Quantum machine learning -- lecture notes (2512.05151v1)

Abstract: Lecture notes on quantum machine learning for computer scientists.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is a friendly, step-by-step tour of quantum machine learning (QML). It explains:

- what QML is,

- the different ways classical (everyday) and quantum (tiny, weird physics) data and computers can work together,

- and how “probability” works in the classical world versus the quantum world.

It builds simple intuition using coins, lists of numbers, and geometric pictures before introducing the quantum versions (like vectors and matrices, qubits, and the Bloch sphere). The goal is to help you understand how quantum ideas might boost machine learning.

Key Objectives and Questions

The paper sets out to:

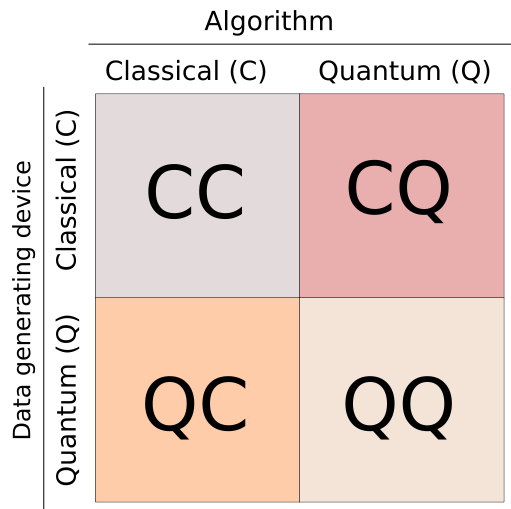

- Clarify the four main “pairings” in QML:

- CC: Classical data + Classical algorithms (today’s standard ML)

- CQ: Classical data + Quantum algorithms (use quantum circuits to speed up parts of ML)

- QC: Quantum data + Classical algorithms (use ML to help run and understand quantum experiments)

- QQ: Quantum data + Quantum algorithms (future possibilities like quantum cryptography)

- Build a bridge from classical probability (like chances in coin flips) to quantum probability (how qubits behave).

- Explain key ideas that show why quantum probability is richer than classical probability:

- Pure vs. mixed states

- Measurement and “collapse”

- Entropy (how uncertain you are)

- Entanglement (strong correlations that can’t happen classically)

Methods and Approach

The paper uses a “teaching by analogy” approach:

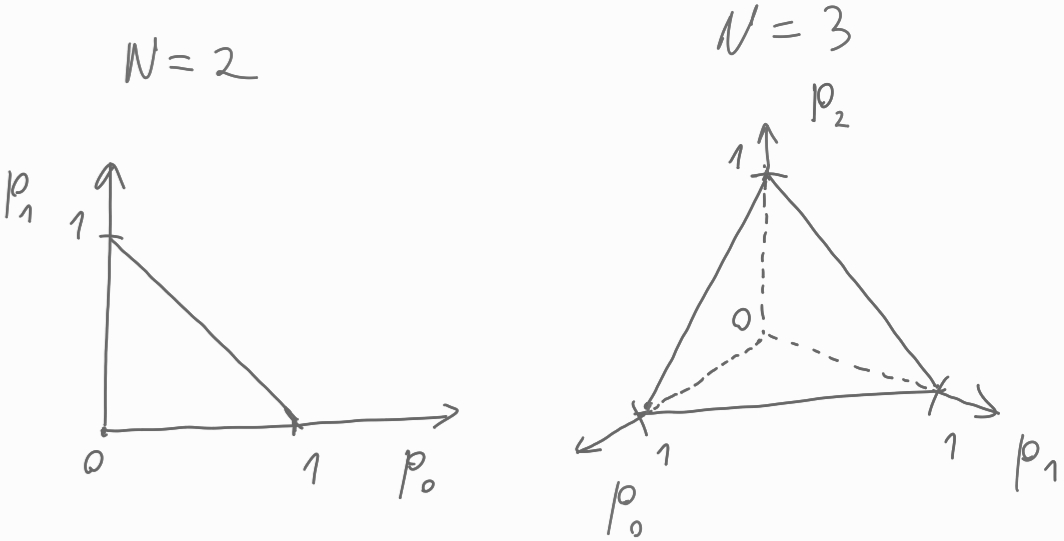

- Start with classical probability in everyday terms. Think of:

- A probability vector like a list of chances for different outcomes (e.g., a fair coin has ).

- Simple events (like heads or tails).

- How to update probabilities after you see an outcome (you “collapse” your belief).

- Geometric pictures: the “probability simplex” is the shape of all possible probability lists (for two outcomes, it’s a line; for three, a triangle).

- Useful tools:

- Shannon entropy: measures uncertainty (“how many yes/no questions do I need on average to find the answer?”).

- Relative entropy: measures how different two probability models are (helpful when your assumption is wrong).

- Fisher–Rao metric: a careful way to measure distance between probability distributions (helps make smarter learning steps).

- Then extend the same ideas to quantum probability:

- Replace probability lists with matrices called “density matrices.” These encode both probabilities and “phase” information (unique to quantum).

- A qubit (quantum bit) is a two-outcome system like a coin, but it can be in superpositions (a blend of possibilities) rather than just a simple probability mix.

- Show how measurements (using “projectors”) produce classical probabilities from a quantum state, and how the quantum state updates (“collapses”) after observation.

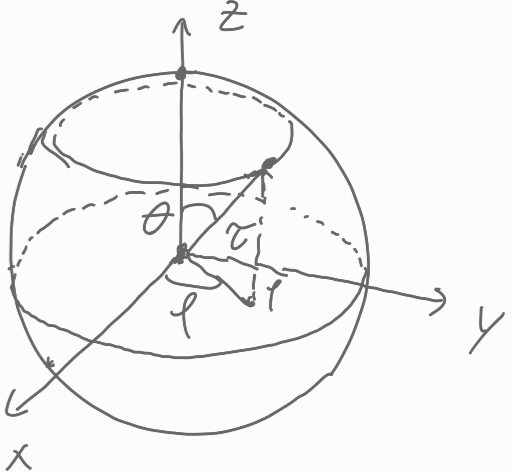

- Use geometric pictures again:

- The Bloch ball/sphere: all qubit states live inside a ball; the pure (maximally “sharp”) ones live on the surface.

- Explore advanced but intuitive ideas:

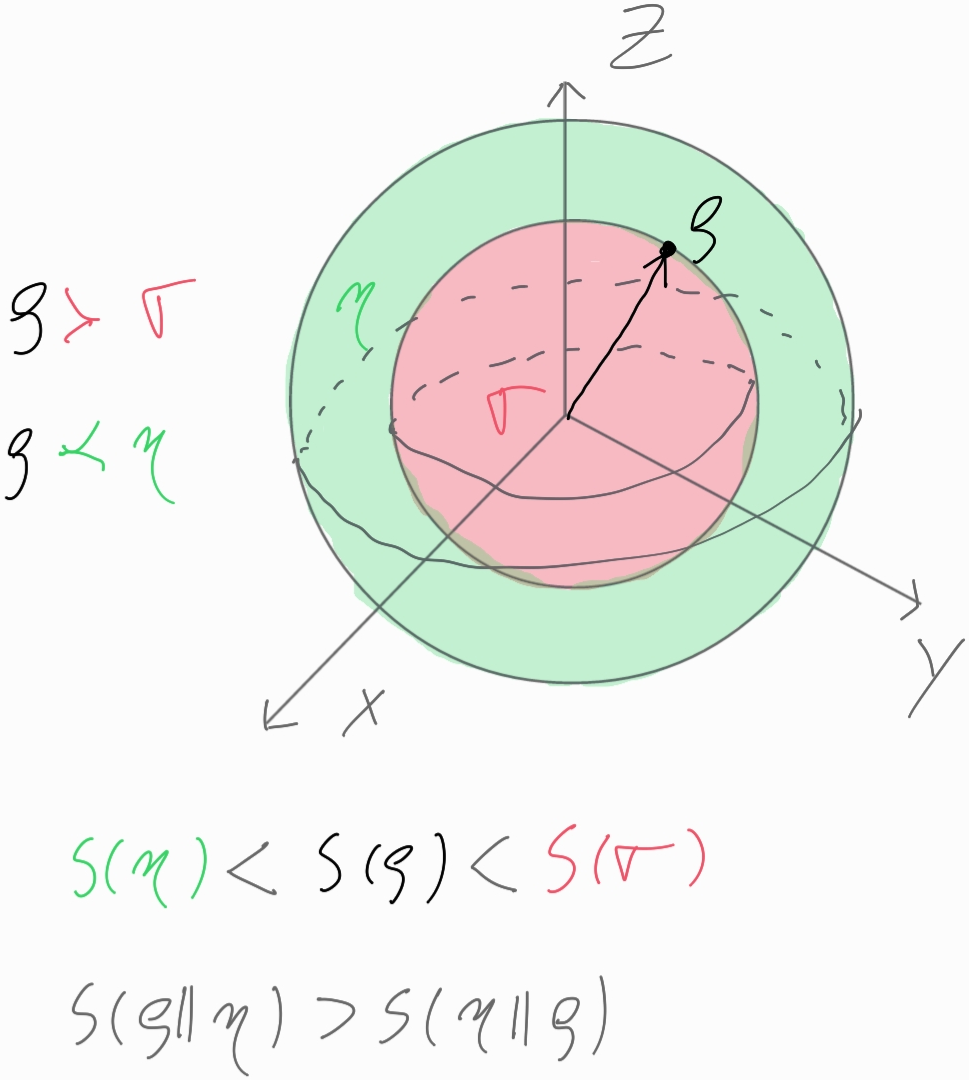

- Von Neumann entropy: the quantum version of Shannon entropy; it tells you the minimum possible uncertainty across all ways of measuring a quantum state.

- Quantum relative entropy: how easy it is to tell two quantum states apart with the best possible measurement.

- Fubini–Study (quantum) distance: the “largest possible” statistical distance you can get from comparing measurement outcomes of two pure quantum states.

- Entanglement and Schmidt decomposition:

- Entanglement: two systems can be linked so strongly that their parts look “mixed” even if the whole is perfectly pure.

- Schmidt decomposition: a neat way to write any two-part pure quantum state to understand its entanglement.

- Reduced density matrices: to predict outcomes for one part of a bigger system, you only need that part’s reduced density matrix.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

Here are the key ideas the paper explains and why they’re important:

- Four QML pairings make a roadmap:

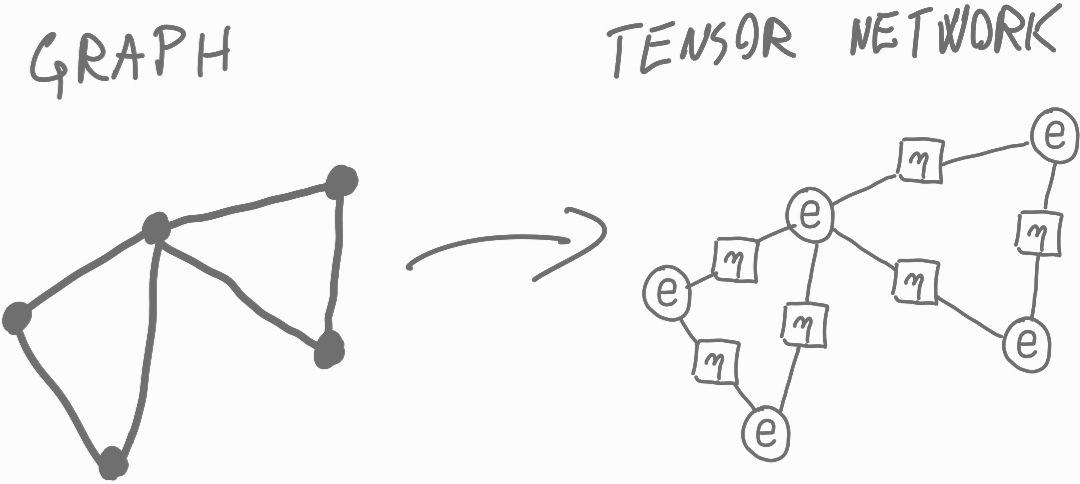

- CC: today’s machine learning; quantum-inspired tricks (like tensor networks) already help classical tasks.

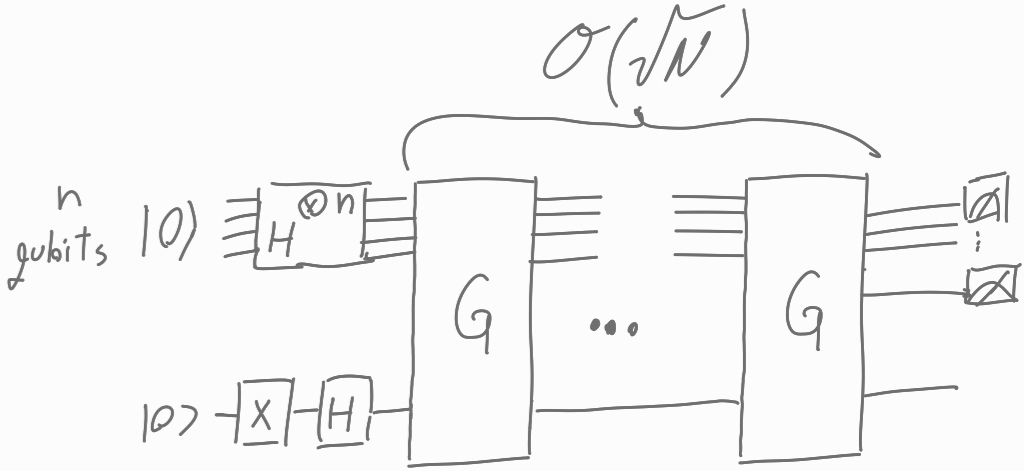

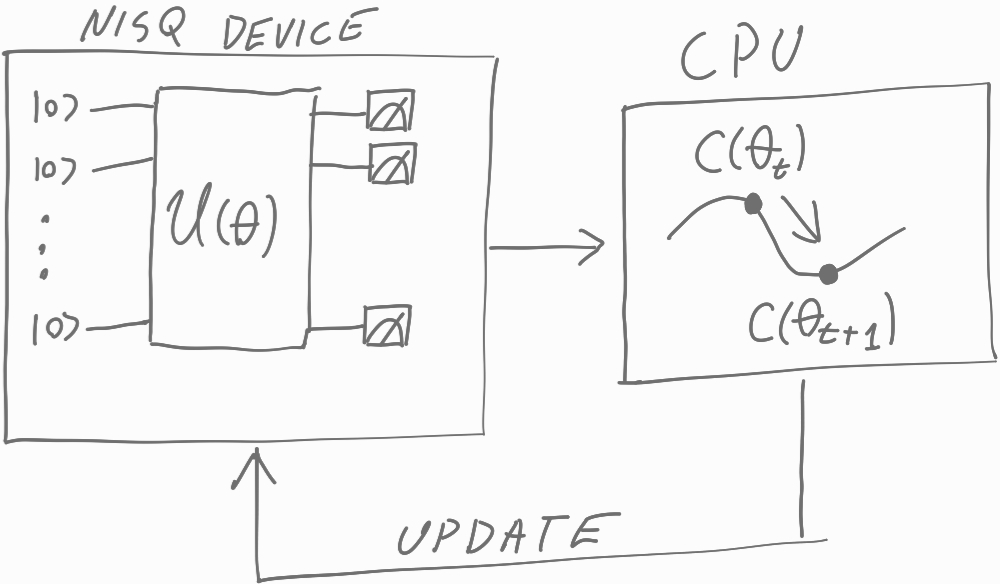

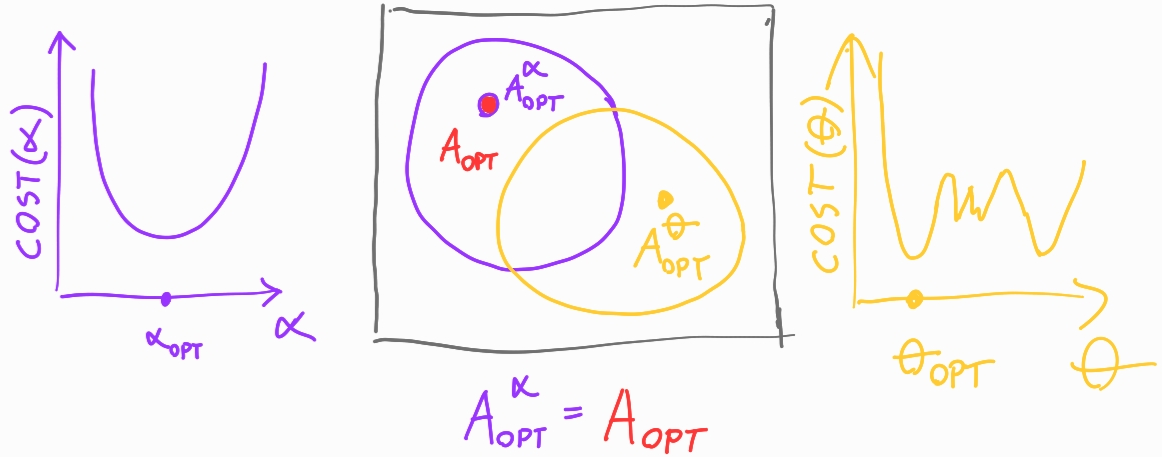

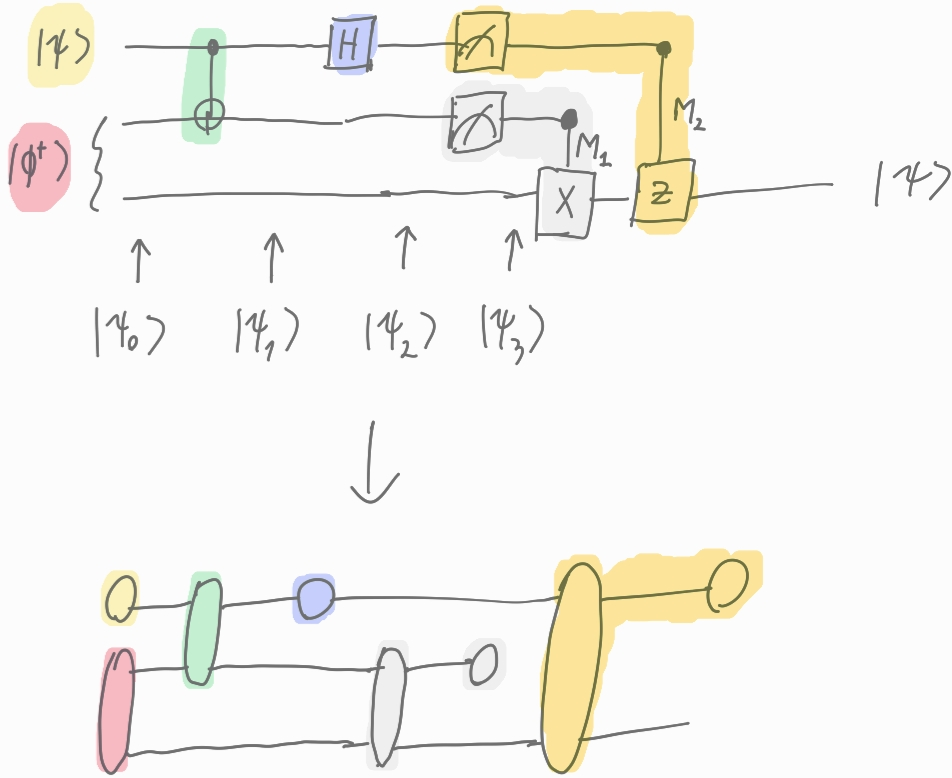

- CQ: the paper’s focus—use quantum circuits (like “variational quantum circuits,” which act like quantum neural networks) to speed up or improve parts of classical ML. This is promising for tasks that are hard to compute, to generalize, or to make robust.

- QC: use classical ML to analyze data from quantum experiments and calibrate devices.

- QQ: less explored now due to hardware limits; future uses include security (quantum cryptography).

- Classical vs. quantum probability:

- Classical probability is like mixing colors of paint: once mixed, you only have one color (no hidden phases).

- Quantum states are more like waves: besides “how much,” they have “phase” (how waves line up), which changes what you can see when you measure.

- This extra structure means a single quantum state can produce many different classical probability distributions depending on how you measure it.

- Pure vs. mixed states:

- Pure states are maximally sharp (they lie on the Bloch sphere’s surface).

- Mixed states are more “blended” (they lie inside the Bloch ball).

- Entropy measures how mixed you are; von Neumann entropy is the quantum version.

- Measurement and collapse:

- Just like updating beliefs after a coin flip, quantum states update after measurement.

- However, different choices of measurement can produce very different observed probabilities from the same quantum state.

- Entanglement:

- Entangled states can’t be split into independent parts; they’re truly quantum.

- The Schmidt decomposition explains and measures entanglement in a clean way.

- Any mixed state can be viewed as part of a larger pure state—this is called “purification.” It’s a powerful concept for modeling and algorithms.

- Distances and learning:

- Classical and quantum “distance” measures (like Fisher–Rao and Fubini–Study) help you compare distributions or states properly.

- In ML, using the “natural gradient” (inspired by Fisher–Rao) can speed up and stabilize training because it accounts for the curved geometry of probability space.

Implications and Potential Impact

- Better machine learning with quantum help (CQ): If quantum circuits can handle the hard parts of ML models (like certain feature transforms or optimization steps), we might train faster, generalize better, or be more robust to noise.

- Quantum-inspired tools for classical ML (CC): Even without quantum hardware, ideas born in quantum physics (like tensor networks) can simplify complex ML problems today.

- Smarter quantum experiments (QC): Classical ML can analyze results, discover patterns, and calibrate devices more reliably, helping quantum hardware perform better.

- Future secure systems (QQ): As quantum tech improves, fully quantum data and algorithms could power new applications like ultra-secure communication.

In short, understanding the differences between classical and quantum probability—and knowing how to measure uncertainty, distance, and entanglement—gives us the mathematical and geometric tools to build and evaluate quantum-enhanced machine learning. This foundation will help researchers decide where quantum computers can make a real difference and how to design algorithms that take advantage of uniquely quantum features.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single consolidated list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, stated concretely so future researchers can act on it.

- CQ scope and specificity: The paper commits to exploring CQ quantum machine learning but does not present any concrete algorithms, circuit architectures, or task formulations (e.g., classification, regression, kernel methods, generative models) that would allow empirical or theoretical assessment of advantage.

- Quantum-inspired classical algorithms: The mention of “dequantization of quantum recommender systems” is not accompanied by a systematic survey or a taxonomy of when dequantization is possible; specify the structural assumptions (e.g., sparsity, low rank, access models) under which each purported QML speedup collapses to a classical algorithm.

- Data encoding and state preparation: No discussion of practical classical-to-quantum data encodings (amplitude, angle, basis, qubit-efficient encodings), their asymptotic and constant-factor costs, and how those costs affect claimed runtime advantages and sample complexity.

- Measurement models: The exposition is restricted to projective measurements; extend all probability, entropy, and distance results to general POVMs and quantum instruments, and quantify how using POVMs changes optimal distinguishability and entropy bounds.

- Von Neumann entropy minimality: The statement that von Neumann entropy is the minimum of Shannon entropies over all projective measurements is asserted but not proved; provide a rigorous proof and generalize to POVMs (minimum over all measurements), including conditions for equality.

- Relative entropy for qubits: The given qubit relative entropy expression depends only on Bloch vector norms; derive the general formula for non-commuting qubit states (dependence on the angle between Bloch vectors), and characterize when asymmetry S(ρ‖σ) − S(σ‖ρ) is determined by purity versus orientation.

- Distances for mixed states: The link between the “quantum statistical distance” and the Fubini–Study angle is shown for pure states only; extend to mixed states via the Bures metric and quantum fidelity, and provide estimators from finite measurement samples with error bars.

- Majorization in quantum settings: The paper states that eigenvalue distributions majorize measurement outcome distributions; provide the formal proof, quantify the gap (e.g., via Schur-convex function differences), and explore how majorization can be used as a regularizer or capacity measure in QML models.

- Collapse/update dynamics: Only projective state update is treated; analyze weak measurements, noisy measurements, and post-selection, and quantify their effects on learning dynamics, gradients, and information retention.

- Reduced density matrices and reconstructability: The claim that quantum marginals “preserve just enough information to reconstruct the joint pure state” needs clarification; state precise uniqueness conditions (e.g., Schmidt coefficient degeneracies), characterize the family of global states compatible with given marginals, and give algorithms (with sample complexity) for reconstruction or certification.

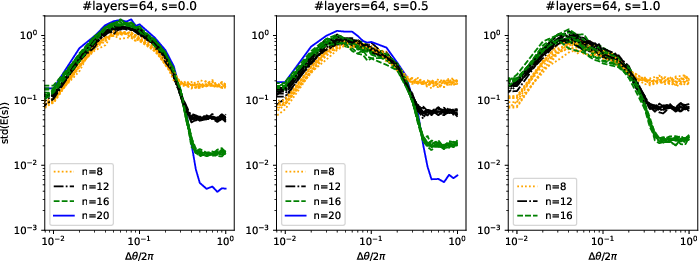

- Entanglement quantification: No entanglement measures (entropy of entanglement, concurrence, negativity) are introduced; investigate how entanglement levels impact expressivity, trainability (barren plateaus), and generalization in QML models.

- Quantum Fisher information and natural gradient: The classical Fisher–Rao metric is presented, but the quantum analogue (quantum Fisher information/Bures metric) and its use for natural-gradient training of variational circuits is missing; derive the metric, give efficient estimators on hardware, and evaluate training benefits versus shot cost.

- Complexity-theoretic claims: The paper suggests quantum help for “computation, generalisation or robustness” but provides no formal complexity or statistical learning theory guarantees; specify the oracle/data-access models (e.g., QRAM, block encodings), prove end-to-end runtime bounds (including state preparation and measurement), and provide generalization/sample complexity analyses.

- Shot noise and measurement overhead: There is no treatment of the number of measurements (shots) needed to estimate probabilities, entropies, or distances to a target precision; derive finite-sample bounds and their scaling with system size, depth, and noise.

- Noise and errors: Hardware noise, decoherence, and readout errors are not modeled; quantify how noise perturbs density-matrix geometry (entropy, fidelity), how it affects training (e.g., gradient variance), and evaluate error mitigation strategies in the context of the presented probabilistic framework.

- Kernel methods and feature maps: The paper does not connect the geometric notions (Fubini–Study, fidelity) to quantum kernel design; construct feature maps whose induced kernels reflect these metrics, analyze alignment and generalization bounds, and compare with dequantized or classical kernels.

- Barren plateaus and trainability: No discussion of gradient vanishing in variational circuits; characterize barren plateau conditions using the paper’s geometric tools (e.g., purity, majorization), and propose initialization or architecture constraints to avoid them.

- Benchmarking and datasets: Absent are standardized datasets, evaluation metrics, and experimental protocols to test CQ advantages; propose benchmark suites (including synthetic data with tunable structure), baselines, and reporting standards that incorporate encoding cost and shot complexity.

- Resource accounting: There is no qubit, gate-depth, or coherence-time accounting for the proposed learning tasks; develop resource models that map classical data size and model complexity to quantum hardware requirements and feasibility windows.

- Continuous-variable (CV) generalization: The framework is finite dimensional; extend probabilistic definitions, entropies, and distances to CV systems (Gaussian states, Wigner functions) relevant to photonic QML, and assess measurement and encoding costs.

- Identifiability from classical measurements: When only classical probabilities in a fixed basis are observed, analyze identifiability of underlying quantum states (ambiguity due to off-diagonal phases) and design measurement schemes to resolve ambiguities with minimal overhead.

- Efficient entropy estimation: Provide algorithms to estimate von Neumann entropy (or bounds via Rényi entropies/fidelity) from feasible measurements, with provable accuracy–sample trade-offs suited to NISQ devices.

- Practical CQ algorithms: Translate the probabilistic formalism into specific CQ pipelines (e.g., quantum-enhanced logistic regression, k-means via distance or fidelity, quantum PCA), detail training procedures (parameter-shift, natural gradient), and quantify end-to-end costs and accuracy relative to strong classical baselines.

- Assumption sensitivity and dequantization risk: For each proposed advantage, catalog the exact assumptions (data sparsity, low-rank structure, oracle access) and test robustness to violations, including the possibility of classical surrogates that match performance.

- Notational and rigor issues: Multiple typographical inconsistencies and informal derivations (e.g., measurement-update normalization, entropy signs, distance naming) need correction and formal proofs to prevent misinterpretation in downstream algorithm design.

Glossary

- Asymptotic equipartition property (AEP): A theorem stating that for IID sequences, the per-symbol log probability converges to the Shannon entropy. "First, we provide without a proof (which is simple) a fundamental theorem, namely the asymptotic equipartition property (AEP) theorem."

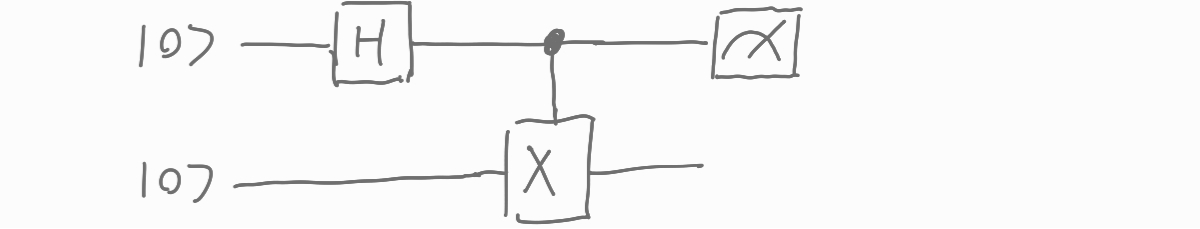

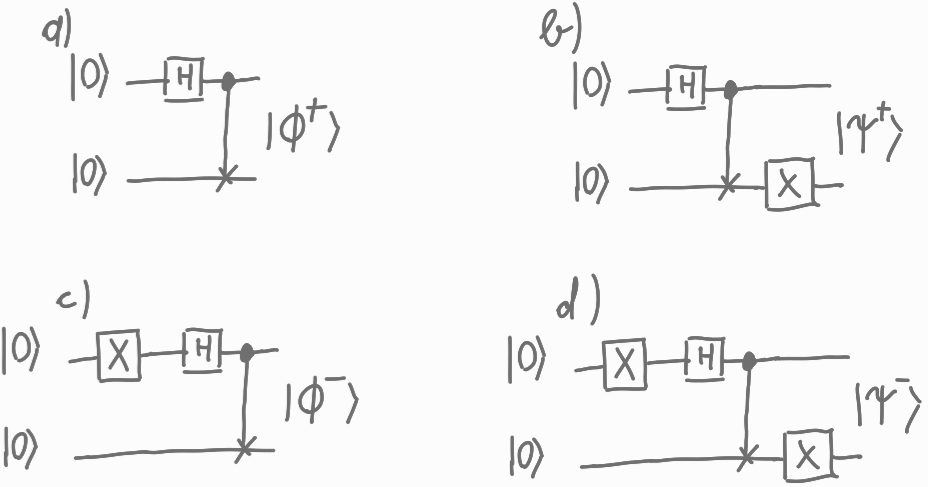

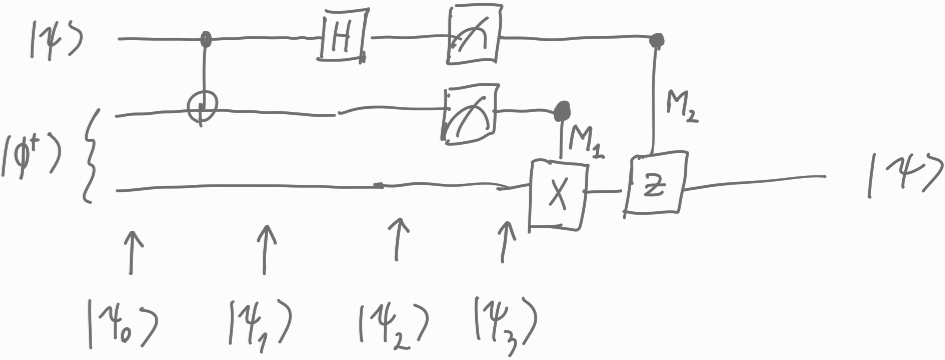

- Bell state: A maximally entangled two-qubit pure state, e.g., (|00⟩ + |11⟩)/√2. "A principal example of an entangled state is a Bell state"

- Battacharayya angle: A geometric measure of distance between classical probability distributions based on the inner product of square-root probabilities. "The geodesic distance between probabilities is the angle between the square roots of the probabilities (called the Battacharayya angle )"

- Bloch ball: The unit ball representing all qubit states; pure states lie on its surface. "As shown in the #1{fig: bloch sphere}, the probability manifold is a unit ball called the Bloch ball."

- Bloch sphere: The surface of the Bloch ball; it contains all pure qubit states. "Pure quantum states live on the surface of the unit ball (Bloch sphere)"

- Dequantization: The process of converting a quantum algorithm or model into an efficient classical counterpart. "A prominent example is the dequantization of quantum recommender systems."

- Density matrix: A matrix representation of a quantum state (pure or mixed) that is positive semidefinite and trace-one. "It is standard to call the quantum probability a density matrix."

- Entangled state: A composite quantum state that cannot be written as a tensor product of subsystem states. "We call such states entangled states."

- Fisher-Rao metric: An information-geometric metric that measures infinitesimal distances between probability distributions. "The metric determining the infinitesimal distance between probability distributions is the Fisher-Rao metric defined as"

- Hermiticity: A property of operators/matrices being equal to their conjugate transpose, ensuring real eigenvalues. "parametrise the most general density matrix satisfying the hermiticity and normalisation"

- Hilbert space: A complex vector space with an inner product in which quantum states (kets) live. "pure quantum probabilities are vectors in a complex Hilbert space"

- Majorisation: A partial order comparing the “uniformity” of vectors via cumulative sums of sorted components. "The simplest concept with which we can compare two probability distributions is majorisation."

- Natural gradient: An optimization direction that accounts for the curvature of the probability manifold via the Fisher-Rao metric. "the Fisher-Rao metric also defines the natural gradient."

- Pauli matrices: The set of 2×2 matrices σx, σy, σz used to represent qubit operators. "(Qubit) Let us revisit the qubit example #1{ex: qubit} and write the density matrix in terms of the ubiquitous Pauli matrices :"

- Partial trace: An operation that traces out a subsystem to obtain the reduced density matrix. "We calculate them by the partial trace operation as"

- Projective measurement: A measurement described by orthogonal projectors whose sum is identity. "As we have seen, a quantum probability determines many classical probabilities through projective measurements ."

- Qubit: The fundamental two-level quantum system, analogous to a classical bit. "Qubit Let us start with the simplest case (qubit)."

- Quantum relative entropy: A measure of distinguishability between quantum states defined as D(ρ||η) = Tr ρ (log ρ − log η). "Similarly as before, we define the quantum relative entropy by classical analogy"

- Quantum statistical distance (Fisher-Study distance): The geodesic distance between pure quantum states, equal to the maximal classical Bhattacharyya distance over measurements. "Quantum statistical distance (Fisher-Study distance)"

- Reduced density matrix: The density matrix of a subsystem obtained by tracing out the rest of the system. "In the fourth line, we introduced the reduced density matrix as a partial trace over the second system ."

- Sanov theorem: A large deviations result that gives the exponential rate at which empirical distributions deviate from the true distribution. "Sanov theorem (informal): Assume we are drawing samples from a probability distribution ."

- Schmidt decomposition: A representation of a bipartite pure state as a sum of orthonormal product states weighted by nonnegative coefficients. "An important tool to understand entangled states is the Schmidt decomposition"

- Superposition: The linear combination of basis states in a pure quantum state. "we only go this far with interpreting the superposition, which is operationally only a statement that a pure quantum state expressed in a chosen basis can have more than one non-zero component."

- Tensor networks: Structured factorizations of high-dimensional tensors used in quantum physics and machine learning. "utilising tensor networks for various machine learning tasks"

- Unitary transformation: A norm-preserving change of basis implemented by a unitary operator. "we can transform one set of projectors into another valid set of projectors by a unitary transformation ."

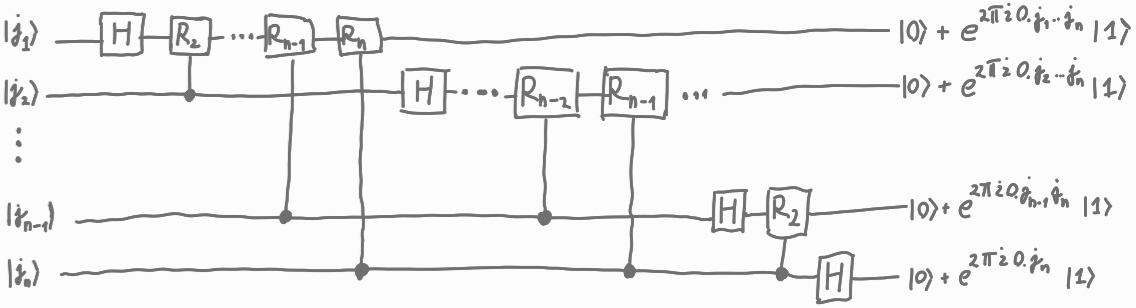

- Variational quantum circuit: A parameterized quantum circuit optimized (typically via classical methods) to minimize a loss function. "The most prominent quantum 'algorithm' is a variational quantum circuit, a quantum version of a neural network."

- von Neumann entropy: The quantum analogue of Shannon entropy defined as S(ρ) = Tr ρ log ρ. "It already represents the correct quantum analogue of the Shanon entropy, called von Neumann entropy."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a set of applications that can be put into practice now, drawing directly from the paper’s concepts (typology of QML, classical vs. quantum probability, entropy/distance measures, tensor networks, variational circuits, and calibration).

- Quantum-inspired classical machine learning with tensor networks (CC case)

- Description: Use tensor network models (e.g., matrix product states, tree tensor networks) for classification, anomaly detection, data embedding, language modeling, and generative modeling on classical hardware.

- Sectors: software, cybersecurity, manufacturing (quality control), finance (fraud detection), healthcare (diagnostics with structured data).

- Tools/products/workflows: ITensor/TeNPy/TensorNetwork libraries; PyTorch/TensorFlow layers with TT/MPS; TN-based anomaly detection pipelines; low-rank generative models for tabular/time-series.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data exhibits low-rank or locally correlated structure; engineers have expertise in TN training; careful regularization to prevent overfitting.

- Dequantized recommender systems (quantum-inspired classical algorithms)

- Description: Implement recommender algorithms derived from “dequantized” versions of quantum recommendation frameworks, delivering classical speed and scalability.

- Sectors: e-commerce, media streaming, advertising, finance (product recommendation).

- Tools/products/workflows: Spark/Databricks integrations; matrix factorization pipelines augmented with TN/SVD; evaluation via A/B testing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to scalable classical compute; sufficient sparsity/structure for dequantized methods to be competitive.

- Natural-gradient training via Fisher–Rao metric

- Description: Improve convergence and sample efficiency in probabilistic models by using the natural gradient (approximations to the Fisher information), directly motivated by the paper’s Fisher–Rao discussion.

- Sectors: healthcare (risk prediction), robotics (policy learning), finance (portfolio and risk models), education (adaptive testing).

- Tools/products/workflows: K-FAC and Fisher approximations in training loops; natural-gradient schedules; model-debugging dashboards tracking curvature/entropy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate/stable Fisher approximations; model architectures compatible with K-FAC; computational overhead justified by convergence gains.

- ML-assisted calibration of quantum devices (Q data + C algorithms)

- Description: Use classical ML (Bayesian optimization, reinforcement learning) to automate calibration of qubits and experimental parameters; directly referenced as a key QML use case in the typology.

- Sectors: quantum hardware providers, telecom (quantum communication pilots).

- Tools/products/workflows: Calibration-as-a-Service; Bayesian/RL tuning agents integrated with control electronics; drift monitoring and re-calibration triggers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to device APIs, stable measurement interfaces; consistent noise models; safe RL exploration policies.

- Measurement design and state discrimination using von Neumann and quantum relative entropy

- Description: Choose measurement bases that minimize uncertainty (von Neumann entropy) and maximize distinguishability (quantum relative entropy) to improve sensing and hypothesis testing.

- Sectors: quantum sensing and metrology, materials science (quantum experiments), defense.

- Tools/products/workflows: Optimization routines selecting projectors/unitaries; experiment planners maximizing information gain; entropy/relative-entropy dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ability to implement tailored projective measurements; manageable decoherence; accurate modeling of noise and state-preparation errors.

- Hybrid quantum-classical workflow design using the collapse/update rule

- Description: Embed the measurement update rule ρ → ΠρΠ / Tr(ΠρΠ) into variational quantum circuit (VQC) training and mid-circuit measurement workflows.

- Sectors: software (quantum SDKs), quantum algorithm prototyping.

- Tools/products/workflows: Qiskit/PennyLane workflows with explicit post-measurement state handling; measurement-aware optimization loops.

- Assumptions/dependencies: NISQ device access; reliable mid-circuit measurement; small circuits due to decoherence.

- Statistical distance monitoring with the Bhattacharyya angle

- Description: Monitor dataset shift or distribution drift using the Bhattacharyya angle (a consequence of the Fisher–Rao geometry), and corresponding classical distance analogs.

- Sectors: ML Ops, finance (market regime detection), cybersecurity (distribution shift in logs).

- Tools/products/workflows: Drift monitors; alerting when geodesic distance exceeds thresholds; retraining triggers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Well-estimated distributions; sufficient sample sizes; robust thresholds calibrated to domain risk.

- Small-scale variational quantum circuits (CQ case)

- Description: Deploy VQCs for toy feature maps/kernels and small classification tasks on cloud-accessible NISQ devices.

- Sectors: software (R&D), education (hands-on quantum labs).

- Tools/products/workflows: Qiskit/PennyLane circuits; hybrid optimizers (e.g., SPSA) with entropy-based regularizers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Limited qubit count and coherence; careful encoding (data-loading overhead may dominate); realistic expectations (proof-of-concept, not advantage).

- Education and workforce development using the paper’s QML typology and unified formalism

- Description: Incorporate CC/CQ/QC/QQ typology and the probability/density-matrix “dictionary” into curricula and internal training for clearer mental models.

- Sectors: higher education, enterprise training, public-sector upskilling.

- Tools/products/workflows: Course modules, lab notebooks; “probability-to-density” cheat-sheets; interactive visualization of Bloch sphere/majorization/entropy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Trained instructors; alignment with degree requirements; access to simulators.

- Quantum key distribution (QQ case) in production networks

- Description: Deploy QKD as a mature example of quantum-data/quantum-algorithm systems, noted in the paper as a plausible QQ application.

- Sectors: finance, government, critical infrastructure.

- Tools/products/workflows: Commercial QKD systems; link budget planning; key management integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Fiber/free-space infrastructure; compliance and procurement; integration with classical crypto systems.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, hardware development, or ecosystem standardization before broad deployment.

- Quantum advantage for classical ML (CQ case)

- Description: Replace computational bottlenecks (e.g., kernel evaluation, linear-algebra subroutines, optimization) with quantum subroutines to improve computation/generalization/robustness.

- Sectors: healthcare (drug discovery, genomics), energy (grid optimization), finance (risk, pricing), logistics (routing).

- Tools/products/workflows: Hybrid solvers that offload linear-algebra or kernel estimation; entropy/majorization-guided model selection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Fault-tolerant quantum computers; scalable error correction; efficient data loading/QRAM; rigorous advantage proofs beyond toy problems.

- Quantum-native ML on quantum data (QQ case)

- Description: Learning tasks on quantum measurement records (state classification, tomography, control), leveraging entanglement, Schmidt structure, and optimal measurements.

- Sectors: quantum hardware R&D, materials characterization, quantum chemistry.

- Tools/products/workflows: Adaptive measurement strategies; learning-based tomography; control policies trained on reduced density matrices.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Longer coherence times; mid-circuit control; robust interfaces between classical learners and quantum experiments.

- Entanglement-aware model design for complex classical data

- Description: Use Schmidt decomposition and tensor networks to architect models that capture correlation structure akin to entanglement (graphs, sequences, multimodal).

- Sectors: social networks (graph analytics), bioinformatics (protein/genomic interactions), NLP (long-context modeling).

- Tools/products/workflows: “Entanglement-regularized” architectures; scalable TN training (MPS/PEPS/tree TN); interpretable correlation diagnostics via majorization metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Advances in TN scaling and GPU/TPU kernels; robust training heuristics; domain-specific feature engineering.

- Measurement-optimized quantum sensing (entropy/relative-entropy design)

- Description: Engineer sensors and experiments where measurement bases are chosen to minimize von Neumann entropy or maximize quantum relative entropy for target hypotheses.

- Sectors: metrology, defense, geological exploration, medical imaging (quantum probes).

- Tools/products/workflows: Real-time basis optimization; Fisher–Study distance as a design criterion; closed-loop sensing with ML controllers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reconfigurable measurement hardware; fast optimization loops; reliable physical models of signal and noise.

- Standards and policy for QML benchmarking and reporting

- Description: Use entropy, majorization, and quantum statistical distances as standardized metrics for QML benchmarking and transparency.

- Sectors: policy/regulation, funding agencies, industry consortia.

- Tools/products/workflows: Benchmark suites reporting von Neumann entropy, quantum relative entropy, and statistical distances; typology-based capability maps (CC/CQ/QC/QQ).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community consensus and governance; reproducibility frameworks; open datasets and protocols.

- Quantum-enhanced cryptography with ML for channel estimation and attack detection

- Description: Integrate ML into QKD-like systems for adaptive error correction, channel characterization, and anomaly detection.

- Sectors: telecom, defense, finance.

- Tools/products/workflows: ML sidecar services monitoring entropy and relative entropy trends; adaptive coding/decoding strategies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Mature integration of classical ML with quantum communication stacks; regulatory approvals.

- AutoML for hybrid quantum-classical pipelines

- Description: Automated selection of encodings, variational ansätze, measurement bases, and optimizers guided by entropy/majorization criteria.

- Sectors: software (ML platforms), quantum cloud services.

- Tools/products/workflows: Pipeline orchestration across SDKs (Qiskit, PennyLane); measurement-aware hyperparameter tuning; collapse-rule-aware training loops.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable hardware APIs; standardized intermediate representations; datasets suited to hybrid processing.

- Quantum-assisted optimization in energy and robotics

- Description: Use variational or future fault-tolerant quantum methods for complex control/optimization problems (grid balancing, motion planning).

- Sectors: energy, robotics, autonomous systems.

- Tools/products/workflows: Hybrid solvers with entropy-based stopping criteria; robustness diagnostics via statistical distances.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware scaling; robust mappings from domain problems to suitable quantum formulations; safety verification.

- Finance: quantum Monte Carlo and state discrimination

- Description: Accelerate sampling and model validation with quantum subroutines; use entropy/distance metrics for regime-change detection or model comparison.

- Sectors: finance (pricing, risk).

- Tools/products/workflows: Hybrid sampling engines; “entropy radar” for market monitoring; relative-entropy model audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Fault-tolerant devices; provable speedups; compliance with model risk management standards.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.