Multi-view Pyramid Transformer: Look Coarser to See Broader (2512.07806v1)

Abstract: We propose Multi-view Pyramid Transformer (MVP), a scalable multi-view transformer architecture that directly reconstructs large 3D scenes from tens to hundreds of images in a single forward pass. Drawing on the idea of ``looking broader to see the whole, looking finer to see the details," MVP is built on two core design principles: 1) a local-to-global inter-view hierarchy that gradually broadens the model's perspective from local views to groups and ultimately the full scene, and 2) a fine-to-coarse intra-view hierarchy that starts from detailed spatial representations and progressively aggregates them into compact, information-dense tokens. This dual hierarchy achieves both computational efficiency and representational richness, enabling fast reconstruction of large and complex scenes. We validate MVP on diverse datasets and show that, when coupled with 3D Gaussian Splatting as the underlying 3D representation, it achieves state-of-the-art generalizable reconstruction quality while maintaining high efficiency and scalability across a wide range of view configurations.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Explaining “Multi-view Pyramid Transformer: Look Coarser to See Broader”

1. What is this paper about?

This paper introduces a new AI model called the Multi-view Pyramid Transformer (MVP). Its job is to quickly build a 3D model of a scene using lots of photos taken from different viewpoints. The big idea is simple: look broadly to understand the whole scene, and look closely to capture fine details. MVP is designed to do both efficiently, even when you give it dozens or hundreds of images.

2. What questions were they trying to answer?

The researchers wanted to solve two main problems:

- How can we use many high-resolution photos to reconstruct a 3D scene without the computer running out of memory or slowing down too much?

- How can we keep the 3D model accurate—both globally (the whole scene makes sense) and locally (small details look right)—as the number of input images gets bigger?

3. How did they do it?

Think of building a 3D scene like solving a giant puzzle:

- Each photo gives you many small “pieces” (called tokens) that represent patches of the image.

- A transformer (a type of AI model) helps the puzzle pieces from different images “pay attention” to each other to figure out what matches across views.

The challenge: if you have many photos, the number of puzzle pieces explodes, and the model becomes very slow.

MVP solves this with two smart steps working together:

- Inter-view hierarchy (across photos): The model first looks within each single photo, then within small groups of photos, and finally across all photos. This is like organizing your puzzle by small sections before assembling the whole thing.

- Intra-view hierarchy (inside each photo): The model starts with fine details and gradually merges them into larger, simpler chunks. This is like first examining the tiny textures (blades of grass), then zooming out to bigger shapes (the lawn), to understand the larger scene.

These two hierarchies keep the model fast and stable:

- It avoids “attention overload” where the AI tries to look at everything at once and gets confused.

- It captures both details and the big picture.

To turn the learned features into a final 3D scene, MVP uses:

- Pyramidal Feature Aggregation: imagine combining information from different zoom levels—fine details plus coarse context—to get the best of both worlds.

- 3D Gaussian Splatting: think of painting the 3D world with many tiny, soft blobs (Gaussians) that can glow and change with viewing angle. When rendered, these blobs create realistic images from new viewpoints.

Training works like this: the model predicts a 3D scene from input photos, renders what another camera would see, and compares that to a real photo. If the rendered image looks wrong, the model adjusts to improve next time.

4. What did they find, and why is it important?

MVP reconstructs large scenes fast and accurately, even with many input photos.

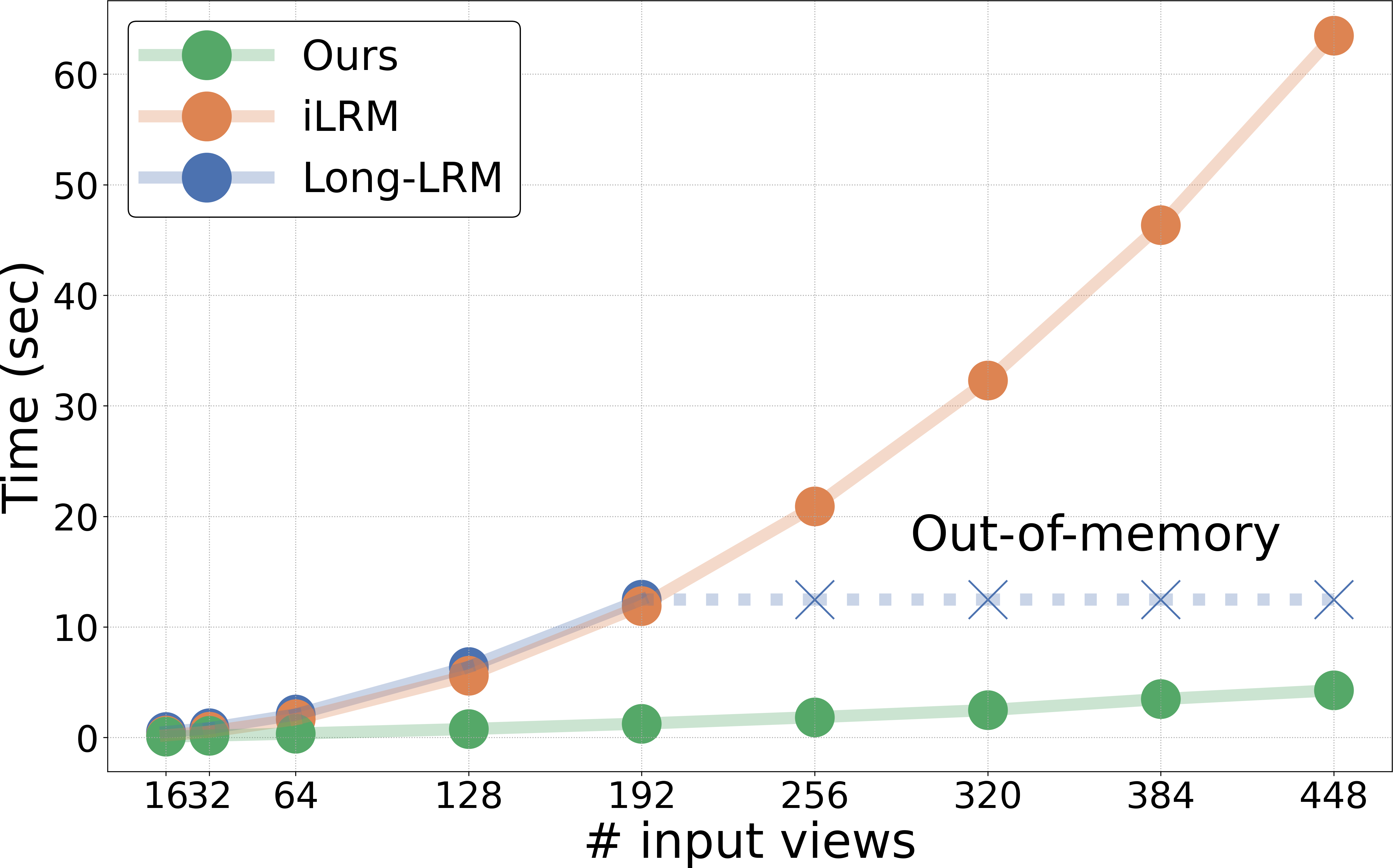

- Speed: It processes around 16–256 images in roughly 0.1–2.0 seconds on a high-end GPU. That’s far faster than methods that slowly optimize for minutes.

- Quality: It produces sharper and more realistic images when you look at the scene from new angles. In standard metrics:

- PSNR and SSIM (higher is better) improved compared to other fast methods.

- LPIPS (lower is better; measures perception) also improved.

- Scalability: It keeps working well as you give it more images, while some competitors slow down a lot or run out of memory.

- Stability: As the number of photos grows, MVP avoids the common problem where attention gets “diluted” and stops learning good matches.

In simple terms: MVP is both fast and good. It often matches or beats slower, optimization-based methods in quality, and it clearly beats other fast “single-pass” methods in both speed and accuracy.

5. Why does this matter? What could it impact?

This kind of model can change how we build 3D worlds from photos:

- Faster 3D capture for AR/VR, filmmaking, games, and virtual tours.

- Better scene understanding for robots and drones navigating real environments.

- More efficient mapping and reconstruction for architecture or cultural heritage.

Because MVP is designed to scale and fuse details and global context smoothly, it opens the door to handling:

- Dynamic scenes (moving objects) by adding time as another dimension.

- More accurate geometry by training with extra 3D supervision data.

Overall, MVP shows a practical path to high-quality, large-scale 3D reconstruction that’s both fast and reliable—making complex 3D modeling more accessible across many fields.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, phrased to guide follow-up research and ablations:

- Reliance on known, accurate camera poses: MVP requires posed inputs (Plücker rays, PRoPE), but robustness to noisy/biased intrinsics/extrinsics and tolerance to COLMAP failures are not evaluated; no joint camera estimation or pose refinement is supported.

- Unordered or non-temporal input sets: View groups are formed by index-locality (consecutive frames), assuming a trajectory-like ordering; behavior with unordered Internet photo collections or multi-camera capture is untested.

- Fixed, hand-designed grouping: Group size and composition (e.g., M=4) are fixed and heuristic; there is no exploration of adaptive/learned grouping based on geometric overlap, baseline, visibility, or content.

- Sensitivity to group size and schedule: The trade-offs between group size, token resolution, and model depth are not characterized; no scaling-law analysis links group-wise/global coverage to accuracy, stability, and compute.

- No learning-based group assignment: The paper does not explore attention routing that dynamically selects neighbors (e.g., via similarity/pose-aware KNN) or differentiable grouping policies.

- Assumed perfect camera geometry in encodings: PRoPE and Plücker rays assume undistorted, metric camera models; sensitivity to lens distortion or rolling shutter is not assessed.

- Intra-view downsampling method is fixed: Token reduction uses a single convolution per stage; content-aware token merging/selection (e.g., ToMe, clustering, token pruning/skipping) is not evaluated for efficiency vs. fidelity.

- Potential aliasing and detail loss: The effect of the chosen spatial downsampling on thin structures, high-frequency textures, and aliasing is not studied; alternative anti-aliased merging methods are untested.

- Attention-dilution mitigation lacks theory: Claims about avoiding attention dilution under long contexts are empirical; no formal analysis of attention distributions, gradient stability, or convergence is provided.

- Limited exploration of attention patterns: Only frame-wise → group-wise → global is examined; reverse/bi-directional hierarchies are minimally tested, and cross-stage attention variants (e.g., cross-scale attention) are not explored.

- Scalability beyond 256 views is unknown: Performance, memory, and stability at >256 views or very long contexts (e.g., multi-thousand images) are not evaluated; memory scaling and throughput under sharding/pipelining remain open.

- Memory footprint not reported: Detailed peak GPU memory across view counts and resolutions is missing; practitioners cannot assess deployment constraints or memory-compute trade-offs.

- No visibility or occlusion modeling: Group/global attention ignores geometric visibility or depth ordering; explicit visibility-aware attention or epipolar constraints are not integrated or ablated.

- Supervision is view-synthesis only: Geometry quality is not validated with 3D metrics (e.g., depth error, point/mesh Chamfer, normal consistency); it is unclear how well geometry is reconstructed vs. photo-consistency exploited.

- No geometry-supervised training variants: The impact of adding supervision from depth/point maps (e.g., DUSt3R/triangulated supervision) is untested despite being suggested in discussion.

- Static-scene assumption: Dynamic/4D scenes and temporal consistency are not handled; there is no architecture or training recipe for motion, non-rigid deformations, or rolling-shutter artifacts.

- Per-pixel Gaussian representation is fixed: The model predicts one Gaussian per pixel at input resolution; variable-count, adaptive placement/pruning, or learned densification/compactness of Gaussians are not explored.

- View-dependent opacity (SH) may cause geometry inconsistency: Using spherical harmonics for opacity can produce view-dependent density; the proposed regularizer is not deeply analyzed, and residual artifacts are not quantified.

- Rendering cost and quality not profiled: While reconstruction-time is reported, the runtime and quality of real-time rendering from the predicted Gaussians across view counts are not measured or compared.

- Decoder capacity is minimal: A single linear head is used; the effect of richer decoders (e.g., small CNN/Transformer heads, per-scale decoders) on fidelity and efficiency is not studied.

- Lack of ablations for camera encoding: The impact of PRoPE vs. alternative camera positional encodings (e.g., absolute vs. relative, learned embeddings, epipolar-aware encodings) is not reported.

- Training objective details are incomplete: The loss equations in the paper are partially missing/garbled (e.g., exact form of L_img, R_α), and SH orders, quaternion normalization, and other implementation specifics are not fully specified—hindering reproducibility.

- Heavy compute requirements: Training uses 32× H100 GPUs across three stages for ~9 days; there is no paper on data/compute efficiency, smaller models, or distillation for practical adoption.

- Fairness of comparisons: Baselines are trained with fixed 32-view inputs while MVP is trained with mixed view counts and a multi-stage schedule; a matched training regime for baselines or an ablation of MVP without mixed-count training is not provided.

- Domain generalization is limited: Generalization is only shown on Tanks and Temples and Mip-NeRF360; robustness to in-the-wild smartphone videos, extreme lighting, low-texture, and specular scenes is not characterized.

- Robustness to photometric variation: There is no analysis under exposure changes, color shifts, motion blur, or noise; the model’s tolerance to photometric inconsistencies is unknown.

- Handling unordered large Internet photo sets: The method is not evaluated on datasets like MegaDepth/Phototourism with diverse, sparse, and inconsistent views.

- Cross-task transferability: Although the architecture is claimed to be general, it is not validated on other multi-view tasks (e.g., depth/normal prediction, point map, pose estimation) to demonstrate representational reuse.

- Parameter count and model size are not disclosed: Model size vs. performance, and the contribution of each stage to total parameters, are not reported, impeding replication and scaling studies.

- Energy and environmental cost: Training/inference energy use and CO₂ footprint are not reported; no discussion of efficiency targets or carbon-aware training strategies is provided.

Glossary

- 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS): An explicit 3D scene representation that uses many Gaussian primitives for fast radiance field rendering and reconstruction. "3D Gaussian Splatting as the underlying 3D representation"

- Alternating-Attention (AA) module: A transformer pattern that alternates attention operations across different scopes (e.g., per-frame and global). "Alternating-Attention (AA) module~\cite{wang2025vggt}"

- Alternative Attention: An efficient attention variant used to process multiple views with reduced computational cost. "Alternative Attention~\cite{wang2025vggt}"

- Attention dilution: The effect where attention weights spread too thin over a very long context, weakening correspondence learning. "avoiding attention dilution"

- Bidirectional Mamba: A linear-time state-space sequence model used to improve efficiency in long-context processing. "bidirectional Mamba~\cite{mamba2} blocks"

- COLMAP: A Structure-from-Motion and Multi-View Stereo pipeline used to estimate accurate camera poses from image sequences. "Each scene is processed using COLMAP~\cite{schoenberger2016sfm, schoenberger2016mvs} to obtain accurate camera poses"

- DUSt3R: A multi-view transformer-based method that learns 3D geometry directly from multi-view imagery. "DUSt3R~\cite{wang2024dust3r}"

- Dual Attention Hierarchy: The paper’s core hierarchical design combining inter-view (local-to-global) and intra-view (fine-to-coarse) attentions. "Dual Attention Hierarchy"

- FlashAttention3: An optimized attention kernel that accelerates transformer inference and reduces memory usage. "FlashAttention3~\cite{shah2024flashattention}"

- Frame-wise attention: Self-attention restricted to tokens within a single input image (frame). "frame-wise attention"

- Global self-attention: All-to-all attention over every token across views, with quadratic complexity in sequence length. "global self-attention"

- Group-wise self-attention: Self-attention performed within predefined groups of views to balance global consistency and efficiency. "group-wise self-attention"

- iLRM: A large reconstruction model that uses a compact scene representation to enable full attention across views. "iLRM~\cite{kang2025ilrm}"

- Long-LRM: A large reconstruction model integrating transformer blocks with bidirectional Mamba for efficiency. "Long-LRM~\cite{ziwen2025longlrm}"

- LPIPS: Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity, a perceptual image quality metric correlating with human judgment. "LPIPS "

- MSE loss: Mean Squared Error loss used to measure pixel-wise differences between rendered and ground-truth images. "MSE loss"

- Multi-view transformers: Transformer architectures designed to reason over sequences of images from multiple viewpoints. "Multi-view transformers"

- Novel view synthesis: Generating photorealistic images of a scene from unseen camera viewpoints. "novel view synthesis~\cite{flynn2024quark, jin2025lvsm}"

- Out-of-memory (OOM): A failure mode where GPU memory is exceeded during inference or training. "OOM (GPU memory limit exceeded, 80\,GB)"

- Patchify: Converting images into non-overlapping patches that serve as tokens for transformer processing. "patchified into non-overlapping patches"

- Plücker ray map: A 9D per-pixel ray encoding using origin, direction, and their cross product to incorporate camera geometry. "9D Plücker ray map"

- PRoPE: A relative positional encoding scheme used to condition attention with camera geometry. "We also apply PRoPE~\cite{li2025prope} to encode cameras as relative positional signals,"

- PSNR: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio, an image fidelity metric measuring reconstruction quality. "PSNR "

- Pyramidal Feature Aggregation (PFA): A module that fuses multi-scale features from all stages via top-down refinement for dense prediction. "Pyramidal Feature Aggregation (PFA) module"

- Quaternion: A four-parameter representation of 3D rotation used to parameterize Gaussian primitives. "(quaternion)"

- Register tokens: Special tokens appended per view to stabilize training and provide view-level context in transformers. "register tokens"

- SSIM: Structural Similarity Index Measure, an image quality metric assessing structural fidelity. "SSIM "

- Spherical harmonic coefficients: Coefficients that model view-dependent appearance (color/opacity) as functions over directions. "predict spherical harmonic coefficients for both view-dependent color and opacity"

- Swin Transformer: A hierarchical transformer with shifted windows that progressively reduces token resolution. "Swin Transformer~\cite{liu2021Swin, liu2022videoswintransformer}"

- Token embedding dimension: The dimensionality of token feature vectors within transformer layers. "The token embedding dimensions are set to 256, 512, and 1024"

- Token reduction: Downsampling or merging tokens to shorten sequences and enlarge receptive fields while increasing channels. "token reduction modules"

- View-dependent color and opacity: Appearance properties that vary with viewing direction, modeled via spherical harmonics. "view-dependent color and opacity"

- Zero-shot setting: Evaluation without training or fine-tuning on the target dataset or scenes. "under a zero-shot setting."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now using the MVP architecture and its demonstrated integration with feed-forward 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS), with known camera poses and existing rendering stacks.

- Industry (Construction, Real Estate, Digital Twins): Rapid site digitization and as-built capture for buildings and interiors from 32–256 photos in under ~0.1–2 seconds; pipeline: capture (phone or DSLR) → pose estimation (COLMAP, DUSt3R/VGGT) → MVP inference → 3DGS render/import (Viser, Blender/Unity/Unreal plugins); assumptions/dependencies: static scenes, adequate view coverage, known/estimated camera poses, 3DGS-compatible viewer/engine, GPU access (cloud or on-prem; times reported on H100).

- Industry (E-commerce): Fast turntable product digitization to create photoreal 3D viewable assets for online catalogs; workflow: multi-view product shots → MVP inference → 3DGS asset → web viewer; assumptions: controlled lighting, pose estimation per view, moderate compute.

- Media/Entertainment (Film/VFX): On-set environment capture for previsualization and blocking; workflow: panorama/multi-view sweep → MVP → immediate 3D reference without lengthy optimization; assumptions: static set segments, pose estimation, 3DGS viewer integration.

- VR/AR/Metaverse (Software): Real-time or near-real-time conversion of photo sets into navigable scenes; tools: MVP-based “Scan-to-Scene” plug-ins for Unity/Unreal; assumptions: static scenes, cloud GPU for high-res inference, export path to 3DGS or baked meshes.

- Cultural Heritage and Museums: Field-friendly digitization of artifacts and rooms where compute/time is limited; workflow: multi-view capture → MVP inference on portable workstation or cloud → 3DGS archive; assumptions: static subjects, pose estimation, permission and lighting constraints.

- Robotics and Simulation (Software/Robotics): Rapid environment model creation for simulation or planning (e.g., warehouse layouts); workflow: multi-camera capture → SLAM for poses → MVP → 3DGS scene for sim; assumptions: static environments, accurate poses from SLAM/VO, offboard GPU (edge or base station).

- Insurance and Claims (Finance): Fast property/interior condition documentation with photoreal 3D; workflow: agent capture → MVP → 3DGS in claim portal; assumptions: static scenes, capture guidelines, compliance with privacy regulations.

- AEC/BIM Quality Assurance (Construction): As-built vs. design verification by aligning MVP-generated splats with CAD/BIM; tools: alignment via Umeyama or ICP; assumptions: static scenes, pose estimation, tolerance calibration between splats and CAD.

- Academia (Computer Vision): A scalable baseline for long-context multi-view reasoning; use MVP to paper attention dilution vs. dual hierarchy benefits, ablate group size and token reduction; assumptions: access to datasets (DL3DV, Tanks & Temples, Mip-NeRF360), 3DGS renderer.

- Academia (Dataset Creation): Batch creation of photoreal novel views and reconstructions from existing datasets at scale to support benchmarking and annotation; assumptions: dataset licensing, known camera intrinsics/extrinsics, compute.

- Education (Teaching/Labs): Hands-on courses demonstrating multi-view reconstruction with hierarchical attention; lightweight variants at 256×256 (as shown on RE10K) for classroom exercises; assumptions: simplified hardware or cloud credits, curated sample scenes.

- Daily Life (Consumers): Cloud-backed room scanning via smartphone (4–32 images) to enable AR interior design and 3D previews; workflow: mobile app → upload views → MVP in cloud → 3D preview; assumptions: network connectivity, privacy/consent, pose estimation via phone sensors or cloud pipeline.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, or architectural extensions (e.g., dynamic scenes, pose-free inputs, mesh conversion, on-device deployment).

- Pose-Free Multi-View Reconstruction (Software/Robotics): End-to-end pipeline without known camera poses by integrating MVP with pose estimation (DUSt3R/VGGT) or learning joint pose+reconstruction; dependencies: robust joint training, failure handling for degenerate view geometry.

- Dynamic/4D Scene Reconstruction (Media/Robotics): Extend MVP’s dual hierarchy with explicit temporal modeling to reconstruct moving objects, crowds, or deforming scenes; dependencies: 4DGS or dynamic representations, occlusion handling, temporal consistency and memory management.

- Live Multi-Camera Analytics (Smart Cities/Security): Group-wise cross-camera reasoning for event detection and 3D situational awareness; tools: MVP variant with temporal stream fusion and camera network calibration; dependencies: real-time streaming, privacy/legal compliance, temporal attention design.

- On-Device/Edge Inference (Mobile/IoT): MVP-lite models for 256×256 feeds on consumer GPUs or NPUs (coarser patch sizes, reduced groups); dependencies: model compression, quantization, memory-aware attention, device-specific runtimes.

- CAD/Mesh Conversion (Construction/AEC): High-quality conversion of 3DGS outputs to watertight meshes suitable for CAD/BIM workflows; dependencies: reliable splat-to-mesh algorithms, geometric post-processing, material parameter recovery.

- Urban-Scale Digital Twins (Policy/Urban Planning/Energy): City-block reconstructions from drone or street-level captures with scalable grouping and batching; dependencies: robust view grouping strategies beyond index locality, distributed inference, data governance.

- Medical Imaging (Healthcare): Adapt MVP to multi-view endoscopy, X-ray, or ultrasound where multi-view geometry differs from consumer imagery; dependencies: domain-specific training, physics-informed priors, privacy and regulatory compliance.

- Autonomous Systems Pre-Deployment Mapping (Robotics): Fast map generation for route planning and simulation with frequent updates; dependencies: fusion with SLAM/HD-map layers, consistency across re-scans, compute constraints.

- Telepresence and Remote Collaboration (Software/Communication): Photoreal recon of meeting spaces for remote participants; dependencies: dynamic modeling, low-latency streaming, privacy filters.

- Sustainable Compute and Policy (Policy): Guidelines and best practices for low-energy, feed-forward photogrammetry replacing long optimization loops; dependencies: lifecycle assessments, procurement standards, audit of model bias/generalization.

- Disaster Response and Public Safety (Policy/Industry): Rapid 3D capture of damaged sites for assessment and coordination; dependencies: ruggedized capture workflows, standardized reporting formats, public data-sharing frameworks.

- Education-at-Scale (Education): MOOCs and labs offering cloud-hosted MVP sandboxes for learning multi-view geometry and attention design; dependencies: managed cloud cost, open datasets, simplified tooling.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Known camera poses or reliable pose estimation are critical for current MVP; integrating pose estimation raises complexity and failure modes.

- Static scene assumption; dynamic extensions require temporal modules and possibly new training regimes.

- Rendering stack compatibility (3DGS), and visualization tooling (e.g., Viser, Blender/Unity/Unreal integration).

- Compute availability: reported latencies are on H100 GPUs; consumer-grade performance will vary; cloud delivery can bridge gaps.

- Data coverage and quality: diverse viewpoints, sufficient overlap, controlled lighting for best results; reflective/translucent materials can challenge reconstruction.

- Domain generalization: fine-tuning may be needed for specialized domains (medical, industrial).

- Legal and ethical constraints: privacy in indoor captures, consent, data governance for public spaces.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.