ACE-SLAM: Scene Coordinate Regression for Neural Implicit Real-Time SLAM (2512.14032v1)

Abstract: We present a novel neural RGB-D Simultaneous Localization And Mapping (SLAM) system that learns an implicit map of the scene in real time. For the first time, we explore the use of Scene Coordinate Regression (SCR) as the core implicit map representation in a neural SLAM pipeline, a paradigm that trains a lightweight network to directly map 2D image features to 3D global coordinates. SCR networks provide efficient, low-memory 3D map representations, enable extremely fast relocalization, and inherently preserve privacy, making them particularly suitable for neural implicit SLAM. Our system is the first one to achieve strict real-time in neural implicit RGB-D SLAM by relying on a SCR-based representation. We introduce a novel SCR architecture specifically tailored for this purpose and detail the critical design choices required to integrate SCR into a live SLAM pipeline. The resulting framework is simple yet flexible, seamlessly supporting both sparse and dense features, and operates reliably in dynamic environments without special adaptation. We evaluate our approach on established synthetic and real-world benchmarks, demonstrating competitive performance against the state of the art. Project Page: https://github.com/ialzugaray/ace-slam

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces ACE-SLAM, a new way for a camera to figure out where it is and build a 3D map of its surroundings at the same time, all in real time. This task is called SLAM, short for Simultaneous Localization and Mapping. ACE-SLAM uses a small neural network as its map, which makes it fast, memory‑efficient, and good at quickly “re-finding” where the camera is after it moves or gets confused.

What questions did the authors ask?

- Can we build a SLAM system that runs at camera speed (real time) using a compact neural map?

- Can we avoid slow, graphics-like “ray casting” methods and still get accurate camera tracking and useful 3D geometry?

- Can the system quickly relocalize (re-find its position) and handle moving objects without special add‑ons?

- What’s the best way to design the neural network map so it learns fast during live use?

How does their system work?

Think of ACE-SLAM like a smart “world GPS” for a camera:

- It takes an RGB-D video (color images + depth) as input.

- It finds “interesting spots” in each image (features), like corners or textured patches.

- It learns a compact “address book” that maps those image spots to their real 3D positions in the world.

Here’s the flow, in simple steps:

- Input and features: For each frame, the system detects a set of 2D features and reads their depth. This turns them into 3D points in the camera’s local view.

- The learned map (Scene Coordinate Regression, SCR): A small neural network takes each feature’s appearance and directly predicts where that feature is in the global 3D world. Imagine recognizing a storefront and instantly knowing its street address.

- Finding the camera’s position (relocalization): Once the network predicts the world positions of many features in a frame, the system computes the best camera pose that aligns those predicted world points with the frame’s local 3D points. It tries multiple quick guesses and picks the one that fits most points (like trying many puzzle piece placements and keeping the best).

- Training the map on the fly: While tracking, the system keeps training the neural map using frames that were harder to align. This helps it rapidly improve and adapt to new areas.

- Keyframes and smart sampling: It chooses some frames as “keyframes” to keep the map accurate and balanced over time, focusing compute on frames or areas that need more help.

- Always-on relocalization: Because it constantly re-fits the camera to the map, it can naturally close loops (when returning to a place seen before) and recover from brief failures or motion.

- Keeping it real-time: The system limits how many frames and points it processes per cycle so it stays at or near the camera’s frame rate. If needed, it can skip frames to keep up.

A new network design: TriMLP (triplane coordinate voting)

Most systems predict 3D coordinates with a small “fully connected” network. The authors propose TriMLP, which predicts 3D positions by “voting” on three 2D grids: top view (XY), side view (XZ), and front view (YZ). Each view suggests where the point could be, and then the system averages these to get the final 3D position.

Simple analogy: To find a point in a room, you ask three friends—one looking from above, one from the side, and one from the front. Each gives their best guess on a 2D map. Combine their guesses, and you get the 3D location. This structure helps the network learn faster and adapt during live mapping.

What did they find?

In tests on standard datasets (Replica, TUM-RGBD, and ScanNet), ACE-SLAM showed:

- Real-time speed: It runs at around the camera’s frame rate on consumer hardware, achieving close to 100% real-time factor in their tests—much faster than many neural SLAM methods that need much more time than a live video feed.

- Small maps: The whole learned map can be about 1 MB—far smaller than many alternatives—so it’s memory friendly.

- Competitive accuracy: While not always the most accurate in every case, it is on par with older methods and approaches newer ones on many sequences, especially impressive given its real-time operation and simplicity.

- Fast relocalization: Because the network directly predicts world coordinates for image features, the system can quickly re-find its position without slow rendering steps.

- Robustness to moving objects: Without special modules like semantic segmentation, it still tracks well in scenes with people or objects moving. The relocalization step naturally ignores points that don’t fit the static world.

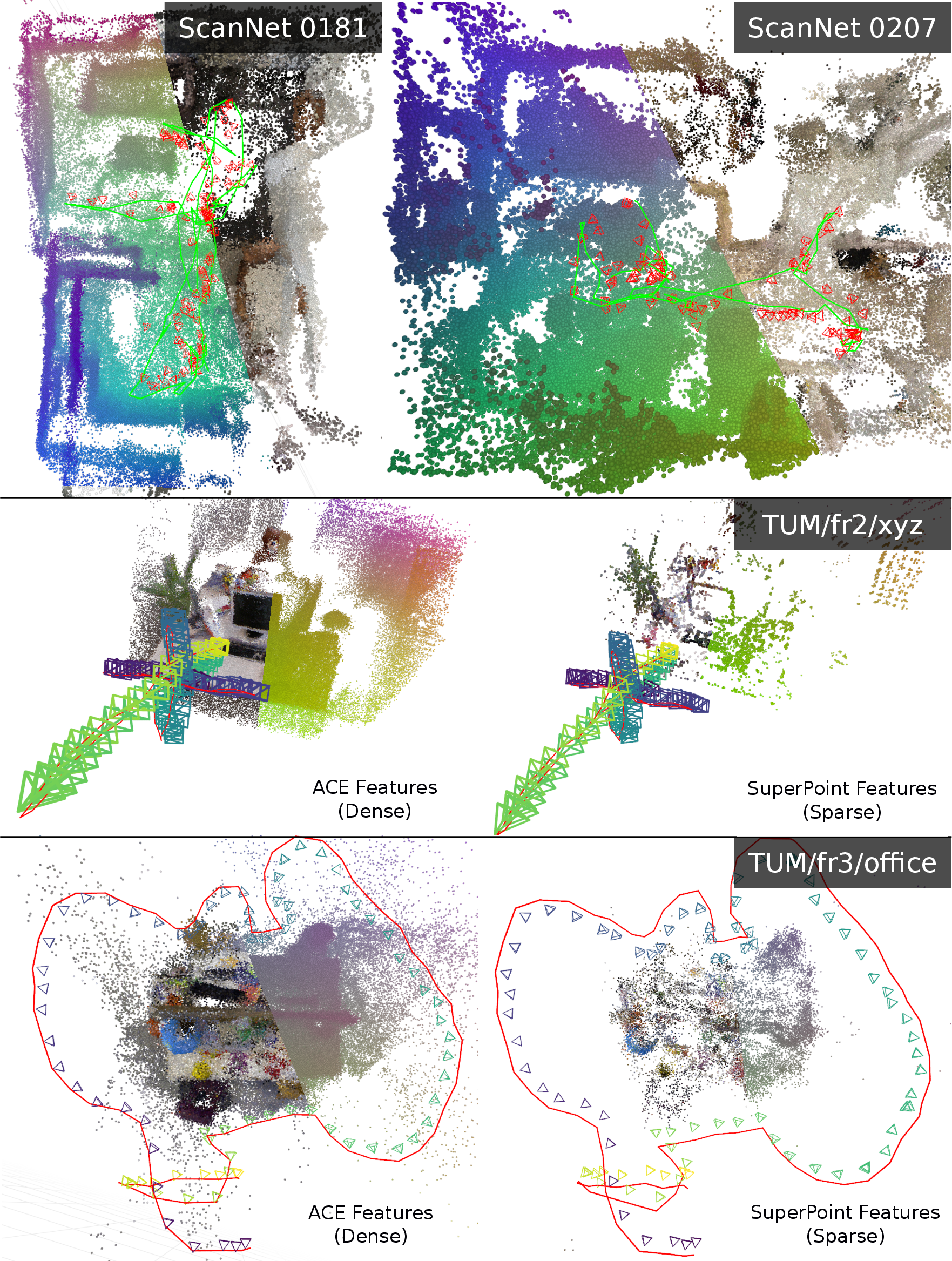

- Flexible features: It works with both dense features (many points across the image) and sparse features (fewer, stronger points). Dense features generally gave better results here.

- Better network design: TriMLP outperformed a standard “direct regression” design (HomMLP) in this setting, showing that the triplane voting idea helps real-time learning and tracking.

Why does this matter?

- Faster, lighter SLAM: This approach shows you can get real-time neural SLAM with tiny maps, which is great for robots, drones, or AR glasses that have limited compute and memory.

- Practical reliability: Quick relocalization and loop closure make it stable in real use—when you turn around, move fast, or walk back into a room, the system keeps up.

- Less complexity: ACE-SLAM achieves these results without many extra modules (like big pre-trained trackers or heavy rendering), simplifying the system.

- Privacy by design: Since the map lives inside a neural network that only outputs world coordinates when given image features from the scene, it’s harder to misuse than storing raw images.

- A new direction: It suggests that Scene Coordinate Regression—a simple “feature-to-3D” mapping—can be a strong alternative to rendering-based neural maps, inspiring future work that improves accuracy without sacrificing real-time performance.

In short, the paper shows a practical, real-time SLAM system that is fast, compact, and robust—using a clever way to learn “where things are” from what the camera sees, and doing so without heavy graphics or complex extra modules.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, phrased to guide actionable future research.

- Scale and environment diversity: No evaluation beyond room-scale, indoor scenes (Replica, TUM, ScanNet); behavior on large-scale buildings, outdoor environments, long corridors, and multi-floor scenarios is unknown.

- Embedded/edge viability: Real-time claims are demonstrated on an RTX 4090; performance, energy, and latency on embedded/edge hardware (e.g., mobile GPUs, Jetson, AR headsets) remains untested.

- RGB-only operation: The pipeline depends on depth to unproject features; feasibility, accuracy, and stability of RGB-only variants (e.g., with depth priors or monocular scale handling) are not evaluated.

- Long-term and multi-session mapping: No experiments on continual mapping across days, repeated sessions, or significant scene changes (rearrangements, seasonal/lighting changes) and how the model handles drift, aging, or re-anchoring.

- Catastrophic forgetting and map stability: While the inlier ratio monitors degradation, there is no analysis or mitigation strategy (e.g., replay buffers, regularization, or dual-memory) to prevent forgetting over long runs.

- Explicit loop closure and global consistency: Loop closure is “soft” via shared map parameters; lack of explicit pose-graph optimization or global BA leaves open questions on closing large loops and correcting long-range drift.

- TriMLP discretization effects: Sensitivity of accuracy to triplane grid resolution (rX, rY, rZ), quantization artifacts, and scaling of memory/compute with larger coordinate ranges are not studied.

- Uncertainty modeling: The model outputs point estimates without per-feature uncertainty; lack of confidence/covariance limits principled weighting in RANSAC and mapping, and prevents uncertainty-aware pose estimation.

- RANSAC design and robustness: Fixed inlier thresholds and hypothesis counts (H) lack sensitivity analysis; adaptive thresholds or robust estimators (M-estimators, DSAC) might improve reliability in noisy or low-overlap conditions.

- Cold-start behavior: How the system bootstraps from an untrained SCR map (initial frames, first relocalizations, failure modes) is not quantified; criteria for reliable initialization are unspecified.

- Feature extractor dependence: Only ACE and SuperPoint (frozen) are tested; no study of other dense/sparse descriptors, descriptor dimensionality, or joint online feature-map co-adaptation.

- Ignoring depth in feature descriptors: Depth is used only to form local 3D points; potential gains from RGB-D features or depth-aware descriptors (e.g., ACEZero-like depth priors) remain unexplored.

- Explicit correspondence vs. implicit matching: The approach eschews explicit correspondences; the trade-offs between implicit matching (via SCR) and hybrid schemes with selective explicit matching are not evaluated.

- Dynamic scene limits: Robustness is shown on TUM dynamic sequences, but failure modes under severe/structured dynamics (crowds, large moving objects, non-rigid surfaces) and object-level motion modeling are not analyzed.

- Photometric/appearance changes: No experiments on substantial illumination changes (day/night, HDR, flicker), motion blur, rolling shutter, or exposure changes common in handheld/mobile scenarios.

- Camera calibration robustness: Assumes known intrinsics; sensitivity to calibration errors, online intrinsics refinement, or auto-calibration is not examined.

- Trajectory–accuracy trade-offs under strict real-time: Frame skipping maintains real-time, but the accuracy impact vs. processing budgets (window size, batch count, hypothesis count) is not systematically characterized.

- Optimization schedule and hyperparameters: No ablation on optimization window composition (|Wnew|, |Wold|), sampling probabilities (α, β), batch size (B), number of batches (NB), or learning rates and their stability.

- Map growth and memory scaling: Although maps are small for room-scale scenes (~1 MB), how memory scales with larger or multi-room environments—and whether submapping or hierarchical schemes are needed—is unclear.

- TriMLP learning dynamics: Lack of ablations comparing classification-voting vs. direct regression beyond HomMLP, alternative bases (learned vs. fixed), different plane parameterizations, or multi-modal outputs (mixtures).

- Handling multi-modality/ambiguity: The triplane voting averages predictions; capability to represent multi-modal hypotheses (e.g., symmetric structures) and its effect on pose estimation remains untested.

- Geometry quality: Quantitative geometry metrics (surface accuracy/completeness vs. GT) are not reported in the main text; how SCR geometry supports downstream tasks (planning, interaction) is uncertain.

- Fair real-time benchmarking protocols: Baseline methods are not run under the same strict real-time/frame-dropping constraints; standardized protocols for accuracy vs. wall-clock under enforced real-time are needed.

- IMU/odometry integration: The system is vision-only; benefits of fusing inertial/odometric priors for robustness under fast motion or feature-poor scenes are open.

- Robustness to sensor noise and artifacts: Effects of depth noise, missing depth (e.g., reflective/transparent surfaces), depth bias, and time-of-flight artifacts on mapping and relocalization are not analyzed.

- Pose and map joint optimization: Poses are estimated via RANSAC+Kabsch and then held fixed during map updates; potential gains from iterative joint optimization (with uncertainty-aware weighting) are not measured.

- Keyframe selection policy: Heuristics for keyframe insertion (Δt, inlier threshold τ) lack a sensitivity study; adaptive policies or learning-based schedulers may improve coverage and stability.

- Privacy claims: The privacy-preserving assertion (map usable only via in-scene images) is not empirically validated (e.g., inversion risks, membership/property inference, leakage via adversarial query features).

- Failure detection and recovery: Apart from inlier ratio, there is no explicit mechanism for tracking failure detection, recovery strategies, or safety fallbacks in prolonged low-quality observations.

- Multi-agent and multi-session fusion: Extending SCR maps across agents/sessions, map merging, and conflict resolution without centralized BA remains an open design space.

- Interoperability with explicit maps: How to export/import SCR maps to/from explicit representations (meshes, splats) for downstream tasks, and the fidelity-cost trade-offs, are not addressed.

- Generalization beyond scene-specific training: While SCR generalization has been explored in other works (ACE-G, MACE), this system remains scene-specific; zero-shot or few-shot adaptation remains untested within ACE-SLAM.

Glossary

- Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE): A metric that quantifies the difference between an estimated trajectory and ground truth over time; lower values indicate better accuracy. Example: "We evaluate trajectory accuracy using \ac{ATE} \ac{RMSE} against ground-truth trajectories with EVO~\cite{grupp2017evo}."

- ACE: A fast scene coordinate regression approach that dramatically reduces training time through improved sampling and self-supervision strategies. Example: "culminating in \ac{ACE} \cite{brachmann2023ace}, which reduced training times to minutes."

- ACE-SLAM: The proposed neural RGB-D SLAM system that uses SCR as an implicit map representation to achieve strict real-time performance. Example: "We present ACE-SLAM, the first neural implicit RGB-D system that uses \ac{SCR} as its core map representation."

- Bundle adjustment: Nonlinear optimization that jointly refines camera poses and scene structure to improve geometric consistency. Example: "Additional components are typically needed for loop closure via global or local bundle adjustment and pose graph optimization strategies"

- Differentiable Sample Consensus (DSAC): A differentiable variant of RANSAC enabling end-to-end training of robust estimators within neural networks. Example: "alongside the \ac{DSAC} works"

- Feature planes: 2D planar feature representations used to factorize 3D neural fields for efficient mapping/rendering. Example: "feature planes~\cite{Chen2022TensoRF} in ESLAM~\cite{Johari2023eslam}"

- Gaussian Splatting: A rendering and mapping technique that represents scenes as collections of 3D Gaussian primitives (splats) for efficient visualization. Example: "Gaussian splats and related methods~\cite{Kerbl2023GaussianSplatting,Held2025Triangle,Matsuki2024GaussianSplattingSLAM}"

- HomMLP: A baseline SCR architecture that directly regresses coordinates with an MLP using skip connections and homogeneous outputs. Example: "which we refer to as HomMLP and compare against in \cref{sec:experiments}."

- Homogeneous coordinates: A projective-space representation enabling translations and perspective transformations via linear algebra. Example: "with skip connections and prediction of homogenous coordinates,"

- Inlier ratio: The proportion of correspondences consistent with a model (e.g., a pose) used to select the best hypothesis in robust estimation. Example: "and the one with the largest inlier ratio is selected:"

- Inverse rendering: Optimizing scene parameters by rendering predictions and matching them to observations for self-supervised learning. Example: "optimized via self-supervision with inverse rendering,"

- Kabsch–Umeyama algorithm: A closed-form least-squares method for estimating a rigid transformation between two point sets. Example: "using the Kabsch-Umeyama algorithm~\cite{Umeyama1991LeastSquares}."

- Keyframe: A selected frame whose pose and features are used for optimization and map updates in SLAM. Example: "A frame becomes a keyframe if more than $$ time has elapsed since the last keyframe insertion,"</li> <li><strong>Loop closure</strong>: The process of recognizing previously visited places to correct drift and enforce global consistency. Example: "natively supports key \ac{SLAM} functionalities such as implicit loop closure and relocalization"</li> <li><strong>Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)</strong>: A feed-forward neural network used to regress scene coordinates from image features. Example: "Conventional \ac{SCR} networks typically employ simple \acp{MLP} that directly regress 3D coordinates from input features."</li> <li><strong>NeRF (Neural Radiance Fields)</strong>: A neural representation that models radiance and density for novel view synthesis via volumetric rendering. Example: "volumetric rendering pipelines following the rise of \ac{NeRF} \cite{Mildenhall2020NeRF, Muller2022InstantNGP}."</li> <li><strong>Optimization window</strong>: The subset of frames chosen for each optimization cycle to update poses and the map. Example: "denoted as the optimization window $\OptimizationWindow$."

- Parallel Tracking and Mapping (PTAM): A strategy that runs tracking and mapping in parallel threads to improve real-time performance. Example: "parallel tracking-and-mapping strategy~\cite{Klein2007PTAM}"

- Point-NeRF: A NeRF variant that leverages point cloud support to represent radiance fields. Example: "Point-\ac{NeRF}~\cite{Xu2022PointNeRF} in Point-SLAM~\cite{Sandstrom2023pointslam}."

- Pose graph optimization: Graph-based optimization that adjusts poses using loop-closure and other constraints to maintain global consistency. Example: "pose graph optimization strategies"

- RANSAC (Random Sample Consensus): A robust estimation algorithm that selects model parameters by maximizing inliers across random samples. Example: "we apply \ac{RANSAC}~\cite{Fischler1981RANSAC}."

- Ray integration: Sampling and integrating along camera rays through a volume to render images or extract geometry. Example: "bypassing the need for ray integration"

- Relocalization: Estimating the camera pose in a known map from a single frame, even after tracking loss. Example: "enable extremely fast relocalization,"

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): An aggregate error measure equal to the square root of the mean of squared errors. Example: "We evaluate trajectory accuracy using \ac{ATE} \ac{RMSE} against ground-truth trajectories with EVO~\cite{grupp2017evo}."

- Scene Coordinate Regression (SCR): Learning to map 2D image features directly to 3D scene coordinates for efficient localization and mapping. Example: "we investigate the use of Scene Coordinate Regression (SCR)~\cite{shotton2013scr_forest} as an alternative implicit neural scene representation"

- Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM): Building a map while estimating the sensor’s pose within it. Example: "In visual \ac{SLAM}, efficiency and robustness are often just as important as accuracy,"

- Softmax: A function that converts logits into a probability distribution over discrete classes. Example: "C_i{XY}, C_i{XZ}, C_i{YZ} = \mathrm{softmax}(\mathrm{MLP}(_i)),"

- TriMLP: The paper’s triplane-based SCR network that votes over discretized bases on three planes to predict 3D coordinates. Example: "referred to as TriMLP, that factorizes 3D coordinate regression into three orthogonal 2D classification problems."

- Triplane: A representation that factorizes 3D information across three orthogonal 2D planes to simplify learning and inference. Example: "a lightweight triplane-based alternative, referred to as TriMLP,"

- Volumetric rendering: Rendering by integrating densities and colors along rays through a volume. Example: "volumetric rendering pipelines"

- Voxel-based feature grids: 3D grids of learned features used as efficient neural scene representations. Example: "using voxel-based feature grids \cite{Muller2022InstantNGP} in NICE-SLAM~\cite{Zhu2022NICE-SLAM},"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are actionable, deployable use cases that can be implemented now using ACE-SLAM’s SCR-based, compact, privacy-preserving, real-time RGB-D SLAM pipeline and TriMLP architecture.

- On-device SLAM for AR headsets and smartphones (consumer electronics, software)

- What: Real-time mapping and relocalization for AR scene anchoring, furniture placement, and persistent content.

- Tools/products/workflows: ACE-SLAM SDK; Unity/Unreal plugin; on-device map training with TriMLP; native relocalization for fast “return-to-scene.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: RGB-D sensor (e.g., HoloLens, iPhone LiDAR/ToF), calibrated intrinsics, moderate GPU/NPUs; accuracy below top NeRF-based SLAM but sufficient for real-time anchoring; dynamic scene robustness without semantic masking.

- Real-time localization for mobile robots in dynamic indoor environments (robotics)

- What: Robust navigation and relocalization in workplaces/hospitals/offices where people move through the robot’s field of view.

- Tools/products/workflows: ROS2 node for ACE-SLAM; plug-in localization back-end in existing stacks; online map update with keyframe windowing; always-on RANSAC+Kabsch relocalization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: RGB-D camera (Intel RealSense, Azure Kinect), known intrinsics; compact maps (~1 MB/room) facilitate fleet-wide deployment; loop-closure is “soft” rather than explicit; accuracy competitive but not SOTA on all sequences.

- Privacy-preserving home mapping for consumer robots (consumer robotics)

- What: Room maps for path planning and coverage that minimize privacy risk (map weights only useful when accompanied by scene imagery).

- Tools/products/workflows: “Private Mapping Mode” in robot vacuums; on-device map storage; weight-only sharing between sessions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy benefit relies on SCR requiring image descriptors to query geometry; risk assessment still needed (e.g., potential descriptor spoofing).

- Handheld mapping and worker navigation on shop floors and warehouses (logistics/retail)

- What: On-device, fast, compact mapping for ad-hoc inventory audits, aisle relocalization, and worker guidance amidst dynamic crowds.

- Tools/products/workflows: Android/iOS app with ACE-SLAM; session-based map (~MB scale) per zone; quick relocalization without cloud.

- Assumptions/dependencies: RGB-D phones/tablets or lightweight depth add-ons; stable lighting and texture; throughput depends on device inference capabilities.

- Telepresence and MR boundary setup (AR/VR)

- What: Rapid relocalization for returning users; persistent room boundaries and safety zones.

- Tools/products/workflows: MR safety calibration app using ACE-SLAM; lightweight map caching per room.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Depth-enabled HMD; moderate compute; robust tracking even with moving participants.

- Indoor navigation aids for visually impaired users (healthcare, wearables)

- What: On-device scene mapping and robust relocalization to support spatial audio guidance in dynamic corridors.

- Tools/products/workflows: Wearable RGB-D device; ACE-SLAM back-end; audio cues linked to stable global coordinates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Depth sensor, battery budget; reliability depends on feature coverage and device power.

- Strict real-time evaluation and benchmarking standardization (academia)

- What: Adopt RT-Factor and map-size reporting; promote SCR-based baselines that meet frame-rate constraints.

- Tools/products/workflows: Open-source ACE-SLAM code and evaluation templates; curriculum use in SLAM courses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of comparable hardware or normalized RT-Factor reporting; reproducibility across datasets.

- Lightweight SLAM back-end for existing frameworks (software)

- What: Swap NeRF-based implicit mapping with SCR/TriMLP to achieve real-time and compact maps on edge hardware.

- Tools/products/workflows: ACE-SLAM plugin for OpenVSLAM/ORB-SLAM3/ROS2; simplified integration via RGB-D and feature extractor.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Feature extractor frozen; accuracy targets adjusted for real-time; no explicit bundle adjustment/loop closure modules included.

- Compliance-oriented on-device mapping (policy, privacy)

- What: Data-minimization strategy by keeping mapping on-device; share only compact weights when needed.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Privacy Mode” toggle; DPIA templates citing implicit access gating via scene imagery.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal reviews needed; risk remains if descriptors can be synthesized; no formal privacy proof yet.

- Energy/battery savings via efficient relocalization (energy, wearables/AR)

- What: Reduce compute/battery use with pixel-independent coordinate regression and small maps.

- Tools/products/workflows: Power profiling and dynamic feature sampling; adaptive windowing based on inlier ratios.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Gains contingent on device accelerators (GPU/NPU) and careful scheduling; performance measured per device class.

- Robust tracking in dynamic factory floors (industrial robotics)

- What: Maintain localization with moving workers/robots without semantic segmentation modules.

- Tools/products/workflows: ACE-SLAM drop-in localization; implicit outlier rejection via RANSAC in relocalization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Safety-critical deployments still need redundancy; explicit loop closure/BA may be required for large-scale operations.

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities require further research, scaling, or engineering to reach production readiness.

- RGB-only operation via depth priors or monocular depth (mobile AR, consumer electronics)

- What: Remove dependency on hardware depth; support broader phone base.

- Tools/products/workflows: Integrate learned depth priors (ACE-Zero-like); self-supervised feature refinement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accuracy trade-offs in textureless areas; stability under fast motion; additional training.

- Large-scale, multi-floor, and multi-agent collaborative mapping (robotics, smart buildings)

- What: Extend soft loop closure with pose graphs/submaps; team-based mapping with map merging.

- Tools/products/workflows: Distributed ACE-SLAM with submap servers; ROS2 multi-agent coordination; map versioning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scalable relocalization across submaps; communication constraints; explicit global optimization.

- Semantic integration for dynamic-object handling and scene graphs (robotics, AR/VR)

- What: Combine SCR with semantic priors to reject/track dynamic objects and build object-level scene graphs.

- Tools/products/workflows: Semantic masking modules; object SLAM overlays; AR measurement apps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Extra compute; data labeling or self-supervision; potential privacy implications of semantics.

- Formal privacy guarantees and certifications (policy, compliance)

- What: Establish evidence-backed claims that SCR maps are privacy-preserving and non-reversible.

- Tools/products/workflows: Audits, threat models, red-team tests; certification for GDPR/CCPA.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Theoretical analyses of descriptor-to-geometry leakage; new standards and test suites.

- Porting to low-power embedded platforms (wearables, IoT, drones)

- What: Quantized/optimized ACE-SLAM for Jetson/Qualcomm NPUs; INT8 TriMLP; memory-aware feature pipelines.

- Tools/products/workflows: ONNX/TensorRT builds; kernel fusion; adaptive sampling for energy budgets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Performance may dip; careful accuracy–latency trade-offs; device-specific optimization.

- Hybrid pipelines with explicit primitives for visualization (software, media)

- What: Use SCR for localization while Gaussian/Triangle splatting render high-fidelity visuals.

- Tools/products/workflows: Dual-backbone pipeline; SCR for tracking; splats for view synthesis.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Synchronization of representations; added complexity; memory growth.

- Session-to-session map sharing and federated relocalization (consumer electronics, enterprise)

- What: Persist maps across visits; share minimal map weights with teams while preserving privacy.

- Tools/products/workflows: Map fingerprinting; encrypted weight sharing; federated learning of features.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stability of features across sessions; secure key exchange; device heterogeneity.

- Test-time feature learning and domain adaptation (academia, software)

- What: Online refinement of feature extractors to improve implicit matching and accuracy.

- Tools/products/workflows: Self-supervised updates; curriculum learning; uncertainty-aware sampling.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Risk of drift/overfitting; stability safeguards; compute overhead.

- Outdoor and aerial SLAM (drones, autonomous platforms)

- What: Extend SCR robustness to fast motion, lighting changes, and outdoor texture variation.

- Tools/products/workflows: High-frame-rate cameras; motion-compensated sampling; multi-sensor fusion (IMU/LiDAR).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Depth availability outdoors; sensor fusion design; weather/illumination challenges.

- Object-centric measurement and digital twin workflows (AEC/FM, industry)

- What: Integrate ACE-SLAM with CAD/BIM for quick annotations and measurements; persistent object anchors.

- Tools/products/workflows: BIM connectors; scene-coordinate anchors for assets; inspection apps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scale and accuracy improvements; semantic alignment; regulatory constraints in construction.

- Regulatory guidance for on-device spatial AI (policy)

- What: Develop best-practice guidelines for edge mapping, data minimization, and secure map sharing.

- Tools/products/workflows: Industry consortia position papers; standardized benchmarks and reporting (RT-Factor, map size).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stakeholder alignment; evolving privacy law; cross-vendor interoperability.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.