VLA Models Are More Generalizable Than You Think: Revisiting Physical and Spatial Modeling (2512.02902v1)

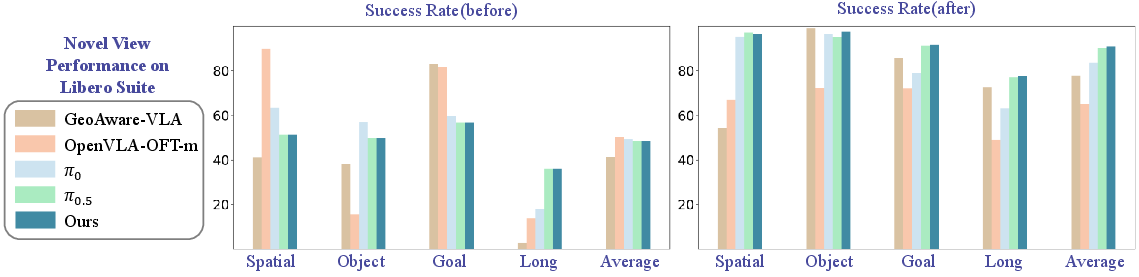

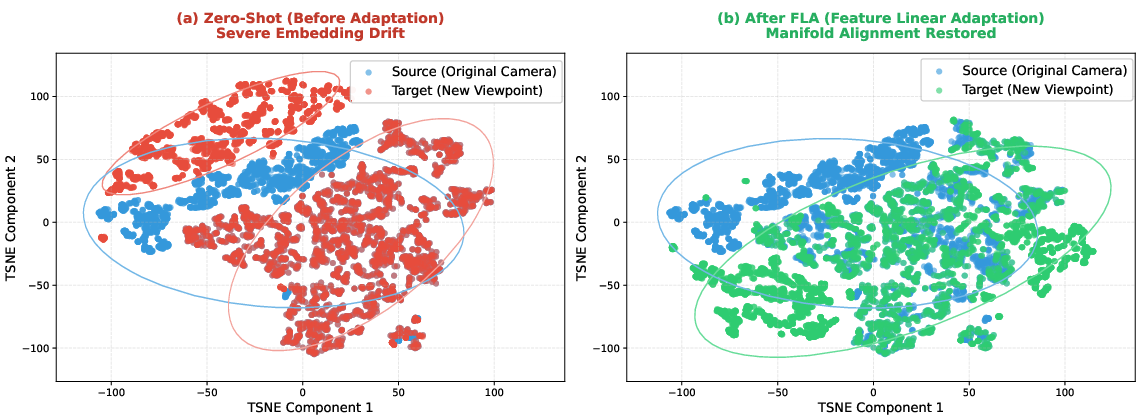

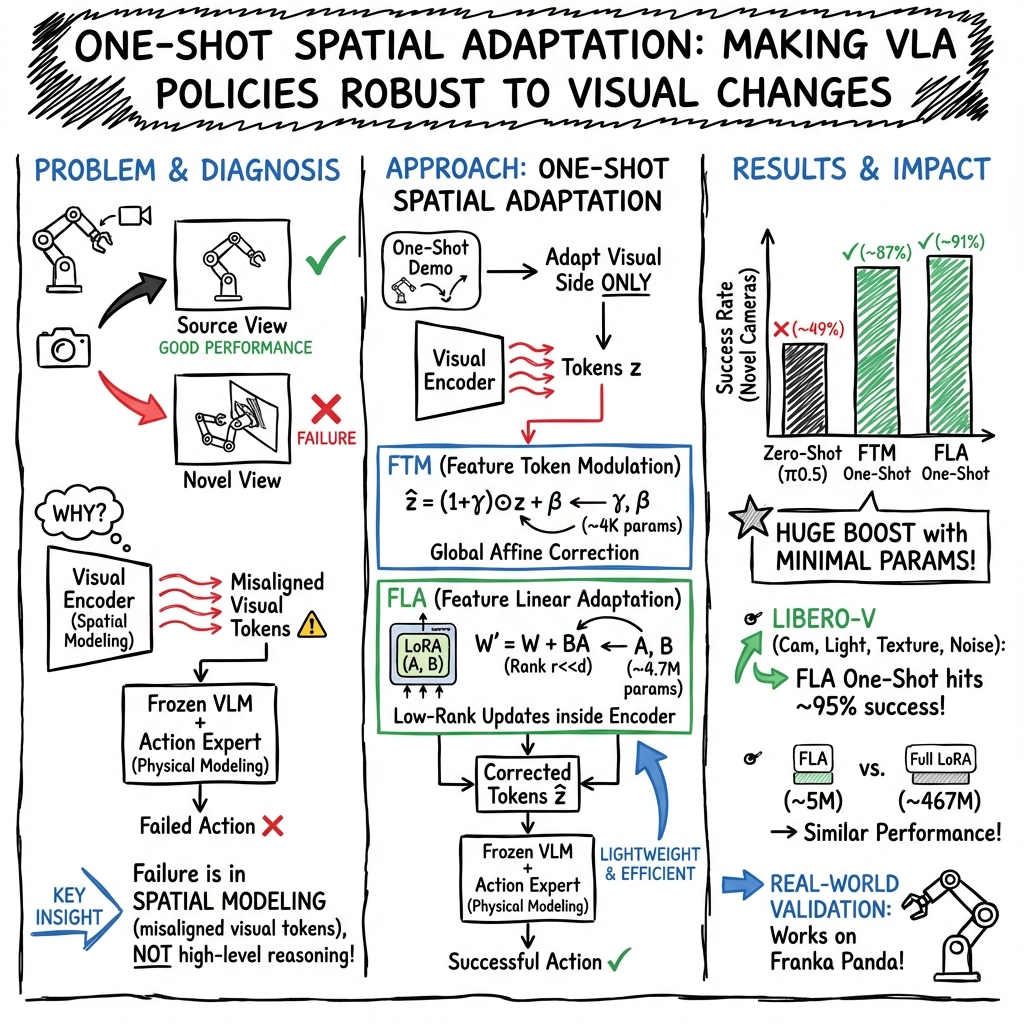

Abstract: Vision-language-action (VLA) models achieve strong in-distribution performance but degrade sharply under novel camera viewpoints and visual perturbations. We show that this brittleness primarily arises from misalignment in Spatial Modeling, rather than Physical Modeling. To address this, we propose a one-shot adaptation framework that recalibrates visual representations through lightweight, learnable updates. Our first method, Feature Token Modulation (FTM), applies a global affine transformation to visual tokens and improves Libero viewpoint accuracy from 48.5% to 87.1% with only 4K parameters. Building on this, Feature Linear Adaptation (FLA) introduces low-rank updates to the ViT encoder, achieving 90.8% success with 4.7M parameters -- matching LoRA-scale finetuning at far lower cost. Together, these results reveal substantial untapped robustness in pretrained VLA models and demonstrate that targeted, minimal visual adaptation is sufficient to restore viewpoint generalization.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching robot “brains” (called vision–language–action or VLA models) to keep working when the camera view changes. Today, many robots do great when the camera is placed just right, but if you move the camera to a new angle or change the lighting, they get confused and fail. The authors show that most of this failure isn’t because the robot can’t think or act—it’s because the “seeing” part (the visual features) becomes misaligned. They then show two tiny, fast fixes that adjust the visual features so the robot works well again, even from new viewpoints.

What questions did the paper ask?

- Why do VLA models break when the camera angle or lighting changes? Is it the vision part, the reasoning part, or the action part?

- Can we fix this quickly without retraining the whole model or collecting tons of new data?

- How little change is needed to make the robot robust again?

How did they try to solve it?

Think of a VLA model as two main parts working together:

- Spatial Modeling (the “eyes”): the vision encoder that figures out where things are in the picture—positions, angles, and which object is where.

- Physical Modeling (the “brain and hands”): the reasoning and action parts that choose what the robot should do next.

The authors’ idea: when the camera view changes, the “eyes” send slightly “warped” information to the brain. The brain and hands are fine, but they’re getting fuzzy directions. So, fix the “eyes” with a small tune-up.

Two quick-fix methods

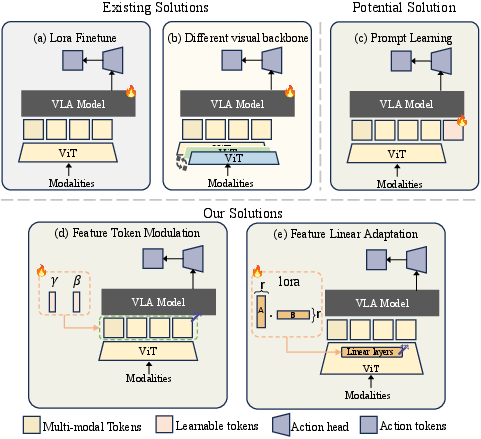

- Feature Token Modulation (FTM)

- What it does: it gently rescales and recenters the visual features before they go into the rest of the model.

- Analogy: like adjusting brightness and contrast on a photo so it looks “normal” again.

- How big is it? Tiny—about 4,000 trainable numbers.

- Why it helps: if the camera view shifts, some visual measurements become off. FTM shifts them back into place.

- Feature Linear Adaptation (FLA)

- What it does: adds small, low-rank “knobs” inside the vision encoder (a Vision Transformer) to better align features with the new view.

- Analogy: instead of replacing the whole lens, you add a few adjustable dials to correct the image.

- How big is it? Small—about 4.7 million trainable numbers (far less than full finetuning, which can be ~467 million).

- Why it helps: it slightly adjusts how the vision encoder processes images, making features line up correctly again.

What “one-shot adaptation” means: they adapt the model to the new camera or visuals using just a single demonstration per task—very fast and with very few parameters.

How they tested it

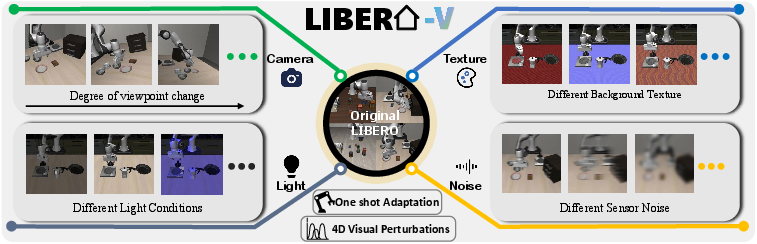

They built a benchmark called Libero-V that tests robots under:

- new camera viewpoints,

- different lighting,

- different background textures,

- visual noise.

They compared their tiny fixes (FTM and FLA) to bigger, heavier methods like LoRA finetuning (which updates hundreds of millions of parameters) and to other systems that use special geometry-aware visual backbones.

What did they find?

Here are the key takeaways:

- The main problem is in Spatial Modeling (the vision part), not in the robot’s reasoning or action modules. In other words, the “brain and hands” are fine—the “eyes” need a small adjustment.

- Tiny fixes work surprisingly well:

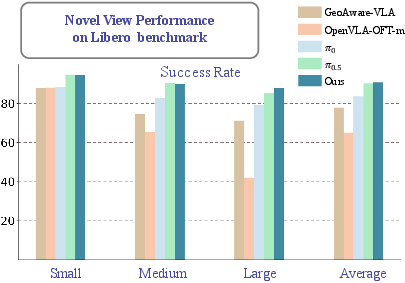

- With FTM (only ~4K parameters), success on new camera viewpoints jumped from about 48.5% to 87.1%.

- With FLA (~4.7M parameters), success reached about 90.8%, matching the performance of heavy LoRA finetuning (~467M parameters) but with around 99× fewer trainable parameters.

- Robust across other visual changes too: On the broader Libero-V tests (camera, lighting, texture, noise), FLA averaged about 94.8% success—again, close to or better than heavy finetuning, but much more efficient.

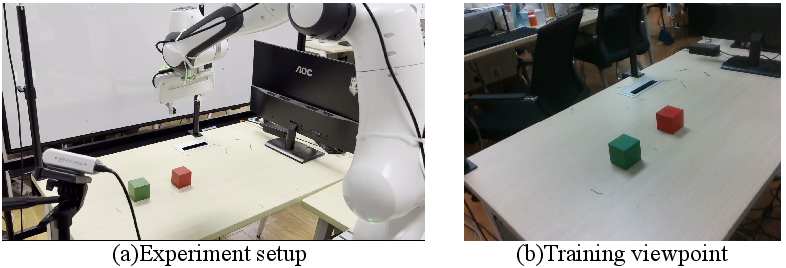

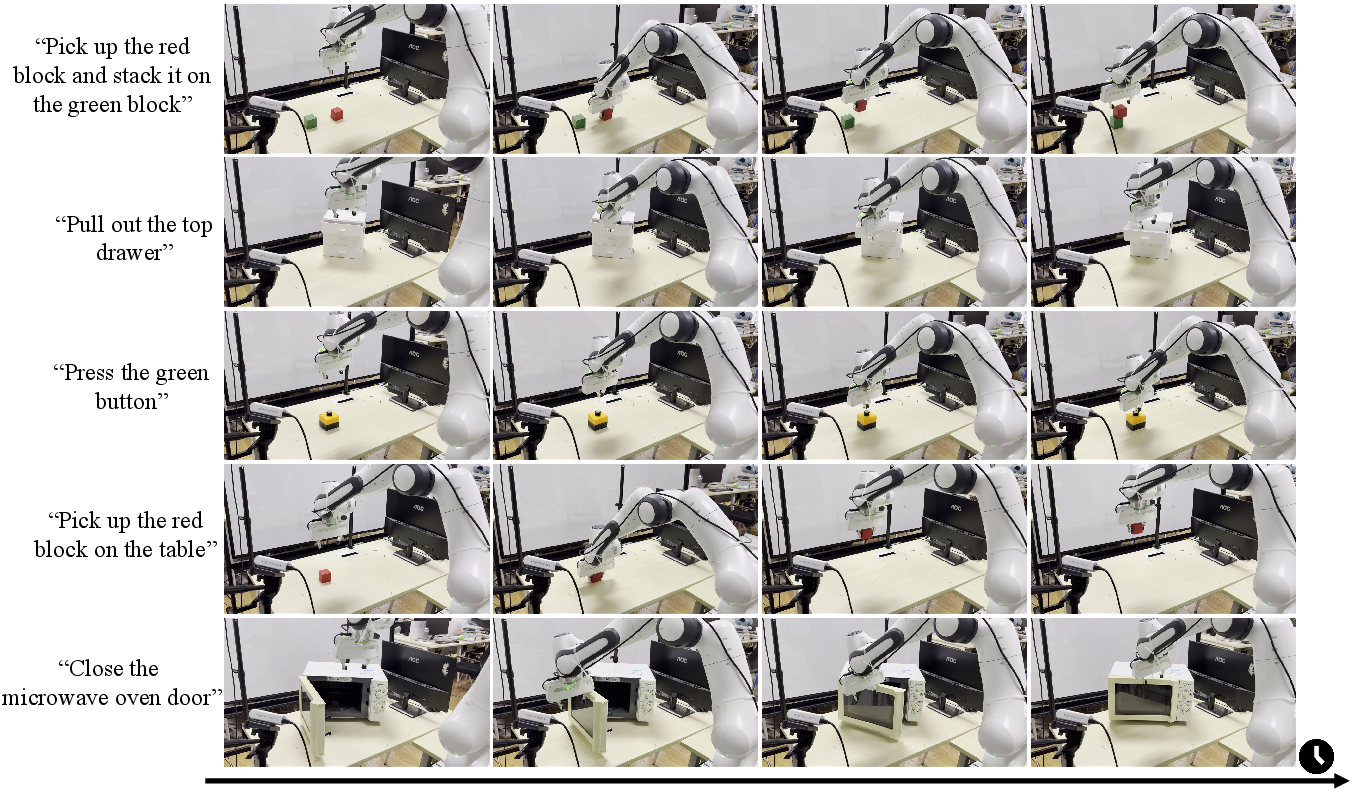

- Real robot tests: With just one demonstration from a new camera angle, the adapted policy successfully completed several real-world tasks (like stacking blocks or closing a microwave door).

Why this is important: it shows there’s “hidden” robustness already inside pretrained VLA models. You don’t need to retrain everything or collect lots more data—small, targeted tweaks to the vision features can unlock strong generalization.

Why does it matter?

- Faster, cheaper adaptation: Robots can be deployed in new places (homes, offices, factories) where camera angles and lighting vary, without expensive retraining.

- Simpler pipelines: Instead of building complex 3D or geometry-heavy models or collecting massive multi-view datasets, you can do minimal adaptation and still get strong results.

- Practical reliability: Robots become more dependable in everyday, messy environments—exactly where we need them most.

In short, the paper’s message is encouraging: robots already have good “brains.” Give their “eyes” a small tune-up when the view changes, and they’ll perform well again.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a consolidated list of knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that remain unresolved by the paper. Each point is framed to be concrete and actionable for future research.

- Causal evidence for “Spatial vs Physical Modeling” misalignment: The claim that viewpoint brittleness primarily arises from spatial embeddings (not physical reasoning) is supported by performance gains but lacks direct measurements (e.g., embedding drift metrics, targeted interventions that perturb only physical modules, or causal ablation studies).

- Generality across base architectures: FTM/FLA are evaluated only on π0 and π0.5; it remains unknown whether the same gains hold for other VLA families (e.g., RT-2, Octo, OpenVLA) and alternative visual backbones beyond SigLIP.

- Cross-robot and cross-embodiment transfer: The approach is validated on a single robot (Franka) and a limited real-world setup; generalization to different manipulators, kinematics, gripper types, and camera placements is not assessed.

- Domain-level vs task-level adaptation: One-shot adaptation uses a single demonstration per task; it is unclear whether a single domain-level adaptation (learned on one/few tasks) transfers across many tasks within the same domain.

- Sample complexity and data requirements: The paper does not quantify how performance scales with the number of demonstrations (1 vs 2–10) or the diversity of adaptation data (multiple viewpoints, varied scenes), nor whether unlabeled or self-supervised adaptation could suffice.

- Stability and catastrophic forgetting: Post-adaptation performance on the original (in-distribution) viewpoint/domain is not reported; potential trade-offs (forgetting, negative transfer) remain unquantified.

- Continual and online adaptation: The method is offline and one-shot; robustness under gradual viewpoint drift, frequent camera reconfigurations, or streaming test-time adaptation (with/without labels) is unexplored.

- Robustness to broader visual shifts: Evaluation covers viewpoint, lighting, texture, and noise, but omits other realistic factors (occlusions/clutter, dynamic distractors, motion blur, reflective/transparent surfaces, camera intrinsics changes, lens distortion, resolution/cropping, color cast, compression artifacts).

- Combined perturbations: Performance under simultaneous multi-factor shifts (e.g., viewpoint + lighting + noise) is not reported; compounding effects and interaction robustness remain unknown.

- Long-horizon and compositional tasks: Gains on “Long” suites are smaller; it is unclear whether spatial adaptation alone suffices for tasks requiring complex planning, memory, or compositional multi-step reasoning.

- Layer-wise adaptation design: FLA adapts linear layers in the ViT, but there is no paper of which layers (early, middle, late), patch embeddings, or attention blocks are most impactful; rank/placement search could yield better robustness with fewer parameters.

- Dynamic/conditional modulation: FTM uses global, input-agnostic γ/β; whether observation-conditioned or token-/region-specific modulation (e.g., spatially varying FiLM) yields better invariance is an open question.

- Combining adaptation strategies: The paper evaluates FTM and FLA independently; potential synergies (e.g., stacked FTM+FLA, prompts plus FLA, adapters plus FTM) are not explored.

- Fairness of baseline comparisons: LoRA comparisons report very large trainable parameter counts; a matched-parameter or matched-compute comparison (e.g., low-rank per-layer budgets, wall-clock, GPU-hours) is missing, creating uncertainty about efficiency claims.

- Multi-view dependence: Results rely on two cameras (wrist + third-person); robustness with a single camera, camera dropout/failure, or changing the number and arrangement of views is not evaluated.

- Cross-category and semantic shifts: The assumption that task semantics remain unchanged under viewpoint shifts is not tested against new object categories, varied morphologies, or visually novel semantics that may require changes in physical reasoning.

- Real-world validation scale: Real-world results are qualitative and limited to five tasks; no quantitative success rates, repeated trials, safety metrics, or failure analyses are provided.

- Benchmark reproducibility and coverage: Libero-V construction details (perturbation generators, seeds, calibration settings, release status) are sparse; standardized protocols for severity scaling and dataset release would improve reproducibility.

- Adaptation scheduling and selection: Strategies for when to adapt, how to select the adaptation demonstration (viewpoint, scene), and how to manage multiple domain-specific adapters (routing, gating) across environments remain open.

- Effects on language grounding: The language encoder is frozen; the impact of visual adaptation on language-vision alignment (especially under noisy/ambiguous instructions or multilingual inputs) is unmeasured.

- Mechanistic understanding of “latent robustness”: Claims of latent invariance are not accompanied by analyses (e.g., attention maps, representation similarity, geometry sensitivity) that explain why simple affine/low-rank corrections are effective.

- Safety, reliability, and deployment: Adaptation-induced behaviors under edge cases (near collisions, occlusions during manipulation) and the need for guardrails or uncertainty estimation are not addressed.

- Metrics beyond success rate: The paper focuses on SR; effects on path efficiency, time-to-success, manipulation precision, energy usage, and recovery from errors are not evaluated.

- Scalability to many tasks/domains: Managing and storing per-task/domain adapters, switching policies, and memory footprints for large task libraries is not discussed; a scalable multi-domain adaptation framework is needed.

Glossary

- Action expert: A specialized module that helps generate actions from multimodal inputs in a VLA policy. "After adaptation, all multimodal tokens are processed by the pretrained VLM and action expert to generate the final policy."

- Action tokens: Discrete symbols representing robot control commands produced step-by-step by the policy. "The policy operates on language and visual observations and autoregressively produces discrete action tokens at each control timestep."

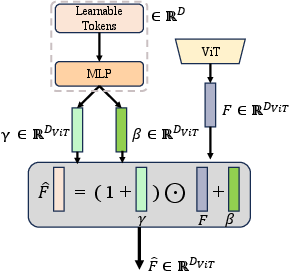

- Affine transformation: A linear scaling and shifting operation applied to features to correct distribution shifts. "Feature Token Modulation (FTM), applies a global affine transformation to visual token embeddings using only two learnable parameter vectors (γ, β)."

- Autoregressively: A sequential generation process where each output depends on previous outputs. "a multimodal transformer decoder g(·) with separate expert weight that autoregressively predicts action tokens conditioned on the fused embeddings."

- BitFit: A parameter-efficient finetuning method that updates only bias terms of a model. "Representative approaches include adapters, LoRA, Prefix-Tuning, and BitFit, all of which introduce small learnable modules while keeping the majority of the backbone frozen."

- Domain randomization: A data-centric strategy that increases visual diversity during training to improve robustness. "improve viewpoint invariance by increasing visual diversity through domain randomization, multi-view demonstrations, or large-scale visual perturbation datasets"

- Distribution shifts: Changes in input data distribution that can degrade model performance. "providing a unified framework for assessing robustness under diverse distribution shifts."

- Embedding space: The feature space where encoded inputs (e.g., images) are represented and compared. "viewpoint shifts can induce significant drifts in the embedding space of pretrained ViT encoders"

- Embodied intelligence: AI systems that perceive and act in the physical world, often via robots. "Recent advances in vision-language-action (VLA) models have significantly advanced the field of embodied intelligence."

- Feature Linear Adaptation (FLA): A lightweight adaptation applying low-rank updates inside the visual encoder to realign features. "Feature Linear Adaptation (FLA) introduces low-rank updates to the ViT encoder, achieving 90.8% success with 4.7M parameters—matching LoRA-scale finetuning at far lower cost."

- Feature Token Modulation (FTM): A minimal adaptation that globally scales and shifts visual token embeddings to restore alignment. "Feature Token Modulation (FTM), applies a global affine transformation to visual token embeddings using only two learnable parameter vectors (γ, β)."

- Franka Emika robot: A robotic manipulator used for real-world validation of manipulation tasks. "we deployed the policy on a Franka Emika robot."

- GELLO framework: A system used to collect human demonstrations for adaptation. "We collected a single human demonstration from a novel viewpoint using the GELLO framework and applied one-shot FLA adaptation."

- GeoAware-VLA: A VLA variant that uses a geometry-aware visual backbone and trains policies from scratch. "GeoAware-VLA replaces its visual backbone with VGGT and trains policies from scratch"

- Geometric consistency: A representation-centric principle that enforces 3D-consistent features across views. "representation-centric robustness by enforcing geometric consistency"

- Latent robustness: Inherent but unexpressed robustness that can be activated with minimal adaptation. "pretrained VLA models inherently encode latent robustness, which can be efficiently activated through minimal adaptation"

- Libero-Plus: A large-scale multi-view dataset used to improve robustness and evaluate VLA models. "Libero-Plus introduces four controlled perturbation types—camera viewpoint, lighting, background texture, and visual noise"

- Libero-V (Visual) benchmark: An evaluation suite integrating viewpoint and visual perturbations for systematic robustness testing. "we construct the Libero-V (Visual) benchmark, which integrates varying levels of viewpoint and visual perturbations from Libero-Plus"

- LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation, a parameter-efficient finetuning method that adds trainable low-rank updates to weight matrices. "A common solution is to perform full or parameter-efficient fine-tuning of the VLA backbone θ, such as LoRA-based updates"

- Low-rank decomposition: Factorizing weight updates into low-dimensional matrices to reduce parameter count. "LoRA introduces a low-rank decomposition,"

- Meta-learning: A paradigm where models learn to adapt quickly to new tasks or domains. "Inspired by the principles of meta-learning, we believe that robust behavior can be generated through effective adaptation rather than extensive retraining."

- Multimodal transformer decoder: A sequence model that fuses visual and language embeddings to generate actions. "a multimodal transformer decoder g(·) with separate expert weight that autoregressively predicts action tokens conditioned on the fused embeddings."

- One-shot adaptation: Adapting a model to a new domain using a single demonstration or minimal data. "we propose a one-shot adaptation framework that recalibrates visual representations through lightweight, learnable updates."

- Out-of-distribution: Data that differs significantly from the training distribution, often causing performance drops. "fail to generalize to out-of-distribution scenarios"

- Parameter-efficient finetuning (PEFT): Techniques that adapt models with minimal trainable parameters, keeping most weights frozen. "Parameter-efficient finetuning(PEFT) has emerged as an effective alternative to full-model adaptation, enabling models to specialize to new tasks or domains with minimal trainable parameters."

- Physical Modeling: The VLA component that integrates language, spatial features, and action history to plan and execute actions. "We show that this brittleness primarily arises from misalignment in Spatial Modeling, rather than Physical Modeling."

- Prompt-based adaptation: Adding learnable tokens to model inputs to condition behavior on new contexts. "Prompt-based adaptation introduces learnable tokens concatenated directly to multi-modal embeddings"

- Proprioceptive states: Internal sensor readings (e.g., joint positions) describing the robot’s body state. "integrate varied visual inputs, language instructions, and proprioceptive states, along with noisy actions, to generate a shared action policy"

- SigLIP visual backbone: A specific visual encoder architecture used within the VLA. "we fine-tune only the linear layers within the SigLIP visual backbone of π_{0.5}"

- Spatial Modeling: The visual encoding component that captures spatial relations like positions and occlusions from images. "We show that this brittleness primarily arises from misalignment in Spatial Modeling, rather than Physical Modeling."

- ViT encoder: A Vision Transformer module that encodes images into token embeddings. "Feature Linear Adaptation (FLA) introduces low-rank updates to the ViT encoder"

- Vision-language-action (VLA) models: Policies that unify perception, language understanding, and action generation. "Vision-language-action (VLA) models achieve strong in-distribution performance but degrade sharply under novel camera viewpoints and visual perturbations."

- Visual perturbations: Changes in visual conditions (e.g., lighting, texture, noise) that challenge model robustness. "VLA models achieve strong in-distribution performance but degrade sharply under novel camera viewpoints and visual perturbations."

- Viewpoint invariance: The property of maintaining performance despite changes in camera perspective. "these methods improve viewpoint invariance."

- Viewpoint shift: A change in camera position or angle that alters spatial configuration in the scene. "A viewpoint shift primarily alters the spatial configuration of the observed scene"

- Visual grounding: Aligning language instructions with visual inputs to identify relevant objects and actions. "demonstrating the potential of language-conditioned visual grounding for general-purpose robots."

- Visual tokens: Discrete embedding units produced by the visual encoder to represent image features. "applies a global affine transformation to visual token embeddings using only two learnable parameter vectors (γ, β)."

Practical Applications

Practical Applications Derived from the Paper

The paper introduces two parameter-efficient, one-shot visual adaptation mechanisms—Feature Token Modulation (FTM) and Feature Linear Adaptation (FLA)—that restore viewpoint and visual perturbation robustness in pretrained vision-language-action (VLA) models. It also presents Libero-V, a benchmark that isolates robustness across camera, lighting, texture, and noise shifts. Below are actionable applications grouped by deployment horizon, with sector links, potential tools/workflows, and dependencies.

Immediate Applications

- Robotics (manufacturing, logistics): one-shot “camera/viewpoint calibration” for existing VLA-powered manipulators

- What: Deploy FTM (4K parameters) or FLA (4.7M parameters) to recover performance when cameras are repositioned, changed, or lighting/background varies.

- Tools/workflows: a “Calibration Wizard” that records a single demonstration per task, runs 2k adaptation steps, and deploys the adapter; an “Adapter Manager” that versions and swaps adapters after maintenance or relocation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: requires a pretrained VLA (e.g., Pi_0.5 with a ViT-like visual backbone such as SigLIP), access to the visual token stream or ViT layers, a single human demo per task, and basic GPU/edge compute for brief adaptation.

- Field service robots (facilities, hospitality): rapid on-device adaptation to lighting/texture changes

- What: Use FTM for “micro-adaptation” (global affine correction) at deployment sites to stabilize perception under variable lighting and surfaces.

- Tools/workflows: a lightweight “FTM micro-adapter” library embeddable on edge devices; a technician workflow capturing a brief demo and applying modulation parameters.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consistent task semantics; minimal changes to action dynamics; ability to freeze the policy and adapt vision only.

- Warehouse/fulfillment: robust picking under variable camera setups

- What: Apply FLA to adapt the ViT encoder when cameras are moved after maintenance or storage reconfiguration.

- Tools/workflows: “Auto-recover viewpoint invariance” routine integrated with maintenance tickets; post-change acceptance test using Libero-V camera subset.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stable action expert; moderate compute to train low-rank updates; optionally, dual cameras (wrist + third-person) as used in experiments.

- Home robotics (daily life): consumer-facing auto-calibration after relocation

- What: A guided smartphone app instructs the user to provide a single demonstration; the robot applies FTM/FLA and resumes reliable manipulation in a new room/viewpoint.

- Tools/workflows: “One-shot home recalibration” flow; adapter packaged as a small model patch (KB–MB) for over-the-air updates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: base model compatibility; safe demo recording; trivial compute for short adaptation.

- AR/VR and embodied agents (education, retail): fast visual-domain alignment for instruction-following agents

- What: Plug-in modulation of ViT tokens to handle changing décor/lighting in classrooms, retail floors, or demos without retraining.

- Tools/workflows: “Visual Token Modulation” plug-in for ViT-based pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: perception dominates failure modes (spatial misalignment) rather than action logic; ViT-like backbone.

- MLOps for embodied AI: parameter-efficient hotfixes and patching

- What: Ship small adapters instead of full model retrains to address site-specific domain shifts; rollback via versioned adapter registry.

- Tools/workflows: “Adapter Registry” and CI/CD hooks that run Libero-V subsets as acceptance tests; telemetry for drift detection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: standardized adapter interfaces to the visual encoder; monitoring for safe deployment.

- Robustness evaluation (academia/industry QA): Libero-V-based acceptance testing and procurement benchmarking

- What: Use Libero-V (camera, light, texture, noise) to validate robustness claims of VLA systems before purchase or deployment.

- Tools/workflows: “Libero-V compliance suite” with pass/fail thresholds; test harness integrated into evaluation pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: availability of Libero-V tasks or equivalents; controlled perturbation protocols.

- Research tool (academia): probing spatial vs. physical modeling failures

- What: Use FTM as a diagnostic to test whether failures stem from spatial embeddings; escalate to FLA if deeper features need realignment.

- Tools/workflows: “Spatial-vs-Physical Probe Kit” that applies token-level and low-rank updates to isolate bottlenecks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to visual encoder internals; frozen policy components for controlled experiments.

Long-Term Applications

- Fleet-scale auto-calibration (industrial robotics, logistics): centralized adapter generation and distribution

- What: A service that collects brief demos per site/task, trains adapters, and distributes signed patches fleet-wide.

- Tools/products: “AdapterOps” platform with multi-robot support; automated drift detection triggering re-adaptation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: standardized visual backbones across robots; secure patch pipelines; robust validation before rollout.

- Cross-platform adapter banks (vendor ecosystem): reusable adapters for common camera configurations

- What: Pretrained adapter libraries for typical viewpoint layouts (e.g., ceiling, shelf, mobile mount) to minimize per-site adaptation time.

- Tools/products: “Adapter Bank” marketplace; metadata linking adapters to camera geometry.

- Assumptions/dependencies: sufficient similarity between target and source domains; standardized adapter APIs.

- Continuous/online adaptation (autonomy): incremental FTM/FLA updates under drift

- What: On-the-fly correction to tokens or ViT layers as the environment evolves (e.g., seasonal lighting changes).

- Tools/workflows: online learning with safety gates; rollbacks on confidence drops; watchdogs monitoring success rates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: safe online learning infrastructure; robust detection of harmful updates; formal verification for critical tasks.

- Sector standards and regulation (policy): robustness certification requirements for embodied AI

- What: Introduce procurement standards mandating Libero-V-like robustness tests; publish minimum SR thresholds under defined shifts.

- Tools/workflows: “VLA Robustness Standard” documents; accredited test labs; reporting templates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus on benchmarks; sector-specific thresholds; alignment with safety guidelines.

- Healthcare robotics: OR-ready perception adaptation for surgical assist robots

- What: One-shot calibration to variable OR lighting, camera repositioning, instrument textures; maintain high reliability without retraining.

- Tools/workflows: FDA-aligned validation protocols; locked action policies with only vision-side adapters; conservative update gating.

- Assumptions/dependencies: rigorous clinical validation; fail-safe adaptation; domain-specific robustness criteria; strong logs and audit trails.

- Autonomous driving and drones: extending token/encoder adaptation to fast-changing domains

- What: Investigate whether FTM/FLA-style visual adaptation stabilizes perception stacks under weather, sensor aging, or camera remounts.

- Tools/workflows: “Vision Adapter SDK” integrated into perception modules; simulation-in-the-loop validation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: adaptation latency must meet real-time constraints; policy interplay with temporal dynamics; broader multimodal fusion considerations.

- Energy and infrastructure inspection robots: robust perception in harsh conditions

- What: Apply adapters to handle glare, texture variations (rust, corrosion), and camera mount changes in plants or offshore sites.

- Tools/workflows: inspector demo collection; periodic recalibration schedule; Libero-V-inspired site-specific tests.

- Assumptions/dependencies: task semantics stable; ruggedized compute; safety case for continual updates.

- Education and training: curricula and kits for robustness-aware embodied AI

- What: University labs and bootcamps use FTM/FLA and Libero-V to teach domain adaptation, robustness measurement, and parameter-efficient finetuning.

- Tools/workflows: teaching modules; open-source adapter libraries; reproducible benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: accessible hardware (e.g., low-cost arms); curated tasks aligned with Libero suites.

- Software productization (CV ecosystems): general-purpose visual adapter libraries for ViT-based applications

- What: Offer an SDK implementing token modulation and low-rank encoder updates for surveillance analytics, retail analytics, and industrial CV.

- Tools/products: “Visual Adapter SDK” with APIs for gamma/beta modulation and low-rank layer patches; profiling tools for parameter-efficiency.

- Assumptions/dependencies: tasks dominated by spatial representation shifts; minimal changes to downstream reasoning modules.

- Multimodal foundation models: generalized robustness adapters beyond vision

- What: Extend the “adapter-on-perception” principle to audio, haptics, or radar, minimizing full-stack retraining under domain shifts.

- Tools/workflows: multimodal adapter design patterns; cross-modal benchmarks analogous to Libero-V.

- Assumptions/dependencies: viability of affine/low-rank updates for non-visual encoders; new metrics and safety checks per modality.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.