- The paper's main contribution is a nonlinear evolution equation that predicts the emergence of rotating polygonal patterns as cnoidal wave solutions.

- It employs detailed geometric and kinematic modeling, incorporating curvature effects and vortex dynamics to match experimental polygon shapes.

- The study bridges theory with experiment, demonstrating quantitative agreement and offering insights into pattern transitions and symmetry-breaking instabilities.

Modeling Self-Organized Leidenfrost Rotating Polygons as Cnoidal Waves

Introduction

This work presents a theoretical analysis of the spontaneous formation of rotating polygonal patterns at the inner boundary of Leidenfrost rings, motivated by observations in shallow liquid nitrogen systems. It addresses a prominent open problem in nonlinear hydrodynamics: predicting the emergence of regular, sharp-cornered rotating polygons driven by nonlinear interactions between surface tension, rotational flows, and geometric confinement. By formulating and analyzing a nonlinear evolution equation that systematically accounts for curvature effects, rolling vortex flow, and nonlinear momentum terms, the study rigorously demonstrates that these polygonal patterns correspond to cnoidal wave solutions—specifically Jacobi elliptic function solutions—on a circular contour, with parameters constrained by both physical system properties and experimental measurements (2512.11924).

Experimental Phenomenology: Rotating Leidenfrost Polygons

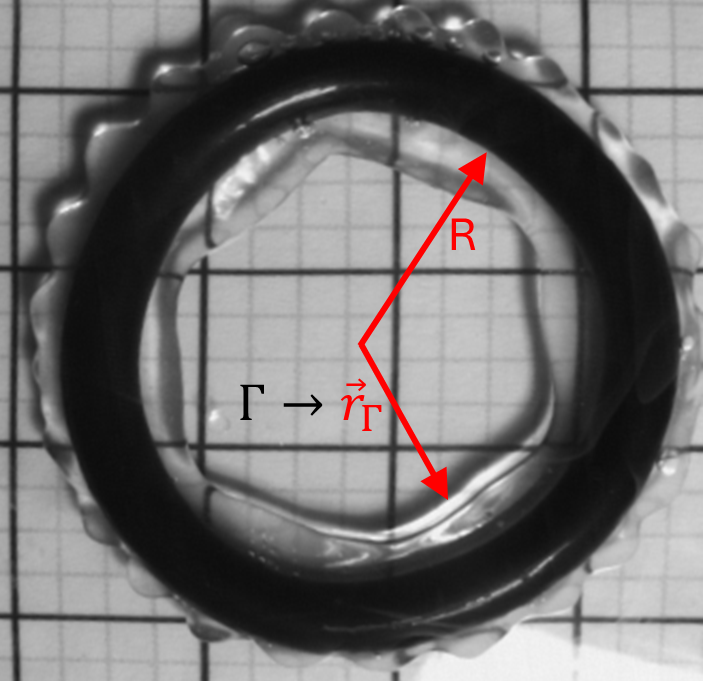

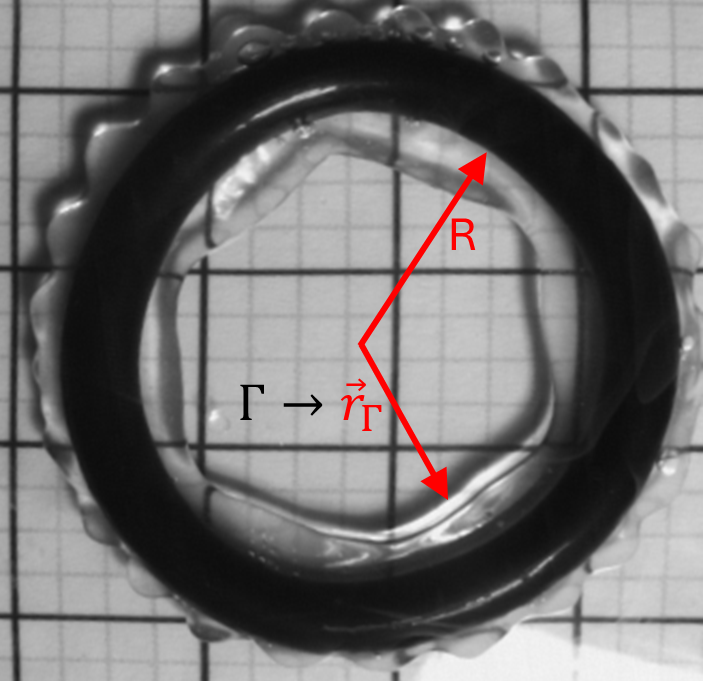

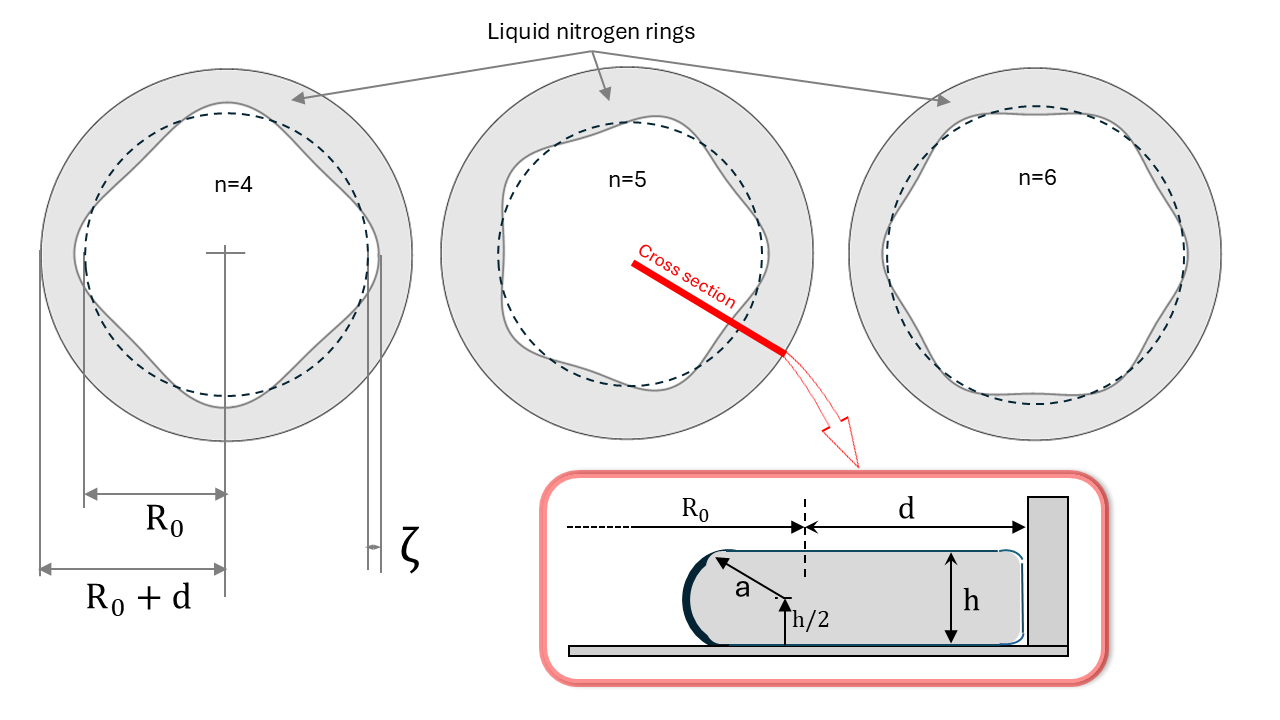

The experimental system consists of a volume of liquid nitrogen placed as a ring inside a cylindrical wall on a substrate far above the Leidenfrost temperature, producing a levitated layer with minimal direct contact. Critical to maintaining this state is a layer of nitrogen outside the ring, used for thermal regulation. Under these conditions, oscillatory and rotational instabilities generate regular polygonal patterns with 4 to 8 edges at the inner free surface (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Typical liquid nitrogen Leidenfrost ring formation in a rigid cylinder, illustrating the geometric and physical setup central to pattern formation.

Following the suppression of Rayleigh–Taylor bubble formation via controlled evaporation cycles, the system enters a regime where buoyancy-driven and thermocapillary convection generate vertical rolling vortices along the liquid’s inner surface. This coupling of nonlinear free-surface oscillations and poloidal rotational flows creates the conditions for robust formation of stationary or steadily rotating polygonal boundaries distinct from linear azimuthal oscillations.

Theoretical Framework and Nonlinear Modeling

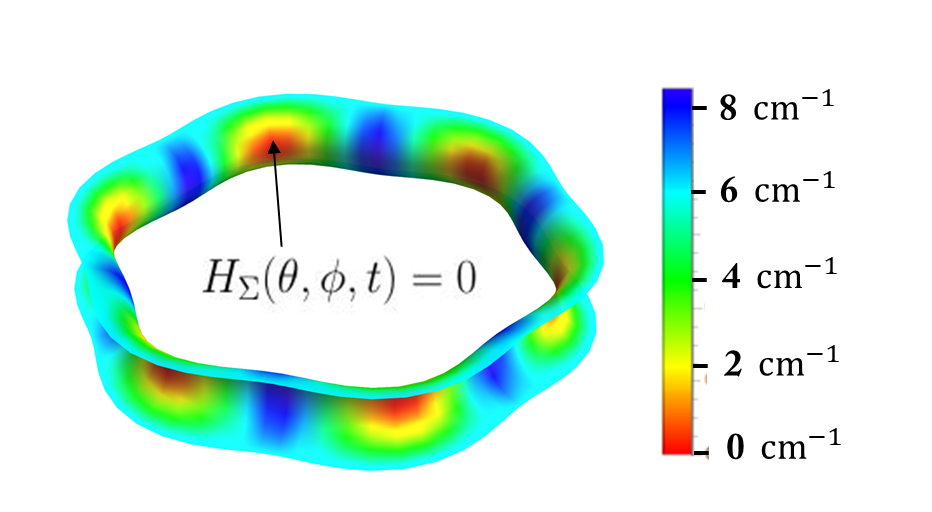

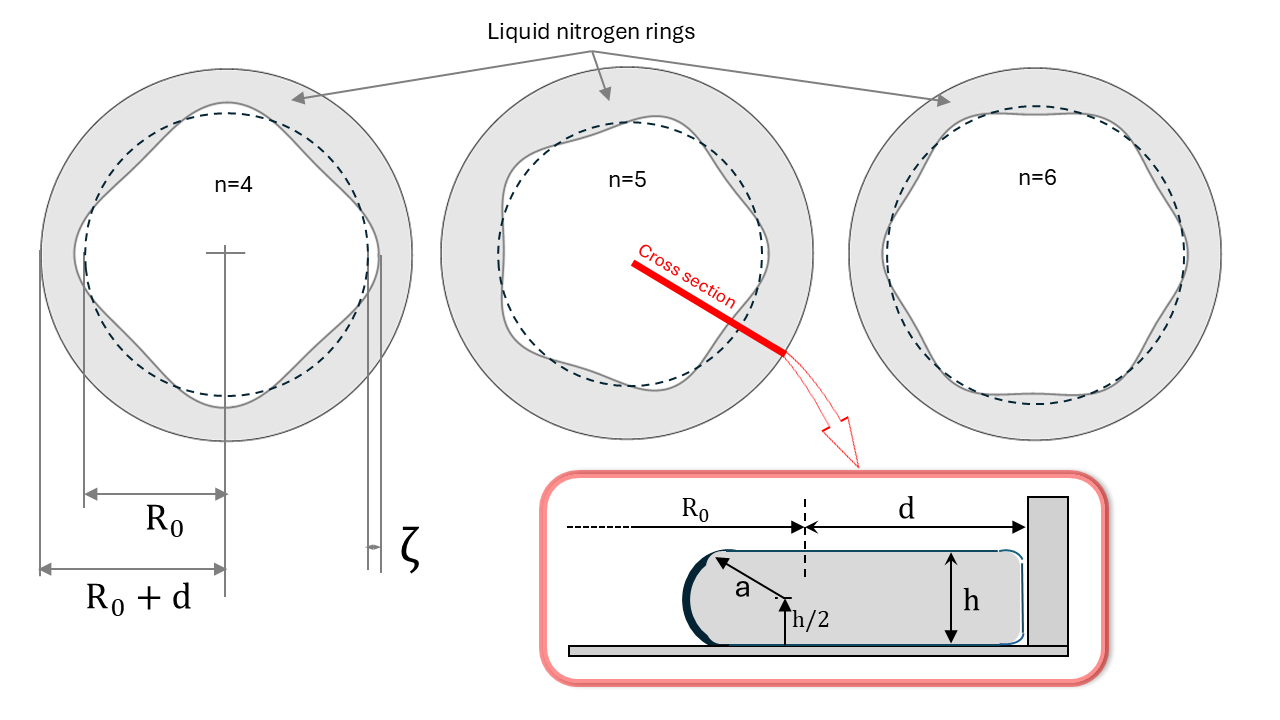

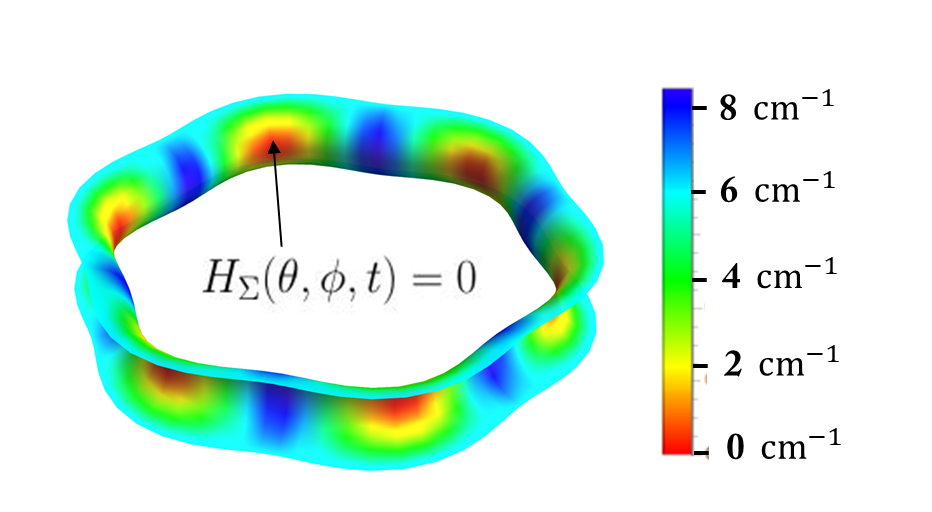

The core theoretical advancement is the derivation of a nonlinear evolution equation governing the azimuthal deformation γ(θ,t) of the inner boundary. The modeling employs the Euler equation for an incompressible, shallow, inviscid fluid in the Boussinesq approximation, incorporating a Helmholtz-Hodge decomposition to separate potential and rotational velocity components. Surface tension is represented by a full Young–Laplace pressure term, expanded up to cubic order in local geometric deformation, with the mean curvature HΣ of the inner surface explicitly parametrized in terms of the local geometry (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Figure 2: Geometry and parametrization of the Leidenfrost ring and inner surface—the cross-section illustrates how azimuthal deformations are captured.

Figure 3: A hexagonal deformation of the inner free boundary, visualizing the mean curvature distribution on Σ relevant to capillary pressure.

The principal contributions are:

- Nonlinear kinematic boundary conditions and Laplace expansion: The velocity potential is developed as a power series in the radial coordinate, with corrections retaining terms up to O(γ3). This enables explicit handling of the coupling between surface geometry and flow.

- Explicit mean curvature calculation: The pressure jump at the free surface is cast in terms of the full mean curvature, capturing both in-plane and out-of-plane effects—a necessity for modeling the sharply peaked vertices of the observed polygons.

- Inclusion of vortical (rolling) flows: The impact of poloidal rolling vortices is modeled via the vortex Reynolds number ReΓ, introducing a robust representation of buoyancy-driven and thermocapillary-induced rotational motions.

- Final evolution equation: In the co-rotating frame ξ=θ−Ωt, the resulting nonlinear ODE possesses dominant convective, dispersive, and geometric nonlinearities—allowing for the existence of periodic, strongly nonlinear wave solutions (cnoidal waves) corresponding to the observed polygons:

–(dΩ2R03+C1)γ′+C2γγ′+⋯+D1γ′′′+⋯=0

with C1,C2,D1 and additional terms encapsulating curvature, rotational flow, and nonlinear momentum effects.

Cnoidal Wave Solutions and Polygonal Pattern Selection

The analysis demonstrates that stationary solutions of the nonlinear equation are given by cnoidal waves, i.e.,

γ(ξ)=s2+(s3−s2)cn2[p(ξ−s3)∣m]

where p (wavelength), m (modulus), and s2,3 (amplitude bounds) are determined by the physical parameters of the system and by fitting to experimentally measured polygon geometry (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Examples of cnoidal wave solutions representing 4-, 5-, and 6-sided rotating polygons in the co-rotating frame.

The key technical findings include:

- Existence and parametrization: The cnoidal wave family naturally generalizes trigonometric (cosine) oscillations to the nonlinear regime. For fixed system parameters, only discrete values of m and p admit n-edged periodic solutions (Figure 5, Figure 6).

- Polygon selection: The matching conditions for experimentally observed polygons—number of vertices, amplitude, sharpness of peaks—are enforced by numerically solving for the cnoidal parameters compatible with the ring geometry, tension, and rotational velocity (Figure 7, Table I).

- Limiting behavior: With increasing modulus m→1, the cnoidal solutions become localized solitonic pulses, connecting with previously proposed sech2 envelope models. In the opposite limit m→0, regular rounded polygons are retrieved.

Figure 5: Dependence of the cnoidal parameter m on the spatial parameter p for different polygonal modes, delineating the admissible regime for n=3…8.

Figure 6: Direct comparison between linear (blue) and nonlinear cnoidal (black) solutions for given polygonal shapes, highlighting the curvature enhancement at vertices in the nonlinear case.

Numerical and Experimental Validation

Direct experimental measurements—polygon count, angular velocity, aspect ratio, and amplitude—are used to fit the four free parameters (ReΓ, a0, ϵ, δ) of the theoretical model. The model produces strong quantitative agreement with observed patterns for n=4 (square), n=5 (pentagon), n=6 (hexagon), and n=8 (octagon) (Figures 6, 7, 8).

Figure 7: Experimental images of n=4 (left) and n=5 (right) polygons, with overlaid theoretical cnoidal solutions (light green), demonstrating high-fidelity fit.

Figure 8: High-contrast image of n=6 polygon (left) and a peaked polygon (right), fitted to both cnoidal and trigonometric solutions respectively.

Table I documents the matching procedure, showing detailed agreement between theoretical and observed angular velocities, vortex Reynolds numbers, deformation amplitudes, and elliptic parameters for different polygonal states.

Model Simplification and Analytical Results

Averaging the surface tension term over the poloidal angle yields a Korteweg–de Vries (KdV) reduction, which admits solutions in terms of elliptic functions (cnoidal waves) or, with radial flow contributions, exact trigonometric solutions exhibiting peaked concave polygons. The KdV reduction is corroborated experimentally, validating both its analytical tractability and predictive power.

Figure 9: Example plots for mean curvature HΣ as a function of angle for characteristic polygonal deformation, essential for evaluating the full nonlinear pressure jump.

Implications, Limitations, and Outlook

The study rigorously anchors the selection and stability of rotating polygonal patterns in a Leidenfrost ring to the existence and properties of cnoidal wave solutions of a fully nonlinear, geometry-resolved evolution equation. The results clarify the role of geometric nonlinearity, rotational inertia, and surface tension in pattern selection and show that viscous and detailed thermocapillary effects are subdominant for the regimes explored. The formalism provides a platform for studying polygon transitions, bifurcations, and potential instabilities as system parameters evolve (e.g., via evaporation-driven radius shrinkage).

Limitations include the neglect of viscosity and vapor-layer shear, absence of real-time temperature profiling, and the use of matched empirical parameters in lieu of first-principles closure. Extensions should incorporate three-dimensional temperature and momentum fields, the effect of weak dissipation, and higher-order geometric perturbations for a full stability and transition analysis.

Conclusion

This work presents a comprehensive nonlinear theory for self-organized polygonal structures in Leidenfrost rings, connecting observed pattern formation to cnoidal wave solutions parameterized by measurable quantities. The explicit inclusion of geometric, vortical, and capillary effects enables both accurate quantitative prediction and deeper mechanistic insight into symmetry-breaking instabilities in free-surface hydrodynamics. This methodology is anticipated to underpin future analyses of similar pattern-forming systems across fluid mechanics, geophysical vortices, and capillary-dominated regimes (2512.11924).