FALCON: Actively Decoupled Visuomotor Policies for Loco-Manipulation with Foundation-Model-Based Coordination (2512.04381v1)

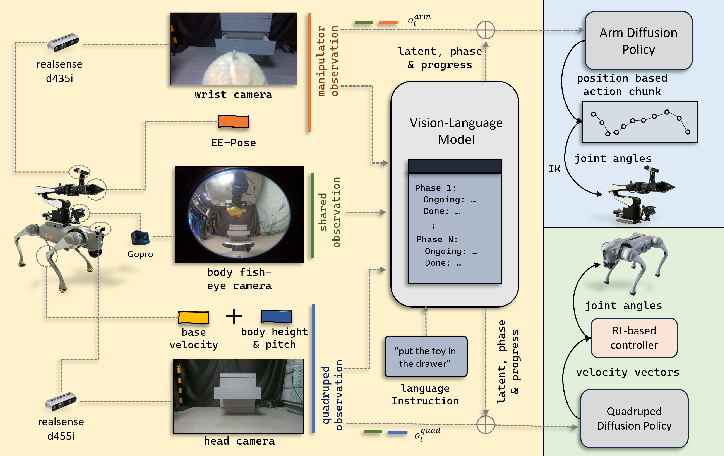

Abstract: We present FoundAtion-model-guided decoupled LoCO-maNipulation visuomotor policies (FALCON), a framework for loco-manipulation that combines modular diffusion policies with a vision-language foundation model as the coordinator. Our approach explicitly decouples locomotion and manipulation into two specialized visuomotor policies, allowing each subsystem to rely on its own observations. This mitigates the performance degradation that arise when a single policy is forced to fuse heterogeneous, potentially mismatched observations from locomotion and manipulation. Our key innovation lies in restoring coordination between these two independent policies through a vision-language foundation model, which encodes global observations and language instructions into a shared latent embedding conditioning both diffusion policies. On top of this backbone, we introduce a phase-progress head that uses textual descriptions of task stages to infer discrete phase and continuous progress estimates without manual phase labels. To further structure the latent space, we incorporate a coordination-aware contrastive loss that explicitly encodes cross-subsystem compatibility between arm and base actions. We evaluate FALCON on two challenging loco-manipulation tasks requiring navigation, precise end-effector placement, and tight base-arm coordination. Results show that it surpasses centralized and decentralized baselines while exhibiting improved robustness and generalization to out-of-distribution scenarios.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces FALCON, a way to control a walking robot with an arm (a legged “mobile manipulator”) so it can move around and use its hand to do tasks like grabbing or placing objects. The key idea is to split the robot’s brain into two parts: one part focuses on moving the body (locomotion), and the other focuses on moving the arm (manipulation). A large vision-LLM (like CLIP, which understands images and text) then acts like a smart coordinator that keeps both parts working together toward the same goal.

What is the paper trying to figure out?

The authors ask:

- Can we make walking-and-grabbing tasks easier and more reliable by giving the robot two separate minds: one for moving and one for handling objects?

- If we separate these minds, how do we make sure they still cooperate smoothly?

- Can a big pre-trained model that understands images and text (a “foundation model”) help the two parts share the same understanding of the task?

- Can we teach the system to know what stage of a task it’s in (like “approach,” “grab,” “place”) using simple text descriptions, without needing humans to label every step?

How did they do it?

They use a few building blocks and connect them in a simple, smart way:

Decoupled control (two specialists)

Think of the robot like a person: your legs help you walk, and your hands help you manipulate things. FALCON creates:

- A locomotion policy (the “legs” expert) that outputs high-level commands like “move forward,” “turn,” or “raise the body.”

- A manipulation policy (the “arm” expert) that outputs target hand positions, like “move the gripper here.”

Each expert looks at the information it needs most, instead of both trying to understand everything at once. This reduces confusion and makes each part more reliable.

A foundation model as the coordinator

They use CLIP, a vision-LLM trained on huge amounts of image–text data. CLIP:

- Takes the robot’s camera images, the robot’s own body state (its “self-sense,” called proprioception), and the user’s instruction (like “pick up the red mug and place it on the table”).

- Produces a compact “shared summary” (called a latent embedding). This is like a short bullet-point plan both the legs and arm can read.

This shared summary helps both experts cooperate without forcing them to share raw camera feeds or low-level features.

Cameras and inputs

The robot uses only RGB cameras (no depth sensors), with three views:

- Wrist camera: close-up view of the hand and objects.

- Body camera: a wide view of the robot’s posture and nearby space.

- Head camera: a lower-angle look at the workspace to guide the base while approaching.

Using multiple camera angles helps the robot see both the big picture and the fine details.

Low-level locomotion controller

Under the hood, the legs have a low-level controller trained in simulation with reinforcement learning (using PPO). It turns high-level commands (like “go faster,” “pitch the body,” “raise height”) into safe joint movements. This makes walking more stable and reduces the chance of falling over, even though the high-level commands are based only on camera images.

Diffusion policies (how actions are generated)

Both the legs and arm use “diffusion policies,” a modern way to generate actions:

- Imagine you scribble a noisy plan and then “denoise” it step by step until you get a clean, reasonable action.

- This helps the robot handle uncertainty and produce smooth movements over time.

The arm’s high-level outputs are hand positions. An “inverse kinematics” solver then figures out the exact joint angles needed to put the hand there—like calculating how to bend your elbow and shoulder to touch your nose.

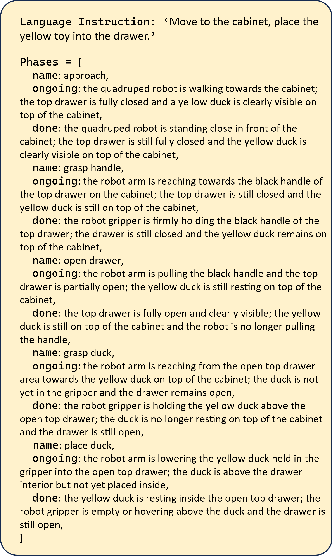

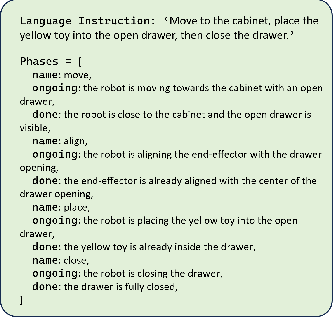

Understanding task stages (phase-progress head)

The system reads simple text descriptions of task stages (like “approach the drawer,” “grasp the handle,” “pull”) and, together with images and robot state, estimates:

- Which phase it’s currently in (discrete stage).

- How far along it is within that phase (continuous progress).

Importantly, it learns this without needing humans to mark the phase in every training example.

Keeping the legs and arm in sync (contrastive alignment)

They add a learning signal called “contrastive loss,” which is like teaching:

- “Good pairs” (leg and arm actions that belong together for the current situation) should be close in the shared summary space.

- “Bad pairs” (leg and arm actions mismatched from different situations) should be far apart.

This trains the shared summary to reflect whether leg and arm movements are compatible.

What did they find?

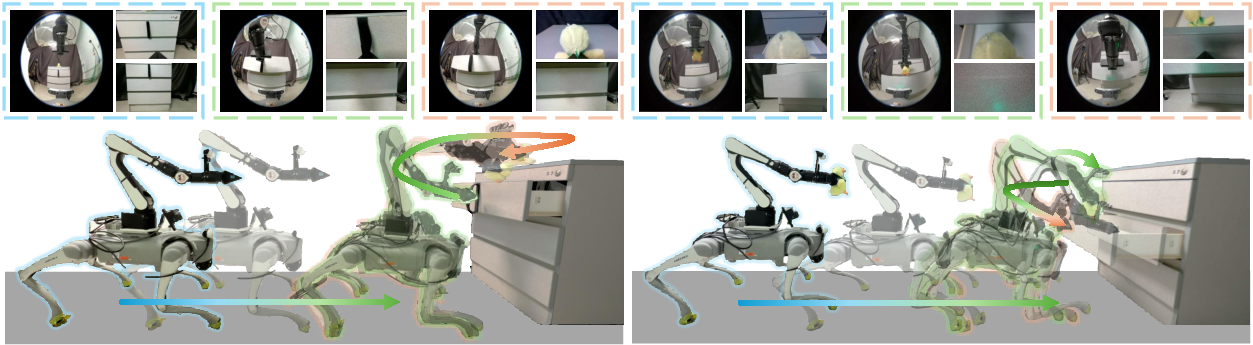

Across two challenging tasks that require:

- Long-distance navigation,

- Precise hand placement,

- Tight timing between base movement and arm manipulation,

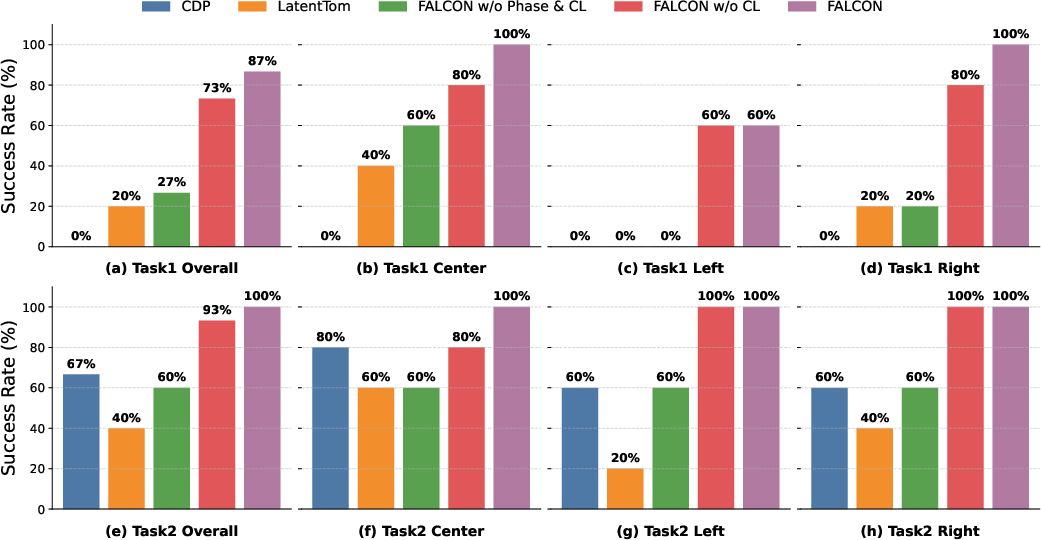

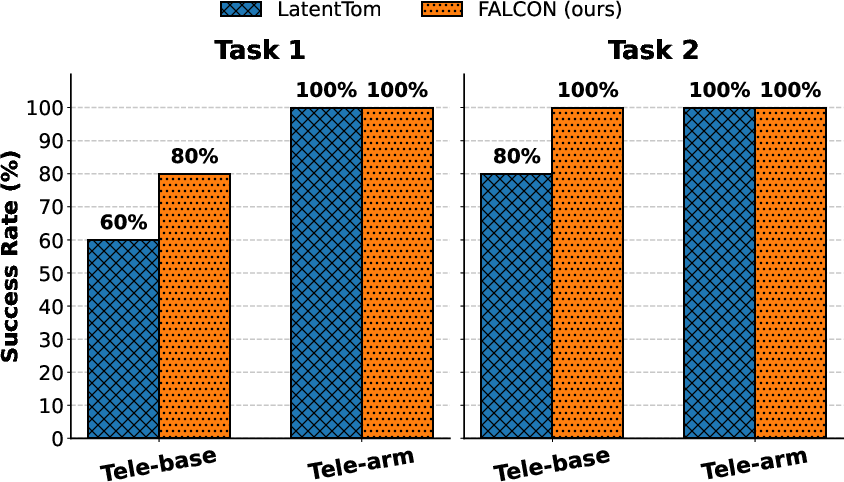

FALCON:

- Worked better than methods that try to control the whole body with one big policy (centralized).

- Worked better than methods that separate parts but don’t coordinate them well (decentralized without a good shared summary).

- Was more robust when situations changed unexpectedly (out-of-distribution), like different lighting or clutter.

- Generalized better to new scenes compared to the baselines.

Why is this important?

- Splitting the problem into two specialists makes training easier and performance stronger, especially for tricky walking robots that must stay stable while using their arm.

- Using a foundation model (like CLIP) as a shared coordinator is a simple, reusable idea: you don’t need to train a giant end-to-end controller; you can plug in a strong pre-trained model to align sub-policies.

- The phase-progress head helps the robot keep track of where it is in a long task using plain language descriptions, which makes the system more understandable and easier to guide.

- Because the locomotion and manipulation are separate, a human operator can take over one part (like moving the base manually) while the other part (the arm) still works.

In short, FALCON shows a practical and powerful way to build general-purpose robots: let specialized parts do what they’re best at, and use a shared, language-aware summary to keep them coordinated. This could help future robots perform complex household and industrial tasks more reliably, even in messy, changing environments.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to be actionable for future research.

- When and why decoupling helps: No formal analysis or systematic paper of the conditions under which actively decoupled policies outperform monolithic whole-body controllers (e.g., task complexity, observation heterogeneity, dynamics regimes, training data coverage).

- Coordination channel sufficiency: Unclear whether a CLIP-derived latent is necessary or sufficient for effective coordination; lacks comparisons to learned consensus spaces without CLIP, alternative VLMs/LLMs, or hybrid coordinators combining semantics with constraints.

- Prompt sensitivity: No evaluation of sensitivity to language prompt design, phase descriptions, or paraphrases; robustness to ambiguous or erroneous instructions remains untested.

- Phase-progress head validation: Missing quantitative evaluation of phase classification and progress regression accuracy, ablations showing its causal contribution to performance, and sensitivity to mis-specified or incomplete phase text descriptions.

- Encoding proprioception via CLIP: The approach “uses CLIP to encode proprioception” via projectors, but it is unclear how well non-visual states are represented; no comparison to dedicated state encoders or multimodal backbones designed for proprioceptive inputs.

- Contrastive loss specification and efficacy: The coordination-aware contrastive loss is under-specified (negative sampling strategy, temperature, weighting, margin); lacks evidence that distances in the learned space predict arm–base action compatibility or improve coordination beyond baselines.

- Hard negatives and temporal structure: Negative pairs are formed by shuffling across samples, but no exploration of harder negatives (semantically similar yet incompatible actions) or cross-temporal mismatches; impact on avoiding spurious correlations is unknown.

- Decentralized execution in practice: The paper claims decentralized compatibility “in principle” but does not evaluate synchronization, communication latency, stale embeddings, or policy drift when subsystems run on separate compute nodes.

- Multi-camera robustness: No ablation of the tri-camera setup; robustness to occlusion, partial camera failure, calibration drift, or varied camera placements/FOVs is not studied.

- RGB-only sensing trade-offs: Effect of adding depth (RGB-D), stereo, or learned monocular depth on navigation stability and manipulation precision is unquantified; failure modes in texture-poor, reflective, or low-light scenes remain unexplored.

- Open-loop base control drift: Open-loop velocity commands may accumulate error over long horizons; missing metrics on cumulative pose drift, recovery behaviors, and comparisons to closed-loop navigation (e.g., visual odometry, SLAM).

- Embodiment generalization: Unknown transfer to different legged platforms, arm kinematics/DoFs, wheeled bases, or humanoids; what retraining/tuning is required for new embodiments?

- Dataset scale and efficiency: No reporting of dataset size/diversity, sample efficiency of diffusion training, or compute/latency budgets; unclear performance scaling with number of demonstrations and environments.

- Safety and failure taxonomy: Missing systematic analysis of failure modes (collisions, tipping, IK singularities, payload changes) and corresponding detection/recovery strategies; no safety validation under adversarial or degraded conditions.

- Dynamic environments and terrain: Evaluation is limited to two tasks; robustness to moving obstacles, crowds, uneven terrain, stairs, and perturbations is untested.

- Domain randomization coverage: While domain randomization is applied, there is no measurement of which randomization dimensions most affect sim-to-real transfer or where randomization fails to cover real-world distributions.

- Contact/force control: Manipulation relies on position control with IK; tasks requiring force/impedance control, frictional contacts, and compliant interactions (e.g., door opening with variable resistance) are not addressed.

- Constraint-aware coordination: Coordination relies on semantic latents, but no integration of explicit kinematic/manipulability constraints, reachability, or visibility constraints; unclear benefits of combining semantic coordination with constraint-aware planning.

- Coordination metrics: Lacks standardized metrics for coordination quality (e.g., base–arm compatibility score, phase transition accuracy, mutual predictability), and correlation with task success rates.

- Language robustness: No experiments probing instruction complexity (multi-step goals, negations, references), ambiguity resolution, or recovery from incorrect user language.

- Real-time performance: Missing end-to-end timing (inference latency, control frequencies of diffusion and low-level controllers), and deployability on embedded hardware under power/compute constraints.

- Human-in-the-loop takeover: The paper states decoupling allows easy human takeover, but there is no implemented arbitration policy, quantitative assessment of handoff latency, or safety guarantees during transition.

- OOD generalization claims: Out-of-distribution robustness is claimed but not benchmarked across well-defined axes (lighting, object categories, furniture layouts, camera perturbations); standardized OOD tests and metrics are needed.

- Interpretability of the shared latent: No analysis of whether latent dimensions capture phases/goals or predict success; tools for probing, visualizing, or constraining the embedding (e.g., concept activation vectors) are absent.

- Hierarchical memory/planning: Long-horizon tasks likely benefit from memory or high-level planning; integration with planners (e.g., LLM plans, task graphs) or recurrent memory modules is not investigated.

- Resource and reproducibility details: Architecture specifics (projectors, diffusion heads), training hyperparameters, and evaluation protocols are incomplete (paper truncates); releasing code, models, and datasets is necessary for replication.

Glossary

- 6-DoF: Six degrees of freedom, typically referring to full 3D position and orientation control in robotics. "PerAct further extends this idea to 6-DoF control by encoding RGB-D inputs and goal texts with a Perceiver Transformer,"

- affordance value functions: Learned functions estimating the feasibility or utility of actions given the robot’s capabilities and environment. "and then applies learned affordance value functions to filter out infeasible actions."

- affordances: Action possibilities that an environment offers to an agent or robot, given its embodiment and skills. "Approaches such as SayCan couple LLM-based reasoning with robot affordances:"

- behavior-clone diffusion policy: A diffusion-based policy trained via behavior cloning to imitate expert demonstrations. "by using a behavior-clone diffusion policy as high-level guidance, replacing traditional teleoperation inputs."

- chain-of-thought reasoning: A technique where models generate intermediate steps to improve reasoning and planning. "employ chain-of-thought reasoning to infer intermediate steps,"

- CLIP: A vision–LLM that learns joint image–text representations, enabling open-vocabulary perception and semantic alignment. "CLIP~\cite{radford2021learning}, a widely used vision-LLM pre-trained on internet-scale imageâtext pairsâto encode global RGB observations, proprioceptive robot states, and natural language task specifications into a shared latent embedding."

- CLIPFields: A method integrating CLIP features into 3D reconstructions to produce semantically meaningful maps. "CLIPFields integrates CLIP features into 3D reconstructions, achieving semantically meaningful 3D maps"

- CLIPort: A manipulation framework that combines CLIP’s semantic embeddings with spatial reasoning for language-conditioned pick-and-place. "Early approaches such as CLIPort combine CLIPâs pretrained semantic representations with spatial pathway to execute a variety of language-specified pick-and-place tasks in both simulation and the real world."

- consensus channel: A shared communication or representation pathway used to align independent policies. "as the consensus channel,"

- consensus representation: A shared latent that encodes information agreed upon across subsystems to enable coordination. "which learns a consensus representation by sheaf-theoretic consistency losses from scratch,"

- contrastive loss: A learning objective that pulls matched pairs together and pushes mismatched pairs apart in embedding space. "we incorporate a coordination-aware contrastive loss that explicitly encodes cross-subsystem compatibility between arm and base actions."

- decentralized diffusion architectures: Multi-agent diffusion-based control frameworks where policies coordinate via shared embeddings without centralized control. "Recent advances in decentralized diffusion architectures have shown that coordination can emerge through consensus embeddings formed during training"

- diffusion policy: A control policy that models action trajectories via a learned denoising diffusion process. "a diffusion policy produces high-level velocity and pose commands:"

- domain randomization: Training technique that randomizes environment and dynamics parameters to improve robustness and transfer. "domain randomization is applied during training,"

- Ego4D: A large-scale egocentric video dataset used to pretrain temporal encoders for embodied tasks. "pretrained on large-scale video corpora like Ego4D,"

- end-effector: The tool or gripper at the end of a robot arm used to interact with objects. "a high-level end-effector position policy for the arm."

- flow-matching: A generative modeling approach used to train action decoders by matching probability flows, related to diffusion methods. "a flow-matching or diffusion-based action decoder outputs whole-body motor commands."

- foundation models for robotics: Large pretrained multimodal models providing transferable representations for perception, language, and control. "Foundation models for robotics, such as , GR00T N1, Helix, and LBMs, typically adopt an end-to-end vision-language-action formulation"

- inverse kinematics (IK): The process of computing joint configurations that achieve a desired end-effector pose. "converted to joint targets through an inverse-kinematics (IK) solver"

- inter-limb coordination: The coupled control and timing between multiple limbs or manipulators to achieve stable and dexterous behavior. "inter-limb coordination~\cite{zhu2025versatile, yang2025helom}"

- Latent Theory of Mind (LatentToM): A decentralized manipulation approach that structures latent spaces to improve coordination among agents. "Recent work on Latent Theory of Mind (LatentToM)~\cite{he2025latent} shows that, in pure manipulation settings, decentralizing control and explicitly structuring latent spaces into ego and consensus components can improve robustness and coordination among multiple arms."

- latent embedding: A compact learned representation capturing task and scene context for conditioning policies. "shared latent embedding that conditions both subsystems."

- latent space: The abstract representation space where embeddings capture semantic and task-relevant structure. "To further structure the latent space, we incorporate a coordination-aware contrastive loss"

- loco-manipulation: The combined problem of controlling locomotion and manipulation jointly within a single robotic platform. "However, loco-manipulation, jointly controlling a mobile base and one or more arms, remains especially challenging on legged platforms"

- Markov Decision Process (MDP): A formalism for sequential decision-making defined by states, actions, transitions, rewards, and discount. "The training of the low-level controller is formulated as a Markov Decision Process (MDP),"

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): An optimization-based control strategy that solves a finite-horizon problem repeatedly to track objectives. "Examples range from model-based whole-body MPC for legged mobile manipulators"

- multi-contact planning: Planning motions that leverage multiple simultaneous contacts for stability and manipulation. "multi-contact planning~\cite{sleiman2023versatile}"

- open-loop: Control where actions are issued without real-time feedback corrections over the execution horizon. "which are executed in an open-loop manner."

- open-set detector: A perception system that can detect objects beyond a fixed set of known categories. "functions as an open-set detector"

- open-vocabulary detectors: Detectors leveraging vision–language embeddings to identify categories not seen during training. "open-vocabulary detectors such as Detic, OWL-ViT, and ViLD"

- out-of-distribution (OOD): Conditions that differ from the training data, often causing performance degradation. "out-of-distribution (OOD) scenarios."

- PaLM-E: A multimodal embodied LLM that integrates visual, proprioceptive, and linguistic inputs for planning. "PaLM-E interleaves multimodal input to generate sequential plans."

- Perceiver Transformer: A Transformer architecture for multimodal inputs, used here for manipulation and language conditioning. "by encoding RGB-D inputs and goal texts with a Perceiver Transformer,"

- proprioceptive states: Internal sensor measurements (e.g., joint positions, velocities) describing the robot’s own body state. "proprioceptive states"

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): A popular reinforcement learning algorithm that optimizes policies with clipped updates for stability. "optimized using the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)"

- receding-horizon planners: Planners that optimize over a finite prediction window and replan at each step. "relatively slow receding-horizon planners."

- R3M: A temporal visual encoder pretrained on large video datasets to improve manipulation with limited demonstrations. "Temporal encoders such as R3M, pretrained on large-scale video corpora like Ego4D,"

- SAM: Segment Anything Model; a prompt-driven segmentation model that generalizes across categories. "SAM provides prompt-driven, category-agnostic segmentation that functions as an open-set detector"

- sheaf-theoretic: Relating to sheaf theory, used here to impose consistency constraints over learned representations. "sheaf-theoretic consistency losses"

- sim-to-real transfer: Techniques and practices to ensure policies trained in simulation perform well on real robots. "To enhance sim-to-real transfer and operational robustness,"

- temporal encoders: Models that capture time-dependent visual features to improve control in dynamic settings. "Temporal encoders such as R3M"

- vision-language-action (VLA) model: A model that jointly processes vision and language to output action commands. "Figureâs Helix vision-language-action (VLA) model"

- vision-LLM (VLM): A model that aligns visual and textual modalities into a shared representation. "The VLM encodes global scene context, proprioceptive states, and goal instructions into a shared latent embedding that conditions both subsystems."

- visuomotor policy: A policy mapping visual inputs to motor actions for robotic control. "visuomotor policies"

Practical Applications

Overview

FALCON introduces a deployable architecture for legged mobile manipulation that actively decouples locomotion and manipulation into two specialized diffusion-based visuomotor policies, coordinated via a shared latent embedding produced by a frozen vision–language foundation model (CLIP). Key innovations include:

- Foundation-model-guided coordination through a compact shared latent that aligns otherwise independent base and arm policies.

- A phase-progress head that infers discrete task phases and continuous progress from textual descriptions without manual phase annotations.

- A coordination-aware contrastive loss that encodes cross-subsystem compatibility (arm–base) in the latent space.

- A tri-camera, RGB-only, multi-view perception stack and a simulation-trained low-level RL locomotion controller that stabilizes a legged base while tracking high-level velocity/pose commands.

Below are practical applications derived from these findings, organized by immediacy, with sectors, enabling tools/workflows, and assumptions/dependencies noted.

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be pursued with modest integration and validation, leveraging available legged hardware (e.g., Spot, ANYmal, Unitree), existing RGB cameras, and modern GPU/embedded compute.

- Legged mobile manipulation in facilities with stairs and cluttered terrain

- Sector: Robotics, Facilities Operations, Construction, Energy, Industrial Inspection

- Use cases:

- Door and drawer operations on multi-level sites; turning valves, pressing buttons, flipping switches.

- Navigating mezzanines, catwalks, and staircases to position the end-effector for inspection or light intervention (e.g., resetting breakers).

- Tool pickup/placement and simple reconfiguration tasks in labs or workshops when wheeled platforms are constrained by terrain.

- Tools/workflows:

- Decoupled diffusion policies for base velocity/pose and arm end-effector control.

- CLIP-based coordinator microservice that produces the shared latent z_t from multi-view RGB and task text.

- Low-level RL locomotion controller (trained in simulation with domain randomization) that tracks commanded velocity, pitch, and height.

- ROS 2 nodes for the “base policy,” “arm policy,” “CLIP coordinator,” and “IK solver,” plus safety monitors.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Reliable legged platform and stable IK for the arm; tri-camera RGB setup with sufficient coverage.

- Adequate on-board compute (GPU/TPU) for diffusion inference and CLIP embedding in real time.

- Safety interlocks for open-loop velocity; site lighting adequate for RGB-only perception.

- Shared-autonomy teleoperation with partial human takeover

- Sector: Robotics, Public Safety/Disaster Response, Industrial Maintenance

- Use cases:

- Operator controls either the base or the arm while the other subsystem runs FALCON, accelerating task completion and reducing operator load.

- Safe intervention/handoff when either subsystem faces ambiguous observations or fails to generalize.

- Tools/workflows:

- Human-in-the-loop UI for subsystem override; policy isolation ensures clean handoff.

- CLIP latent keeps the autonomous subsystem task-aligned even when the other is human-driven.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Robust network links for teleop; clear escalation/de-escalation protocol; operator training.

- Phase-aware task monitoring and supervision for long-horizon behaviors

- Sector: Software/MLOps for Robotics, Quality Assurance, Compliance

- Use cases:

- On-robot phase and progress indicators for monitoring complex workflows (e.g., “approach target,” “align,” “grasp,” “place”), enabling live dashboards and alerts.

- Reduced annotation burden in dataset creation by using textual phase descriptions instead of manual labels.

- Tools/workflows:

- Phase-progress head plugged into CLIP encoder; prompt library of phase descriptions per task.

- Logging/telemetry integration that records phase scores and progress for audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Carefully crafted phase prompts; validation to avoid misleading progress indicators.

- RGB-only multi-view perception stack for cost-effective mobile manipulation

- Sector: Robotics Hardware/Perception, Education/Academia

- Use cases:

- Deployable camera-only control stack for pick-and-place and simple tool use under clutter with reduced hardware complexity.

- Teaching labs and research prototypes replacing depth sensors with multi-view RGB and foundation-model features.

- Tools/workflows:

- Wrist/body/head camera configuration; CLIP-based feature extraction; data collection pipeline with multi-view sync.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Good lighting and texture; occlusion management via camera placement; acceptable accuracy from 2D cues.

- Rapid prototyping of decoupled control stacks for legged platforms

- Sector: Robotics Integrators, Startups, Academia

- Use cases:

- Evaluate decoupled vs monolithic whole-body policies on new tasks and robots with a modular architecture.

- Mix-and-match: swap in different low-level locomotion controllers or IK solvers without retraining the other subsystem.

- Tools/workflows:

- FALCON-style SDK: policy interfaces, CLIP coordinator adapters, contrastive alignment training scripts, ROS 2 integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to trajectory datasets for arm/base; computing resources for diffusion training; standardized action/observation APIs.

- Improved robustness to out-of-distribution conditions and observation mismatches

- Sector: Field Robotics, Industrial Operations

- Use cases:

- Deploy decoupled policies to mitigate failure cascades when either the base or the arm encounters OOD conditions (e.g., unexpected terrain or occlusions).

- Separate compute execution for policies, coordinated by a common latent, to increase fault tolerance.

- Tools/workflows:

- Contrastive loss training that enforces arm–base action compatibility; separate inference processes connected to the same latent stream.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Robustness depends on training coverage and domain randomization; ongoing validation in target environments.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling of models and datasets, or deeper systems engineering and regulatory development.

- Generalist legged mobile manipulators for household assistance

- Sector: Daily Life, Elder Care, Domestic Services

- Use cases:

- Fetch-and-deliver across floors, door/drawer operations, setting tables, tidying spaces with user language prompts.

- Adaptive repositioning of the base to optimize manipulability (e.g., crouching, body re-centering) in tight home environments.

- Dependencies:

- Larger-scale training data across homes; safety certification; reliable on-device inference; better handling of diverse lighting and clutter.

- Foundation-model coordination across multiple subsystems and embodiments

- Sector: Robotics (Humanoids, Dual-Arms, Mobile Platforms)

- Use cases:

- CLIP-like coordination of two arms + mobile base + body posture modules; extension to humanoids and wheeled bases.

- Multi-robot coordination: legged platform positions objects; aerial robot inspects; arm performs manipulation, all aligned by a shared semantic latent.

- Products/workflows:

- “Coordination-as-a-Service” middleware that provides shared task latents to multiple agents; standardized consensus embedding interfaces.

- Dependencies:

- Scalable cross-embodiment datasets; timing/latency management; robust multi-agent safety protocols.

- Phase-aware, language-grounded planners that fuse LLM reasoning with decoupled control

- Sector: Software/Planning, Education, Policy/Compliance

- Use cases:

- LLM generates phase-aware plans and prompts; FALCON executes with progress feedback loops; interpretable audit trails for safety-critical tasks.

- Curriculum learning and training pipelines that auto-generate phase descriptions and adapt plans online.

- Products/workflows:

- Planning stack that couples chain-of-thought LLMs to phase-progress heads and diffusion policies; auditing tools that log per-phase compliance.

- Dependencies:

- Robust grounding from high-level plans to low-level actions; handling language ambiguities; compute budgets.

- Safety, certification, and regulatory frameworks for decoupled, foundation-model-driven robots

- Sector: Policy/Standards, Insurance/Risk

- Use cases:

- New test suites focusing on subsystem isolation, failover, and interpretable phase progression.

- Liability and assurance models for foundation-model embeddings that influence action without being the policy itself.

- Products/workflows:

- Compliance checklists, scenario catalogs, and conformance tests; audit APIs exposing phase scores and action compatibility metrics.

- Dependencies:

- Industry–academia–regulator coordination; standardization of telemetry and logs; third-party audits.

- Scaled data generation and synthetic training for robust coordination

- Sector: Software/Simulation, Robotics R&D

- Use cases:

- Synthetic video and trajectory generation (e.g., language-conditioned video world models) to populate varied arm–base interaction distributions.

- Automatic creation of negative arm–base pairs to strengthen contrastive alignment and OOD robustness.

- Products/workflows:

- Dataset builders; contrastive pair generators; domain randomization suites; sim-to-real transfer toolchains.

- Dependencies:

- High-fidelity simulators; validated bridging techniques; compute for large-scale diffusion and VLM training.

- Enhanced multimodal sensing and control beyond RGB-only

- Sector: Robotics Hardware/Perception

- Use cases:

- Integrate depth, tactile, force sensing, and body posture modulation to further improve precision and safety.

- Adaptive control switching between velocity and position regimes based on uncertainty estimates from diffusion policies.

- Products/workflows:

- Sensor fusion modules; uncertainty-aware controllers; auto-tuning pipelines for switching control modes.

- Dependencies:

- Hardware integration; recalibration of policies; retraining with multimodal data.

- Distributed, edge–cloud execution for large models in real time

- Sector: Software/Cloud Robotics, Infrastructure

- Use cases:

- Running decoupled policies on separate compute units (arm controller on edge; base controller on-board; coordinator on local server) with synchronized latents.

- Fleet operations: centralized coordinator dispatches phase-aware goals to many robots.

- Products/workflows:

- Low-latency transport for shared latents; schedulers; observability stacks; fleet safety monitors.

- Dependencies:

- Deterministic timing and bandwidth; robust fallback when connectivity degrades; cyber-security hardening.

Notes on Assumptions and Dependencies

- Hardware/platform

- Legged base with a mounted arm; stable IK solver; adequate battery and payload handling; reliable tri-camera RGB setup.

- Perception and environment

- RGB-only constraints require good lighting and sufficient texture; occlusion management via multi-view camera placement.

- Compute and software

- Real-time diffusion and CLIP inference; ROS 2 integration; safety monitors for open-loop velocity; domain randomization coverage for sim-to-real.

- Data and training

- Representative trajectories for both subsystems; curated phase descriptions; negative arm–base pairs for contrastive loss; OOD scenarios included.

- Safety and compliance

- Interpretable phase-progress for audits; subsystem isolation and human-in-the-loop controls; adherence to site safety standards.

- Scalability and generalization

- Cross-embodiment extensions, multi-robot coordination, and standardized consensus latents require larger datasets and stronger validation.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.