E-RayZer: Self-supervised 3D Reconstruction as Spatial Visual Pre-training (2512.10950v1)

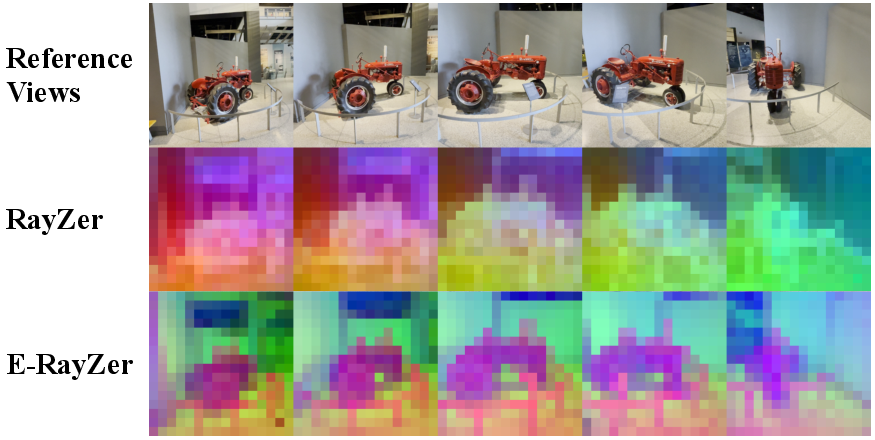

Abstract: Self-supervised pre-training has revolutionized foundation models for languages, individual 2D images and videos, but remains largely unexplored for learning 3D-aware representations from multi-view images. In this paper, we present E-RayZer, a self-supervised large 3D Vision model that learns truly 3D-aware representations directly from unlabeled images. Unlike prior self-supervised methods such as RayZer that infer 3D indirectly through latent-space view synthesis, E-RayZer operates directly in 3D space, performing self-supervised 3D reconstruction with Explicit geometry. This formulation eliminates shortcut solutions and yields representations that are geometrically grounded. To ensure convergence and scalability, we introduce a novel fine-grained learning curriculum that organizes training from easy to hard samples and harmonizes heterogeneous data sources in an entirely unsupervised manner. Experiments demonstrate that E-RayZer significantly outperforms RayZer on pose estimation, matches or sometimes surpasses fully supervised reconstruction models such as VGGT. Furthermore, its learned representations outperform leading visual pre-training models (e.g., DINOv3, CroCo v2, VideoMAE V2, and RayZer) when transferring to 3D downstream tasks, establishing E-RayZer as a new paradigm for 3D-aware visual pre-training.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces E-RayZer, a computer vision model that can learn true 3D understanding from ordinary videos and photo sequences without needing any human-provided labels. Think of it like teaching a computer to build a 3D LEGO model of a place just by looking at several photos taken from different angles—and doing it without anyone telling the computer the camera details or the shape of the scene.

What questions does the paper try to answer?

To make the explanation easier to follow, here are the main goals of the research in simple terms:

- Can a model learn real 3D geometry from unlabeled images rather than just “faking” 3D by image tricks?

- Can it figure out where each camera was (its position and direction) and what the scene looks like in 3D, all by itself?

- Can this learning style produce better features that help with other tasks, like estimating depth, camera poses, or motion between images?

- Can it match or beat models that rely on supervision (models trained with ground-truth 3D labels), even when it has zero 3D labels?

How did they do it?

The key idea is to make the model work directly in 3D, not just in “hidden” feature space. Here’s how:

- Self-supervised learning: This means the model learns without human-provided labels. Instead, it sets itself a puzzle and learns by trying to solve it. The puzzle here is: “Render a new view of the scene and make it look exactly like the real photo taken from that viewpoint.”

- Camera poses: A “camera pose” describes where the camera was and where it was pointing. The model predicts:

- Extrinsics: Position and orientation in space (like “standing near the door, facing the window”).

- Intrinsics: Lens settings (like focal length), which affect how the image is formed.

- Explicit 3D geometry using “3D Gaussians”: Imagine filling the scene with many tiny, fuzzy colored balls (“Gaussians”). By placing these balls at the right positions, sizes, orientations, and colors, the model can render an image from any camera viewpoint. This method is called “3D Gaussian splatting,” and it’s powerful because:

- It’s physically grounded: The model must place balls in 3D space in ways that make sense.

- It’s differentiable: The computer can measure how the rendered image differs from the real photo and use that difference to adjust the balls and camera parameters to improve.

- Photometric loss: This is the “spot-the-difference” score between the rendered image and the real image. If they don’t match, the model tweaks the camera and the Gaussians to get closer.

- Curriculum learning based on “visual overlap”: Training from scratch in full 3D is hard. To make it easier, the authors designed a curriculum (like starting with easy exercises and then moving to harder ones):

- Early on, the model sees pairs of images that look very similar (high overlap), which makes finding camera poses easier.

- Later, it practices on more challenging pairs with less overlap.

- The “visual overlap” is measured either by:

- Semantic similarity (how similar the images look in terms of features), or

- Geometric covisibility (how much of the scene is shared between views).

- This curriculum works across different datasets without needing any 3D labels.

- Avoiding shortcuts: Previous work (RayZer) could cheat by learning image interpolation (like “blending” frames) rather than real 3D. E-RayZer removes cues that encourage such shortcuts (like index-based tokens), and builds in gentle 3D biases through its architecture and explicit Gaussians so the model learns real spatial understanding.

What did they find and why does it matter?

Here are the main results, explained simply:

- Better camera poses: E-RayZer predicts much more accurate camera positions and directions than previous self-supervised models. This shows it understands the 3D structure of scenes more reliably.

- Competitive or better than supervised models: In several tests, E-RayZer performs on par with, or even better than, strong supervised models like VGGT that were trained using ground-truth 3D labels. That’s impressive because E-RayZer doesn’t use any 3D labels at all.

- Strong pretraining for 3D tasks: The features learned by E-RayZer transfer well to other tasks that need 3D awareness, such as:

- Depth estimation: How far things are from the camera.

- Pose estimation: Figuring out how cameras moved.

- Optical flow: Tracking how pixels move between frames.

- In many cases, E-RayZer beats popular pretraining models like DINOv3, CroCo v2, VideoMAE V2, and Perception Encoder when tested on 3D-focused tasks.

- Boosts supervised models: If you start a supervised model like VGGT with E-RayZer’s learned weights (instead of random initialization), it gets noticeably better. That means E-RayZer is a powerful general-purpose pretraining tool for visual geometry.

Why it matters:

- It shows that we can learn real 3D understanding from raw images without expensive 3D annotations, making training more scalable and practical.

- It makes camera pose estimation more geometrically consistent and interpretable, which helps many downstream applications.

What is the impact?

If computers can learn 3D from regular videos and photos without labels, we can build much better and more scalable systems for:

- AR/VR and gaming: Quickly reconstruct rooms, streets, or objects in 3D from a phone video.

- Robotics: Help robots understand their surroundings and navigate safely without precise maps.

- Mapping and surveying: Create 3D maps from video footage, even in new or challenging environments.

- Content creation: Enable fast 3D scene capture for movies or virtual sets.

Big picture: E-RayZer sets a new path for “3D-aware” visual pretraining. Instead of relying on labels and “fake 3D” tricks, it makes the model reason directly in 3D. That can lead to more accurate, interpretable, and broadly useful vision systems that understand the physical world.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved Gaps, Limitations, and Open Questions

The paper introduces E-RayZer as a self-supervised, explicit-geometry 3D Gaussian splatting model with a visual-overlap curriculum. While promising, several concrete gaps remain that future work could address:

- Camera intrinsics modeling is limited to a 3×3 matrix; the system does not model lens distortions, rolling shutter, zoom/focal variability across frames, or per-frame intrinsics changes common in heterogeneous datasets.

- Absolute scale remains ambiguous under pure photometric self-supervision; the paper does not evaluate or constrain metric scale, nor quantify scale drift across sequences.

- The relative pose accuracy (RPA) metric conflates rotation and translation; separate analyses for rotation, translation direction, and translation magnitude would clarify what aspects improve and where the method still fails.

- The approach assumes one 3D Gaussian per pixel per ray, implicitly modeling a single dominant surface; there is no mechanism for multi-layer geometry along rays (transparency, translucency, thin structures), nor a learned strategy to fuse and deduplicate cross-view Gaussians.

- No explicit occlusion reasoning or visibility modeling (e.g., learned occlusion masks, z-buffering constraints) is used in the photometric supervision, which may hinder learning under wide baselines or heavy occlusions.

- The shading/color model (spherical harmonics on Gaussians) does not account for view-dependent appearance, non-Lambertian materials, or illumination changes; the paper does not analyze failure modes in specular or glossy scenes.

- The photometric losses (MSE + perceptual) are not robustified for exposure changes, motion blur, noise, or camera auto white balance; the method’s sensitivity to appearance shifts remains unquantified.

- The modified gsplat to backpropagate to intrinsics is not specified or analyzed for numerical stability (e.g., gradient conditioning, sensitivity to focal length), nor is it open-sourced or benchmarked for correctness against known calibration tasks.

- The curriculum relies on a precomputed “visual overlap” profile; there is no end-to-end, online difficulty estimation or adaptive sampling strategy that updates based on current model competence.

- The geometric overlap variant uses UFM covisibility trained with 3D annotations; the pipeline’s dependence on a 3D-supervised auxiliary tool undermines the “from scratch without any 3D annotation” claim. A fully self-contained, unsupervised alternative is not provided.

- The semantic overlap variant depends on DINOv2 features (trained self-supervised on large image corpora); how biases in DINOv2 features affect curriculum quality and domain transfer is not studied.

- The chosen curriculum schedules (semantic: 1.0→0.75; geometric: 1.0→0.5) are heuristic; the paper does not explore principled schedule design, schedule sensitivity, or whether per-dataset schedules are optimal.

- Global attention over all tokens has quadratic complexity O((K_ref·h·w)2); scalability to high resolutions, long sequences, and large batch sizes is not characterized, and efficient alternatives (sparse/hierarchical attention) are not investigated.

- Runtime, memory footprint, and throughput at train and inference time (including the explicit splatting render) are not reported; the practical cost of scaling to web-scale datasets and real-time applications is unknown.

- The architecture removes index embeddings to discourage interpolation shortcuts but does not formally rule out other shortcuts; there is no causal or diagnostic analysis of remaining shortcut behaviors.

- E-RayZer predicts per-view relative poses with a pairwise camera head; global multi-view consistency (loop closure, drift over longer sequences, bundle-level coherence) is not evaluated or enforced.

- The approach splits views into non-overlapping reference/target sets; the effect of alternative splits (e.g., dynamic grouping, leave-one-out cross-rendering, cross-view fusion strategies) is not studied.

- The method does not integrate geometric constraints beyond photometric rendering (e.g., epipolar consistency, differentiable reprojection errors, cycle-consistency), leaving potential accuracy gains unexplored.

- Explicit 3D reconstruction quality (e.g., geometric accuracy of the Gaussian field, point cloud/mesh fidelity, chamfer/L2 metrics against ground truth geometry) is not directly evaluated; the focus is on PSNR and pose accuracy.

- Robustness to dynamic scenes (moving objects, non-rigid motion), temporal changes (lighting, weather), and challenging domains (textureless areas, repetitive patterns, symmetries) is only anecdotally discussed; there is no systematic stress test.

- The method is trained with 10 views; sensitivity to number of views, view distribution (narrow vs. wide baselines), and robustness to missing/corrupted views is not reported.

- Heterogeneous data scaling is presented, but detailed analysis of cross-dataset domain shift (sensor differences, intrinsics variability, resolution changes) and ablations on mixing ratios are limited.

- The data mixing and curriculum only consider “visual overlap”; other difficulty dimensions (scene scale, indoor/outdoor, motion patterns, texture richness) are not modeled in sampling.

- The flow downstream task shows RayZer outperforming E-RayZer on EPE; the paper does not analyze why explicit 3D pretraining underperforms on 2.5D flow or how to improve binocular geometry encoding.

- Transfer evaluations cover depth, pose, and flow; broader 3D tasks (surface normal estimation, semantic 3D segmentation, multi-view stereo, pointmap prediction) and embodied tasks (SLAM, AR tracking) are not explored.

- Integration with multimodal signals (depth sensors, IMU, LiDAR), multi-camera rigs, or text/semantics to improve 3D understanding is not addressed.

- Regularization of Gaussian parameters (scale, opacity, orientation) to avoid degenerate solutions (overgrowth, collapse, excessive opacity) is not specified, nor are failure cases analyzed.

- The claim of being “truly self-supervised” is not reconciled with reliance on pretrained feature extractors (DINOv2) or 3D-supervised UFM for curriculum labeling; a principled definition and audit of self-supervision in the overall pipeline is missing.

- Code availability for the modified renderer and training pipeline is referenced but not detailed in the paper; reproducibility (hyperparameters, data preprocessing, curriculum labeling protocol) needs a thorough checklist and ablation to ensure replicability.

Glossary

- AbsRel: Absolute Relative Error, a depth metric equal to mean(|pred−gt|/gt). "We evaluate absolute relative error (AbsRel)"

- COLMAP: A Structure-from-Motion system that estimates camera poses and sparse/dense geometry from images. "COLMAP~\cite{schonberger2016structure}"

- Covisibility: The amount of 3D scene content simultaneously visible from two views. "a geometric version that computes actual covisibility"

- Curriculum learning: A training strategy that orders samples from easy to hard to stabilize and improve learning. "we propose a learning curriculum based on the concept of visual overlap between input views"

- Differentiable rendering: Rendering whose outputs are differentiable w.r.t. scene and camera parameters, enabling gradient-based learning. "3D Gaussians support closed-form differentiable rendering"

- DPT head: A Dense Prediction Transformer head used to regress dense maps like depth from features. "we apply a DPT head~\cite{ranftl2021vision}"

- End-point error (EPE): The average Euclidean distance between predicted and ground-truth optical flow vectors. "the average end-point error (EPE)"

- Extrinsics: Camera pose parameters (rotation and translation) that place the camera in world coordinates. "predict camera intrinsics and extrinsics for all input images"

- Gaussian splatting (3DGS): Modeling scenes as collections of 3D Gaussian primitives that are rasterized (“splatted”) for rendering. "E-RayZer is the first self-supervised feedforward 3DGS reconstruction model"

- gsplat: A software library for differentiable 3D Gaussian splatting. "we modify gsplat~\cite{ye2025gsplat} to support gradient back-propagation to camera intrinsics ."

- Inductive bias (3D inductive bias): Architectural or modeling assumptions that encourage learning 3D-consistent solutions. "contains almost no 3D inductive bias"

- Intrinsics: Camera internal calibration parameters (e.g., focal length, principal point) forming the matrix K. "predict camera intrinsics and extrinsics for all input images"

- Latent-space novel-view synthesis: Generating target views by rendering from learned latent features rather than explicit 3D geometry. "proxy tasks of latent-space novel-view synthesis"

- Multi-view transformer: A transformer architecture that aggregates information across multiple input views. "using a multi-view transformer $f_{\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\text{cam}$"

- Novel-view Synthesis (NVS): Rendering images from viewpoints not present in the input. "Comparison with (Partially) Self-supervised Methods on Novel-view Synthesis (NVS) and Pose Estimation."

- Pairwise Flow Estimation: Predicting optical flow between a pair of images. "Pairwise Flow Estimation (2.5D Task)."

- Perceptual loss: An image similarity measure computed in a deep feature space rather than pixel space. "perceptual loss~\cite{johnson2016perceptual}"

- Photometric loss: A pixel-level reconstruction loss (e.g., MSE) between rendered and target images. "and applies photometric loss as self-supervision:"

- Plücker ray map: A per-pixel representation of camera rays using Plücker coordinates, aligned to image pixels. "pixel-aligned Plücker ray map"

- PSNR: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio; a reconstruction quality metric for images. "We report PSNR for NVS"

- Quaternion: A 4D representation for 3D rotations used to parameterize Gaussian orientations. "orientation represented as a quaternion"

- Relative Pose Accuracy (RPA): Accuracy of estimated relative camera pose measured by angular thresholds. "relative pose accuracy (RPA)"

- SE(3): The Lie group of 3D rigid motions (rotations and translations). "$\mathbf{T}_i = [\mathbf{R}_i \,|\, \mathbf{t}_i] \in SE(3),"

- Self-supervision: Learning signals derived from the data itself without manual labels. "Self-supervised pre-training has revolutionized foundation models"

- Spherical harmonic coefficients: Parameters of SH basis functions used to model view-dependent color of Gaussians. "spherical harmonic coefficients"

- Tokenization: Converting inputs into sequences of tokens for transformer processing. "patch-wise linear projection for fusing and tokenizing RGB and ray information."

- UFM covisibility: A covisibility metric computed by the UFM method for geometric overlap. "geometric overlap (UFM~\cite{zhang2025ufm} covisibility"

- VGGT: A supervised model that predicts camera poses and geometry with strong multi-view reasoning. "VGGT~\cite{wang2025vggt}"

- Visual overlap: The degree of content overlap between input views used to control training difficulty. "visual overlap between input views"

Practical Applications

Overview

Below are actionable, real-world applications derived from the paper’s findings and innovations (explicit 3D self-supervision with 3D Gaussians, feedforward camera and geometry prediction, and the visual-overlap curriculum). Each item names target sectors, suggests tools/products/workflows, and notes key assumptions/dependencies that affect feasibility.

Immediate Applications

These can be prototyped or deployed today using the released model, weights, or straightforward engineering.

- 3D vision pretraining to boost pose, depth, and flow models (Academia, Software/ML)

- Tools/workflows: Use E-RayZer weights as a drop-in backbone for VGGT-like pipelines (“E-RayZer→VGGT” pretrain-then-finetune), depth (DPT-style heads), optical flow heads; benchmarking on OOD datasets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires multi-view inputs during pretraining; GPU for inference on high-res; downstream heads still need labeled data for best results.

- Pseudo-label generation to replace or reduce COLMAP in dataset creation (Software/ML, Mapping/GIS)

- Tools/workflows: Batch inference to emit camera intrinsics/extrinsics and sparse 3D Gaussians; export poses for NeRF/GS training; automated data bootstrapping at scale.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Needs multi-view overlap and mostly static scenes; absolute scale is ambiguous without external cues (IMU/LiDAR/known baselines).

- Rapid camera tracking and scene solves for VFX/editorial (Media/Entertainment)

- Tools/products: Nuke/After Effects/Premiere plugins (“E-RayZerSolve”) for instant camera paths and proxy geometry from set footage; markerless solves; improved low-texture robustness over implicit methods.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Lighting changes, motion blur, rolling shutter, and heavy reflections may degrade accuracy; validation against a few known points recommended.

- Turntable/product capture to 3D assets from phone videos (E-commerce/Retail, Creative Tools)

- Tools/workflows: Capture app that predicts poses and 3D Gaussians, then converts to meshes or Gaussian splats for web viewers; quick SKU digitization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires smooth rotations and sufficient overlap; specular/transparent objects still challenging; mesh extraction from Gaussians may require post-processing.

- Site progress snapshots with minimal calibration (AEC/Construction)

- Tools/workflows: Worker takes quick multi-view photos; server infers camera poses and coarse 3D; aligns sessions via small set of anchors; compare weekly changes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Dynamic machinery/people break photometric assumptions; needs simple anchor management for cross-session alignment and scale.

- Offline drone mapping from uncalibrated imagery (Robotics, Mapping/GIS)

- Tools/workflows: Post-flight batch processing to derive poses and 3D Gaussians; export to point clouds/meshes; QA dashboard for overlap coverage and pose confidence.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires sufficient overlap and stable exposure; large outdoor scenes need tiling; GPS/IMU can provide metric scale if desired.

- Faster photogrammetry bootstrapping (Digital Twins, Heritage)

- Tools/workflows: Use E-RayZer to provide initial camera poses/intrinsics to photogrammetry suites (COLMAP/MVE) to reduce failures and runtime; improve robustness on low-texture areas.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Still benefits from downstream bundle adjustment; specular/transparent surfaces remain hard.

- Video stabilization and path smoothing (Mobile, Creative Tools)

- Tools/workflows: Use predicted camera trajectories for post-hoc stabilization or synthetic camera moves; integrate in mobile editors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Rolling shutter and fast motion can bias pose; temporal smoothing may be needed.

- AR prototyping from pre-captured scans (AR/VR)

- Tools/workflows: Precompute room-scale poses and coarse geometry from a short capture; author spatial anchors and occlusion proxies for AR scenes without full SLAM.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Works best in quasi-static environments; not a drop-in replacement for online SLAM.

- Visual-overlap curriculum as a data curation tool (Academia, Software/ML Ops)

- Tools/products: “Overlap Profiler” CLI to label sequences with geometric/semantic overlap and sample curricula across heterogeneous datasets; improves self-supervised scaling and stability.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Needs DINOv2 embeddings or UFM covisibility; for geometric labels, 3D supervision used in UFM might be unavailable—semantic variant is self-supervised.

- Insurance and property claims capture (Finance/Insurance, Real Estate)

- Tools/workflows: Guided capture app for quick multi-view recording; server-side pose/3D for adjuster review and measurement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires sufficient coverage; metric scale needs a known reference or device sensors.

- Teaching aids for multi-view geometry (Education)

- Tools/workflows: Classroom demos that visualize predicted rays, poses, and Gaussian primitives to explain epipolar geometry and reconstruction.

- Assumptions/dependencies: None beyond compute; ideal for higher-ed CS/vision curricula.

- Quality gates for data pipelines (Software/ML Ops)

- Tools/workflows: Use pose accuracy metrics and overlap scores to auto-filter problematic sequences (e.g., dynamic scenes, low overlap) before training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Thresholds must be tuned per domain; imperfect but practical heuristic.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, engineering, or scaling (e.g., dynamic scenes, real-time constraints, domain robustness).

- Real-time, self-supervised 3D perception on AR glasses/phones (AR/VR, Mobile)

- Tools/products: On-device feedforward camera tracking and coarse geometry for occlusion/placement without heavy optimization; fallback to SLAM as needed.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires model compression, low-latency gsplat rendering, and robustness to rolling shutter and rapid motion; dynamic scene handling.

- SLAM-light robotics stacks (Robotics)

- Tools/workflows: Replace some optimization-heavy steps (init, relocalization) with feedforward pose estimates and 3D priors; hybrid pipelines combining E-RayZer with BA/loop closure.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Loop-closure and long-term drift still need classical modules; dynamic obstacles and illumination changes remain hard.

- Internet-scale 3D indexing from user-generated content (Search, Mapping/GIS)

- Tools/products: Backend that infers poses/geometry from web videos to build searchable, spatially-consistent scene graphs and digital twins.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy/consent, GPS alignment, scale recovery, and dynamic content filtering; substantial compute infrastructure.

- Self-supervised multi-camera calibration for vehicles and robots (Autonomous Systems)

- Tools/workflows: Continuous calibration of intrinsics/extrinsics with minimal labels; improves robustness after repairs or temperature drift.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Moving platforms induce parallax with dynamic scenes; requires moving-object segmentation or robust photometrics.

- Medical 3D reconstruction from endoscopy/arthroscopy video (Healthcare)

- Tools/workflows: Unlabeled pretraining on large surgical video corpora for improved pose/depth in narrow-FOV, low-texture conditions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain shift is severe; specular fluids and tissue deformation violate static-scene assumptions; safety validation required.

- 3D-aware video generation and editing (Media/Entertainment)

- Tools/products: Use E-RayZer features to condition generative models for spatially consistent video synthesis, camera moves, relighting, and scene edits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires coupling with diffusion/NeRF/GS generators; strict 3D consistency across frames remains a research challenge.

- City-scale digital twins for planning and resilience (Public Sector/Policy, Energy)

- Tools/workflows: Crowd-sourced captures plus drones to maintain up-to-date digital twins for urban planning, energy audits, and disaster response.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Governance for data sharing, privacy, and bias; metric alignment and QA require auxiliary sensors and standards.

- Standardized “visual-overlap” data governance for multimodal/self-supervised training (Policy, ML Ops)

- Tools/products: Publish overlap-aware sampling standards and metadata to improve fairness and stability of large-scale self-supervised training across heterogeneous datasets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community adoption; tooling support across data hubs.

- On-device privacy-preserving 3D capture (Consumer, Security/Privacy)

- Tools/workflows: Local pose/geometry inference with only derived, non-identifying assets shared; federated fine-tuning to improve performance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Efficient models, secure enclaves, and robust differential privacy strategies.

- Unified 3D foundation models for embodied AI (Academia, Robotics)

- Tools/workflows: Pretrain with E-RayZer-style objectives, then co-train with language/action for manipulation, navigation, and spatial reasoning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scaling laws, multimodal alignment, and sim-to-real transfer; richer dynamics modeling.

- Industrial inspection and maintenance (Energy, Manufacturing)

- Tools/workflows: Pose/3D from unlabeled inspection videos to detect change over time in plants, wind farms, or pipelines; integrate with anomaly detection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Harsh lighting, reflections, and repetitive patterns; reliance on overlap and static-scene assumptions.

- Consumer-grade 3D scene capture as a phone feature (Mobile)

- Tools/products: “3D Scene” mode using a short sweep to produce sharable Gaussian/mesh scenes for social apps and furniture placement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: UX for guided capture; real-time or near-real-time inference on-device; conversion to standard formats (glTF/mesh/GS).

Notes on general assumptions across applications:

- Multi-view overlap and mostly static scenes are important for the photometric self-supervision underpinning the model.

- Absolute scale is not determined without external references (IMU, known baselines, or GPS/LiDAR).

- Challenging materials (transparent/specular), strong illumination changes, and heavy motion blur/rolling shutter can degrade performance.

- Compute and memory demands may preclude real-time mobile deployment without distillation/quantization.

- Converting 3D Gaussians to meshes or watertight assets requires additional processing, which may affect fidelity.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.