte into the future. This peek matches how subword tokenizers decide word boundaries (they also use future context). That makes Bolmo’s chunking just as “expressive” as subword tokenization.

- The model pools bytes in each patch into a single patch representation (like summarizing a short chunk).

- The global model (the original big transformer from the subword model) processes the sequence of patch summaries.

- Then the model “de-pools” the patch outputs back to bytes.

- The local decoder (another mLSTM stack) turns them into final predictions: the next byte and whether a boundary happens right after it.

A few helpful analogies and clarifications:

- “Bytes” are the basic computer units for characters; there are 256 possible byte values.

- “Patches” are short chunks of consecutive bytes the model treats as higher-level units.

- The boundary predictor is like a smart cutter that decides where one chunk ends and the next starts. Bolmo lets it peek one character ahead during the initial reading phase, which makes cutting more natural (like noticing “flower” vs “flowers” before cutting).

- Predicting boundaries during generation: Bolmo also teaches the decoder to output a special symbol (think of it as

"<b>"), meaning “a boundary happens here,” right alongside the next byte. To keep things fast, it “fuses” boundaries with bytes (so the decoder chooses between 512 options: each of the 256 bytes, with or without a boundary).

Two-stage training (“teach then refine”)

Instead of training everything from scratch, Bolmo uses two stages:

- Stage 1: Distillation (teacher–student learning)

- The strong subword model is the teacher. Bolmo (the byte model) is the student.

- The student learns to mimic the teacher exactly:

- It learns where the teacher would put boundaries.

- It learns to turn bytes into patch representations that match what the teacher expects (so the teacher’s transformer can be reused).

- It learns to produce the same likelihoods (confidence in the next token/byte) as the teacher, patch by patch.

- This is very efficient: the global model stays frozen, so training is much faster.

- Stage 2: End-to-end training

- Now the whole Bolmo model is trained together.

- The model learns to fully exploit byte-level information.

- It can also increase “compression” (more bytes per patch), which makes inference faster because the global model processes fewer steps.

Overall, this two-stage process lets Bolmo reuse the powerful parts of existing subword models while carefully swapping in byte-based components.

What did they find?

In experiments, Bolmo performed very well:

- It beat previous byte-level models of similar size by a large margin.

- Compared to the original subword models, Bolmo was better at tasks that need fine-grained character understanding (like exact letters, accents, punctuation) and sometimes better at coding tasks.

- On most other tasks, Bolmo came close to matching the source subword models.

- It can run at competitive speeds with subword models, especially when trained to use higher compression (more bytes per patch = fewer steps for the global model).

- It can be post-trained cheaply by reusing the training ecosystem around the original subword model (saving time and compute).

This matters because it shows byte-level models can be practical and strong, not just an interesting idea.

Why is this important?

- Better character-level understanding: Helps with tasks like handling unusual spellings, many languages, code, and exact text operations.

- Fairer across languages: Byte-level processing doesn’t rely on a fixed subword vocabulary, which can miss or inefficiently encode words outside major languages.

- Efficiency and speed: By adjusting how many bytes go into each patch, the model can trade off detail for speed when appropriate.

- Easy conversion path: Instead of needing massive training runs from scratch, you can “byteify” a good subword model in a fraction of the usual cost (less than 1% of typical pretraining tokens).

- Opens research doors: With public models, data, and code, others can build byte-level models more easily, test new ideas, and make language technology more robust and inclusive.

Final takeaway

Bolmo shows a practical, fast way to turn strong subword LLMs into byte-level models that keep up on most tasks and excel on character-sensitive ones. By teaching the new byte model to mimic the old model first (distillation) and then training it end-to-end, Bolmo brings the benefits of byte-level processing—better character understanding, fewer tokenization quirks, and flexible efficiency—into the next generation of LLMs.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper. Each point is phrased to be actionable for future research.

- Quantify tokenization-bias mitigation: Does Bolmo’s learned, non-causal latent tokenization (and especially the retained subword-suffix embeddings) still encode subword-induced tokenization biases during prefill or decoding? Provide targeted benchmarks and diagnostics for bias leakage and prompt-sensitivity at word/whitespace boundaries.

- Multilingual efficiency and coverage: UTF-8 byte granularity can be inefficient for non-Latin scripts (e.g., CJK). Evaluate speed–quality trade-offs across diverse scripts, and test alternatives (e.g., Unicode code points, learned byte-group units) for multilingual efficiency without losing the byte-level benefits.

- Larger or adaptive lookahead for boundaries: The boundary predictor uses only one byte of future context during prefill. Explore larger, learned, or adaptive lookahead windows (including unrestricted lookahead) and quantify their impact on accuracy, latency, and semantic boundary coherence.

- Differentiable non-causal boundary learning without leakage: End-to-end boundary training with lookahead risks leaking future information. Develop training mechanisms (e.g., privacy-preserving constraints, information bottlenecks, noise or regularization schemes, or causal masking variants) that enable differentiable non-causal boundary learning safely.

- Prefill–decode boundary consistency: Measure and reduce mismatch between boundaries chosen in prefill (via non-causal predictor) and those implicitly emitted during decoding (<b> symbol). Provide statistics on boundary agreement rates and the effects on generation quality, streaming, and long prompts.

- Boundary thresholding and adaptivity: The impact of the decision threshold for boundary placement (speed–quality Pareto) is not analyzed. Study threshold calibration, adaptive thresholding by domain/context, and user-controllable compression policies.

- Generalization beyond teacher’s subword boundaries: Stage 1 strongly supervises boundaries to match subword tokenization. Investigate relaxing or annealing boundary supervision to allow Bolmo to depart from subword boundaries where beneficial, and quantify downstream gains or risks.

- Distillation sensitivity and stability: The “exact” subword-to-byte distillation uses temperature-modulated BCE over patch likelihoods. Analyze sensitivity to temperature, length, and numerical stability; report failure modes (e.g., long tokens, rare tokens, or extreme entropy cases) and propose robust variants.

- Impact of retained subword-suffix embeddings: Retaining subword embedding tables (via longest-suffix addition) may reintroduce subword-specific biases and complexity. Ablate their contribution to performance, efficiency, and tokenization bias; explore alternatives (larger local encoder capacity, MoE, or learned sparse embeddings) that avoid subword artifacts.

- Overhead and calibration from boundary-symbol fusion: Doubling the output vocabulary to fuse boundary symbols (<b>) could affect calibration, rare-byte modeling, and long-tail Unicode. Measure its effect on perplexity, calibration (ECE), and error patterns; compare against explicit boundary tokens.

- Local module design space: The choice of mLSTM stacks is justified by speed, but alternatives (e.g., CNNs, gated MLPs, state-space models, MoE local layers) are not systematically explored. Benchmark accuracy/latency/memory trade-offs across local encoder/decoder families.

- Depooling strategy limitations: Depooling by linear projection plus last-patch addition may bottleneck fine-grained byte reconstruction. Compare against attention-based depooling, learned interpolation, or multi-head depooling to improve byte-level fidelity.

- Scaling laws for byteification: Characterize how Stage 1 and Stage 2 token budgets, n-layer matching depth, and model size impact final quality. Provide scaling curves to guide minimal-cost byteification at different sizes (e.g., 1B, 7B, >30B).

- Applicability to closed-weight teachers: Stage 1 requires intermediate hidden states from the teacher (M_:n). Develop black-box byteification methods that rely only on logits (or distillable features available via API) to extend to closed models.

- Knowledge-intensive and coding regressions: The paper notes mixed outcomes (e.g., DS-1000) versus the teacher. Diagnose where knowledge/coding performance lags (error taxonomy, context-length sensitivity, boundary density around identifiers) and propose targeted data or architectural remedies.

- Long-context behavior and memory footprint: Analyze KV-cache size and memory vs. compression ratio during long-context prefill/decoding. Provide latency breakdowns (local vs. global modules) and stress tests at extreme context lengths.

- Inference-speed transparency across hardware: Report standardized, end-to-end latency and throughput comparisons (tokens/sec or bytes/sec) on common accelerators and batch sizes, including prefill vs. decode phases and varying compression ratios.

- Training-time efficiency and energy: Provide training FLOPs/energy for Stage 1 and Stage 2, and compare to training from scratch and to subword continued pretraining, to substantiate the “<1% budget” claim across scales.

- Robustness to noisy/edge Unicode: Evaluate robustness on malformed UTF-8, combining marks, ZWJ/ZWNBSP, and complex grapheme clusters. Measure boundary stability and accuracy around multi-byte code points and grapheme boundaries.

- Safety, bias, and toxicity: No safety/bias evaluations are reported. Assess whether byteification changes toxicity, demographic bias, jailbreaking susceptibility, or safety alignment relative to the teacher.

- Post-training transferability limits: “Zero-cost post-training” is claimed, but the scope (e.g., supervised finetuning, instruction tuning, RLHF, safety tuning) and fidelity are not quantified. Benchmark how well post-trained behaviors transfer and where gaps emerge.

- Generalization across architectures: Bolmo assumes equal local/global dimensionality and reuses the teacher’s global model. Study byteification for models with mismatched dims, encoder–decoder architectures, MoE backbones, or rotary/positional variants that complicate stitching.

- Compression-policy learning: Explore learning a policy that dynamically trades off compression (bytes/patch) vs. performance per input segment or task, possibly via reinforcement learning or auxiliary rewards.

- Evaluation breadth on tokenization-specific phenomena: Beyond CUTE/EXECUTE, include comprehensive tests for token-boundary sensitivity (whitespace truncation, mid-word prompts), byte-level homographs/homoglyphs, and adversarial spacing/Unicode attacks.

- Uncertainty calibration and generation quality: Assess how byteification affects calibration, entropy, repetition, and degeneracy, including effects of boundary density on sampling dynamics.

- Open-source reproducibility details: Provide precise implementation costs of suffix-embedding lookup, boundary inference pipelines, and their runtime overheads to enable faithful reproduction and fair comparisons.

- Cross-modal or multi-token prediction extensions: Investigate whether Bolmo’s latent tokenization interacts beneficially with multi-token prediction or other acceleration techniques, and whether gains are additive or redundant.

- Theoretical understanding of latent tokenization: Develop formal analyses of why one-byte lookahead suffices empirically, and what properties of byte distributions and subword boundary rules explain the empirical success or failure modes.

Glossary

- autoregressive models: Models that generate the next token by conditioning on previous tokens in a sequence. Example: "has been pioneered for autoregressive models by the Hourglass Transformer"

- binary cross-entropy: A loss function for binary classification that measures the difference between predicted probabilities and actual binary labels. Example: "via a binary cross-entropy loss"

- byteification: The process of converting a subword-tokenized LLM into a byte-level model. Example: "we train Bolmo by byteifying existing subword-level LMs."

- causal LLMs: LLMs that only use past context (no future information) to predict the next token. Example: "as in causal LLMs"

- compute allocation: How computational resources are distributed across tokens or parts of a model during processing. Example: "potentially suboptimal compute allocation"

- compression ratio: The number of original units (e.g., bytes) represented by a single compressed unit (e.g., a patch) in the model. Example: "by training with higher compression ratios of bytes per patch"

- cross-attention pooling: A pooling mechanism where representations attend to inputs via cross-attention to produce aggregated vectors. Example: "which also encompasses the cross-attention pooling done by \citet{pagnoni-etal-2025-byte}."

- cross-tokenizer distillation: Knowledge distillation where a teacher and student use different tokenizers, transferring behavior across tokenization schemes. Example: "effective tokenizer transfer methods based on cross-tokenizer distillation have been introduced"

- depooling: The operation of expanding patch-level (pooled) representations back to byte- or token-level representations. Example: "This is similar to \citet{hwang2025dynamicchunkingendtoendhierarchical}'s depooling"

- dynamic tokenization: Tokenization that adapts boundaries based on content or learned criteria, instead of fixed rules. Example: "replacing static pooling with dynamic tokenization improves the performance--efficiency Pareto front"

- exact distillation: A distillation objective that aims to exactly match the teacher model’s behavior (e.g., probabilities) at fine granularity. Example: "an effective exact distillation objective between Bolmo and the source subword model."

- FLOPs: Floating point operations; a measure of computational cost used to compare training or inference efficiency. Example: "when spending the same total amount of FLOPs on training"

- hash embeddings: Embeddings computed via hash functions to increase capacity with sparse parameters. Example: "Inspired by BLT's hash embeddings"

- Hourglass Transformer: An architecture that pools local tokens into fewer global tokens for efficient long-context modeling and then upsamples back. Example: "has been pioneered for autoregressive models by the Hourglass Transformer"

- KV cache: The stored key and value tensors from attention layers used to speed up autoregressive decoding. Example: "every token contributes equally to the KV cache size"

- KV cache sparsification: Techniques that reduce KV cache memory/computation by sparsifying stored states. Example: "such as KV cache sparsification"

- Latent Tokenizer LLMs (LTLMs): Byte-level models that learn internal tokenization into patches within the network. Example: "which we refer to collectively as Latent Tokenizer LLMs (LTLMs)"

- lookahead: Using future context (e.g., upcoming bytes) when making a boundary or tokenization decision. Example: "larger (or unrestricted) lookaheads"

- mLSTM: A modern linear-time LSTM variant used for efficient local sequence modeling. Example: "The local encoder contextualizes the byte-level embeddings through an mLSTM layer"

- mixture of experts: A modular architecture where multiple expert networks are selectively activated for inputs to increase capacity efficiently. Example: "using a mixture of experts in the feed-forward layer"

- model stitching: Analyzing or training by connecting parts (layers) of different models to compare or transfer representations. Example: "inspired by research on model stitching"

- multi-token prediction: Methods that predict multiple future tokens at once to improve efficiency or accuracy. Example: "and multi-token prediction"

- non-causal boundary prediction: Predicting token/patch boundaries using future context, unlike causal schemes restricted to past context. Example: "We describe non-causal boundary prediction in detail in Section~\ref{sec:non_causal_boundaries}"

- output boundary prediction: Emitting explicit boundary symbols as part of the model’s output to mark patch ends during decoding. Example: "predicting the boundary symbol <b> is analogous to the output boundary prediction in \citet{fleshman2023toucantokenawarecharacterlevel}"

- Pareto frontier: The set of models where improving one metric (e.g., efficiency) would worsen another (e.g., performance). Example: "efficiency--performance Pareto frontier"

- prefill: The phase where the model consumes the initial prompt/context before starting autoregressive generation. Example: "Subword-level LMs non-causally set boundaries over the prefill using the external subword tokenizer"

- retrofitting: Modifying an existing model’s architecture or tokenizer with additional training to add capabilities. Example: "Techniques to alter a model's architecture with extra training are typically referred to as retrofitting"

- straight-through estimator: A technique to backpropagate gradients through discrete decisions by using a surrogate gradient. Example: "and (ii) a straight-through estimator of the boundary scores"

- subword tokenization: Segmenting text into units smaller than words (subwords) from a fixed vocabulary for model input. Example: "subword tokenization causes a number of problems."

- temperature-modulated binary cross-entropy: A binary cross-entropy adjusted by a temperature parameter to soften or sharpen targets. Example: "we choose the temperature-modulated binary cross-entropy"

- tokenization bias: Leakage of information about future content via the chosen tokenization, which can affect model behavior. Example: "Tokenization bias is the phenomenon that sequences of tokens can implicitly leak information about the future content of the text they tokenize."

- tokenizer transfer: Techniques for changing a model’s tokenizer (e.g., subword to byte) while preserving behavior via distillation. Example: "Recently, effective tokenizer transfer methods"

- transducer: A model that transforms an input sequence into a longer or shorter output sequence, not one-to-one aligned. Example: "turned from an isotropic model to a transducer from "

- UTF-8 bytes: The 256 possible byte values used to represent text in UTF-8, serving as atomic units for byte-level LMs. Example: "switching to UTF-8 bytes."

- upprojection: A learned linear mapping to increase dimensionality of representations before passing to a higher-capacity module. Example: "obviating the need for an upprojection."

- vocabulary bottleneck: Limitations caused by a fixed subword vocabulary that cannot cover all linguistic variation efficiently. Example: "the vocabulary bottleneck;"

Practical Applications

Overview

Below are practical applications derived from the paper’s findings and innovations around byte-level LLMs (Bolmo), byteification of subword LMs, non-causal boundary prediction, and dynamic latent tokenization. Each item names specific use cases, links to sectors, suggests tools/workflows, and notes assumptions or dependencies that influence feasibility.

Immediate Applications

These are deployable now with the released models, code, and dataset.

- Robust multilingual and noisy-text processing for customer-facing systems

- Use Bolmo-7B/1B in chatbots, content moderation, translation pre/post-processing, and data ingestion where text contains names, mixed scripts, OCR artifacts, emojis, and rare Unicode (e.g., healthcare EHR, legal filings, financial identifiers, e-commerce forms).

- Sectors: healthcare, government, finance, e-commerce, education.

- Potential tools/workflows: switch to byte-level tokenization in existing pipelines; integrate bolmo-core; adopt “bytes-per-patch” compression tuning for long inputs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: minor accuracy trade-offs on some tasks vs. subword LMs; ensure inference stack supports mLSTM local modules and boundary prediction; review domain-specific evaluation (CUTE/EXECUTE for character understanding).

- Safer, more predictable generation in safety-critical prompts

- Mitigate tokenization bias (e.g., mid-word endings, trailing whitespace) in assistants and agents to avoid unintended completions or leaked information about future text segments.

- Sectors: software, safety engineering, public services.

- Potential tools/workflows: replace subword tokenizers with Bolmo; use non-causal boundary prediction during prefill; add boundary symbol fusion for efficient decoding.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: overall safety still requires broader guardrails; prompt-level evaluations must confirm reduced bias for target use cases.

- Faster long-context inference via compression tuning

- Reduce inference cost for retrieval-augmented generation, summarization, and analytics by increasing “bytes per patch,” maintaining competitive speeds with subword LMs.

- Sectors: legal, research, enterprise IT, cloud/energy.

- Potential tools/workflows: deploy compression policies (threshold scheduling, entropy-based boundary thresholds); profile KV-cache savings; integrate with RAG systems.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: speed–accuracy trade-off must be tuned per workload; hardware kernels for mLSTM and depooling should be optimized.

- Code assistants with improved handling of whitespace and non-standard tokens

- Use Bolmo in IDEs for auto-completion and refactoring where non-English comments, unusual identifiers, and formatting matter; leverage improved coding performance “in some cases.”

- Sectors: software, DevTools.

- Potential tools/workflows: integrate Bolmo-7B into VSCode plugins; adopt boundary-aware completions; evaluate on HumanEval/MBPP/DS benchmarks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: coding gains vary by task; ensure licensing and model card compliance; measure latency with compression settings.

- Zero-cost post-training reuse to accelerate domain adaptation

- Reuse existing post-trained checkpoints (e.g., task-specific Olmo fine-tunes) to post-train the byteified model without additional cost.

- Sectors: enterprise ML, applied research.

- Potential tools/workflows: map source LM adapters/checkpoints onto Bolmo; implement cross-check validation; automate Stage 1/Stage 2 orchestration.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: architectural compatibility with source LM; adapter translation may need tooling; validate parity on domain metrics.

- Tokenization-free data engineering

- Simplify ETL by avoiding language-specific tokenizers; reduce failures due to rare characters or mixed encodings in ingestion and preprocessing.

- Sectors: data engineering, analytics.

- Potential tools/workflows: unify text normalization around UTF-8 bytes; standardize boundary prediction thresholds; expose patch boundaries for downstream segmentation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: downstream tasks must accept byte-level inputs or patch boundaries; performance benchmarking on representative corpora is recommended.

- Research and teaching on character-level phenomena

- Use Bolmo to study orthography, morphology, and character-level reasoning with improved accuracy (CUTE/EXECUTE); explore latent tokenization as a segmentation signal.

- Sectors: academia (NLP, linguistics), education.

- Potential tools/workflows: replicate/extend CUTE/EXECUTE experiments; analyze patch boundaries as learned segmentation; run distillation baselines with <1% pretraining tokens.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: results depend on dataset composition (Bolmo Mix, Dolma 3); keep evaluation reproducible across languages and scripts.

- On-device assistants using Bolmo-1B

- Deploy the 1B model for multilingual command understanding on robots and edge devices, benefiting from dynamic compute allocation and smaller footprint than many subword LMs.

- Sectors: robotics, IoT.

- Potential tools/workflows: quantization; kernel optimization for mLSTM; compression tuning per device constraints.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: hardware support for efficient RNN/Transformer kernels; evaluate latency vs. accuracy on-device.

- Policy and compliance audits for tokenization bias

- Assess and reduce tokenization-related harms in public-sector or regulated deployments by adopting byte-level models where tokenization bias could lead to unpredictable outcomes.

- Sectors: public policy, compliance, governance.

- Potential tools/workflows: add tokenization-bias checks to model validation; document boundary behaviors; set guidance on prompt formatting and mid-word endings.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: institutional willingness to change standards; need to maintain transparency via documentation and bias reports.

Long-Term Applications

These need further research, tooling, scaling, or ecosystem support before broad deployment.

- Byteify-any-model frameworks and “Byteify-as-a-Service”

- Generalize the two-stage byteification (exact distillation, end-to-end fine-tuning) to diverse subword LMs (e.g., Llama/Mistral families), enabling rapid porting with <1% token budgets.

- Sectors: ML platform providers, cloud ML.

- Potential tools/workflows: automated cross-tokenizer distillation pipelines; adapter translation between subword and byte-level; CI/CD for byteification.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: access to source weights and training artifacts; attention to licensing; robust tooling for boundary alignment and representation matching.

- Standardization: byte-level tokenization as a default

- Evolve industry and public-sector guidelines to favor byte-level tokenization in multilingual, safety-critical, and long-context applications.

- Sectors: policy, compliance, standards bodies.

- Potential tools/workflows: evaluation protocols for tokenization bias; official benchmarks (CUTE/EXECUTE variants); governance checklists.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: broad community acceptance; reproducible evidence of parity or improvements vs. subword baselines across domains.

- Adaptive compute scheduling via latent tokenization

- Systematically allocate compute where needed, varying patch sizes dynamically to improve efficiency and throughput while maintaining accuracy.

- Sectors: energy/cloud optimization, large-scale inference.

- Potential tools/workflows: compression schedulers; entropy-based boundary controllers; multi-tenant inference policies.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: careful monitoring of trade-offs; kernel and compiler support; task-specific calibration to avoid degradation.

- Larger or learned lookahead for boundary prediction

- Increase lookahead beyond one byte during prefill to improve semantic coherence in patching (e.g., compounds, multi-byte characters) without leaking future content at decode.

- Sectors: translation, text analytics, search.

- Potential tools/workflows: non-causal boundary modules with controlled information flow; formal analyses to prevent leakage pathways.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: training stability; mitigation for degenerate solutions; framework support for prefill-only non-causality.

- Universal fine-tune/adapter translation (subword ↔ byte-level)

- Build robust tools to translate LoRA/adapters/checkpoints across tokenization regimes for quick domain adaptation of byteified models.

- Sectors: enterprise ML, DevOps for ML.

- Potential tools/workflows: adapter mapping libraries; validation harness; automated alignment metrics.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: architecture compatibility; representation equivalence beyond embedding layers; community-driven tooling.

- Low-resource language expansion

- Leverage byte-level tokenization to scale support for under-represented languages without building per-language vocabularies.

- Sectors: public services, education, localization.

- Potential tools/workflows: targeted Stage 2 training with local corpora; evaluation with multilingual character understanding benchmarks; community datasets.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: data availability and quality; domain adaptation strategies; careful validation for fairness and robustness.

- Retrieval, indexing, and segmentation using learned boundaries

- Use latent tokenization boundaries for document segmentation, morphological analysis, and search indexing to improve retrieval quality across scripts.

- Sectors: search, knowledge management.

- Potential tools/workflows: patch-aware indexers; hybrid char/patch embeddings; pipeline integration for document stores.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: empirical gains vs. conventional tokenizers; tooling support for boundary-aware retrieval; benchmark creation.

- Binary-level generation and firmware patching

- Extend byte-level modeling to generate, analyze, or patch binary/firmware safely (assembly, hex, base64), benefiting from exact byte modeling.

- Sectors: cybersecurity, embedded systems.

- Potential tools/workflows: specialized datasets; safety constraints; binary-aware evaluation metrics.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: stringent safety/testing; domain data curation; risk management for production use.

- Privacy-preserving generation and reduced meta-leakage

- Investigate whether eliminating tokenization bias measurably reduces leakage patterns and improves privacy in sensitive deployments.

- Sectors: privacy tech, regulated industries.

- Potential tools/workflows: formal audits; privacy benchmarks; red-team evaluations focused on prompt edge cases.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: rigorous empirical evidence; complementary privacy controls; legal and compliance alignment.

- Multi-modal hierarchies with shared latent tokenization concepts

- Transfer LTLM ideas (local encoders, global models, dynamic pooling) to audio/image/video, creating unified hierarchical models.

- Sectors: media, robotics, AR/VR.

- Potential tools/workflows: cross-modal boundary prediction; patch-level fusion; hardware-aware scheduling.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: architecture generalization to other modalities; training scale; domain-specific benchmarks and datasets.

Notes on Tools, Products, and Workflows

- Open resources: Bolmo-7B and Bolmo-1B (Hugging Face), Bolmo Mix dataset, bolmo-core codebase.

- Deployment knobs: bytes-per-patch compression; boundary thresholds; non-causal boundary predictor for prefill; fused

<b>symbol for decoding efficiency. - Byteification pipeline: Stage 1 exact distillation of subword LM behaviors (with limited backprop through first n transformer layers), Stage 2 end-to-end training to exploit byte-level signals and adjust compression.

- Ecosystem reuse: Ability to leverage existing post-trained checkpoints from source subword LMs for byteified models, reducing adaptation cost.

These applications rely on careful tuning of compression ratios and boundary prediction strategies, validation on target tasks, and hardware/software support for mLSTM and depooling kernels to fully realize the efficiency and robustness benefits described in the paper.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.