A Geometric Theory of Cognition (2512.12225v1)

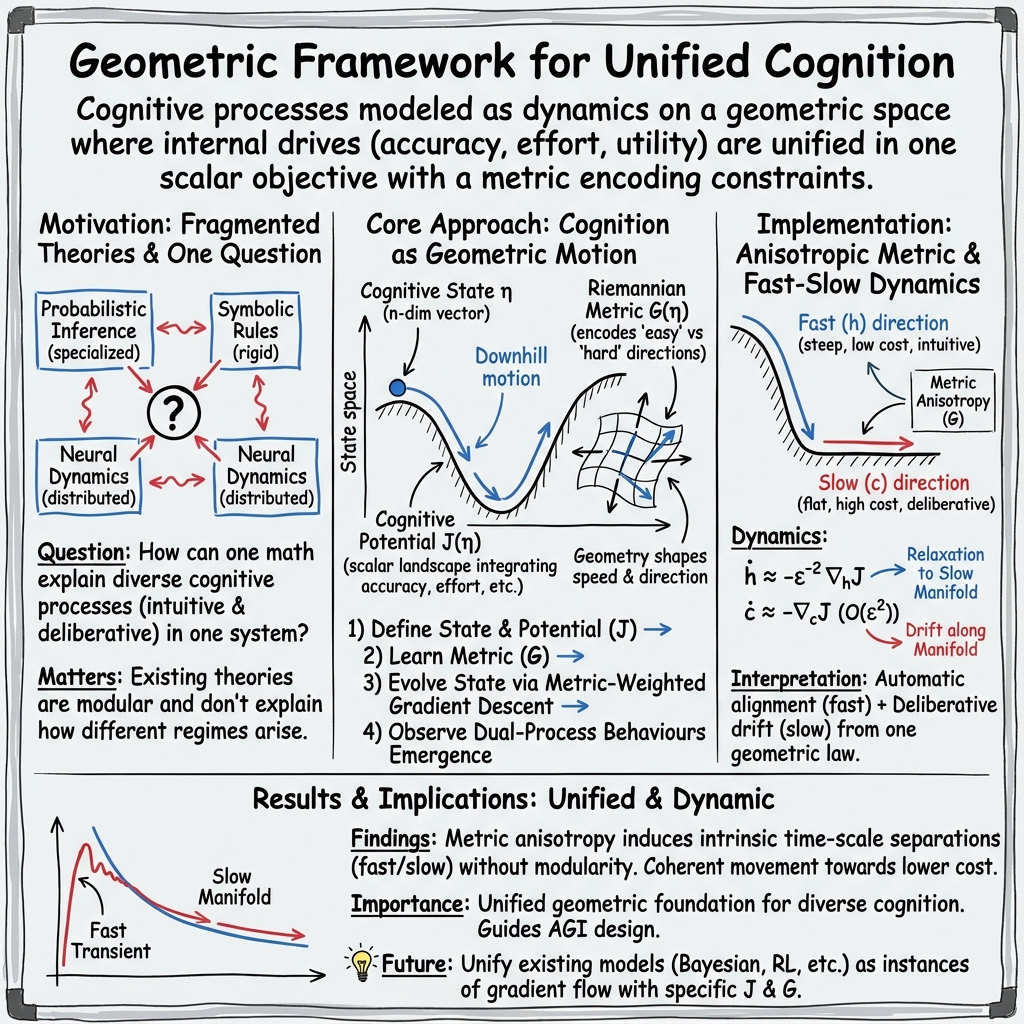

Abstract: Human cognition spans perception, memory, intuitive judgment, deliberative reasoning, action selection, and social inference, yet these capacities are often explained through distinct computational theories. Here we present a unified mathematical framework in which diverse cognitive processes emerge from a single geometric principle. We represent the cognitive state as a point on a differentiable manifold endowed with a learned Riemannian metric that encodes representational constraints, computational costs, and structural relations among cognitive variables. A scalar cognitive potential combines predictive accuracy, structural parsimony, task utility, and normative or logical requirements. Cognition unfolds as the Riemannian gradient flow of this potential, providing a universal dynamical law from which a broad range of psychological phenomena arise. Classical dual-process effects--rapid intuitive responses and slower deliberative reasoning--emerge naturally from metric-induced anisotropies that generate intrinsic time-scale separations and geometric phase transitions, without invoking modular or hybrid architectures. We derive analytical conditions for these regimes and demonstrate their behavioural signatures through simulations of canonical cognitive tasks. Together, these results establish a geometric foundation for cognition and suggest guiding principles for the development of more general and human-like artificial intelligence systems.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper tries to answer a big question: can we describe how thinking works — from quick gut reactions to slow careful reasoning — with one simple math idea? The author proposes a geometric way to model the mind. Imagine your mind’s “state” as a point moving on a smooth landscape. That landscape has:

- a shape that tells you which directions are easy or hard to move in (the “metric”), and

- a height that tells you how good a state is (the “cognitive potential”).

Thinking, in this view, is like a ball rolling downhill on this landscape toward better, more consistent, and more useful states.

Key Questions

To make this idea clear, the paper asks a few straightforward questions:

- Can we represent all kinds of thinking (perception, memory, action, reasoning) in one model?

- Why do we have both fast, automatic reactions and slow, deliberate reasoning?

- Can these two modes of thought come from the same underlying rule, without building separate systems?

Methods and Approach

The paper builds a simple mathematical model of cognition using everyday analogies:

- The mind’s state is like a location on a smooth map (a “manifold”). Each coordinate (like a street and an avenue) represents parts of cognition (for example, habits vs. beliefs).

- The “metric” is like the terrain or friction on that map. In some directions you can move easily (low effort), and in others it’s hard (high effort). This captures that some mental changes (like adjusting a habit) can be quicker than others (like changing a deep belief).

- The “cognitive potential,” written as , is like the height of a landscape. Lower places are better — they mean more accurate predictions, simpler representations, higher task success, more logical consistency, and lower mental effort. The potential combines all these pressures into one score.

- “Gradient flow” is the rule for movement: the mind’s state slides downhill in the steepest direction, but the steepness depends on the metric (the terrain). This ensures the system always moves toward states with lower cost and stops at good resting points.

A key setup in the model splits the mind’s state into two parts:

- : fast, automatic parts (habits, reflex-like adjustments),

- : slow, deliberate parts (beliefs, goals, careful reasoning).

By setting the metric so that moving in is easy and moving in is hard, the system naturally produces fast changes in and slow changes in — just like fast intuition and slow deliberation.

The paper also provides a step-by-step mathematical proof (using standard “fast–slow systems” theory) that:

- the fast part quickly settles into a stable configuration given the slow part,

- there’s a “slow manifold” — a stable valley where the system stays most of the time,

- the slow part then drifts along this valley, changing gradually.

Main Findings

Here are the main results, explained simply:

- One rule explains many kinds of thinking: The “roll downhill” rule on a shaped landscape can cover perception, memory, action selection, and reasoning — because the potential can include all the important pressures at once (accuracy, simplicity, reward, logic, effort).

- Fast and slow thinking emerge automatically: You don’t need to build two separate minds. If the landscape is steep in some directions (cheap/easy to change) and flat in others (costly/hard to change), fast and slow behavior appear on their own.

- Always moving toward better states: Because the system follows the downhill rule, the overall “cognitive potential” never increases. In everyday terms, thinking keeps reducing errors, conflicts, and wasted effort.

- Stable habits, flexible reasoning: The fast part () rapidly locks into an “automatic” pattern that fits the current context (set by ). If a sudden bump pushes off track, it quickly snaps back. Meanwhile, the slow part () keeps integrating information and adjusting over time.

- Realistic decision behavior: In simulations, the system shows:

- quick automatic alignment,

- slow drifting as evidence accumulates,

- sudden switches when the landscape changes enough (like a tipping point in a decision),

- immediate re-alignment of automatic processes after the switch.

The paper demonstrates these results with simple two-dimensional examples. For instance, using a tiny parameter to make changes costly slows down by about a factor of hhcc$ moves slowly along it. The reduced model (that only follows the slow manifold) closely matches the full system after the fast part settles.

Why It’s Important

- Unified view: This approach brings together different theories — like Bayesian reasoning, reinforcement learning, predictive coding, and dual-process psychology — by showing they can be seen as special cases of moving downhill on a shaped landscape.

- Explains dual-process thinking: It shows why quick intuition and slow reasoning both happen within one system — because some directions are cheaper and steeper than others, not because the mind is split into separate modules.

- Predicts behavior: It suggests testable patterns in response times, learning curves, and decision switching based on the geometry (shape) of the cognitive landscape.

Implications and Potential Impact

- For cognitive science: This geometric framework can connect ideas across psychology, neuroscience, and computation. It makes clear predictions about how effort, working memory, and attention relate to the “shape” of mental space.

- For artificial intelligence: It offers a way to design AI systems that think more like humans — using a single internal state updated by one rule, handling both fast reactive behaviors and slow planning without separate modules. Many modern AI ideas (like world models and self-supervised learning) can fit into this framework.

- For stability and interpretability: The geometric setup ensures smoother changes, clearer convergence, and structured long-term behavior, which could help build AI that’s more reliable and aligned with goals.

Simple Takeaway

Imagine thinking as moving a ball across a landscape that encodes everything the mind cares about — accuracy, simplicity, goals, rules, and effort. The terrain’s shape decides which changes are easy or hard. The ball rolls quickly down steep slopes (fast, automatic responses) and slowly across flat areas (deliberate reasoning). This single idea can unify many separate theories of mind and guide the design of smarter, more human-like AI systems.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, stated concretely so future researchers can act on them.

- Empirical validation: No quantitative tests against human behavioral datasets (e.g., response-time distributions, speed–accuracy trade-offs, dual-process switches); design and run experiments to fit and compare the model to canonical tasks.

- Latent-state identification: The mapping from observable behavior/neural signals to latent cognitive coordinates η and their dimensionality n is unspecified; develop inference procedures (e.g., state-space modeling) with identifiability guarantees.

- Learning the geometry and potential: No method is provided to learn the Riemannian metric G(η) and cognitive potential J(η) from data; propose estimation algorithms, regularizers, and sample-complexity analyses for jointly learning G and J.

- Metric semantics: The relation between G and known information-geometric structures (e.g., Fisher information/natural gradient) is left vague; specify conditions under which G coincides with or extends these metrics and how to estimate it empirically.

- Component design of J: The paper lists J as a sum of prediction, complexity, reward, norms, and effort terms but does not define concrete functional forms or weighting schemes; derive principled formulations and learning rules for combining these components.

- Nonautonomous dynamics: Results assume time-independent J, yet simulations use time-varying J(h,c,t); extend monotonicity, slow-manifold existence, and reduction theory to nonautonomous gradient flows with changing landscapes.

- Stochasticity and noise: Cognition is modeled deterministically; incorporate stochastic gradient/Langevin terms and analyze metastability, variability in RTs, and noise-driven switching with formal bounds and empirical tests.

- Multiple fast equilibria: Assumption (J2) imposes a unique fast minimizer h*(c); generalize the theory to cases with multiple fast attractors (habit sets), including bifurcations, mode competition, and hysteresis in h.

- Off-diagonal metric structure: Analyses rely on a block-diagonal Gε; characterize fast–slow behavior with full, state-dependent metrics (including cross-couplings), and study canards, mixed-mode dynamics, and robustness of slow manifolds.

- Origin and adaptivity of ε: The small parameter ε is posited but not derived; link ε (or anisotropy in G) to measurable resource constraints (e.g., working-memory load, attention) and devise mechanisms for task-dependent adaptive ε/G.

- Escape from local minima: Pure gradient flow cannot leave suboptimal basins without time-varying changes; formalize mechanisms (noise, annealing, control inputs, meta-optimization of J/G) enabling exploration and reassessment.

- Global convergence and stability: Provide conditions beyond local convexity ensuring global convergence, basin stability, and guarantees against pathological traps in high-dimensional non-convex J.

- Scalability: Demonstrations are 2D toy problems; assess computational tractability, stiffness, and numerical stability for high-dimensional η with realistic task complexity and report performance benchmarks.

- Comparative evaluation: No quantitative comparison to established models (drift–diffusion, predictive coding, free-energy, RL); implement baselines and show where the geometric flow predicts differences and wins/loses empirically.

- Neurobiological mapping: Specify how η and G/J correspond to neural circuits, neuromodulators, and measured timescales; derive testable neurophysiological predictions (e.g., curvature correlates with cognitive effort or PFC activity).

- Memory processes: The framework claims generality but does not model episodic/semantic memory encoding, retrieval, consolidation, or forgetting; propose J/G designs capturing memory dynamics and validate on memory tasks.

- Social inference and multi-agent cognition: Extensions to social reasoning are asserted but not analyzed; define joint manifolds, interaction metrics, and potentials for multi-agent settings, and study equilibrium/learning in social tasks.

- Symbolic and discrete constraints: Logical/normative requirements are treated as smooth penalties; develop methods for nonsmooth or discrete constraints (e.g., subgradient/proximal flows, projected manifolds) and prove convergence.

- Alignment and safety: Encoding “norms” within J is proposed but unspecified; provide concrete constructions for normative constraints, conflict resolution among J components, and formal guarantees (e.g., invariants, barrier certificates).

- Observation and prediction errors: The generative/observation model linking the world to prediction penalties is not formalized; define probabilistic observation models and derive the corresponding terms in J with estimation procedures.

- Response-time theory: Despite claims of trajectory-level predictions, no analytical derivations of RT distributions or speed–accuracy curves are provided; derive and test closed-form predictions under stochastic or time-varying J/G.

- Parameter estimation and regularization: There is no guidance on regularizing G(η) to remain symmetric positive-definite during learning or avoiding overfitting in J; propose constraints, priors, and optimization protocols.

- Manifold rigor: The theory asserts a manifold but works in ℝn with coordinate metrics; ensure coordinate invariance (charts, pullbacks) and show results hold under reparameterizations and true manifold embeddings.

- Curvature estimation: The role of curvature in effort/time-scale separation is hypothesized but not operationalized; develop methods to estimate local curvature from behavioral trajectories and relate it to measurable effort.

- Oscillations and rhythms: Monotonic J precludes sustained oscillations, yet cognition exhibits rhythmic/oscillatory dynamics; extend the framework (e.g., with inertial/Hamiltonian terms or non-gradient components) and analyze stability.

- Constraints and projections: Real tasks include hard constraints (e.g., capacity limits); integrate inequality/equality constraints via projected Riemannian flows and study feasibility and convergence.

- Robustness analysis: Provide sensitivity analyses (to noise, parameter drift, task perturbations) and derive Lipschitz/basin-stability bounds for the coupled G–J dynamics.

- Adaptive control of geometry: Formalize meta-control that modifies G in real time based on task demands (attention shifts), with learnable policies and guarantees on stability/performance.

- Causal interventions: Develop methods to distinguish effects of intervening on J vs. G (do-calculus-style), enabling causal testing and model falsification in experiments.

- Implementation and benchmarks: The released code demonstrates toy flows only; create open benchmarks, scalable implementations, and reproducible pipelines that learn J/G and test across diverse cognitive tasks and environments.

Glossary

- Anisotropic metric: A Riemannian metric that weights different directions unequally, inducing variable costs and speeds of change across coordinates. "when the system evolves under the anisotropic metric "

- Anisotropy: Direction-dependent variation in geometric or dynamical properties that affects how the system evolves. "metric-induced anisotropies that generate intrinsic time-scale separations and geometric phase transitions"

- Attractor: A state or set toward which dynamics converge under the flow. "fast, attractor-driven dynamics characteristic of intuitive or habitual responses"

- Block-diagonal metric: A metric matrix composed of independent diagonal blocks, used to decouple fast and slow coordinates by assigning different costs. "we equip the cognitive manifold with a block-diagonal metric that assigns different costs to motion in different directions."

- Critical manifold: The set of equilibrium points of the fast subsystem, typically defined by zeroing a subset of gradients. "Define the critical manifold "

- Differentiable manifold: A smooth geometric space locally resembling Euclidean space where calculus can be performed. "We represent the internal cognitive state as a point on a differentiable manifold"

- Dual-process theories: Psychological models positing coexisting fast intuitive and slow deliberative systems of thought. "Dual-process theories describe the coexistence of fast and slow modes of thought"

- Eigenvalue: A scalar characterizing the action of a linear operator along certain directions, used for stability analysis. "denotes the smallest eigenvalue of the Hessian matrix"

- Energy landscape: A surface mapping states to potential values, whose shape guides dynamical descent. "Energy landscape for the two-dimensional illustrative system"

- Exponential stability: Convergence to an equilibrium at a rate proportional to an exponential function of time. "has a unique exponentially stable equilibrium "

- Fenichel’s persistence theorem: A result ensuring that normally hyperbolic invariant manifolds persist under small perturbations. "apply Fenichel’s persistence theorem"

- Fast–slow decomposition: A partition of system variables into fast and slow components to analyze multi-timescale dynamics. "the fast--slow decomposition used to model intuitive versus deliberative cognition"

- Free-energy principle: A theoretical framework modeling cognition as minimizing variational free energy to explain perception and action. "the free-energy principle"

- Geometric phase transitions: Abrupt qualitative changes in dynamics driven by the geometry of the state space and potential. "geometric phase transitions"

- Geometric singular perturbation theory: Methods for analyzing systems with multiple timescales via invariant manifolds and normal hyperbolicity. "classical geometric singular perturbation theory"

- Hessian: The matrix of second derivatives of a function, encoding local curvature used in stability and curvature analyses. "the Hessian exist and vary smoothly"

- Invariant manifold: A subset of the state space that trajectories do not leave once on it, structuring the system’s dynamics. "admits a locally invariant manifold"

- Jacobian: The matrix of first derivatives that linearizes a vector field around a point, used to assess local dynamics. "On , the Jacobian in the -direction is"

- Normal hyperbolicity: A property where contraction/expansion transverse to a manifold dominates tangential dynamics, ensuring persistence under perturbation. "Hence is a normally hyperbolic attracting manifold"

- Positive-definite matrix: A symmetric matrix with strictly positive quadratic form, defining valid inner products and metrics. "a symmetric, positive-definite matrix whose entries encode the local geometric structure of the cognitive manifold."

- Riemannian gradient: The gradient defined with respect to a Riemannian metric, giving the direction of steepest ascent under that geometry. "The Riemannian gradient is the unique vector field satisfying"

- Riemannian gradient flow: Dynamics that follow steepest descent relative to a Riemannian metric on the manifold. "The Riemannian gradient flow of the cognitive potential with respect to this metric is defined by"

- Riemannian metric: A smoothly varying inner product on the tangent spaces of a manifold, encoding geometry and costs. "endowed with a learned Riemannian metric that encodes representational constraints"

- Singular perturbation methods: Analytical techniques for systems with small parameters that create multiple timescales, enabling reduced models. "using singular perturbation methods (Tikhonov and Fenichel theory)"

- Singular-perturbation limit: The limiting regime as the small parameter goes to zero, revealing fast equilibria and reduced dynamics. "absorbed into the effective slow dynamics in the singular-perturbation limit."

- Slow manifold: The manifold of quasi-equilibria to which fast variables rapidly converge, along which slow variables evolve. "slow manifold "

- Strong convexity: A curvature condition on a function ensuring a unique minimizer and robust stability. "ensures strong convexity and exponential stability of the fast equilibrium."

- Time-scale separation: A phenomenon where different components evolve at distinct characteristic speeds. "intrinsic time-scale separations"

- Tikhonov and Fenichel theory: Classical framework combining Tikhonov’s singular perturbation results with Fenichel’s invariant manifold theory. "singular perturbation methods (Tikhonov and Fenichel theory)"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following list outlines specific, deployable use cases that can be built now by instantiating a cognitive potential J and a (possibly anisotropic) Riemannian metric G, then running the Riemannian gradient flow to orchestrate fast intuitive updates and slower deliberative adjustments.

- Cognitive task modeling and experiment analysis in psychology and neuroscience

- Sectors: academia (cognitive science, neuroscience), healthcare (clinical psych)

- Use case: Fit response-time distributions, switching thresholds, and dual-process signatures (fast intuitive vs slow deliberative) in tasks (e.g., two-choice decisions, evidence accumulation) using the provided gradient-flow model and code.

- Tools/workflows: Use the GitHub code to simulate tasks; estimate parameters for J components (prediction error, effort) and block-anisotropic G; fit to behavioral datasets; run model comparison against alternative theories.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires mapping observed behaviors to a latent state η; smooth J and identifiable parameterization; sufficient data to learn/validate G and J.

- Dual-process decision support for clinical triage and diagnostics

- Sectors: healthcare (emergency, primary care), software

- Use case: A triage assistant that issues immediate heuristic recommendations (fast flow along high-curvature directions) and concurrently builds a slower, evidence-integrating diagnostic suggestion; triggers “phase transition” alerts when the deliberative state crosses a decision threshold.

- Tools/products: “Dual-Process Triage Copilot” leveraging a cognitive potential J with J_norms (guidelines), J_reward (utility), and J_effort (resource costs); “PhaseSwitch Monitor” to detect basin crossings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clinical validation and governance; robust encoding of clinical norms into J; telemetry for evidence updates; interpretable thresholds for handoff from fast to slow modes.

- Resource-aware inference scheduling in machine learning systems

- Sectors: software/ML, edge computing

- Use case: Dynamically allocate compute across model subsystems by encoding compute/attention costs in G and effort penalties in J; run fast paths for routine queries and slow paths when uncertainty or constraints suggest deeper reasoning.

- Tools/products: “Riemannian Inference Scheduler” (block-diagonal G with cheap vs expensive subsystems), integration with existing natural-gradient or preconditioned optimizers, budget-aware serving.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Latent η and subsystem decomposition; differentiable pipelines; monitoring uncertainty/calibration; cost models for effort components.

- Unified reflex–planner controllers for robotics

- Sectors: robotics, manufacturing

- Use case: Controllers that combine fast reflexive stabilization (h-coordinates) and slower goal/legal constraints (c-coordinates) in a single flow; quick realignment after environment changes; smooth convergence enforced by the geometry.

- Tools/products: “Gradient-Flow Controller” with anisotropic G and potential terms for safety, energy, task reward; “Slow-Manifold Tracker” to keep operation near the learned slow manifold.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable identification of fast vs slow control variables; safety certification; runtime estimation of gradients; domain adaptation across tasks.

- Adaptive tutoring that accounts for cognitive effort and habit formation

- Sectors: education, edtech

- Use case: Deliver quick practice (fast updates) while gradually reshaping conceptual understanding (slow updates), using J_effort to prevent overload and J_complexity to control curriculum complexity.

- Tools/products: “Effort-Aware Tutor” with metric anisotropy per skill; lesson sequencing via reduced slow dynamics; dashboards that visualize learner progress along the slow manifold.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Valid learning analytics to infer η; careful design of J components; privacy and data protection; ongoing A/B testing.

- Human–computer interaction that adapts UI behavior to cognitive geometry

- Sectors: software, productivity

- Use case: Interfaces surface immediate, low-effort options while deferring complex reconfiguration until needed; escalate to deliberation when the user’s state nears decision boundaries detected as geometric saddle crossings.

- Tools/products: “Dual-Mode UI Orchestrator” that ties clickstream features to η, detects phase transitions, and schedules prompts or deeper wizards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Event-to-state mapping; user consent and explainability; minimizing false-positive escalations.

- Risk-aware trading copilots with fast heuristics and slow analysis

- Sectors: finance, fintech

- Use case: Provide instant heuristic trades under stable regimes (fast h) while accumulating macro, news, and portfolio constraints over slower timescales (slow c); alert on landscape reconfigurations (e.g., regime shifts).

- Tools/products: “Dual-Process Trading Assistant” with J_reward (expected utility), J_norms (risk/compliance), J_effort (compute/cost), “PhaseSwitch Monitor” for regime shift detection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust data pipelines; compliance encoding into J; backtesting and guardrails; clear operator override.

- A common research toolkit for “potential engineering” and “metric learning”

- Sectors: academia, AI research

- Use case: Build and share reusable components for designing J (accuracy/utility/norms/effort) and learning G (Riemannian preconditioning) across tasks; create benchmark suites showing emergent dual-process behavior.

- Tools/products: “PotentialComposer” (library to specify J terms), “MetricLearner” (learn G from data), visualization of slow manifolds and time-scale separation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standardized datasets; API integration with PyTorch/JAX; reproducible experimental protocols.

Long-Term Applications

The following list describes use cases that require additional research, scaling, learning robust J and G from rich data, or new infrastructure.

- General-purpose agents (AGI) with a learned cognitive manifold and unified potential

- Sectors: AI/AGI, software

- Use case: End-to-end agents whose latent state η unifies perception, memory, action, and reasoning; J integrates accuracy, utility, norms, and effort; G shapes multi-timescale behavior without modular hard-coding.

- Tools/products: “Cognitive Manifold Engine” with end-to-end learning of J and G; dataset curation pipelines; evaluation on generalist tasks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scalable training; stability guarantees; robust generalization; safety and alignment.

- Formalized normative reasoning embedded in the potential (AI alignment)

- Sectors: AI governance, policy

- Use case: Encode social, legal, and ethical constraints in J_norms; analyze trade-offs with reward and effort; ensure monotonic decrease of violation risk along trajectories.

- Tools/products: “Norms-to-Potential Compiler” that translates policy/regulation into differentiable constraints; auditing tools for geometric trajectories.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Formalization of norms; measurable proxies; auditing standards; multi-stakeholder oversight.

- Personalized clinical cognition models for therapy and decision-making

- Sectors: healthcare

- Use case: Estimate individual-specific metric anisotropies (effort, habit strength) and potentials to tailor interventions (e.g., habit reversal, cognitive load management); predict when patients may switch decisions or relapse.

- Tools/products: “Patient Cognitive Geometry Profiler,” “Slow-Manifold Intervention Planner.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Longitudinal data; clinical trials; explainability and consent; integration with EHR systems.

- Crisis-management platforms with dual-process operational pipelines

- Sectors: public policy, emergency response

- Use case: Design protocols with fast defaults (evacuation heuristics) and slow strategic updates (resource reallocation) informed by geometric phase-transition detection.

- Tools/products: “Dual-Process Ops Console” with decision basins visualization; phase-transition alerts; oversight workflows.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable sensing and data assimilation; governance frameworks; operator training.

- Generalist robots that unify reflexes, planning, and social inference

- Sectors: robotics, logistics

- Use case: Robots that learn G and J across perception–action–interaction, allocating compute automatically across time scales; handle abrupt context shifts through phase-transition dynamics.

- Tools/products: “Geometric Cognitive Controller” with learned metric across subsystems; multi-agent extension for social norms in J.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Large-scale multimodal data; safety and verification; sim-to-real robustness.

- Multiscale portfolio and grid-management systems

- Sectors: finance, energy

- Use case: Encode risk, compliance, and utility in J; reflect operational costs in G; produce fast hedging under routine conditions and slow rebalancing across macro shifts; detect regime transitions.

- Tools/products: “Gradient-Flow Portfolio Manager,” “Grid Ops Geometry Planner.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-fidelity forecasting; regulation-aware potentials; resilient infrastructure.

- Neuromorphic or accelerator hardware for Riemannian gradient flows

- Sectors: semiconductors, AI infra

- Use case: Hardware primitives for metric-aware optimization and continuous-time flows on latent manifolds; efficient computation of G−1∇J and manifold projection.

- Tools/products: ASICs/accelerators with native Riemannian kernels; runtime for slow-manifold tracking.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware design investment; compiler support; standardized interfaces.

- Lifelong learning systems that shape student-specific geometry

- Sectors: education

- Use case: Continually learn a student’s metric anisotropies (effort, habituation) and potential components; schedule tasks across time scales to balance load and long-term mastery.

- Tools/products: “Cognitive Geometry LMS,” “Phase-Aware Curriculum Designer.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Long-term data collection; privacy-preserving modeling; fairness assessment.

- Scientific discovery assistants over hypothesis manifolds

- Sectors: academia, R&D

- Use case: Represent hypotheses and constraints as η with J capturing fit, parsimony, and norms; use slow drift for exploration and phase transitions for commitment to promising lines of inquiry.

- Tools/products: “Gradient-Flow Lab Assistant” with manifold visualization; evidence integration pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality domain priors; collaborative tooling; provenance tracking.

- Workplace productivity and planning with slow-manifold oversight

- Sectors: enterprise software

- Use case: Schedule fast task execution vs slow strategic planning; monitor when plans should switch (phase transitions) based on evidence and constraints encoded in J.

- Tools/products: “Dual-Process Planner,” “PhaseSwitch Project Manager.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational data access; user acceptance; careful UX to avoid alert fatigue.

Cross-cutting workflow blueprint (applies to many items above)

To implement the framework in practice:

- Define a latent cognitive state η and select observable proxies.

- Engineer J by composing differentiable terms for accuracy/utility (J_reward), parsimony (J_complexity), norms (J_norms), and resource/effort (J_effort).

- Choose or learn a Riemannian metric G; use block-anisotropic structures to realize fast–slow separation.

- Run the Riemannian gradient flow; track convergence to the slow manifold; monitor curvature-induced phase transitions.

- Expose interpretable dashboards (energy landscape, basins, manifold proximity), and define safe escalation/handoff policies.

Key dependencies include: a reliable η–observation mapping, differentiability of J and G, data for learning/calibration, safety/ethics encoding in J_norms, compute/latency budgets, and governance for deployment in sensitive domains.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.