Operational Derivation of Born's Rule from Causal Consistency in Generalized Probabilistic Theories

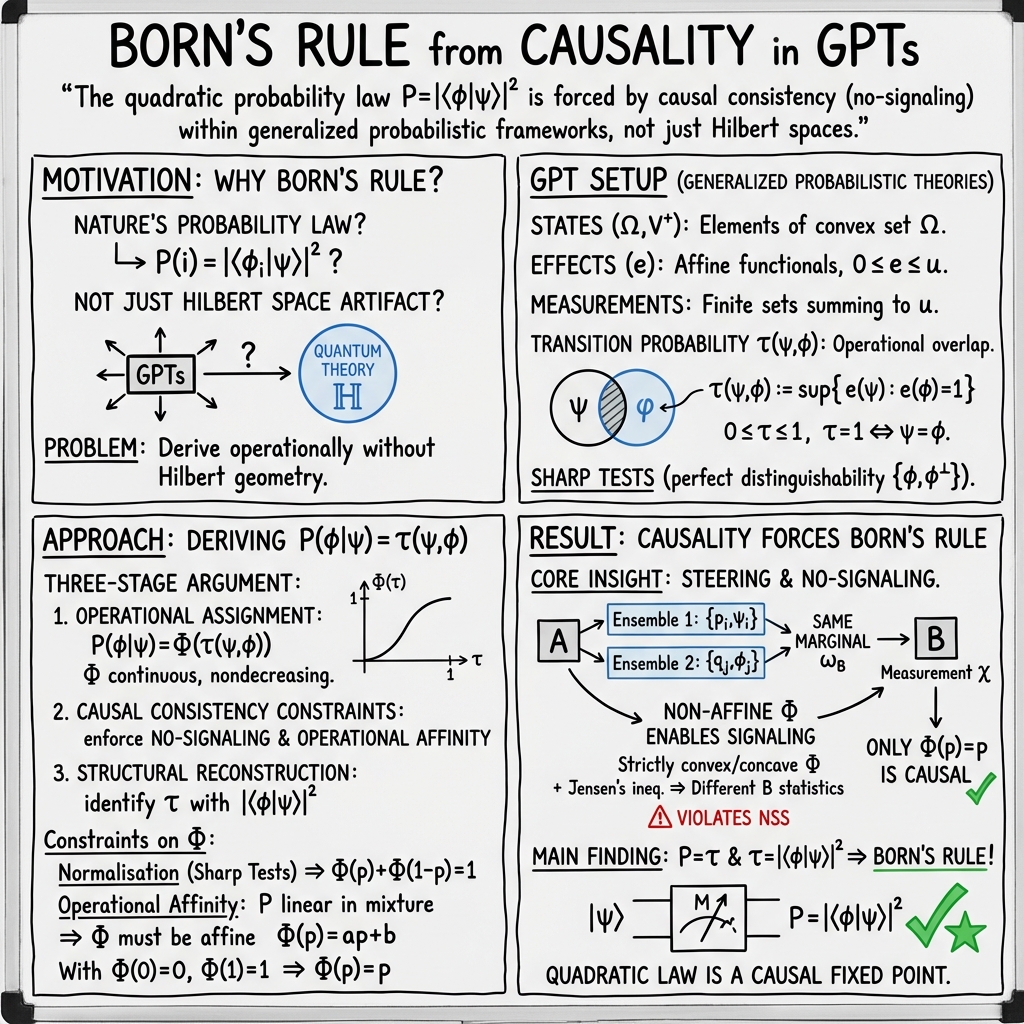

Abstract: We present an operational derivation of Born's rule within finite-dimensional generalized probabilistic theories (GPTs), without assuming Hilbert-space structure. From a single causal requirement, namely causal consistency, together with sharp measurements, reversible symmetries, and no-signaling, we show that any admissible state-to-probability map must be affine under mixing; otherwise, its curvature enables superluminal signaling via steering. Using standard reconstruction results, affinity forces the probability assignment to coincide with the quadratic transition function of complex quantum theory. Our three-stage argument (operational assignment, causal-consistency constraints, and structural reconstruction) recovers complex quantum theory and identifies Born's rule as a causal fixed point among admissible probabilistic laws. We discuss limitations of the derivation and outline steering-based experiments that could bound deviations from affinity.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Simple Overview

This paper tries to explain why the famous “Born’s rule” in quantum physics has the exact form it does. Born’s rule is the recipe that turns the “overlap” between a quantum state and a measurement outcome into a probability. In ordinary quantum theory, that probability is the square of the overlap, written as . Instead of assuming the usual math of quantum theory from the start, the paper asks: if we only require that physics doesn’t allow faster-than-light signaling and behaves sensibly when we mix states, does Born’s rule follow automatically? The answer they give is yes.

What Questions Did the Paper Ask?

Here are the main questions, phrased simply:

- If we work in a very broad framework that includes classical physics, quantum physics, and other possible theories, what should the rule be for turning “how much two states overlap” into a probability?

- What basic, physical requirements (like “no faster-than-light messages”) force that rule to be the same as Born’s rule?

- If we accept those requirements, can we rebuild (reconstruct) ordinary quantum theory from them?

How Did They Try to Answer? (Methods in Simple Terms)

The authors use a general “playground” for physical theories called Generalized Probabilistic Theories (GPTs). Think of GPTs as a big toolkit where:

- States are like points in a shape, and mixing states is like averaging points (like mixing paints).

- Measurements are like tests you run on a state to get a yes/no or multiple-choice answer, with certain probabilities.

- The framework is designed to include classical and quantum theories, plus other hypothetical ones, in a single language.

They focus on three steps:

- Operational assignment (what probabilities do we assign?)

- They define an “operational transition probability” between two pure states and . In everyday terms, imagine a perfect test that always says “yes” for . Then is the highest chance that this same test also says “yes” if the true state is . In standard quantum theory, equals , but here they don’t assume that yet.

- They allow the actual probability you report, , to be any reasonable function of this overlap: . Here is just some curve from 0 to 1 that starts at 0 and ends at 1.

- Causal-consistency constraints (what’s physically allowed?)

- No faster-than-light signaling: Your choice of measurement here shouldn’t instantly change what someone far away sees.

- Affinity (linearity under mixing): If you flip a coin to prepare state A or B, the final probability should be the average of the probabilities for A and for B. This is just “probabilities average when you average preparations.”

- Steering: In quantum-like theories with entanglement, one person (Alice) can choose different ways to “split” the same average state for someone else (Bob) at a distance. Even though Bob’s average state is the same, the detailed “recipe” (the ensemble) can differ depending on Alice’s choice.

Here’s the key idea: if the curve is not a straight line (not affine), then different “splits” (ensembles) of the same average lead to different averaged probabilities after you pass them through the curved function . That would let Alice change Bob’s observed statistics from far away—meaning faster-than-light signaling—which is not allowed. To prevent that, must be a straight line. With the boundary points fixed ( and ), the only straight line is . So the probability rule must be:

- Structural reconstruction (what theory does this give us?)

- The authors then use known results: if your theory satisfies some standard, reasonable axioms (like “you can fully describe a whole system from local measurements,” “mixed states can come from part of a bigger pure state” (purification), “you can smoothly transform any pure state into any other,” and “there are sharp, perfect tests”), then your theory turns out to be ordinary complex quantum theory. In that case, . Since they already showed , they recover Born’s rule.

To keep the technical terms grounded, here are the main axioms in everyday language:

- No signaling: No sending messages faster than light.

- Local tomography: You can figure out the whole by measuring the parts.

- Purification: Any “mixed” state can be seen as part of a larger “pure” state (like being a slice of a bigger, cleaner picture).

- Continuous reversibility: You can smoothly transform any pure state into any other without losing information.

- Sharpness/spectrality: There exist perfect yes/no tests that cleanly separate certain states.

- Strong symmetry: All “classical-looking” bases are treated the same by the allowed transformations.

What Did They Find and Why Is It Important?

Main findings:

- If you demand no faster-than-light signaling and that probabilities average sensibly when you mix states, then the probability rule must be ; in other words, the function has to be the identity (a straight line).

- Using standard reconstruction results, this leads directly to ordinary quantum theory, where . That is exactly Born’s rule.

- Any curved (nonlinear) modification of the rule would allow signaling when combined with steering, which breaks causality.

Why this matters:

- It shows Born’s rule isn’t just a quirky detail of Hilbert spaces; it’s the only rule that keeps probabilities compatible with relativity (no faster-than-light communication) in a very broad class of theories.

- It makes the rule feel necessary and robust, not arbitrary.

Why It Matters (Implications)

- Causality as a guide: The familiar quantum probability rule emerges directly from the simple demand that physics respect cause-and-effect across space (no instant messaging).

- Uniqueness: Among many imaginable ways to turn “overlap” into probabilities, only the Born rule survives these basic constraints.

- Testability: The authors outline how experiments using entanglement and steering could look for tiny deviations from the straight-line rule. If any were found, it would have huge implications (it would hint at new physics and possible signaling).

Limits and Next Steps

- The current proof works for finite-dimensional systems (think small, countable settings), not for infinite-dimensional systems like fields. Extending it to those would need more math.

- It assumes a set of strong but standard axioms (like purification and strong symmetry). Future work might try to weaken these assumptions.

- The paper suggests steering-based experiments that could set bounds on any possible deviations from the straight-line probability rule, making the idea falsifiable in principle.

Bottom Line

By insisting on two simple, physical ideas—no faster-than-light signaling and “probabilities average when you average preparations”—the paper shows that the only consistent probability rule in a very general framework is exactly the quantum Born rule. This connects the heart of quantum randomness to the basic structure of cause and effect in our universe.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.