Pre-perihelion detection of a wobbling high-latitude jet in the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS (2512.12819v1)

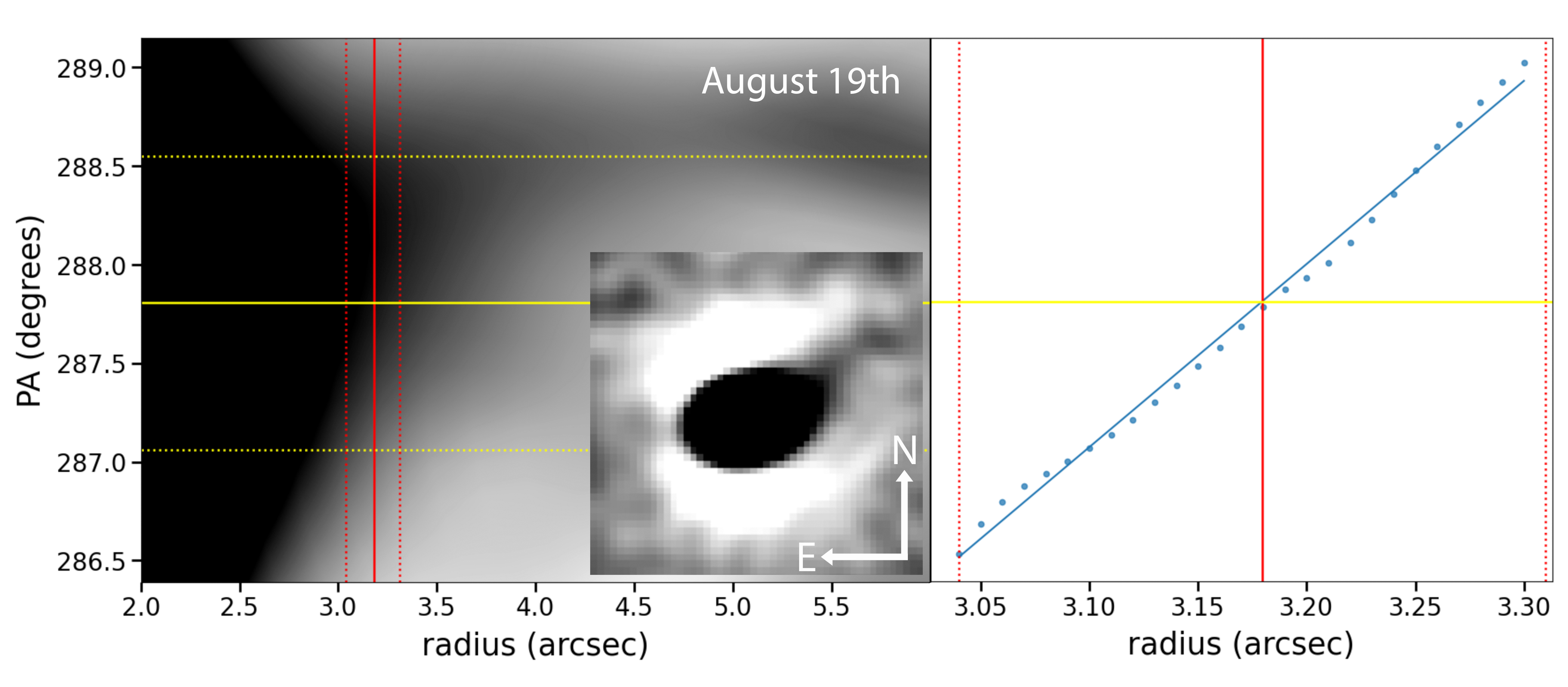

Abstract: We present observations of the detection of a faint high-latitude jet in the inner coma of comet 3I/ATLAS that coincides with the broad plume detected in visible images along PA $280 \pm 10{\circ}$. A detailed analysis shows that the jet was clearly detected on seven nights (2025, August~3, 5, 18, 19, 21, 24, and~29). The jet maintains an almost, though not perfectly, constant position angle (PA) throughout these epochs. High-precision PA measurements at a projected distance of 6000~km from the cometary optocenter reveal a periodic modulation centered at ~ 280 degrees, consistent with a high-latitude jet undergoing precessional motion around the sky-projected spin axis of the nucleus. This is the first periodic jet-angle modulation detected in an interstellar comet. The derived periodicity of $7.74 \pm 0.35$ h may imply a nucleus rotation period of $P_{\mathrm{rot}} = 15.48 \pm 0.70$ h if the jet originates from a single active source near one of the poles. This value is slightly shorter than the period of $P_{\mathrm{rot}} = 16.79 \pm 0.23$ h derived from the photometric time series. From the measured PA range, the sky-projected orientation of the spin axis is derived as $\mathrm{PA} = 280.7 \pm 0.2{\circ}$

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

This paper studies an interstellar comet called 3I/ATLAS before it reached its closest point to the Sun. The researchers spotted a thin “jet” of material shooting out from the comet and noticed that its direction gently wobbled over time. By tracking this wobble, they figured out how fast the comet spins and which way its spin axis points.

What questions did the researchers ask?

- Is there a narrow jet of gas and dust coming from 3I/ATLAS, and does its direction change over time?

- Can the jet’s behavior tell us how the comet’s nucleus (its solid core) is spinning?

- How is the comet’s coma (the fuzzy cloud around it) and tail evolving as it moves toward the Sun?

How did they study the comet?

The team observed 3I/ATLAS on 37 nights from early July to early September 2025 using a 2-meter telescope at the Teide Observatory in Spain. They took many images through a green optical filter and then used image-processing tools to reveal faint structures near the comet’s center.

Key ideas explained simply:

- Coma: The hazy cloud around a comet made of gas and dust released from the nucleus.

- Jet: A narrow “spray” of material from a specific active spot on the comet’s surface—like a tiny nozzle on a rotating sprinkler.

- Pre-perihelion: The time before the comet reaches its closest pass to the Sun.

- Position angle (PA): The direction something points in the sky, measured in degrees like a compass, where 0° is up (north), 90° is right (east), 180° is down (south), and 270° is left (west). A PA near 280° means a bit north of due west.

- Spin axis and wobble: A spinning top doesn’t just spin—it can also slowly wobble. A comet’s jet can show that wobble as a small swing in its pointing direction.

What they actually did:

- They used a Laplacian filter—an “edge-enhancing” technique much like turning up the outlines in a photo—to make faint, thin structures stand out against the bright, smooth coma.

- They measured the jet’s direction at a ring 6,000 km from the bright center of the coma. Think of drawing a circle around the comet and checking where the jet crosses that circle.

- They transformed images into “polar coordinates” (unrolling the circle into a flat graph of angle vs. distance) so a spiral-like jet becomes a near-straight line, making its angle easier to measure precisely.

- To find repeating patterns in the jet’s angle, they used a period-search method (phase dispersion minimization), similar to finding the beat in a song by looking for the most regular rhythm in noisy data.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Main findings:

- A faint, narrow jet was clearly seen on seven nights in August (3, 5, 18, 19, 21, 24, and 29).

- The jet usually pointed around PA ≈ 280° (slightly north of west) and showed a small, regular wobble of about 12° peak-to-peak.

- This wobble repeated every 7.74 ± 0.35 hours. If the jet comes from a single active spot near a pole, that means the nucleus rotation period is about twice that, 15.48 ± 0.70 hours.

- The jet’s average direction reveals the sky-projected spin axis at PA = 280.7 ± 0.2°. That’s a very precise constraint on which way the comet’s “spin pole” points on the sky.

- Earlier and later in the season, the comet’s appearance changed from a mostly sunward fan to a more noticeable antisolar dust tail. The tail stayed short and diffuse, suggesting the dust grains were relatively large and not pushed strongly by sunlight.

- Spectra from other studies show the comet’s activity is likely driven by CO2, which helps lift dust and produce the observed fan and tail.

Why this matters:

- This is the first time a periodic change in a jet’s direction has been detected in an interstellar comet. That’s a big step: it shows that interstellar comets can have localized, “lighthouse-like” activity similar to many Solar System comets.

- By reading the jet’s “swing,” we can learn how the comet spins without needing to see the nucleus directly. That helps us compare the physics of comets from other star systems with those in our own.

What does this mean for the future?

- Understanding spin and jet behavior tells us how outgassing can torque a comet and even change its rotation over time. The slight difference between the jet-based rotation period (~15.5 h) and earlier brightness-based estimates (~16–17 h) might hint at such changes.

- Because 3I/ATLAS comes from another planetary system, learning about its activity and dust helps us understand what comet-like objects are like elsewhere in the galaxy.

- Methods like edge-enhanced imaging and angle tracking offer a practical toolkit for studying future interstellar visitors, letting scientists quickly pin down their spin states and active areas.

- These insights improve models of how comets evolve, how their jets shape their paths, and how materials from other star systems behave when warmed by our Sun.

In short: the team used clever image processing and careful angle measurements to spot a wobbling jet in an interstellar comet. That wobble acted like a telltale clock, revealing the comet’s spin and the direction of its spin axis—opening a new way to read the “body language” of comets from other stars.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following points summarize what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to enable targeted follow-up work:

- Only the sky-projected spin-axis position angle is constrained; the 3D pole orientation (RA/Dec of the pole, obliquity with respect to the orbit plane, and aspect angle) is not solved. A full geometric inversion combining multi-epoch viewing geometries and jet modeling is needed to derive the true pole direction and source latitude.

- The assumption that the jet arises from a single high-latitude source is not tested against alternatives (multiple sources, temporally variable activity, or a broad emission cone). Discriminating among these scenarios requires higher S/N, rotation-phase-resolved imaging and quantitative coma-jet modeling.

- The rotation period inference (PA modulation at 7.74 ± 0.35 h implying 15.48 ± 0.70 h) is based on sparse detections (seven nights) and one period-search method (PDM). A robust period determination demands simultaneous photometry and morphology, multi-method period searches (e.g., Lomb–Scargle, Bayesian, window-function/alias analysis), false-alarm probability quantification, and synodic-to-sidereal corrections.

- Possible spin-state evolution (torques from outgassing) is suggested by discrepancies with earlier photometric periods but not quantified. Constraining torque magnitudes requires time-resolved rotation monitoring across weeks and coupling jet mass flux estimates to spin-up/spin-down models.

- The claim of “precessional motion” is not supported by a dynamical precession model and may reflect simple rotation of a high-latitude source. Testing for actual precession or nutation calls for a longer time baseline and modeling of spin-axis motion.

- The jet PA was measured at a single fiducial radius (~6000 km) without a sensitivity study. The dependence of PA on radius (and its implications for dust/gas speeds and acceleration) is unexplored; radial PA profiles and curvature diagnostics are needed to validate the assumed near-nucleus linearity and Archimedean-spiral behavior.

- Laplacian filtering enhances morphology but does not preserve flux; absolute jet brightness, mass loading, and production rates are unmeasured. Narrowband imaging and spectroscopy (CN, C2, [OI], CO/CO2 bands) are required to quantify gas species and dust mass flux from the jet.

- Potential processing artifacts (background stars, tracking smear, seeing variations, filter-kernel choices) are acknowledged but not systematically mitigated or quantified. A robust pipeline should include non-sidereal tracking, star masking, PSF/seeing compensation, filter parameter sensitivity tests, and validation with simulated comae.

- The extraordinarily small quoted uncertainty on the spin-axis PA (280.7 ± 0.2°) does not include systematic error sources (WCS calibration, camera orientation, geometric distortions, kernel-dependent biases, radius choice). A comprehensive error budget and cross-instrument verification are needed.

- No constraints are derived on jet collimation (opening angle), source latitude, or longitudinal location on the nucleus. Inverting the measured PA amplitude (~12°) with a physical coma model could retrieve source geometry and jet opening angle.

- The volatile driver of the jet (CO vs CO2 vs H2O) is inferred from external studies, not directly from the presented data. Co-temporal spectroscopy and narrowband imaging at the epochs of jet detection are needed to link jet morphology to specific volatiles.

- Non-gravitational accelerations due to anisotropic mass loss are not estimated. Combining jet orientation and mass flux with orbit-dynamics residuals could constrain the magnitude and direction of nongravitational forces.

- Dust properties (size distribution, ejection velocities) are not derived from the authors’ dataset; syndyne–synchrone modeling of the tail and fan, plus co-temporal polarimetry and multi-filter imaging, could quantify grain sizes and speeds consistent with the observed weak radiation-pressure response.

- The observational cadence and coverage (seven clear jet detections across August) are insufficient to sample full rotation cycles continuously or track short-term variability. Multi-site campaigns with continuous coverage and short-exposure, non-sidereal sequences are required to resolve rotation-phase morphology.

- Post-perihelion behavior is unknown; jet persistence, geometry changes, and potential spin-state evolution after perihelion are left unexplored. Extending monitoring across perihelion and into the outbound leg would test the stability of the jet and the rotation period.

- The method assumes uniform rotation with negligible changes in viewing geometry (approximated by PsAMV) without testing sensitivity to small geometric shifts. Incorporating full ephemeris geometry and performing synodic-to-sidereal period correction would reduce systematic bias.

- The Archimedean-spiral assumption for jet projection is stated but not validated against measured curvature or acceleration effects. Measuring PA–radius slopes and curvature, and fitting jet tracks with variable-speed outflow models, would confirm or refute this assumption.

- The analysis is single-band (Sloan g'); color dependence of jet visibility and potential gas contamination (e.g., CN emission in g') are not assessed. Multi-filter imaging (g', r', i', narrowband gas filters) is necessary to separate dust from gas and test wavelength dependence.

- Potential contamination of the Laplacian-detected feature by faint tail streamers or background structures is not ruled out. Star-subtracted stacks, tail-model subtraction, and independent confirmation with alternative enhancement techniques (e.g., Larson–Sekanina, azimuthal median subtraction) are needed.

- Data and code availability for reproducibility are not specified. Public release of calibrated frames, enhancement parameters, PA measurement scripts, and uncertainty propagation would enable independent verification and method intercomparison.

Glossary

- Archimedean spiral: A spiral curve where radius increases linearly with angle; used to model rotating jet projections near the nucleus. "If the jet represents the two-dimensional projection of an Archimedean spiral, the PA-radius relation becomes approximately linear near the nucleus, transforming the jet into a straight feature in the polar frame."

- aspect angle: The angle between the sky-projected spin axis of the comet and the observer’s line of sight. "Assuming that the cometâs aspect angle -- defined as the angle between the sky-projected spin axis and the observerâs line of sight -- remained approximately constant during the observing timespan, we can also constrain the rotation period from the temporal variability of the jet morphology."

- antisolar direction: The direction on the sky opposite to the Sun from the comet’s position. "The projected velocity vector (red arrow) and the antisolar direction (yellow arrow) are marked, as well as the image scale and orientation."

- azimuthal average subtraction: An image-processing technique that removes symmetric coma background by subtracting the azimuthal average. "Image-enhancement techniques such as Laplace \citep{SerraRicart2015Rotation} or LarsonâSekanina filtering \citep{LarsonSekanina1984_HalleyI} and azimuthal average subtraction are commonly used to isolate faint, anisotropic structures from the bright coma background \citep{Boehnhardt1994}."

- back-illuminated CCD sensor: A CCD design with improved quantum efficiency by illuminating the photosensitive layer from the back. "equipped with a back-illuminated 13.5~m pixel BEX2-DD CCD sensor, resulting in a field of view of 7.85\times$7.85$'''^{-1}$."</li> <li><strong>BEX2-DD</strong>: A specific deep-depletion CCD sensor model used for astronomical imaging. "equipped with a back-illuminated 13.5~$\mu^{-1}'7.85 and a plate scale of 0.23~pixel."

- CO sublimation: The phase change of solid carbon dioxide directly to gas, driving cometary outgassing. "with micron-sized dust grains ejected at velocities consistent with gas drag driven by CO sublimation."

- coma: The diffuse atmosphere of gas and dust surrounding a comet’s nucleus. "To enhance the visibility of potential fine-scale structures in the inner coma of 3I/ATLAS, a Laplacian-filtering technique was applied to the reduced and combined images."

- cometary optocenter: The brightness-weighted center of the comet’s image used for alignment and measurements. "High-precision PA measurements at a projected distance of 6000~km from the cometary optocenter reveal a periodic modulation centered at $\sim280\degr$..."

- ephemerides: Tabulated predictions of celestial object positions and related geometry over time. "For practical purposes, this aspect angle is approximated by the angle of the targetâs heliocentric velocity vector (âPsAMVâ in the JPL ephemerides) as projected onto the observerâs plane of the sky."

- gas drag: Momentum transfer from outflowing gas that accelerates and entrains dust grains. "with micron-sized dust grains ejected at velocities consistent with gas drag driven by CO sublimation."

- heliocentric distance: The distance from an object to the Sun. "reveal the onset of activity as a function of heliocentric distance, thereby identifying the dominant volatile species (e.g., CO, CO, and HO) responsible for outflow initiation."

- inversion angle: The phase angle where linear polarization of scattered light changes sign. "Polarimetric measurements reveal an unusually strong negative polarization branch and a low inversion angle, indicating that the coma dust of 3I is dominated by large, compact particles."

- isophotal contours: Curves connecting points of equal brightness in an image. "Isophotal contours of the original (unfiltered) images are overplotted using ten logarithmically spaced levels between the 20th and 95th percentiles of pixel intensity in each frame."

- Laplacian filter: An image-enhancement operator that emphasizes intensity curvature, revealing fine structures. "Unlike azimuthal-average subtraction or the SekaninaâLarson residual technique, the Laplacian filter does not rely on any assumed symmetry of the coma, nor does it require iterative rotational subtraction."

- Laplacian operator: A second-order differential operator highlighting regions of rapid intensity change. "The Laplacian operator highlights spatial curvature, and therefore efficiently suppresses the smooth, steep radial gradient of the coma, while enhancing localized features such as narrow jets or filaments."

- Larson–Sekanina filtering: A comet image-processing technique that enhances radial and rotational features. "Image-enhancement techniques such as Laplace \citep{SerraRicart2015Rotation} or LarsonâSekanina filtering \citep{LarsonSekanina1984_HalleyI} and azimuthal average subtraction are commonly used to isolate faint, anisotropic structures from the bright coma background \citep{Boehnhardt1994}."

- MJD (Modified Julian Date): A continuous count of days used in astronomy, offset from the Julian Date for convenience. "The best-fit solution corresponds to a period of ~h (Fig.~\ref{fig:phase}), with the zero phase defined at MJD~6(0891.1035)."

- Nasmyth 2 focus: A telescope focal configuration located on the altitude axis for instrument mounting. "COLORS, a 2k2k camera mounted at the Nasmyth 2 focus, equipped with a back-illuminated 13.5~m pixel BEX2-DD CCD sensor..."

- negative polarization branch: The range of phase angles where scattered light shows negative linear polarization. "Polarimetric measurements reveal an unusually strong negative polarization branch and a low inversion angle, indicating that the coma dust of 3I is dominated by large, compact particles."

- nongravitational forces: Accelerations on a comet due to outgassing and mass loss rather than gravity. "Their detection provides constraints on the spin-axis orientation, rotation state, and nongravitational forces that drive cometary evolution..."

- nutation: Small periodic wobble superposed on a body’s precession or rotation. "We further assume that the nucleus rotated uniformly throughout the campaign, with no measurable precession or nutation."

- phase dispersion minimization (PDM): A period-search algorithm that minimizes dispersion in folded light curves without assuming sinusoidal signals. "We searched for periodicities in the temporal evolution of the measured PAs using the phase dispersion minimization (PDM) method \citep{Stellingwerf1978PDM}."

- plate scale: The angular size on the sky corresponding to one detector pixel. "resulting in a field of view of 7.85\times$7.85$'''^{-1}$."</li> <li><strong>position angle (PA)</strong>: The angle measured on the sky from north through east to the feature of interest. "The jet maintains an almost, though not perfectly, constant position angle (PA) throughout these epochs."</li> <li><strong>pre-perihelion</strong>: The orbital phase before a comet reaches its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion). "We investigate the pre-perihelion rotational parameters of the nucleus of 3I/ATLAS modeling jet structures observed in the inner coma."</li> <li><strong>precessional motion</strong>: Slow conical rotation of a spin axis around another axis or direction. "consistent with a high-latitude jet undergoing precessional motion around the sky-projected spin axis of the nucleus."</li> <li><strong>PsAMV</strong>: The angle of the target’s heliocentric velocity vector in JPL ephemerides, projected onto the plane of the sky. "For practical purposes, this aspect angle is approximated by the angle of the targetâs heliocentric velocity vector (âPsAMVâ in the JPL ephemerides) as projected onto the observerâs plane of the sky."</li> <li><strong>Ritchey–Chrétien telescope</strong>: A reflecting telescope design with hyperbolic mirrors optimized for wide-field imaging. "TTT3 is a 2.0-m $f$/6 Ritchey-Chrétien telescope that is currently in its commissioning phase."</li> <li><strong>seeing</strong>: Atmospheric blurring of astronomical images, limiting angular resolution. "The detection and analysis of jet features were often hampered by low signal-to-noise ratios, imperfect tracking, confusion with background stars, or poor seeing conditions."</li> <li><strong>sidereal-tracking exposures</strong>: Images taken while tracking the stars’ apparent motion rather than the comet. "For each frame, the observation date (YYYYâMMâDD) and the start and end times in UTC are shown above the panels, together with the total number of sidereal-tracking exposures and the cumulative integration time."</li> <li><strong>sky-projected spin axis</strong>: The orientation of a rotating body’s spin axis as projected onto the plane of the sky. "From the measured PA range, the sky-projected orientation of the spin axis is derived as $\mathrm{PA} = 280.7 \pm 0.2^{\circ}$."</li> <li><strong>Sloan-$g'$ filter</strong>: A specific broadband optical filter from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey system centered in the green. "Jet images were taken using the Sloan-$g'$ filter."

- WCS (world coordinate system): A standardized scheme for mapping image pixels to celestial coordinates. "A WCS (world coordinate system) solution was obtained using Astrometry.net \citep{2010AJ....139.1782L} against Gaia DR2 and all comet images are aligned from the cometâs optocenter."

Practical Applications

Overview

Below are actionable, real-world applications that follow from the paper’s findings (periodic, pre-perihelion jet-angle modulation in 3I/ATLAS; spin-axis orientation; rotation-period constraints), methods (Laplacian filtering, polar-coordinate transformation, parabolic fitting for jet PA, phase-dispersion minimization), and innovations (a robust, symmetry-agnostic workflow to detect and track faint inner-coma jets). Applications are grouped as immediate (deployable now) and long-term (requiring further development, scaling, or validation). Each item includes sector links and notes on key assumptions or dependencies that affect feasibility.

Immediate Applications

These items can be implemented with current tools, data, and practices.

- Academia (Astronomy) — Jet-based rotational characterization workflow

- Use the Laplacian-filter + polar transform + PA fitting pipeline to derive rotation periods and sky-projected spin-axis orientations of comets and active asteroids from small/medium-aperture telescopes.

- Potential tools/workflows: “Jet-PA Tracker” module (Python/Astropy/AstroImageJ plugin) that standardizes WCS alignment, Laplacian filtering, polar remapping, parabolic fitting at fixed radii, and PDM period search.

- Sector: Research/education; small observatories.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate WCS; sufficient S/N; jet approximates a near-nucleus spiral; viewing geometry changes are small over the campaign; single high-latitude source (or well-characterized multi-source models).

- Space-based and Ground-based Scheduling — Rotation-aware observation planning

- Time spectroscopy/polarimetry/photometry to the jet’s rotational phase (e.g., schedule JWST/VLT/HST or high-cadence ground observations to sample active-source visibility).

- Sector: Space operations, observatory scheduling software.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Rotation period stability within the scheduling window; availability of phase zero (epoch) and current ephemerides; minor evolution of outgassing torques.

- Orbit determination practice — Incorporate anisotropic activity awareness

- Flag interstellar/comet orbit fits where non-gravitational terms (A1/A2/A3) may be influenced by persistent jets; use morphology-derived spin-axis constraints to inform force models and residual interpretation.

- Sector: Planetary defense, celestial mechanics, astrodynamics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quantitative coupling between jet orientation/strength and non-gravitational accelerations is needed; current paper provides orientations and periods, not torque magnitudes.

- Observatory operations — Robust jet detection in low S/N data

- Adopt Laplacian filtering for inner-coma structure detection when azimuthal symmetry assumptions fail or seeing/tracking are imperfect; train staff on confusion mitigation (background stars, tracking errors).

- Sector: Observatory pipelines, commissioning/QA.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Proper calibration (bias/dark/flat), seeing control, and careful star-masking; awareness that Laplacian filtering does not preserve absolute flux (morphology only).

- Software/Imaging industry — Filament detection toolkit for low-contrast scenes

- Repurpose the Laplacian + polar-linearization paradigm to detect narrow, faint, filamentary features in noisy images (e.g., hairline cracks, fibers, micro-scratches) in manufacturing QC.

- Sector: Software, machine vision, quality assurance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain-specific tuning of filter kernels and polar mapping steps; validation datasets; integration with existing vision stacks.

- Time-series analytics — PDM for uneven sampling

- Use phase-dispersion minimization to analyze periodicity in irregularly sampled industrial sensor data (e.g., predictive maintenance logs, environmental monitoring, network telemetry).

- Sector: Software/data analytics; industrial IoT.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Appropriate detrending and error modeling; cautious interpretation when amplitudes are small or multiple harmonics exist.

- Education/Citizen science — Comet jet detection modules

- Create hands-on labs and citizen-science workflows that teach WCS alignment, Laplacian-enhancement, and PA measurements from public comet images, connecting morphology to spin-state inference.

- Sector: Education, outreach.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to public datasets; easy-to-use open-source tooling; guidance on pitfalls (e.g., star trails, seeing variability).

Long-Term Applications

These items need further research, scaling, or integration before broad deployment.

- Mission design for interstellar comet encounters

- Use morphology-constrained spin axis and rotation period to design safe sampling trajectories, illumination-aware approach profiles, and instrument pointing that favors active-source capture.

- Sector: Space mission architecture, guidance/navigation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Confirmed jet locations on the nucleus; evolution of rotation with outgassing torques; spacecraft availability and timeline.

- Torque-aware orbit and spin evolution models

- Build physics-based models linking measured jet geometry and periodicity to non-gravitational accelerations and spin-up/down rates; integrate into orbit determination software for interstellar objects.

- Sector: Astrodynamics, planetary defense policy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quantitative jet mass flux and velocity fields; multi-epoch torque measurements; cross-validation with photometric/thermal models.

- 3D jet tomography from multi-instrument data

- Fuse Laplacian-enhanced imaging with spectroscopic cubes (e.g., VLT/MUSE) and polarimetry to reconstruct active-source latitude/longitude, opening angles, and grain-size distribution in 3D.

- Potential product: “ComaMorph-3D” reconstruction toolkit.

- Sector: Research software, instrumentation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Coordinated multi-wavelength datasets; well-characterized PSFs; forward models for dust/gas dynamics.

- Autonomous observatories with edge analytics

- Develop real-time pipelines (at the telescope) that detect jet presence and phase, dynamically re-prioritize observations, and trigger multi-site follow-up when activity changes.

- Sector: Robotics/autonomy; cloud-edge compute.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable on-site compute; standardized APIs for scheduling; latency-tolerant coordination among observatories.

- Standards and protocols for interstellar object follow-up

- Establish policy/consensus on rapid global coordination, data formats, and minimum characterization sets (spin axis, rotation period, jet presence) to enhance scientific return and hazard assessment.

- Sector: Policy, international consortia (IAU, NASA, ESA).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Governance mechanisms; funding and sustained participation; interoperability across facilities.

- Comparative cometology databases

- Systematically archive jet morphology, PA modulations, spin states, and volatile compositions across Solar System and interstellar comets to quantify diversity and origins.

- Sector: Research infrastructure, data platforms.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Uniform methodologies; metadata standards; long-term curation and access.

- Cross-domain imaging R&D

- Adapt the spiral-linearization approach (polar transform of near-spiral features) to biomedical imaging (e.g., vascular spirals, ciliary motion), microfluidics (helical flows), or geospatial plume analysis.

- Sector: Healthcare imaging; environmental sensing; advanced manufacturing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain-specific physics and sampling; annotated training data; regulatory considerations in healthcare.

- ML-ready comet morphology datasets

- Curate labeled inner-coma images and jet PA time series to train models that automatically detect and classify jet types, predict rotation, and flag non-gravitational effects.

- Sector: AI for science; software products.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sufficiently large, high-quality datasets; consensus on labels; open benchmarks.

- Public STEM curricula aligned with next-generation surveys

- Build LSST-era coursework and hackathons that teach low-surface-brightness processing, jet detection, and spin inference, preparing students for data volumes and methods.

- Sector: Education policy and program development.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to LSST-like data; teacher training; sustainable funding.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.