Fostering human learning is crucial for boosting human-AI synergy (2512.13253v1)

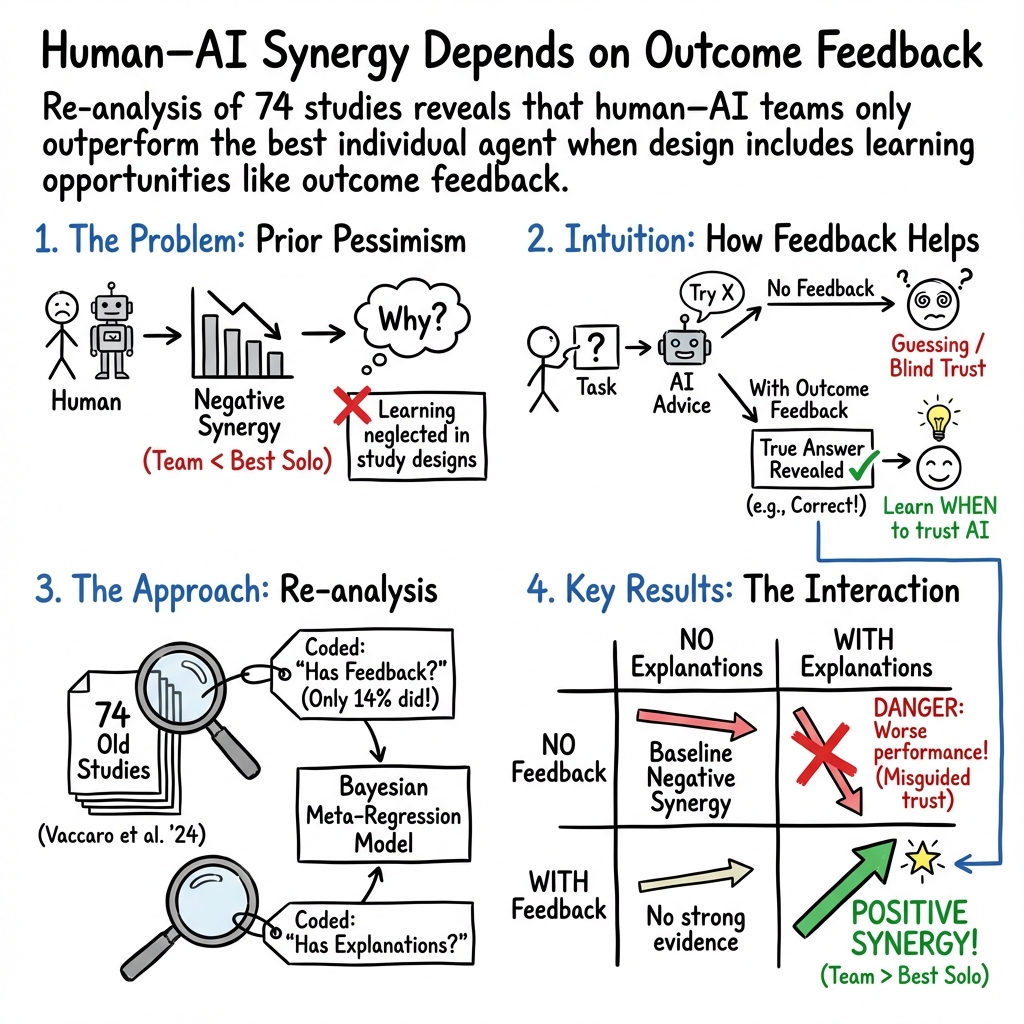

Abstract: The collaboration between humans and AI holds the promise of achieving superior outcomes compared to either acting alone. Nevertheless, our understanding of the conditions that facilitate such human-AI synergy remains limited. A recent meta-analysis showed that, on average, human-AI combinations do not outperform the better individual agent, indicating overall negative human-AI synergy. We argue that this pessimistic conclusion arises from insufficient attention to human learning in the experimental designs used. To substantiate this claim, we re-analyzed all 74 studies included in the original meta-analysis, which yielded two new findings. First, most previous research overlooked design features that foster human learning, such as providing trial-by-trial outcome feedback to participants. Second, our re-analysis, using robust Bayesian meta-regressions, demonstrated that studies providing outcome feedback show relatively higher synergy than those without outcome feedback. Crucially, when feedback is paired with AI explanations we tend to find positive human-AI synergy, while AI explanations provided without feedback were strongly linked to negative synergy, indicating that explanations are useful for synergy only when humans can learn to verify the AI's reliability through feedback. We conclude that the current literature underestimates the potential for human-AI collaboration because it predominantly relies on experimental designs that do not facilitate human learning, thus hindering humans from effectively adapting their collaboration strategies. We therefore advocate for a paradigm shift in human-AI interaction research that explicitly incorporates and tests human learning mechanisms to enhance our understanding of and support for successful human-AI collaboration.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper looks at how people and AI can work together as a team and do better than either one working alone. The authors argue that many past studies gave a too-negative picture of human–AI teamwork because they didn’t let people learn during the task. They re-examined 74 studies and found that giving people feedback (like telling whether their answer was right after each trial) can boost teamwork with AI—especially when the AI also provides explanations.

What questions did the researchers ask?

The researchers asked simple, practical questions:

- Why do many studies say human–AI teams don’t beat the best solo performer?

- Does letting humans learn during the task (by giving outcome feedback) improve teamwork with AI?

- Do AI explanations help—and if so, do they only help when people also get feedback that lets them check how reliable the AI is?

How did they study it?

They re-analyzed data from a large, recent review of 74 studies that compared:

- Humans working alone,

- AI working alone,

- Humans and AI working together on the same task.

Common tasks included things like classifying images, predicting outcomes (such as game results), and writing code.

To understand what helps people learn, the authors looked for study design features like:

- Outcome feedback: Did participants learn the correct answer after each trial?

- AI explanations: Did the AI explain how it reached its suggestion?

They used a statistical approach called “robust Bayesian meta-regression.” In everyday terms:

- “Meta-analysis” means combining results from many studies to see overall patterns.

- “Bayesian” methods treat evidence like a “confidence meter” that updates as you see more data.

- “Model averaging” means trying many reasonable statistical models and blending them, so no single model’s assumptions dominate the result.

They measured “synergy” using a score called Hedges’ g:

- Think of Hedges’ g as a difference score where 0 means “no advantage.”

- Positive values mean the human–AI team did better than the best solo performer.

- Negative values mean the team did worse than the best solo performer.

They also reported “credible intervals” (a likely range for the true value) and “Bayes factors” (how strongly the data support a non-zero effect). You can think of Bayes factors as a strength-of-evidence gauge.

What did they find?

Big picture: Most studies did not help people learn during the task. For example, there were usually no practice trials and no outcome feedback. Only 10 out of 74 studies gave feedback, and just 3 tracked how performance changed over time.

Key results:

- Without feedback, human–AI synergy tended to be negative (about −0.17), meaning teams often did worse than the best solo performer.

- With feedback, synergy was around zero to slightly positive (about +0.12), suggesting teams could match or beat the best solo performer.

- The strongest pattern appeared when AI explanations were paired with feedback:

- Explanations + feedback: synergy tended to be positive (about +0.30).

- Explanations but no feedback: synergy was clearly negative (about −0.31).

What this means:

- Explanations alone can backfire if people can’t check whether the AI is right. It’s like getting a “reason” but no way to see if that reason leads to correct answers.

- Explanations plus outcome feedback help people learn when to trust the AI and when to rely on themselves, making the team smarter over time.

Caution:

- Some results were “tentative” because not many studies offered feedback, and most didn’t track learning across trials. Still, the pattern is consistent: learning opportunities matter.

Why does this matter?

If we want human–AI teams to truly shine, we should:

- Give people feedback so they can learn which signals are reliable.

- Pair feedback with helpful AI explanations that point attention to the most relevant features.

- Design experiments that allow learning across multiple trials and report standard performance metrics so others can analyze them.

This matters for real-world use (medicine, safety checks, hiring, customer support, coding, and more): better-designed teamwork can improve accuracy, fairness, and trust.

Takeaway and potential impact

The main takeaway is simple: Fostering human learning is crucial for successful human–AI teamwork. Studies that don’t allow learning may underestimate what human–AI teams can achieve. Future research should build tasks with feedback, explanations, practice opportunities, and clear metrics. Doing this could turn human–AI collaboration from “often worse than the best solo performer” into “consistently better together.”

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single list of concrete gaps and questions the paper leaves unresolved that future research can directly address.

- Causal effect of outcome feedback: The re-analysis relies on observational variation; no included study experimentally manipulated the presence, timing, frequency, or granularity of feedback. Design factorial RCTs that orthogonally vary feedback (none vs per-trial vs periodic), timing (immediate vs delayed), and content (correctness-only vs enriched rationales) to estimate causal impacts on human–AI synergy.

- Learning trajectories over time: Only 3 of the 10 feedback studies reported trial-level dynamics; most analyses use averages across trials. Collect and analyze trial-by-trial logs to model learning curves, switching behavior between self and AI advice, and convergence rates under different learning supports over multi-session studies.

- Explanation × feedback interaction mechanisms: While explanations paired with feedback correlate with higher synergy, the mechanism is untested. Compare explanation types (feature importance, exemplars, counterfactuals, rationales), their fidelity, and cognitive load, with and without feedback, to isolate why explanations without feedback hurt synergy and which combinations help.

- Confounding study design heterogeneity: Conditions with feedback may systematically differ (task difficulty, domain, incentive schemes, advice sequence, participant expertise). Conduct meta-regressions controlling for these moderators and run controlled experiments that cross these variables to separate feedback effects from design confounds.

- Magnitude and precision of effects: Estimates for synergy with and without feedback have wide credible intervals that often include zero, and the number of feedback studies is small. Run larger, preregistered studies to obtain precise effect-size estimates and reduce uncertainty.

- Broader evidence base: The corpus is dominated by recent HCI studies; relevant work in human factors and judgment/decision-making (pre-2018) is underrepresented. Perform comprehensive systematic reviews with broader search terms and time windows to test whether learning-centered conclusions generalize.

- Standardized reporting and metrics: Many studies lack the performance metrics needed to compute synergy. Develop and adopt a reporting standard that includes human-only, AI-only, and hybrid performance on consistent metrics (accuracy, calibration, cost-sensitive utility) and share trial-level data.

- Synergy definition robustness: The analysis uses Hedges’ g relative to the best single agent; this may obscure cost–benefit tradeoffs and domain-specific utility. Evaluate alternative synergy formulations (e.g., excess utility over weighted baselines, cost-sensitive or risk-aware metrics, calibration improvements) and test whether learning effects persist under these definitions.

- Incentive effects: Performance-based incentives are present in some studies but not analyzed as moderators. Experimentally vary incentive structures (none vs individual vs team-based vs cost-sensitive) to test their impact on learning and synergy.

- Participant expertise and domain knowledge: The role of expertise in leveraging feedback and explanations is unknown. Stratify samples by expertise (novices vs professionals) and examine how domain knowledge moderates learning speed, strategy adaptation, and final synergy.

- Task diversity: Most tasks are classification/decision; creative, generative, planning, and interactive tasks are scarce. Test whether learning supports (feedback/explanations) produce synergy in non-classification domains and under open-ended outcomes.

- Advice timing and interaction mode: Concurrent, sequential, on-demand, and time-delayed advice sequences are present but not analyzed as learning moderators. Manipulate advice timing to quantify its effects on verification opportunities, trust calibration, and performance.

- Uncertainty communication: The combined effect of AI confidence/uncertainty displays with feedback and explanations is underexplored. Test whether calibrated uncertainty signals accelerate learning and improve selective reliance on AI.

- Process measures of learning: The hypothesized attention-guidance effect of explanations is not directly measured. Use eye-tracking, behavioral process tracing, think-aloud protocols, and cognitive load measures to verify how explanations and feedback change feature attention and integration strategies.

- Feedback feasibility in domains with delayed or unavailable ground truth: Guidance is needed for high-stakes domains where immediate outcomes are unknown. Evaluate surrogate feedback (simulation outcomes, expert adjudication, probabilistic outcome forecasts), their reliability, and their impact on learning and trust.

- Feedback quality and noise: The effects of incorrect, noisy, or delayed feedback are not examined. Study robustness of learning and synergy to feedback imperfections and develop methods to mitigate mislearning from noisy labels.

- Team and organizational contexts: The analysis focuses on individuals; how feedback/explanations affect team-based human–AI collaboration is unknown. Investigate group-level learning, aggregation strategies, and division of labor with AI, including how feedback should be targeted (individual vs team).

- Ethical and psychological outcomes: Trust calibration, overreliance, and illusion of understanding with explanations (especially without feedback) are hypothesized but unmeasured. Measure trust dynamics, overconfidence, and reliance strategies alongside performance to ensure beneficial and safe learning.

- Publication bias and model specifications: Although RoBMA addresses bias, sensitivity to prior choices, model structures, and inclusion criteria is not reported. Provide comprehensive sensitivity analyses and robustness checks to alternative priors and model configurations.

- Coding reliability and reproducibility: The added study-feature coding may be subjective; inter-rater reliability statistics and detailed codebooks are not reported in the main text. Publish agreement metrics, coding protocols, and independent replication of coding to strengthen confidence in moderator analyses.

- Multi-objective performance: Synergy may vary across accuracy, speed, cost, and error severity; most studies report single metrics. Collect multi-metric outcomes and analyze trade-offs to understand how learning supports shift efficiency–accuracy frontiers.

- Learning supports beyond outcome feedback: Practice trials, tutorials, scaffolding, and adaptive training are coded but not analyzed. Test their independent and combined effects on learning and synergy relative to outcome feedback.

- Adaptive AI that learns from the human: How AI should adjust explanations, confidence, and advice timing in response to observed human learning is not addressed. Develop and evaluate algorithms for bi-directional adaptation (user modeling, personalized explanation policies) to optimize synergy over time.

- Data availability for learning analyses: The lack of trial-level data prevents detailed learning modeling. Encourage sharing of raw per-trial logs, interaction traces, and timing data to enable fine-grained analyses of learning and strategy adaptation.

Glossary

- Algorithm aversion: The tendency to prefer human judgment over algorithmic recommendations, potentially leading to underuse of AI assistance. "algorithm aversion versus appreciation"

- Bayes factor: A measure of evidence comparing two hypotheses, defined as the ratio of the likelihood of the data under each; larger values favor one hypothesis over the other. "Bayes factors (BF) quantify the relative evidence for the two competing hypotheses that the estimate is non-zero versus zero."

- Bayesian meta-regression: A meta-analytic regression model estimated using Bayesian inference to assess how moderators relate to effect sizes across studies. "robust Bayesian meta-regressions"

- Conditional marginal posterior: The posterior distribution of an estimated quantity, conditioned on a model and marginalized over parameters, used for inference on effects. "conditional marginal posterior estimates of Hedge's effect size"

- Credible interval: A Bayesian interval within which a parameter lies with a specified posterior probability (e.g., 95%). "95 credible intervals [CI] to 0.00"

- Design space: The set of possible experimental configurations and choices (tasks, feedback, timing, incentives) that shape human–AI interaction studies. "design space of possible human--AI decision-making experiments"

- Effect size: A quantitative measure of the magnitude of a phenomenon, often used to compare groups or conditions across studies. "using Hedge's effect size to measure the standardized difference in performance"

- Explainable AI: Methods that make AI outputs and reasoning understandable to humans, often by highlighting relevant features or steps. "Explainable AI may likewise help humans focus on relevant task features---and even indicate how the AI uses those features to predict the outcome---and thus facilitate human learning"

- Gelman–Rubin criterion (R-hat): A convergence diagnostic for MCMC; values close to 1 (e.g., < 1.05) indicate that chains have mixed and converged. "Convergence was checked using the Gelman--Rubin criterion 1.05"

- Hedges' g: An unbiased standardized mean difference used as an effect size in meta-analysis, correcting for small sample bias. "Hedges' "

- Hierarchical model: A statistical model with parameters structured across multiple levels (e.g., effect sizes within experiments within studies). "three-level hierarchical model structure"

- Meta-analysis: A statistical technique that synthesizes results across multiple studies to estimate overall effects. "preregistered systematic review and meta-analysis of 74 studies"

- Meta-regression: A meta-analytic technique that models effect sizes as a function of study-level moderators. "meta-regressions evaluating moderation effects"

- Moderator: A variable that influences the strength or direction of an effect in analysis. "quantifying the evidence that outcome feedback moderates human--AI synergy"

- Posterior median: The median of the posterior distribution, often used as a point estimate for parameters. "using the posterior median (point estimate)"

- Probability of direction (PD): The posterior probability that an effect is strictly positive or strictly negative. "posterior probability of [a positive] direction (PD) = 84"

- Publication bias: Distortion in the evidence base caused by selective publication of certain results (e.g., significant findings). "absence versus presence of publication bias"

- Robust Bayesian Model Averaging (RoBMA): A Bayesian framework that averages over multiple models while accounting for issues like publication bias to yield robust meta-analytic estimates. "Robust Bayesian Model Averaging (RoBMA; Rpackage version 3.5)"

- Spike-and-slab algorithm: A Bayesian variable selection approach that mixes a “spike” prior (near zero) with a “slab” prior (diffuse), enabling sparse modeling. "spike-and-slab algorithm"

- Systematic review: A structured, comprehensive literature review conducted with predefined inclusion criteria and methods. "preregistered systematic review and meta-analysis"

Practical Applications

Below is a concise synthesis of practical applications that follow from the paper’s core insight: human–AI synergy improves when systems pair actionable outcome feedback with AI explanations, creating conditions for human learning and adaptive reliance. The lists are grouped into immediate and long-term opportunities, and each item notes sector(s), potential tools/workflows, and key assumptions/dependencies.

Immediate Applications

The following can be deployed now with existing systems and data, primarily by adding a “feedback layer” and adapting user interfaces and evaluation practices:

- Human–AI decision-support interfaces with trial-level feedback and explanation coupling (software, HCI, operations)

- What: Add per-case outcome feedback (when ground truth is known) and display explanations alongside AI outputs (feature importance, rationales).

- Tools/workflows: Feedback Layer SDK; Explanation-Feedback Coupler; Synergy Logging & Analytics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable, timely ground truth; explanations that reflect model behavior; tasks with repeat exposure.

- A/B tests comparing “explanations + feedback” versus “explanations only” conditions (industry, academia)

- What: Run controlled evaluations to detect whether explanations help only when feedback exists, as the paper’s meta-regression suggests.

- Tools/workflows: Experimentation platform; standardized synergy metrics (e.g., Hedges’ g); trial-level telemetry.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consistent labeling protocol; enough statistical power; task performance is measurable.

- Reliance calibration training for analysts (finance, security, trust & safety, e-commerce)

- What: Short calibration modules where analysts practice on labeled historical cases, receive immediate feedback, and learn when to defer to AI.

- Tools/workflows: Adaptive Reliance Trainer; case-type routing scenarios; confidence overlays with feedback-driven calibration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Labeled case libraries; incentive alignment; UI support for confidence and feedback display.

- Simulation-based practice environments with immediate feedback (energy grid ops, logistics, aviation ops)

- What: Use simulators that provide ground-truth outcomes for operator decisions made with AI assistance, pairing explanations and feedback.

- Tools/workflows: Digital twin simulators; scenario banks with known outcomes; performance dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-fidelity simulations; accurate proxies for real-world outcomes; session logging for learning curves.

- Code assistant workflows that auto-generate feedback via tests (software engineering)

- What: After accepting or editing AI code suggestions, run unit/integration tests to give outcome feedback; show explanations (diffs, static analysis).

- Tools/workflows: Test-run feedback triggers; explanation overlays (linters, type-checker rationale); per-commit synergy tracking.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust test suites; CI/CD integration; developers accept structured feedback loops.

- Quality-control stations with immediate pass/fail feedback (manufacturing, recycling, X-ray screening)

- What: Pair AI classification with on-the-spot verification (e.g., re-inspection, test scans), training humans to trust/override appropriately.

- Tools/workflows: Inline verification devices; per-item feedback banners; case-type statistics by operator.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Feasible on-the-spot checks; low latency; consistent labeling standard.

- Tutoring and study tools with formative feedback (education, daily life)

- What: In AI-assisted learning (e.g., practice problems, language learning), show explanations and immediate correctness feedback to build calibrated reliance on AI hints.

- Tools/workflows: Practice engines with auto-grading; explanation-guided hints; learner calibration dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Valid item banks; reliable auto-grading; safeguards against overreliance.

- Procurement and UX checklists for feedback-enabled human–AI systems (policy, product management)

- What: Require that systems specify when and how outcome feedback is available; disallow explanation-only modes when feedback is absent.

- Tools/workflows: Human–AI Synergy Playbook; “feedback availability” rubric; explanation gating policy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational buy-in; clarity on acceptable feedback sources and delays.

- Adoption of robust Bayesian meta-analytic evaluation (academia, R&D)

- What: Use Robust Bayesian Model Averaging (RoBMA) for multi-study synthesis and moderation analysis of learning variables (feedback, explanations).

- Tools/workflows: RoBMA packages; trial-level repositories; standardized reporting templates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Open data; consistent effect-size computation; competence with Bayesian analysis.

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities require further research, scaling, or infrastructural development to deal with delayed ground truth, complex tasks, and governance:

- Continuous learning pipelines that personalize delegation policies (software, operations, healthcare)

- What: Systems learn user- and case-specific patterns of success and adaptively decide when humans or AI should lead, aided by explanations and feedback over time.

- Tools/workflows: Personalized delegation engines; case-type classifiers; longitudinal calibration models.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Longitudinal data; reliable delayed outcomes (e.g., medical diagnoses, claim resolutions); privacy-preserving logging.

- “Synergy audits” and certification for human–AI systems (policy, compliance, procurement)

- What: Regulatory or third-party audits that quantify human–AI synergy and mandate feedback mechanisms and reporting of trial-level metrics.

- Tools/workflows: Synergy Scorecards; audit protocols; sector-specific benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standards for synergy metrics; sector regulators; audit-ready data pipelines.

- Feedback registries and outcome harmonization in healthcare (healthcare, public health)

- What: Build infrastructure to connect AI-assisted decisions to eventual ground truth (e.g., lab results, longitudinal outcomes) to enable learning and calibrated reliance.

- Tools/workflows: Outcome registries; delayed feedback processors; clinician-facing learning dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data interoperability (EHRs); governance for sensitive outcomes; acceptable delay windows.

- Explanation gating and adaptive information disclosure (HCI, policy, safety-critical systems)

- What: Only show explanations when verifiable feedback will follow; adapt the amount/type of explanation to user’s learning stage and case characteristics.

- Tools/workflows: Gating policies; adaptive explanation controllers; UI telemetry-driven personalization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable detection of feedback availability; validated explanation taxonomies; user modeling.

- Workforce curricula for learning-with-AI (education, professional training)

- What: Standardized training that includes repeated practice, immediate/delayed feedback, and explanation literacy to build adaptive strategies for AI reliance.

- Tools/workflows: Sector-specific curricula; simulation modules; competency assessments tied to synergy improvements.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Employer/sector adoption; accreditation bodies; evidence of transfer to real tasks.

- Multi-session, incentive-aligned study designs for HAI (academia, R&D)

- What: Research protocols that track learning across sessions, include performance-based incentives, and vary feedback types and timings.

- Tools/workflows: Longitudinal trial platforms; mixed-effects analysis pipelines; incentive mechanisms.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Funding for multi-session studies; participant retention; generalizability across tasks.

- Human–AI orchestration platforms with embedded synergy measurement (software, enterprise AI)

- What: Platforms that coordinate multiple AI tools and human roles, logging outcomes to quantify synergy and auto-tune workflows for better joint performance.

- Tools/workflows: Orchestration layer; synergy optimization loops; case routing engines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Enterprise-scale data collection; reliable KPIs; change management for workflow adaptation.

- Risk management for feedback-driven learning (policy, safety, ethics)

- What: Frameworks to mitigate biases introduced by selective or noisy feedback; guardrails against gaming and erroneous labels.

- Tools/workflows: Feedback quality monitors; label provenance tracking; bias audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Label audit infrastructure; stakeholder governance; corrective procedures.

- Sector standards for reporting human–AI interaction metrics (cross-sector policy, academia)

- What: Consensus on minimal reporting (trial counts, feedback presence/type, explanation presence/type, human/AI-only baselines, synergy effect sizes).

- Tools/workflows: Reporting templates; open repositories; cross-field meta-analysis consortia.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community agreement; incentives for data sharing; privacy and IP constraints.

- Delayed-feedback learning frameworks for domains without immediate ground truth (finance, claims, HR)

- What: Methods to learn from outcomes that arrive weeks/months later (e.g., default, claim validity, hire performance) and back-propagate calibration signals to users.

- Tools/workflows: Outcome aging models; delayed feedback attribution; periodic calibration sessions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable identifiers; robust outcome linkage; temporal drift management.

Note on feasibility and dependencies across applications:

- Ground-truth availability and latency: Many domains do not have immediate feedback; where feedback is delayed or noisy, simulation and historical labeled data can be used.

- Explanation quality and faithfulness: Explanations should be validated to avoid misleading users; explanation-only without feedback risks negative synergy, per the paper’s findings.

- Repeated exposure: Learning effects rely on repeated tasks and logging trial-level performance.

- Incentives and UX: Align incentives for careful decision-making and provide UIs that make feedback salient and easy to interpret.

- Privacy, safety, and governance: Feedback loops require data retention and label provenance; compliance frameworks must be in place.

- Standardized measurement: Adoption improves when synergy is measured consistently (e.g., Hedges’ g, trial-level error rates) and reported.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.