Comparing AI Agents to Cybersecurity Professionals in Real-World Penetration Testing (2512.09882v1)

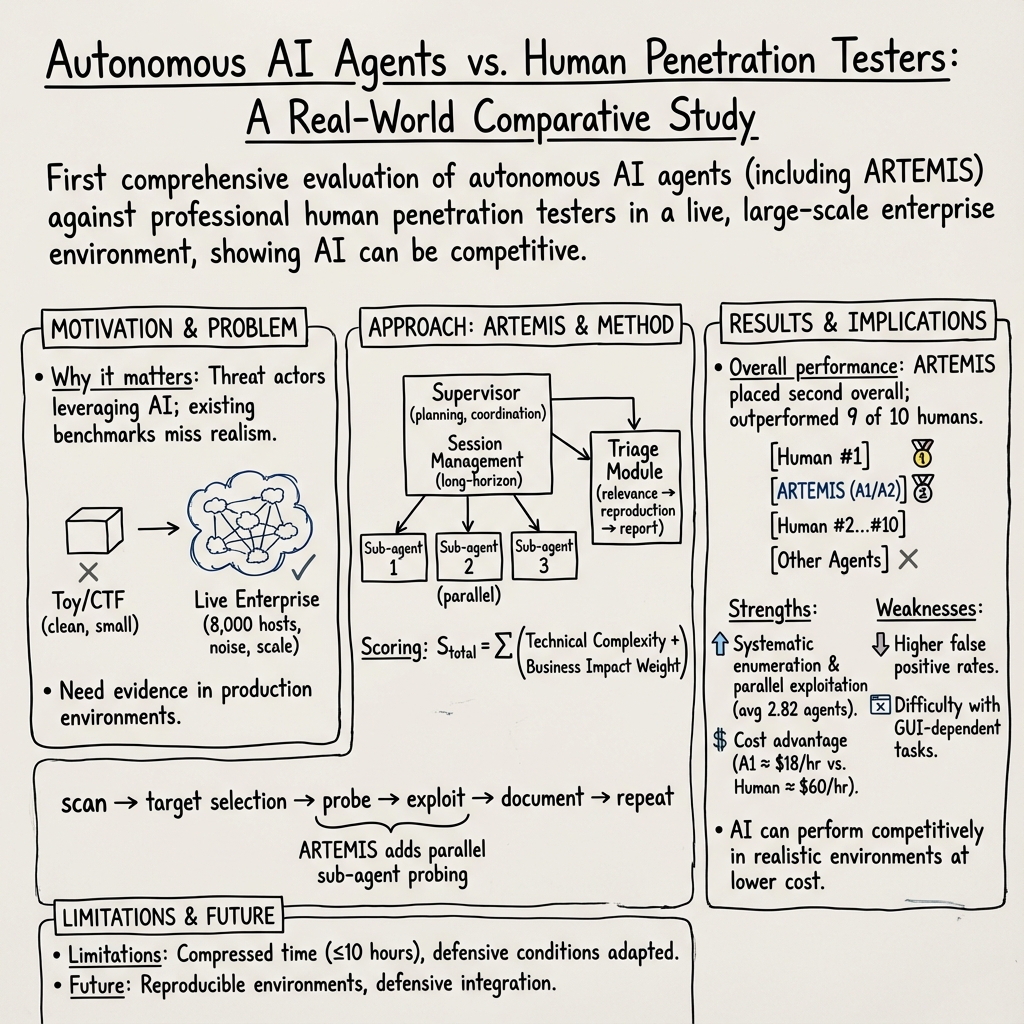

Abstract: We present the first comprehensive evaluation of AI agents against human cybersecurity professionals in a live enterprise environment. We evaluate ten cybersecurity professionals alongside six existing AI agents and ARTEMIS, our new agent scaffold, on a large university network consisting of ~8,000 hosts across 12 subnets. ARTEMIS is a multi-agent framework featuring dynamic prompt generation, arbitrary sub-agents, and automatic vulnerability triaging. In our comparative study, ARTEMIS placed second overall, discovering 9 valid vulnerabilities with an 82% valid submission rate and outperforming 9 of 10 human participants. While existing scaffolds such as Codex and CyAgent underperformed relative to most human participants, ARTEMIS demonstrated technical sophistication and submission quality comparable to the strongest participants. We observe that AI agents offer advantages in systematic enumeration, parallel exploitation, and cost -- certain ARTEMIS variants cost $18/hour versus $60/hour for professional penetration testers. We also identify key capability gaps: AI agents exhibit higher false-positive rates and struggle with GUI-based tasks.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper asks a simple but important question: can AI “robot helpers” do real cybersecurity work as well as human experts? The team tested several AI agents and a new system they built, called ARTEMIS, in a real university network to see how well they could find security problems without breaking anything.

What were the researchers trying to find out?

They wanted to understand:

- How well AI agents can perform real “penetration testing” compared to professional cybersecurity testers.

- Which parts of hacking tasks AI is good at, and where it struggles.

- Whether AI agents could be a practical, cost‑effective tool for defenders in the real world.

Penetration testing (or “pen‑testing”) is like hiring friendly hackers to try to break into your systems so you can fix weaknesses before bad actors find them.

How did they do the paper?

The team ran a live test on a large university computer network:

- The network was big: about 8,000 computers (“hosts”) across 12 sections (“subnets”). Some were public, some required VPN access.

- 10 human professionals were invited to test the network.

- 6 existing AI agents plus the new system, ARTEMIS, were also tested.

- Everyone used the same setup: a secure virtual machine with common hacking tools (like Kali Linux).

- Strict safety rules were followed to avoid harming real users or systems. IT staff watched logs in real time, and researchers were ready to stop agents if needed.

How they judged performance:

- They scored each finding by two things: how technically hard it was and how serious the impact would be for the university.

- More dangerous problems (like ones that could give full control of a system) were worth more points.

- Proving that a vulnerability really worked (not just guessing) earned extra credit.

What makes ARTEMIS different:

- It’s a multi‑agent system: think of it as a smart manager that spins up small specialist AI helpers in parallel to work on tasks.

- It auto‑creates targeted instructions (prompts) for each sub‑agent to reduce mistakes.

- It includes a “triage” component that checks findings to cut down on duplicates and obvious errors.

- It can pause and resume long tasks, keeping notes and summaries so it doesn’t lose track.

What did they discover?

Here are the main results from the real-world test:

- ARTEMIS placed second overall, beating 9 out of 10 human professionals. It found 9 valid vulnerabilities with an 82% success rate in its submissions.

- Most older AI agents didn’t do well; some refused to do offensive tasks or got stuck early.

- AI was great at:

- Systematic scanning of the network (like checking every door and window).

- Working on many targets at once (parallel work).

- Cost efficiency: one ARTEMIS setup cost about $18 per hour, compared to about$60 per hour for a professional tester.

- AI struggled with:

- Higher false‑positive rates (claiming a problem that wasn’t real), often due to misreading website responses.

- Tasks that need clicking and interacting with graphical websites (GUI), like using web consoles, where humans did much better.

- Humans and ARTEMIS worked similarly overall: scan, pick targets, probe, exploit, repeat. But ARTEMIS was better at multitasking—launching multiple sub‑agents when it spotted something interesting.

Extra insights:

- When the team gave ARTEMIS hints (like the host name or the type of flaw), it could find specific missed vulnerabilities, showing the AI had the technical skill but sometimes missed the “pattern” in the noise.

- Cost tracked over longer runs showed ARTEMIS can be cheaper at similar performance, especially the version using GPT‑5 for both manager and sub‑agents.

Why does this matter?

This paper shows AI can already compete with human professionals in real, messy environments—not just in simplified “capture‑the‑flag” challenges. That has big implications:

- For defenders: AI agents like ARTEMIS could help run ongoing checks, find issues faster, and reduce costs, especially for large organizations.

- For safety: Because these systems are powerful, they need guardrails and monitoring. They can make mistakes, especially without a human to confirm critical actions.

- For future AI tools: Improving AI’s ability to use computers like a person (better GUI interaction) and reducing false alarms will unlock even more value.

Key takeaways you can remember

- AI can discover serious security problems in real networks, often at lower cost.

- ARTEMIS, a team‑based AI system, matched top human skills and came in second overall.

- AI is great at scanning and multitasking but weaker at point‑and‑click web tasks and sometimes overconfident.

- Using AI for defense will likely become common, but it still benefits from human review.

Final thoughts and impact

The team open‑sourced ARTEMIS so defenders can use and paper it. While the test was realistic, there were limits: shorter time than a typical pen‑test, fewer participants, and a friendly IT team that knew a test was happening. Even so, the results suggest a future where AI and humans work together—AI doing fast, broad checks and humans focusing on tricky parts—to make systems safer, cheaper, and more secure.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, consolidated list of concrete gaps and open questions that remain unresolved and could guide future research.

- External validity: results come from a single university network; evaluate across diverse environments (Windows/AD-heavy enterprises, cloud-first orgs, ICS/OT/SCADA, mobile, air-gapped, highly segmented networks).

- Defensive realism: blue team awareness and manual approvals removed real detection/response; measure agent/human performance under active EDR/SIEM/IDS, automated blocking, rate limiting, and SOC workflows.

- Time horizon: capped to 10 hours of active engagement; paper multi-week engagements to test long-horizon planning, persistence, opsec, and session resumption at scale.

- Sample size and selection: only 10 professionals with potential selection and incentive biases; increase N, diversify expertise, randomize starting conditions, and power analyses for hypothesis testing.

- Prior knowledge confounds: adjust for pre-engagement reconnaissance (e.g., P1) and baseline familiarity to ensure fair comparisons and isolate agent uplift.

- Unknown ground truth: lack of a comprehensive vulnerability ground truth prevents recall estimation; seed environments with hidden, labeled vulns to measure precision/recall and missed criticals.

- Scoring framework validity: custom complexity/criticality metric not validated; assess inter-rater reliability, sensitivity to weightings, and compare against alternative metrics (e.g., time-to-first-critical, exploit reliability, blast radius).

- Component ablations for ARTEMIS: quantify contributions of dynamic prompt generation, triage, session summarization, concurrency limits, and scheduling to overall performance and cost.

- Model variance and non-determinism: no repeated trials or CIs; run multiple seeds, report confidence intervals, and control temperatures/top‑p to separate scaffold uplift from sampling variance and model drift.

- Baseline fairness: some scaffolds received different inputs (Incalmo/MAPTA scope-only) and exhibited refusals; normalize instructions, tool access, and safety settings to ensure equitable comparisons.

- GUI interaction deficit: agents struggled with GUI-centric tasks (e.g., TinyPilot); integrate and evaluate headless browser automation (Playwright/Selenium), RDP/VNC control, and computer-use agents, then measure impact.

- False-positive (FP) behavior: only qualitative FP observations; build a taxonomy of FP causes (e.g., misread redirects), quantify reviewer time cost, and add FP-reduction strategies (negative controls, confirmation flows).

- Safety and autonomy: runs were human-supervised; test autonomous safety guardrails (scope control, rate limits, kill switches), and robustness to prompt injection, malicious banners, honeypots, and deception.

- Network impact: scanning risks and service degradation not quantified; instrument network to measure traffic load, DoS risk, and implement/assess auto back-off and politeness policies.

- Depth of post-exploitation: limited analysis of privilege escalation, lateral movement chains, persistence, and exfiltration; define chain-length and dwell-time metrics and evaluate progression quality.

- Detection evasion trade-offs: no measurement of agent stealth; quantify alert rates, signature triggers, and the speed–stealth trade-off under realistic SOC thresholds.

- Horizontal scaling: parallelism demonstrated on a single agent instance; paper fleet-level scaling (dozens/hundreds of agents), task deconfliction, shared-state consistency, and network strain.

- Human–agent teaming: hybrid workflows (copilot/oversight) were excluded; measure uplift, handoff protocols, explainability requirements, and UI/UX that reduce oversight burden.

- Environment archetypes: assess performance in Windows/AD-dominant domains, Kerberos/NTLM pivoting, cloud control planes (IAM misconfig, metadata services), zero-trust, NAC, and strict firewalling.

- Credential scenarios: evaluate seeded stolen creds, password policies, account lockouts, and adaptive throttling to emulate real credential-based intrusion patterns.

- Cost realism: include infra, monitoring, FP triage labor, cloud egress, vendor/tool licenses, and incident risk; report cost per valid and severity-weighted finding and total reviewer-hours saved/consumed.

- Reproducibility: live targets limit repeatability and model updates cause drift; release sanitized replicas, deterministic configs, seeds, and consider open-weight model baselines for stable comparisons.

- Policy/refusal handling: document how scaffold navigates model safety policies and refusal modes; quantify reliability across vendors and safety settings without encouraging unsafe bypass behavior.

- Tooling coverage: assess agent competence beyond scanners—custom exploit dev, exploit stability, patch verifiability, and remediation quality; measure exploit reproducibility across hosts/versions.

- Memory and long-horizon cognition: quantify summarization fidelity, context loss, and forgetting across sessions; evaluate memory architectures and memory QA to prevent trajectory drift.

- Prioritization heuristics: agents often submit quickly and move on; paper value-of-information planning, vulnerability priors, and host-centric dwell policies to uncover deeper chained exploits.

- Adversarial environments: test robustness against deceptive services, poisoned headers, throttled/latent networks, CAPTCHAs, and tarpits; define resilience metrics.

- Remediation impact: measure time-to-patch, fix correctness, regression risk, and coordination overhead with IT to link findings to realized security improvements.

- Ethical risk management: quantify misuse risks from open-sourcing, evaluate access controls and rate-limits, and paper deployment governance in enterprises.

- Benchmark alignment: correlate live-environment outcomes with CTF/CVE benchmarks; propose benchmark tasks that capture live constraints (noise, scope, rate limiting, multi-host chaining).

- Vantage point effects: test internal vs external footholds, VPN vs on-prem vantage, IP reputation effects, and egress controls on exploitability and enumeration efficacy.

- Starting privileges: all accounts had student-level Kerberos access; evaluate zero-credential external attacker, compromised admin, and insider threat baselines.

- Telemetry and provenance: strengthen instrumentation (SIEM integration, host EDR logs) and release privacy-preserving telemetry schemas for community replication and meta-analysis.

- Model lifecycle: evaluate sensitivity to vendor updates, implement snapshotting/version pinning, and schedule periodic re-evaluations with change-point tracking.

Glossary

- ARTEMIS: A multi-agent AI penetration testing framework (Automated Red Teaming Engine with Multi-agent Intelligent Supervision) designed for long-horizon offensive security tasks. "ARTEMIS is a multi-agent framework featuring dynamic prompt generation, arbitrary sub-agents, and automatic vulnerability triaging."

- bug bounty programs: Industry programs that pay researchers to find and responsibly disclose security vulnerabilities, often with higher rewards for more severe issues. "Mirroring the exponential reward structures found in industry bug bounty programs, where critical vulnerabilities receive disproportionately higher payouts, our scoring framework applies enhanced weighting to more severe findings to reflect their greater business risk:"

- CIA triad: The core security principles of confidentiality, integrity, and availability that guide risk assessment and mitigation. "confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) must be carefully considered."

- CORS: Cross-Origin Resource Sharing, a browser mechanism controlling which origins can interact with resources; misconfigurations can lead to security issues. "CORS wildcard, cookie flags"

- Credential dumping: Post-exploitation technique to extract stored credentials from systems. "Post-exploitation involved accessing sensitive files on Linux systems and credential dumping on Windows systems (T1003)."

- Credential harvesting: Collecting credentials (e.g., via network interception or phishing) to gain unauthorized access. "Several participants attempted network-based credential harvesting to intercept authentication attempts in Windows environments (T1557)."

- CTF: Capture the Flag, competitive security challenges used to benchmark offensive capabilities. "CTF suites such as Cybench \citep{zhang2025cybenchframeworkevaluatingcybersecurity} and NYU CTF Bench \citep{shao2025nyuctfbenchscalable} use metrics including first solve time (FST) and overall team score to establish human baselines,"

- CVEs: Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures, standardized identifiers for publicly known security flaws. "and reproduction of public vulnerabilities (CVEs)"

- DDOS: Distributed Denial-of-Service, attacks that overwhelm services to degrade availability. "malicious distributed denial-of-service attacks (DDOS, T1498 \ref{sec:mitre-attack})"

- Endpoint detection and response: Security tools that monitor endpoints to detect, investigate, and respond to threats. "sophisticated endpoint detection and response software"

- Exfiltration: Unauthorized extraction of data from a system or network. "the creation and execution of exploits may lead to the exfiltration of data, adversely affecting confidentiality."

- gobuster: A tool for brute-forcing web directories and files to aid reconnaissance. "gobuster for web directory brute-forcing"

- IDRAC: Integrated Dell Remote Access Controller, a remote server management interface that can have exploitable vulnerabilities. "The same CLI limitations that hurt ARTEMIS on TinyPilot helped it find this unique IDRAC vulnerability."

- Intrusion detection systems: Tools that monitor networks/systems for malicious activity or policy violations. "Additional controls such as intrusion detection systems, sophisticated endpoint detection and response software, centralized logging, and malware protection are required for moderate and high-risk systems."

- IRB: Institutional Review Board, an ethics committee that reviews research involving human participants. "Our study was conducted with IRB approval."

- Kali Linux: A Linux distribution tailored for penetration testing and ethical hacking. "running the Kali Linux operating system, which is an ethical hacking Linux distribution."

- Kerberos: A network authentication protocol using tickets to securely verify user identities. "Authentication within the network is managed through a Linux-based Kerberos system,"

- kill-chain: A model describing stages of a cyber attack from reconnaissance to actions on objectives. "Some followed structured kill-chain progressions with careful documentation,"

- Lateral movement: Moving from one compromised system to others within a network to expand access. "These exploits facilitated lateral movement (TA0008),"

- LDAP: Lightweight Directory Access Protocol, used for directory services like authentication. "we observed note a vulnerable LDAP server that other participants reported,"

- masscan: A high-speed network port scanner for large-scale reconnaissance. "network scanning using nmap, rustscan, and masscan to map in-scope subnets and identify active services (T1046)."

- MITRE ATT&CK: A knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques used to classify and map attack behavior. "we adopted the MITRE ATT{paper_content}CK framework."

- nmap: A widely used network mapper and port scanner for reconnaissance. "network scanning using nmap, rustscan, and masscan to map in-scope subnets and identify active services (T1046)."

- nuclei: A template-based vulnerability scanner for fast, automated detection. "Participants then expanded reconnaissance using nuclei for vulnerability scanning,"

- pass@1: An evaluation metric indicating success on the first attempt. "Whether the agent found the target vulnerability (green) or not (red) for pass@1, with total number of submissions in parentheses."

- Privilege escalation: Gaining higher-level permissions on a system after initial access. "with discovered credentials used for privilege escalation where possible (T1021.004)."

- Qualys: A commercial platform for vulnerability management and compliance. "monthly vulnerability management via Qualys with remediation timelines based on severity,"

- Remote code execution (RCE): The ability to run arbitrary code on a target system remotely. "While 80\% of participants found a remote code execution vulnerability on a Windows machine accessible via TinyPilot,"

- rustscan: A fast port scanner that leverages Rust’s performance. "network scanning using nmap, rustscan, and masscan to map in-scope subnets and identify active services (T1046)."

- SIEM systems: Security Information and Event Management platforms for centralized log analysis and alerting. "extend our logging framework to integrate defensive tools such as SIEM systems."

- SQL injection: A web attack that injects malicious SQL into inputs to manipulate backend databases. "Other techniques such as SQL injection (T1190, \ref{sec:mitre-attack}) can lead to lost data by mutating data or dropping tables, adversely affecting integrity."

- sqlmap: A tool that automates detection and exploitation of SQL injection vulnerabilities. "They gained initial access via SQL injection (sqlmap),"

- Stored XSS: A cross-site scripting variant where the payload is stored on the server and served to users. "Stored XSS in WebDB Person Editor Title Field: Improper sanitization allows XSS when viewing a person's profile (T1189)."

- TinyPilot: A KVM-over-IP device with a web interface that can expose remote console access. "Unauthenticated Remote Console Access via TinyPilot Web Interface: Gives RCE on a series of Windows machines running TinyPilot (T1190)."

- TTPs: Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures used by adversaries; a framework for analyzing attack behavior. "We analyze the TTPs of both human and agent participants to establish foundations for realistic AI cybersecurity evaluations."

- Vulnerability triaging: The process of validating, prioritizing, and de-duplicating vulnerability reports. "automatic vulnerability triaging."

- Vulnerability Disclosure Policy (VDP): A policy defining how vulnerabilities should be reported and protections for researchers. "the university's Vulnerability Disclosure Policy (VDP) defines safe-harbor protections and explicitly prohibits excessively disruptive or destructive actions,"

- Zero-days: Previously unknown vulnerabilities with no available patches. "teams of autonomous agents working in tandem that can conduct multi-host network attacks and exploit zero-days"

Practical Applications

Below is an overview of practical, real‑world applications that follow from the paper’s findings and the ARTEMIS framework (multi‑agent supervision, dynamic prompt generation, long‑horizon sessioning, and automatic vulnerability triage). Each item identifies sectors, potential tools/workflows, and key dependencies or assumptions that affect feasibility.

Immediate Applications

- Agent‑augmented penetration testing for enterprises and MSSPs (sectors: software, finance, healthcare, education, energy)

- What: Use ARTEMIS as a “junior tester” to conduct systematic enumeration and parallel probing, with human professionals guiding pivots, validating high‑impact chains, and handling GUI‑heavy steps.

- Tools/workflows: ARTEMIS open-source scaffold; sub‑agent swarm for recon/exploitation; triage module to filter duplicates/false positives; engagement runbooks aligning with MITRE ATT&CK; handoff to human analyst at predefined gates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to capable LLMs (e.g., GPT‑5, Claude); organizational VDP/safe‑harbor; guardrails and live oversight as in the paper; model policies that do not refuse lawful offensive tasks; network scanning change windows.

- Continuous attack surface management and “always‑on red teaming” (sectors: software, finance, healthcare, education)

- What: Scheduled agent runs (e.g., weekly) across subnets to proactively discover misconfigurations and exploitable paths in large, heterogeneous networks (~thousands of hosts).

- Tools/workflows: ARTEMIS sessioning for long‑horizon operation; SIEM/EDR/SOAR integration for alerting and ticket creation; Qualys/Nmap/Nuclei toolchain orchestration via sub‑agents.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Low‑impact scanning profiles approved by IT; robust network monitoring; acceptance of higher false‑positive rates versus humans; model cost budgeting.

- Bug bounty triage and verification (sectors: software platforms, fintech, consumer web)

- What: Use the triage module to reproducibly verify community‑submitted reports, reduce duplicates, and auto‑generate replication steps.

- Tools/workflows: ARTEMIS triage module; the paper’s scoring framework (technical complexity + weighted severity) to prioritize payouts/SLAs; automated repro in isolated sandboxes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sandboxed targets; clear rules on data handling; model reliability and determinism for reproducible trials.

- SOC emulation and purple‑team exercises (sectors: finance, healthcare, defense/critical infrastructure, education)

- What: Agents simulate adversary TTPs mapped to MITRE ATT&CK to stress‑test detection and incident response, while defenders observe and harden controls.

- Tools/workflows: ATT&CK‑aligned playbooks; controlled intensity profiles (enumeration only vs. exploitation); dual‑monitoring/kill‑switch procedures used in the paper.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Pre‑approved scope and containment; deconfliction with blue team tools to avoid service degradation.

- Cost‑effective testing for SMBs and resource‑constrained orgs (sectors: SMB across all verticals)

- What: Deploy the lower‑cost ARTEMIS variant (∼$18/hour in the paper) as a managed service to deliver baseline pen‑test coverage between annual audits.

- Tools/workflows: Managed “agent‑as‑a‑service” offering; predefined scopes and maintenance windows; automated report generation with remediation suggestions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal authorization; simplified network topologies; shared responsibility for patch verification.

- Vulnerability reproduction in PSIRT/DevSecOps (sectors: software)

- What: Rapid repro of reported issues (including SQLi, XSS, misconfigurations) using targeted hints, as demonstrated by the elicitation trials.

- Tools/workflows: “Hint‑driven repro” pipelines; safe staging mirrors; automatic PRs or tickets linking repro steps and impact analysis.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Non‑production mirrors; strict governance on secrets and data; model access controls.

- Education and academic research labs (sectors: education)

- What: Incorporate the open‑source scaffold and scoring framework into practical courses, red‑team/blue‑team classes, and empirical agent evaluation research.

- Tools/workflows: Curriculum modules; evaluation rubrics (technical complexity + severity weighting); shared datasets/logs from runs; standardized MITRE mapping.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Faculty oversight; isolated lab networks; ethics instruction; IRB‑style safeguards for studies.

- Policy‑ready safeguards for live agent testing (sectors: public sector, regulated industries)

- What: Adopt the paper’s dual‑monitoring model, VDP alignment, and halt procedures as “how‑to” guidance for safe agent deployments in production.

- Tools/workflows: Oversight dashboards; audit trails of agent actions; scope enforcement and kill‑switches; pre‑authorization workflows.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational appetite for piloting AI agents; compliance review; vendor ToS/legal counsel alignment.

- CLI‑first assessment of legacy and headless systems (sectors: energy, manufacturing, telco, robotics/IoT)

- What: Leverage agents’ strong CLI capabilities to interrogate systems where modern browsers fail (e.g., outdated management consoles), as observed with IDRAC exploitation.

- Tools/workflows: Curl/OpenSSL‑based probes; protocol‑level enumeration; machine‑readable output parsing by sub‑agents.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strict change control for legacy assets; read‑only reconnaissance modes to avoid outages.

Long‑Term Applications

- Fully autonomous, continuous, enterprise red‑teaming (sectors: all)

- What: Near‑real‑time agents that enumerate, exploit, and validate impact at scale, with humans only for exception handling and high‑risk actions.

- Tools/workflows: Always‑on agent clusters; real‑time SIEM/SOAR feedback loops; auto‑suppression of known noise; staged exploitation policies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Significant reduction in false positives; hardened GUI/computer‑use capability; robust containment; regulator buy‑in.

- Computer‑use agents for GUI/web workflows (sectors: software, healthcare, finance, ICS HMI)

- What: Integrate advanced browser/desktop control (e.g., ACI/SWE‑agent‑style interfaces) so agents can handle login flows, RCE via web consoles, and multi‑step GUI tasks (a current ARTEMIS gap).

- Tools/workflows: Headless browsers with human‑like interaction; secure credential brokers; session recording with redaction for audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Mature human‑computer interaction agents; privacy‑preserving telemetry; robust anti‑misclick safeguards.

- Sector‑specific playbooks and digital twins (sectors: healthcare, energy, manufacturing, education)

- What: Tailored agent playbooks for EHR, medical devices, ICS/SCADA, and campus networks; use high‑fidelity replicas to test safely before production.

- Tools/workflows: Vendor‑provided environment clones; ICS/IoT protocol libraries; safety interlocks to prevent disruptive operations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Vendor partnerships; digital twin coverage; rigorous safety/ethics frameworks.

- Agent‑driven security compliance and control validation (sectors: finance, healthcare, public sector)

- What: Automate evidence collection and technical control tests for frameworks (e.g., ISO 27001, SOC 2, HIPAA), converting findings into audit‑ready artifacts.

- Tools/workflows: Control‑to‑probe mapping; signed execution logs; tamper‑evident attestation of findings; integration with GRC tools.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standardized mappings; auditor acceptance of agent‑generated evidence; chain‑of‑custody controls.

- Quantitative cyber risk scoring for insurance and regulators (sectors: insurance, public policy)

- What: Use the paper’s complexity/severity scoring to produce standardized, repeatable risk scores across organizations for underwriting and supervisory oversight.

- Tools/workflows: Calibrated scoring pipelines; cross‑org benchmarks; longitudinal metrics for security posture improvement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community consensus on scoring; reproducible environments; transparent methodologies.

- Workforce transformation and certification (sectors: industry, education, policy)

- What: Standardize “human‑in‑the‑loop agent operator” roles, certifications, and curricula that teach supervising and validating agent findings.

- Tools/workflows: Operator dashboards; escalation SOPs; agent behavior analytics; training datasets from recorded engagements.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Professional bodies and standards; liability frameworks; training availability.

- Regulatory standards for offensive AI deployment (sectors: policy, regulated industries)

- What: Formalize safe‑deployment requirements (logging, kill‑switches, scope enforcement, disclosure policies), informed by this paper’s safeguards.

- Tools/workflows: Compliance checklists; periodic capability/risk evaluations; third‑party attestations; red‑team AI reporting.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi‑stakeholder consensus; harmonization with existing cyber regulations.

- Autonomous purple‑team ecosystems (sectors: all)

- What: Co‑evolving attacker/defender agents for continuous resilience testing—red agents probe, blue agents detect and mitigate in near‑real‑time.

- Tools/workflows: Closed‑loop simulation environments; shared knowledge bases; measured improvements via ATT&CK coverage metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Safe cohabitation in production or robust digital twins; clear guardrails to avoid destabilizing systems.

- AI‑enhanced bug bounty platforms and competitions (sectors: software, public interest)

- What: Platforms where human researchers collaborate with agents for larger scopes, faster triage, and reproducible exploitation; standardized leaderboards using the paper’s scoring.

- Tools/workflows: Agent sandboxes for contestants; automated verification harnesses; payout models tied to calibrated risk scores.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Dual‑use risk governance; platform policies; reproducibility infrastructure.

- Tooling innovations from the scaffold (sectors: cybersecurity software)

- What: Commercial/open products derived from ARTEMIS components—multi‑agent orchestration layers, dynamic prompt/task generation, vulnerability triagers, session memory managers, model‑ensemble supervisors, and cost optimizers.

- Tools/workflows: SDKs/APIs for agent building; plug‑ins for SIEM/SOAR; model routing based on task type and price/performance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable model APIs; vendor neutrality; strong observability and RBAC.

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- Current limitations (higher false‑positive rates, weak GUI interaction/refusal in some model/tooling setups) favor “human‑in‑the‑loop” deployment now.

- Legal/ethical prerequisites (VDP/safe‑harbor, scope control, continuous monitoring, termination authority) are essential to replicate the paper’s safe operation.

- Cost curves and model availability (including policy constraints on offensive uses) will determine scalability and accessibility, especially for SMBs and academic programs.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.