High-Performance DBMSs with io_uring: When and How to use it (2512.04859v1)

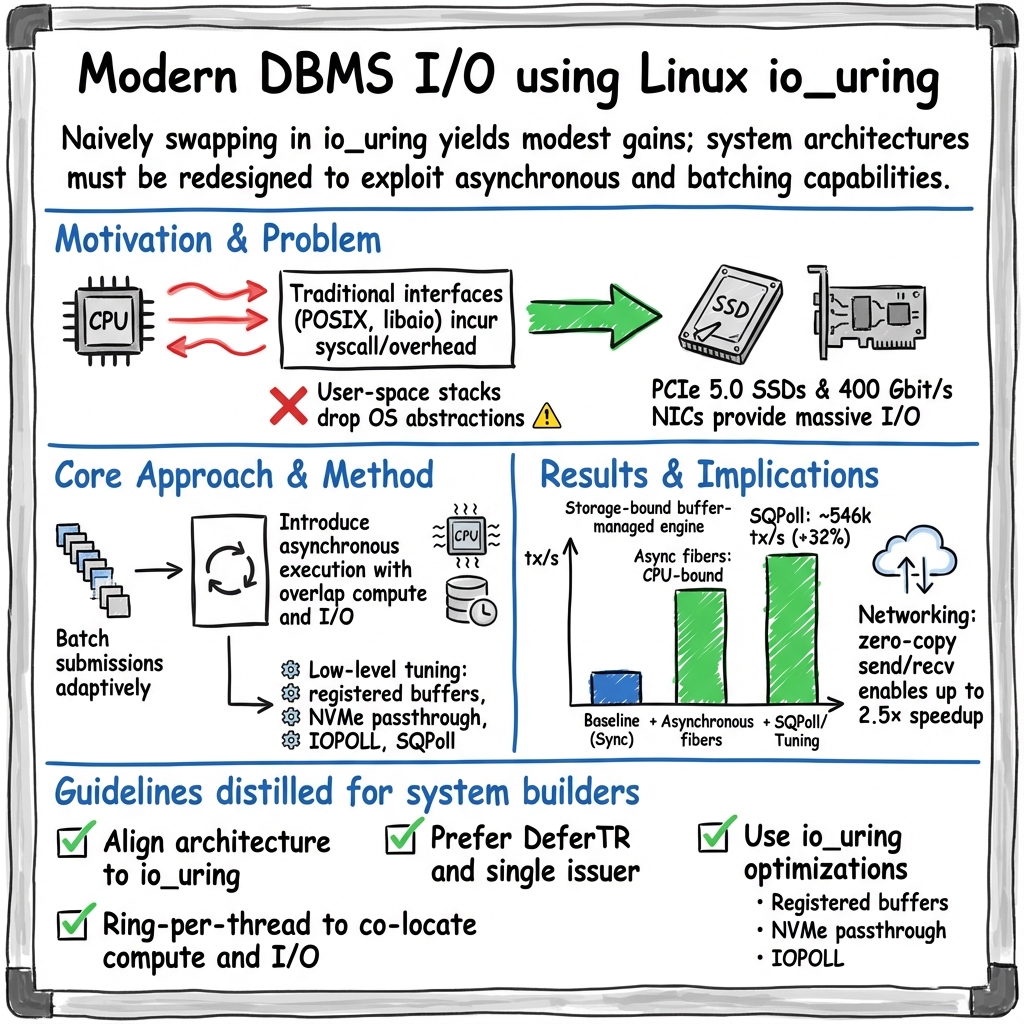

Abstract: We study how modern database systems can leverage the Linux io_uring interface for efficient, low-overhead I/O. io_uring is an asynchronous system call batching interface that unifies storage and network operations, addressing limitations of existing Linux I/O interfaces. However, naively replacing traditional I/O interfaces with io_uring does not necessarily yield performance benefits. To demonstrate when io_uring delivers the greatest benefits and how to use it effectively in modern database systems, we evaluate it in two use cases: Integrating io_uring into a storage-bound buffer manager and using it for high-throughput data shuffling in network-bound analytical workloads. We further analyze how advanced io_uring features, such as registered buffers and passthrough I/O, affect end-to-end performance. Our study shows when low-level optimizations translate into tangible system-wide gains and how architectural choices influence these benefits. Building on these insights, we derive practical guidelines for designing I/O-intensive systems using io_uring and validate their effectiveness in a case study of PostgreSQL's recent io_uring integration, where applying our guidelines yields a performance improvement of 14%.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about (in simple terms)

This paper asks a practical question: How can modern databases talk to super-fast disks and networks without wasting time? It studies a new Linux tool called io_uring that promises faster input/output (I/O) and shows when it really helps, how to use it, and which tricks make it shine.

Think of a database like a busy library. It constantly needs to fetch and return “books” (data) to shelves (disks) and send/receive packages (network). If the librarians (the CPU) spend lots of time waiting in line to check things in and out (old I/O methods), the library gets slow. io_uring is like giving them rolling carts, a shared inbox/outbox, and the ability to send batches all at once, so they stop wasting time.

The main goals and questions

The paper focuses on three simple questions:

- When should databases use io_uring? In what kinds of jobs does it help the most?

- How should databases be redesigned to make io_uring actually pay off?

- Which io_uring features (like batching, buffer registration, polling) matter most for speed?

How the researchers tested their ideas

They used two real database jobs and several small, focused tests:

- Storage-heavy case: A “buffer manager” that loads and evicts data pages to/from super-fast NVMe SSDs. This is like the library’s main book cart system.

- Network-heavy case: A “data shuffle” for distributed analytics over 400 Gbit/s networks, where many servers swap data for big joins. This is like many libraries swapping books at high speed.

They compared “naive” use of io_uring (just swapping old I/O calls for new ones) against smarter designs that use io_uring’s special powers: doing things asynchronously (don’t block while waiting), batching many operations at once, and using advanced features like registered buffers and passthrough I/O.

They also measured:

- How many CPU cycles each step costs (like timing how long each librarian task takes).

- How latency changes when batching more or less.

- How well things scale from one CPU core to many.

- How different workloads (I/O-bound vs. mostly in-memory) change the results.

To make async work smoothly in the storage engine, they ran each transaction as a lightweight coroutine (“fiber”). A fiber is like a tiny co-operative worker: if it needs to wait for I/O, it politely yields, and another fiber runs. This keeps the CPU busy instead of sitting idle.

What they found (and why it matters)

1) Just switching to io_uring isn’t enough

If you simply replace old I/O calls with io_uring calls but keep the same design, you get only tiny gains (about 1.06× for storage, 1.10× for networking). It’s like getting a faster conveyor belt but still handing items one-by-one—most time is still wasted.

2) Redesigning around async + batching makes a big difference

When they redesigned to really use io_uring’s strengths:

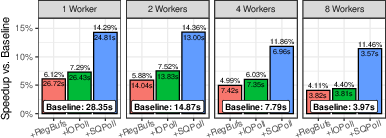

- In the storage case (single core), throughput jumped from about 16.5k transactions per second to about 546k—over 30×—by progressively:

- Batching evicted-page writes so one system call submits many I/Os at once.

- Making reads and writes asynchronous so the CPU does useful work while I/O is in flight (using fibers).

- Batching read submissions to cut system call overhead.

- Turning on advanced features (see below).

Key idea: Don’t wait for I/O. Overlap it with useful work and send I/O in batches.

3) Advanced io_uring features give extra boosts (especially when I/O dominates)

Once the design is async and batched, turning on low-level features helps a lot:

- Registered buffers: Pre-approve memory so the kernel can do zero-copy DMA straight into your space. About +11% in their storage test.

- NVMe passthrough: Skip general OS layers and speak more directly to the SSD. About +20%.

- I/O polling (IOPoll): Poll instead of being interrupted for completions. About +21%. Great when there’s lots of I/O; can waste CPU if there isn’t.

- Submission-queue polling (SQPoll): A kernel thread watches your submissions so you avoid system calls to submit. About +32%. Costs a core, so it pays off mainly when I/O is heavy.

Together, these pushed the one-core storage test to ~546k TPS.

4) Workload matters: I/O-bound wins big; in-memory gains are smaller

- For an update-heavy YCSB-like workload (lots of page faults): big benefits.

- For TPC-C:

- With most data in memory (compute-bound), I/O tricks help less. Polling may even hurt because it spins when there’s not much I/O.

- With data larger than memory (out-of-memory, I/O-bound), the gains are strong again.

Translation: io_uring helps most when you frequently hit disk or move lots of data over the network.

5) Batching has a trade-off: throughput vs. latency spikes

Bigger batches reduce CPU overhead and can increase device throughput. But they can also cause latency spikes (some requests wait longer). For latency-sensitive workloads, use moderate batch sizes and adaptive flushing (send what you have when few operations are pending).

6) Bigger I/O sizes help, but don’t exceed hardware/software limits

Larger I/O blocks lower CPU cost per byte and can saturate PCIe 5 SSDs. However, going too big can trigger slower fallback paths (worker threads) due to device or kernel limits. Know your thresholds (like max sectors per request).

7) Durable writes are tricky

Making sure data is truly safe on disk (fsync) is expensive and often blocking. Options:

- fsync: simple but blocks (slower).

- O_SYNC: often slower than “write + fsync.”

- NVMe flush via passthrough: fastest async option, but usually needs raw device access (no filesystem). On enterprise SSDs with power-loss protection, durable writes can be much faster than on consumer SSDs.

8) Networks benefit too when designed right

For data shuffling over 400 Gbit/s networks, a careful io_uring design got about 2.31× over a naive approach. Unifying storage and network I/O through one async interface reduces complexity and overhead.

9) Real system validation: PostgreSQL

They applied their guidelines to PostgreSQL’s io_uring backend and got a 14% performance improvement—evidence the ideas carry over to real systems.

What this means going forward

- When to use it: io_uring shines in I/O-intensive situations—lots of page faults, big shuffles, high-throughput SSDs and NICs. If most work is in CPU and memory, the gains are smaller.

- How to use it: Don’t just swap APIs—redesign around asynchronous execution and batching. Use coroutines/fibers to keep the CPU busy while I/O is in flight.

- How to tune it: Turn on advanced features (registered buffers, passthrough, polling) when I/O is heavy. Pick batch sizes carefully to avoid latency spikes. Watch for limits that trigger slow fallback paths. Be thoughtful with durability (fsync vs. NVMe flush) and the kind of SSD you use.

In short, io_uring can turn today’s super-fast disks and networks into real-world performance gains, but only if databases are architected to take advantage of it. Done right, it reduces wasted CPU time, overlaps work with I/O, and delivers large speedups in the jobs where it matters most.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, phrased to enable concrete follow-up research and engineering work.

- Mixed I/O modality orchestration

- How to architect DBMS event loops when storage uses IOPOLL/SQPOLL (which constrain sockets) but networking needs interrupt-driven completions, including ring partitioning, cross-ring backpressure, and fairness when storage and network I/O are concurrent in the same operator or transaction path.

- Auto-tuning of batching and polling

- Formalize and evaluate adaptive policies that switch SQPOLL/IOPOLL on/off and tune batch sizes and submission intervals based on load, tail-latency targets, and device queue occupancy, including stability and convergence under rapid workload shifts.

- Tail-latency SLAs under batching

- Develop SLO-aware batching strategies that bound p99/p999 transaction and I/O latency while retaining throughput gains, and quantify the latency/throughput Pareto front across SSD/NIC queues and application-level queues.

- Broader workload coverage

- Evaluate beyond uniform-update YCSB and TPC-C: skewed access (e.g., Zipf), mixed read/write ratios, long-running analytical queries, background tasks (checkpointing, compaction, vacuum), and mixed OLTP/OLAP to stress interaction effects with batching and polling.

- End-to-end DBMS integration

- Assess io_uring impact on full systems (e.g., MVCC, group commit, WAL, checkpoint, recovery, replication, vacuum), including contention in lock manager/latches when asynchronous fibers resume and re-traverse shared data structures.

- Durability semantics and correctness

- Precisely characterize ordering and durability guarantees across fsync, O_SYNC, NVMe FUA/flush via passthrough, and linked SQEs, especially under crashes; provide validated recipes for WAL correctness with and without filesystems.

- Filesystem diversity and configuration

- Systematically evaluate ext4/xfs/btrfs (modes: data=ordered/journaled, DAX), buffered vs O_DIRECT, and mount options on io_uring performance, worker fallbacks, and durability; produce FS-specific guidance or autotuning.

- Device and platform heterogeneity

- Generalize results across broader SSD/NIC sets (consumer vs enterprise, PLP/no-PLP), NVMe queue depths, IOMMU on/off, SR-IOV/VF devices, virtualization (KVM, cloud NVMe/NICs), and ARM vs x86 servers.

- NUMA and topology-aware scheduling

- Devise policies for pinning submission threads, SQPOLL, io_wq workers, and NVMe/NIC queues to sockets/chiplets; measure cross-NUMA penalties, ring-per-NUMA designs, and queue-to-core affinity for passthrough.

- io_wq fallback characterization and avoidance

- Map the precise thresholds (block size, nr_requests, max_segments, max_hw_sectors_kb, FS behaviors) that trigger io_wq; build detection/telemetry and avoidance strategies (coalescing, segmentation, per-ring caps) that maintain asynchronous paths.

- Energy and resource efficiency

- Quantify power and CPU-efficiency trade-offs of busy polling (SQPOLL/IOPOLL) under low and bursty load; explore hybrid polling/interrupt schemes and core budgeting policies for shared machines.

- Networking specifics left unexplored

- Analyze io_uring with high-speed TCP features: GSO/TSO, MSG_ZEROCOPY, multishot recv, SO_BUSY_POLL, RSS/queue steering, congestion control interactions at 200–400 Gbit/s, TLS offload, and kernel bypass comparisons.

- Storage vs userspace stacks comparison

- Provide head-to-head comparisons and decision guidelines versus SPDK (storage) and DPDK/RDMA (network) under shared-device constraints, multi-tenant environments, and production feature requirements (filesystems, TCP).

- Observability and operability

- Define and implement metrics to detect pathological states: ring saturation, CQ overflow, unintended preemptions, IPI storms, io_wq usage spikes, and queue-depth oscillations; integrate with eBPF tracing for production debugging.

- Robustness under failures and overload

- Evaluate cancellation, timeouts (e.g., OP_LINK_TIMEOUT), error propagation, and recovery semantics under device errors, packet loss, or kernel backpressure; propose backoff and shedding strategies compatible with io_uring.

- Cross-operator and pipeline interactions

- Study how asynchronous I/O scheduling in one operator (e.g., shuffle) impacts upstream/downstream operators (e.g., join, aggregation) regarding buffer occupancy, memory pressure, and overall pipeline throughput/latency.

- Memory management with registered buffers

- Investigate fragmentation, NUMA placement, lifetime management, cgroup limits, and security/isolation risks of long-lived pinned memory; propose allocator and registration schemes that balance zero-copy gains with flexibility.

- Formal performance modeling

- Extend the simple latency/cycle models to predictive, device-aware models incorporating queueing (device and software), batching, polling, and CPU contention, enabling a priori configuration selection and online adaptation.

- Multi-tenant fairness and isolation

- Examine how multiple rings/processes compete for SSD/NIC queues (with and without passthrough) and how cgroups/io.cost/io.max interact with io_uring; propose fairness mechanisms that maintain isolation under aggressive batching/polling.

- Portability and kernel-version sensitivity

- Document how results vary with kernel versions, liburing features (e.g., SQE128/CQE32), and distro defaults (I/O scheduler, IRQ affinity); provide compatibility fallbacks and migration guidance.

- Security and compliance aspects

- Analyze security implications of passthrough and direct device access in shared environments, including namespace/partition boundaries, TRIM handling, and auditability when bypassing filesystem layers.

- Comprehensive network-storage co-saturation

- Demonstrate end-to-end scenarios that simultaneously saturate 400 Gbit/s links and high-IOPS SSD arrays, detailing CPU/core budgets, queue mappings, and interference management, or identify where fundamental bottlenecks arise.

- Impact on SSD endurance and write amplification

- Quantify how write batching and larger I/O sizes influence device-internal GC, WA, and lifetime, and derive safe operating regions or firmware-aware tuning.

Glossary

- B-tree: A balanced tree data structure commonly used for indexing in databases, enabling efficient insertions, deletions, and lookups. "The storage engine includes a B-tree index for tuple access and updates."

- Boost.fibers: A C++ user-space cooperative multitasking library providing fibers (lightweight threads) and schedulers. "We extend the buffer manager with Boost.fibers~\cite{boostfiber} for cooperative scheduling,"

- clock-sweep: A buffer replacement algorithm used in DBMSs that approximates LRU by marking pages in passes and evicting unreferenced ones. "In this paper, we use clock-sweep \cite{PostgresClockSweep},"

- COOP_TASKRUN: An io_uring flag that reduces inter-processor interrupts by deferring kernel task_work when possible. " offers the \ttsafe{COOP_TASKRUN} flag (CoopTR), which reduces IPIs and allows applications to delay task_work."

- Completion Queue (CQ): The shared ring buffer in io_uring where the kernel posts results of completed operations. "the Completion Queue (CQ) for receiving results."

- completion-based model: An I/O event model where the application is notified on operation completion rather than readiness. "In contrast to epoll's readiness-based polling approach, employs a completion-based model, notifying applications after operations complete rather than when they become possible."

- DEFER_TASKRUN: An io_uring flag that runs kernel task_work only on explicit io_uring_enter calls to avoid unwanted preemptions. "The \ttsafe{DEFER_TASKRUN} flag (DeferTR) only runs task_work on io_uring_enter calls,"

- DMA: Direct Memory Access, allowing devices to read/write memory without CPU involvement, reducing copy overhead. "The kernel then performs DMA directly into user memory,"

- DPDK: A user-space packet processing framework that bypasses the kernel for high-performance networking. "User-space I/O frameworks such as DPDK, SPDK, and RDMA bypass the kernel and can deliver high performance on dedicated hardware"

- epoll: A Linux interface for scalable I/O readiness notification on multiple file descriptors (mostly sockets). "or instead of epoll for a network shuffle,"

- fsync: A system call that forces buffered file data to be committed to stable storage for durability. "such as \ttsafe{fsync}, or large storage reads."

- IOPOLL: An io_uring mode where completions are polled from device queues instead of using interrupts, reducing overhead. "With IOPOLL, completion events are polled directly from the NVMe device queue,"

- IOPS: Input/Output Operations Per Second, a throughput metric for storage devices. "(2.45M IOPS)"

- IPI: Inter-Processor Interrupt, used by the kernel to interrupt another CPU core, e.g., to process pending completions. "the kernel may issue an inter-processor interrupt (IPI) to process pending completions."

- io_uring_enter: The syscall used by applications to submit and/or wait for batched io_uring operations. "with a single io_uring_enter syscall."

- io_worker: Kernel worker threads used by io_uring to execute operations that cannot proceed asynchronously. "delegates execution to worker threads (\ttsafe{io_worker})."

- IOSQE_ASYNC: An io_uring submission flag that forces a request to run in a worker thread (asynchronous path). "Applications can explicitly request this behavior using the IOSQE_ASYNC flag,"

- libaio: The older Linux asynchronous I/O interface primarily targeting direct block I/O, often lacking fully async semantics. "instead of libaio for storage I/O"

- madvise: A system call allowing applications to give the kernel advice about memory usage patterns. "beyond I/O-related system calls (e.g., madvise),"

- NVMe: Non-Volatile Memory Express, a high-performance storage protocol for SSDs over PCIe. "NVMe SSDs such as the Kioxia CM7-R"

- NVMe passthrough: Bypassing the generic storage stack by issuing native NVMe commands directly via io_uring to device queues. "NVMe passthrough skips abstractions."

- O_DIRECT: A file open flag that performs direct I/O, avoiding the page cache for block device access. "direct block-device access via \ttsafe{O_DIRECT}."

- O_SYNC: A file open flag that makes writes synchronous, ensuring data reaches stable storage for durability. "opening files with \ttsafe{O_SYNC},"

- OP_LINK_TIMEOUT: An io_uring opcode used to set a timeout for linked operations. "By default, waits indefinitely for the operation unless a timeout via \ttsafe{OP_LINK_TIMEOUT} is set."

- OP_URING_CMD: An io_uring opcode for issuing custom commands, e.g., native NVMe commands to device queues. " provides the \ttsafe{OP_URING_CMD} opcode,"

- PCIe 5.0: A high-speed peripheral interconnect standard used by modern SSDs and NICs, offering very high bandwidth. "Modern PCIe 5.0 hardware,"

- Power Loss Protection (PLP): Hardware features in enterprise SSDs to protect in-flight data during power failures. "Power Loss Protection (PLP)"

- RDMA: Remote Direct Memory Access, enabling direct memory reads/writes between hosts over the network with low latency. "DPDK, SPDK, and RDMA"

- registered buffers: Memory regions pre-registered with io_uring to avoid per-I/O pinning and copies, enabling zero-copy DMA. "registered buffers and passthrough I/O,"

- Submission Queue (SQ): The shared ring buffer in io_uring where applications enqueue I/O requests for the kernel. "the Submission Queue (SQ) for enqueuing I/O requests"

- SQPoll: An io_uring mode with a dedicated kernel thread polling the submission queue to eliminate submission syscalls. "when applications set up with the SQPoll mode,"

- task_work: Kernel work items executed in the context of a task to finalize operations, e.g., placing completions into the CQ. " must run task_work in the kernel"

- TPC-C: A standard OLTP benchmark modeling complex transaction mixes for evaluating database performance. "the more complex, compute-bound TPC-C workload."

- write-ahead logging: A durability technique where changes are first recorded in a log before being applied, ensuring recoverability. "Durable writes are essential for database systems, particularly for write-ahead logging and checkpointing,"

- YCSB: Yahoo! Cloud Serving Benchmark, a standard benchmark for evaluating key-value store and DBMS performance. "single-statement, I/O-intensive YCSB-like transactions"

- zero-copy: An optimization that avoids copying data between kernel and user space by using DMA directly into user buffers. "This zero-copy optimization improves throughput"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following items summarize applications that can be deployed today by leveraging the paper’s findings on how and when to use io_uring effectively in high-performance database systems. Each bullet includes sector links and feasibility notes.

- High-throughput OLTP databases: retrofit buffer managers to use cooperative-asynchronous execution

- What: Replace blocking I/O with fibers/coroutines that submit reads/writes via

io_uring, yield on page faults, and resume on completion; batch eviction writes and batch read submissions; useDEFER_TASKRUNto avoid kernel preemption overhead. - Where: Software (DBMS vendors and open-source projects, e.g., PostgreSQL, MySQL forks, commercial OLTP engines).

- Why: Shifts bottleneck from device latency to CPU cycles, enabling sustained throughput increases (e.g., 10–12× in I/O-bound cases; 14% measured improvement in PostgreSQL’s

io_uringbackend). - How/tools: Integrate a fiber runtime (e.g., Boost.Fibers), adopt ring-per-thread, adaptive batching, and request linking; instrument with cycle counters (

rdtsc) to validate model predictions. - Assumptions/dependencies: Linux kernel with modern

io_uringfeatures; liburing available; developers able to modify buffer manager logic; workloads with non-trivial page-fault rates.

- What: Replace blocking I/O with fibers/coroutines that submit reads/writes via

- Managed Postgres services in the cloud: enable and tune

io_uringby default- What: Ship a tuned

io_uringbackend withDEFER_TASKRUN, adaptive batching, and per-ring configuration; provide presets for I/O-bound vs. CPU-bound workloads. - Where: Cloud (DBaaS), software (PostgreSQL vendors).

- Why: Immediate, validated throughput improvements (≈10–15%) and reduced CPU overhead for storage-intensive tenants.

- How/tools: Config templates; automation that flips between interrupt-driven and

IOPOLLmodes based on live I/O intensity; monitoring of page-fault ratios and batches-in-flight. - Assumptions/dependencies: Kernel support for

io_uringfeatures; ops teams comfortable with ring separation whenIOPOLLis used.

- What: Ship a tuned

- Distributed analytics engines: unify network and storage I/O for shuffles using

io_uring- What: Replace hybrid epoll+libaio shuffle paths with a single

io_uringpipeline that batches TX/RX and disk ops; use request linking to order send→write sequences; adopt registered buffers to eliminate copies. - Where: Software (MPP engines, distributed SQL, OLAP systems, data warehouses).

- Why: Higher shuffle throughput on 200–400 Gbit/s NICs; lower CPU per message; simplified code paths.

- How/tools: One-ring-per-worker model; multishot operations; registered buffer pools; completion-based scheduling; per-core CQ draining.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Modern NICs and NVMe; Linux with

io_uring; willingness to refactor shuffle operators.

- What: Replace hybrid epoll+libaio shuffle paths with a single

- Fintech/ledger systems requiring fast durable writes

- What: Prefer enterprise NVMe SSDs with DRAM caches and PLP; use NVMe passthrough (

OP_URING_CMD) + explicitflushwhere filesystem constraints permit; avoidO_SYNC(slower than write+fsync); pin I/O workers to local chiplets to shave latency. - Where: Finance (high-volume ledgers, payments), software (TigerBeetle-like systems).

- Why: Microsecond-scale durability with enterprise SSDs; lower jitter; less fsync overhead.

- How/tools: Separate rings for durability when mixing

IOPOLL(since fsync is blocking and incompatible withIOPOLL); device-level flush via passthrough; latency monitors. - Assumptions/dependencies: Raw device access or

O_DIRECTfilesystem support; enterprise SSDs with PLP; workloads tolerant of bypassing higher-level FS abstractions.

- What: Prefer enterprise NVMe SSDs with DRAM caches and PLP; use NVMe passthrough (

- Storage vendors and SREs: latency-safe batching playbooks

- What: Operate with batch sizes that balance throughput vs. tail latency (e.g., 8–32 for write bursts); cap outstanding I/O to avoid SSD queue overload; use adaptive batch controllers tied to ready-fiber counts.

- Where: Industry (storage ops), software (DBMS config).

- Why: Avoids latency spikes (e.g., 200 µs at batch size 128), preserves predictable response time.

- How/tools: “Latency-aware batch controller” libraries; SSD telemetry hooks; feedback-based batch flushing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Visibility into SSD queue depth and IOPS; workload-defined SLOs.

- Backup/restore and ETL pipelines: exploit larger block sizes and registered buffers

- What: Use 128–256 KiB I/O blocks (below hardware/software thresholds) with registered buffers to reach near-PCIe 5 throughput per core; avoid worker fallback thresholds (

max_hw_sectors_kb,nr_requests,max_segments). - Where: Software (backup tools, ETL), industry (data engineering).

- Why: 50–90 GiB/s per-core read/write when bypassing the storage stack; minimal CPU per byte.

- How/tools: Block-size tuning guides; “worker-fallback guardrails” that detect and back off before thresholds;

OP_URING_CMDfor NVMe where feasible. - Assumptions/dependencies: Direct block device access or FS support; kernel and NVMe driver capabilities; alignment with device limits.

- What: Use 128–256 KiB I/O blocks (below hardware/software thresholds) with registered buffers to reach near-PCIe 5 throughput per core; avoid worker fallback thresholds (

- Energy-efficient operations: CPU-cycle-aware I/O planning

- What: Use the paper’s cycle-based model to optimize for lower CPU per I/O through batching, registered buffers, and completion polling; switch off

IOPOLLfor CPU-bound workloads to save cycles. - Where: Industry (cloud cost optimization), energy sector (green IT).

- Why: Measurable CPU savings; reduced power draw for I/O-bound services.

- How/tools: Model-driven I/O tuners; dynamic toggling between polling and interrupts based on I/O density.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Telemetry access; willingness to reconfigure live systems.

- What: Use the paper’s cycle-based model to optimize for lower CPU per I/O through batching, registered buffers, and completion polling; switch off

- Education and research labs: adopt artifacts and microbenchmarks for curricula

- What: Use the open-source artifacts to teach completion-based I/O, fiber scheduling, batching effects, and modeling; replicate the YCSB/TPC-C analyses.

- Where: Academia (OS/DB courses), software (research prototypes).

- Why: Practical exposure to modern Linux I/O; reproducible performance studies.

- How/tools: Artifact repo; lab scripts; cycle-count instrumentation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Linux lab environment; NVMe/NIC access for advanced exercises.

- Ops policies: procurement guidance for SSDs and OS configurations

- What: Prefer enterprise SSDs with PLP; ensure kernels with

DEFER_TASKRUNand recentio_uringpatches; provision raw-block devices for I/O-critical tenants; reserve cores forSQPOLLwhen beneficial. - Where: Policy (IT procurement, platform engineering).

- Why: Avoids fsync pathologies; unlocks powerful

io_uringfeatures safely. - How/tools: Standard operating procedures; compatibility matrices; core allocation playbooks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational willingness to differentiate tiers by device class; kernel policy governance.

- What: Prefer enterprise SSDs with PLP; ensure kernels with

Long-Term Applications

The following items require further R&D, scaling, or ecosystem changes to reach broad adoption. They build on the paper’s insights about architecture, tuning, and workload-aware design.

- Asynchronous, filesystem-backed durability APIs

- What: Kernel support for true non-blocking

fsyncor equivalent asynchronous durability semantics; unified withIOPOLLrings. - Where: Software (Linux kernel, filesystems), industry (DBMS vendors).

- Why: Eliminates current worker-thread fallbacks; simplifies durable write paths.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Kernel and FS evolution; careful safety semantics.

- What: Kernel support for true non-blocking

- Filesystem integration for NVMe passthrough

- What: Standardized passthrough paths (e.g.,

OP_URING_CMD) usable over mainstream filesystems without forcingO_DIRECTor raw devices. - Where: Software (FS developers), industry (storage vendors).

- Why: Gains of passthrough (20%+ throughput) with FS convenience; broader adoption.

- Assumptions/dependencies: FS design changes; security and sharing considerations.

- What: Standardized passthrough paths (e.g.,

- Self-tuning, model-driven I/O orchestration

- What: Controllers that learn per-workload page-fault rates, compute costs, and device thresholds to auto-tune batching, block sizes, polling modes, and ring layouts.

- Where: Software (DBMS internal tuning), academia (systems research).

- Why: Sustained near-optimal performance across diverse workloads without manual tuning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable telemetry; Bayesian/ML controllers; guardrails for tail latency.

- Unified

io_uringshuffle libraries for distributed engines- What: Reusable libraries that implement high-throughput, all-to-all shuffles with unified storage and network I/O, registered buffers, and request linking.

- Where: Software (Spark-like engines, distributed SQL systems).

- Why: Drop-in improvements for parallel joins and repartitions; codebase simplification.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ecosystem buy-in; NIC/SSD support; portability across kernels.

- Cooperative concurrency throughout DBMS stacks

- What: Wide adoption of coroutine/fiber-based runtimes that coordinate with

io_uringcompletion queues; lock-free internal data structures tolerant of resume-after-I/O. - Where: Software (DBMS architectures), academia (new concurrency control schemes).

- Why: Large throughput gains without traditional locking; cleaner I/O overlaps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Significant refactoring; rigorous correctness proofs.

- What: Wide adoption of coroutine/fiber-based runtimes that coordinate with

- Container and multi-tenant fairness for polling modes

- What: Orchestrators that safely expose

SQPOLL/IOPOLLin containers with fair core reservations and isolation; cgroup-level accounting for rings. - Where: Industry (cloud platforms, Kubernetes), policy (multi-tenant fairness).

- Why: Unlocks polling benefits without starving co-located services.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scheduler integration; ops standards for core pinning.

- What: Orchestrators that safely expose

- Energy-aware schedulers that co-design CPU, NIC, and NVMe utilization

- What: Schedulers that minimize CPU wakeups, choose between interrupts and polling, and optimize batching for energy per transaction.

- Where: Energy sector (green computing), industry (cost/SLA trade-offs).

- Why: Reduces power and carbon footprint at scale; meets SLOs efficiently.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cross-layer telemetry; incentive to prioritize energy outcomes.

- Flash-optimized DBMS designs with native NVMe command paths

- What: End-to-end architectures that assume direct NVMe command usage, prioritize large block operations, and avoid FS overhead in I/O-critical components (e.g., WAL, checkpoints).

- Where: Software (next-gen OLTP/OLAP DBMS), academia (system design).

- Why: Stable microsecond-level durability and high throughput with simplified I/O stacks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ops comfort with raw devices; robust failure handling.

- Cross-stack zero-copy networking and storage

- What: Extended registered-buffer support across NICs and NVMe devices to enable true zero-copy TX/RX and DMA into user memory for mixed net+storage pipelines.

- Where: Software (OS and driver ecosystems), robotics/edge (real-time pipelines).

- Why: Further reduces CPU per I/O; improves latency and jitter.

- Assumptions/dependencies: NIC-driver and kernel feature convergence; security constraints.

- Standards and procurement policies for high-performance I/O readiness

- What: Enterprise guidelines that mandate PLP SSDs, recent kernels, and

io_uringfeature readiness for I/O-sensitive applications; tiers for raw-block access. - Where: Policy (enterprise IT, cloud platform standards).

- Why: Ensures deployments can benefit from

io_uringoptimizations without ad-hoc exceptions. - Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational alignment; risk management for raw device usage.

- What: Enterprise guidelines that mandate PLP SSDs, recent kernels, and

- Developer tooling: ring managers, batch controllers, and latency profilers

- What: Tooling to visualize CQ/SQ activity, detect worker fallbacks, and predict throughput from cycle models; libraries to enforce safe batch-size ranges and block-size ceilings.

- Where: Software (devops tooling, performance engineering).

- Why: Makes

io_uringperformance accessible to non-experts; reduces tuning time. - Assumptions/dependencies: Maintained OSS tools; kernel metrics access.

- Query planners aware of I/O mode costs

- What: Planners that choose operator shapes (e.g., scan block sizes, shuffle fan-out) based on estimated CPU cycles per I/O and latency variance under current ring configuration.

- Where: Software (DBMS optimizers), academia (cost models).

- Why: Better end-to-end performance with dynamic I/O-aware optimization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Integration between runtime telemetry and optimizer; robust models.

- Safer multi-tenant sharing of passthrough and polling features

- What: Mechanisms to expose passthrough commands and polling to tenants while preserving isolation and fairness (e.g., device queue partitioning, per-tenant IO depth caps).

- Where: Industry (cloud storage), policy (tenant isolation requirements).

- Why: Expands adoption of high-performance paths beyond single-tenant instances.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware/driver support for partitioning; cloud governance.

- Formal verification and testing frameworks for cooperative I/O correctness

- What: Tools to prove correctness of fiber-based DBMS operations that can resume after I/O delays (e.g., restartable B-tree traversals) and ensure isolation without locks.

- Where: Academia (verification), software (mission-critical DBMS).

- Why: Confidence in large architectural changes; safer adoption in regulated sectors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Research investment; integration into CI/CD pipelines.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.