Lectures on Quantum Field Theory on a Quantum Computer (2512.02706v1)

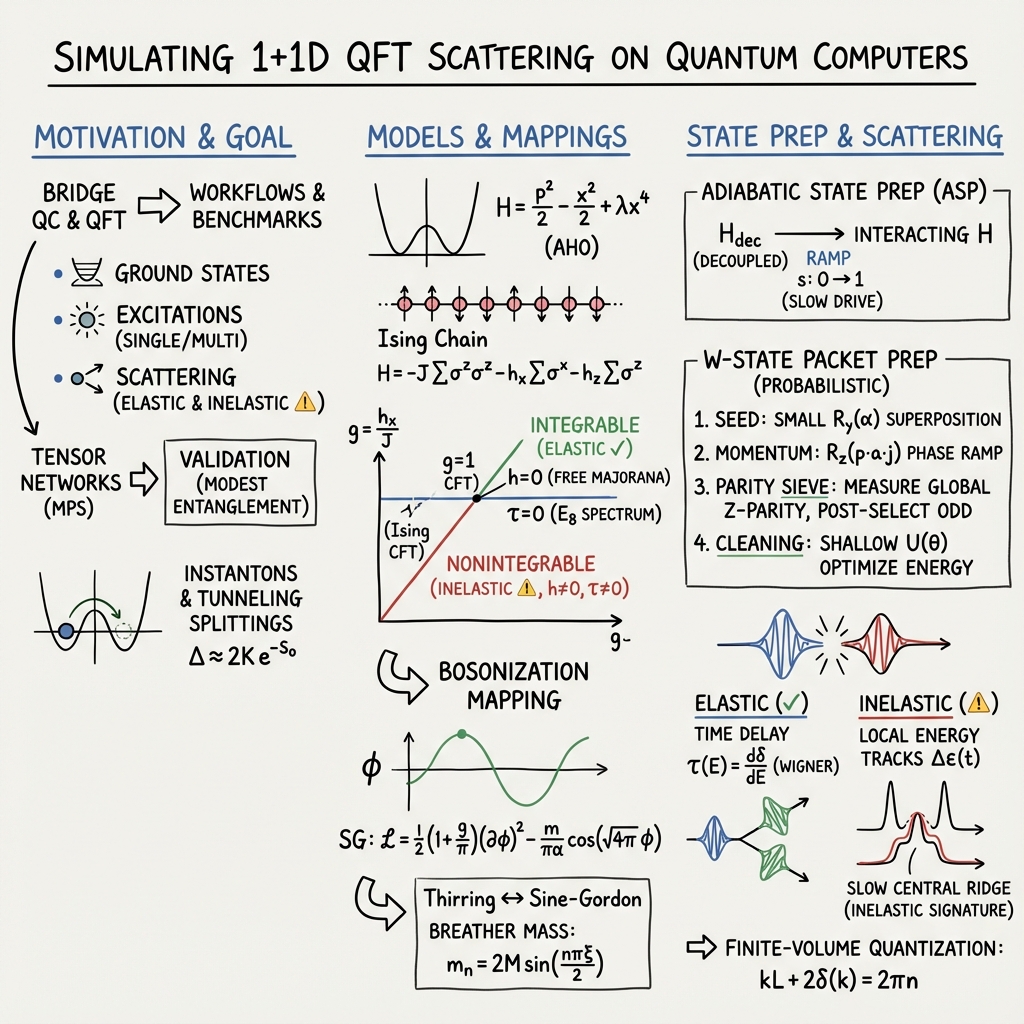

Abstract: The lecture notes cover the basics of quantum computing methods for quantum field theory applications. No detailed knowledge of either quantum computing or quantum field theory is assumed and we have attempted to keep the material at a pedagogical level. We review the anharmonic oscillator, using which we develop a hands-on treatment of certain interesting QFTs in $1+1D$: $φ4$ theory, Ising field theory, and the Schwinger model. We review quantum computing essentials as well as tensor network techniques. The latter form an essential part for quantum computing benchmarking. Some error modelling on QISKIT is also done in the hope of anticipating runs on NISQ devices. These lecture notes are the expanded version of a one semester course taught by AS during August-November 2025 at the Indian Institute of Science and TA-ed by UB. The programs written for this course are available in a GitHub repository.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

This is a set of friendly lecture notes that show how to use quantum computers to paper quantum field theory (QFT) — the math that describes tiny particles and their interactions. Instead of assuming you already know a lot, the authors start from simple, familiar ideas (like masses on springs) and build up to small but real field theories. Along the way, they teach both quantum computing basics and powerful classical tools you can use to check your work. They also share code so you can try things yourself.

What the authors wanted to do

In simple terms, the authors set out to:

- Teach the basics you need from physics and quantum computing to simulate simple quantum fields.

- Start with easy, hands-on models (like a slightly “stiffer” spring or a “double valley” potential) and connect them to real mini-field theories in 1+1 dimensions.

- Show how to find the ground state (the lowest-energy state), build excited states, and “smash” them together to paper scattering and particle production.

- Compare quantum-computer methods with smart classical methods (called tensor networks) so you can tell if your quantum results make sense.

- Prepare you for running on today’s imperfect devices by modeling errors in software before touching real hardware.

How they approached it (with everyday analogies)

To keep things concrete, the authors follow this path:

1) Start with a single “atom-sized tethered to a spring,” then make it non‑linear

- Harmonic oscillator: like a mass on a perfect spring (evenly spaced energy “steps”).

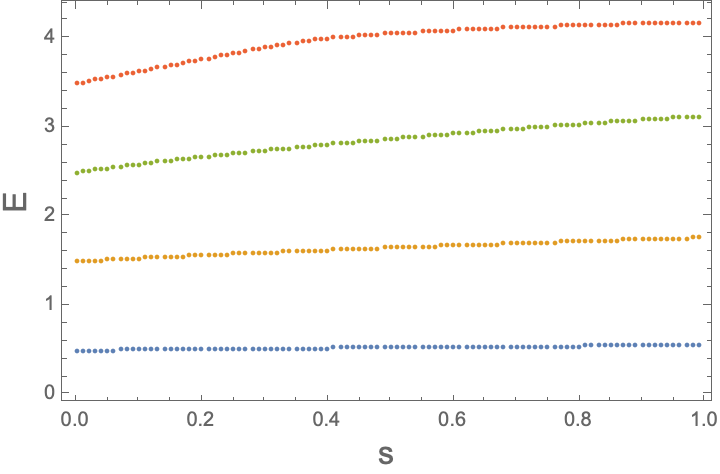

- Anharmonic oscillator: add a little extra stiffness so the spring gets harder to stretch at large moves. This changes the spacing between energy levels — they spread out as energy increases.

- Double well: imagine a track with two equal valleys and a hill in between. A quantum particle can “tunnel” through the hill, even if it doesn’t have the classical energy to climb it. This tunneling splits what would be a single energy level into two very close ones.

Analogy: Think of marbles rolling in bowls. In a double bowl (two valleys), the marble mostly stays in one side, but in quantum mechanics it can “ghost” into the other side. That “ghosting” causes a tiny energy difference that you can actually calculate.

2) Build up to fields by connecting many oscillators

- Put many of these oscillators in a line and add springs between neighbors. In the continuous limit, this becomes a simple field theory called ϕ⁴ theory.

- If you focus only on the two lowest energy states in each site of a double-well chain, you get a field theory closely related to the Ising model (famous in magnetism).

- Replace the quartic potential with a “cosine-shaped” one (think of a wavy, rippling floor). That connects to the Schwinger and Thirring models, which also show up in particle physics.

3) Use quantum algorithms as tools

- Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT, not to be confused with quantum field theory): like turning a sound wave into notes, it helps change perspective to see patterns more clearly.

- Quantum Phase Estimation: a quantum stopwatch for measuring energies of states.

- Hadamard test and LCU (Linear Combination of Unitaries): tricks to measure properties and build specific operations.

- Adiabatic state preparation (including W‑states): gently “morphs” easy states into harder, target states without shaking them too much.

4) Check with classical “quantum-inspired” methods

- Tensor Networks (especially Matrix Product States, or MPS): smart ways to compress quantum states when entanglement isn’t huge. Algorithms like TEBD, DMRG, and TDVP let you find ground states, simulate time evolution, and paper excitations efficiently.

- Why this matters: on near-term quantum hardware, noise is a problem. Classical tensor networks help you verify that your quantum circuits are producing believable results.

5) Anticipate real-hardware limits

- They simulate noise using Qiskit to predict how today’s “noisy” devices might behave, without relying on actual hardware runs.

What they found (and why it matters)

This is a teaching-first paper, so the “results” are mostly clear demonstrations and benchmark targets rather than brand-new physics discoveries. The key takeaways are:

- Energy levels change in predictable ways when you make a spring “harder” (the anharmonic oscillator). The gaps between levels get bigger as you go up in energy. That’s useful for designing qubit-like systems in the lab and understanding how real devices differ from ideal ones.

- In the double-well, the two lowest energy levels are almost the same but split due to tunneling. The authors show how to estimate this “tunneling splitting” using a semiclassical idea called an instanton (imagine the particle taking a sneaky path under the hill). They provide numerical values and simple formulas you can test on your own code.

- They connect these simple models to small field theories in 1+1 dimensions:

- ϕ⁴ theory (a basic interacting scalar field),

- Ising field theory (linked to magnetism and phase transitions),

- Schwinger and Thirring models (important toy models for interactions and confinement).

- They outline practical quantum-computing pipelines for:

- Preparing ground states and excitations,

- Measuring energies,

- Simulating scattering and checking if new particles get produced.

- They show how tensor networks can benchmark quantum results when entanglement is not too large, which is vital for making sure quantum hardware or simulators are doing the right thing.

- They share code (Python, Qiskit, Julia with MPSKit/TensorKit, and optional Mathematica) so students can try everything hands-on.

Why this matters: Careful, simple benchmarks are the stepping stones to tackling much harder problems in physics. By making the bridge between toy models and real field theories, and between classical simulations and quantum circuits, the authors give learners a solid path to meaningful experiments.

What this might lead to

- A learning toolkit: Students and beginners get a practical, tested way to learn quantum field theory on quantum computers, with code and clear examples.

- Better benchmarks: The proposed test cases — like the tunneling splitting in the double well or spectra in ϕ⁴ theory — give the community common “targets” to check algorithms and devices.

- Faster progress on real problems: As quantum hardware improves, these methods could scale to field theories that are too hard for classical computers, helping us paper scattering, particle production, and even ideas related to quantum gravity.

- Cross-pollination: Mixing field theory, quantum computing, and tensor networks often leads to new techniques and insights, just as earlier generations discovered the renormalization group by thinking cleverly about computation.

In short: The notes are a friendly map for exploring quantum fields with quantum computers. They start simple, build intuition, teach both quantum and classical tools, and offer code and benchmarks so you can test, learn, and push further.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following points summarize what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper and suggest concrete directions future researchers could pursue:

- No validation on real quantum hardware: all results are from simulators or classical codes. Execute the proposed pipelines (ground-state preparation, spectroscopy, real-time scattering) on current IBMQ or other NISQ devices and report hardware-specific performance, stability, and reproducibility.

- Missing resource estimates for target QFT tasks: provide explicit qubit counts, gate-depth, and sampling complexity for theory, Ising field theory, and the Schwinger/Thirring models as functions of lattice size, local Hilbert space truncation, target precision, and evolution time.

- Encoding choices for bosonic fields are unspecified: detail the site-local encoding (binary, unary, compact boson truncation, GKP-like encodings), truncation levels per site, and their impact on norm bounds, simulation error, and circuit complexity.

- Hamiltonian simulation method selection is not made concrete: benchmark Trotterization, LCU/qubitization, and truncated Taylor approaches for these models, including error bounds and empirical constants, and identify the best approach per task (ground state, spectroscopy, scattering).

- Lack of a systematic noise paper: beyond basic Qiskit error modeling, quantify the effect of coherent errors, crosstalk, SPAM, drift, and calibration cycles; evaluate error mitigation strategies (zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation, measurement mitigation, randomized compiling) on end-to-end tasks.

- No finite-volume and boundary-condition analysis: quantify finite-volume artifacts in spectra and scattering, use Lüscher-like formulas to extract infinite-volume observables, and propose circuits/measurement strategies that minimize or correct for boundary effects.

- Continuum-limit and renormalization workflow not specified: define counterterm schemes on the lattice, give renormalized mass/coupling extraction procedures, and demonstrate continuum extrapolations for and sine-Gordon-type models within a quantum/classical hybrid workflow.

- Instanton physics only at leading order: compute the fluctuation determinant prefactor for the quartic double well explicitly, include multi-instanton and loop corrections, map the range of where DIGA is quantitatively reliable, and compare to high-precision numerics across the full parameter range.

- Absent high-order perturbative/resurgent analysis: generate Bender–Wu high-order coefficients for the anharmonic oscillator, perform Borel resummation and resurgence matching to instanton sectors, and compare to nonperturbative numerical results to quantify asymptotic accuracy.

- Ground-state preparation schedules lack performance guarantees: analyze spectral gaps and path-dependent diabatic errors for the adiabatic/W-state approaches; design and test schedules (e.g., local adiabatic, shortcuts-to-adiabaticity) with provable error bounds and practical resource costs.

- No comparison among state-preparation methods: empirically compare adiabatic, QPE-based, variational (VQE) and imaginary-time (QITE) preparation for the considered models, including robustness to noise and scaling with target precision.

- Real-time scattering in field theory remains algorithmically unspecified: construct scattering states on interacting backgrounds, design measurement protocols for phases and inelastic production (e.g., via number operators, wave-packet methods, Keldysh circuits), and validate against classical TN benchmarks.

- S-matrix extraction methodology is missing: develop finite-volume strategies (phase shifts via energy levels, Lüscher quantization conditions) and/or direct phase-estimation-based approaches to obtain S-matrix elements on a QC, including error analyses and resource counts.

- Particle production observables are not operationalized: define concrete measurement circuits for particle-number distributions, total/inclusive cross sections, and inelasticity, and quantify sampling requirements and detection fidelity.

- Gauge-invariant encoding for Schwinger/Thirring models is not detailed: specify Gauss-law constraints, link-variable encodings, or bosonization mappings used; analyze their qubit overhead and effects on circuit complexity and errors.

- Absence of “quantum advantage” regimes relative to MPS: identify parameter regions where entanglement growth makes MPS/TEBD/TDVP unreliable; design QC tasks that remain tractable and show advantage; provide cross-validation metrics.

- MPS benchmarking lacks error/systematics reporting: report bond-dimension scaling, truncation errors, convergence diagnostics, and comparison across libraries (MPSKit/TensorKit vs TeNPy) to ensure reproducibility and uncover failure modes.

- Spectroscopy pipelines need quantitative performance metrics: define spectral fidelity, line-position/width errors, and phase-estimation precision targets; relate these to circuit depth and shot counts, and validate on the anharmonic and double-well benchmarks.

- Wigner time delay only sketched: extend derivations to resonant tunneling and multi-barrier structures; design quantum circuits to measure scattering phases/time delays (e.g., interferometric phase estimation) and validate on solvable potentials.

- Discretization and truncation errors for bosonic fields are unquantified: analyze aliasing and cutoff effects from finite lattice spacing, finite momentum grids, and local Hilbert space truncation; propose error-control strategies and empirical calibration procedures.

- No comprehensive end-to-end reproducibility package: provide pinned environment versions, random seeds, datasets, and automated scripts to reproduce figures/tables across different machines; include performance profiles for varying hardware configurations.

- Extension beyond 1+1D left for future work: outline pathways and resource scaling for 2+1D and 3+1D and gauge theories, including encoding strategies, Hamiltonian simulation methods, and expected noise tolerances.

- Thermal and finite-density physics not addressed: propose algorithms for thermal state preparation (quantum Metropolis, minimally entangled typical states, thermofield double) and real-time dynamics at finite density; assess feasibility on NISQ hardware.

- Integration with multiscale/RG methods is missing: explore MERA or quantum RG-inspired circuits to perform coarse-graining and extract renormalized couplings directly on the QC; evaluate their practicality and accuracy.

- Hardware-aware compilation strategies are absent: test pulse-level optimization, dynamical decoupling, and layout-aware transpilation to reduce depth and noise for the proposed circuits; quantify gains and portability across devices.

Glossary

- Adiabatic state preparation: A method to prepare target quantum states by slowly varying a Hamiltonian so the system remains in its instantaneous eigenstate. "The recent technique of using W-state adiabatic state preparation will be reviewed in a pedagogical way."

- Anharmonic oscillator: A quantum oscillator with non-quadratic terms in the potential (e.g., quartic), leading to nonuniform level spacings and rich nonperturbative effects. "We review the anharmonic oscillator, using which we develop a hands-on treatment of certain interesting QFTs in $1+1D$: theory, Ising field theory, and the Schwinger model."

- Anti-instanton: The semiclassical tunneling solution corresponding to the reverse transition (opposite topological charge) of an instanton. "which corresponds to which is called the anti-instanton."

- Avoided crossing: A phenomenon where energy levels approach but repel each other due to coupling, producing a minimum gap that controls adiabatic transitions. "adiabatic ramps across avoided crossings in the doubleâwell can be compared to textbook LandauâZener and instanton expectations."

- Bender–Wu recursions: High-order perturbative recursion relations used to compute asymptotic series for the anharmonic oscillator. "eigenvalues and eigenvectors can be obtained essentially exactly using shooting methods, spectral techniques, or highâorder BenderâWu recursions."

- Borel resummation: A technique to assign finite values to divergent asymptotic series by transforming and resumming them in the Borel plane. "They generate ambiguities in the so-called Borel resummation of divergent series, which are cancelled by the perturbative sector in the framework of resurgence."

- Bosonized Schwinger and Thirring models: 1+1D fermionic gauge and four-fermion theories rewritten in equivalent bosonic field variables via bosonization. "The final physics chapter deals with the bosonized Schwinger and Thirring models."

- Collective coordinate: A parameter (e.g., an instanton’s center) reflecting a continuous symmetry of a classical solution that must be integrated over in semiclassical path integrals. "The parameter is a collective coordinate: translating the instanton does not change its action, and the path integral includes an integration over its position."

- Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG): A variational tensor-network algorithm for ground states of low-dimensional quantum systems with limited entanglement. "algorithms like TEBD (Time Evolving Block Decimation), DMRG (Density Matrix Renormalization Group) and Time-Dependent Variational Principle (TDVP)."

- Dilute instanton gas approximation (DIGA): An approximation treating instantons/anti-instantons as rare, well-separated events whose contributions add approximately. "This is the dilute instanton gas approximation (DIGA)."

- Euclidean path integral: The path-integral formulation in imaginary time, where tunneling solutions (instantons) dominate nonperturbative contributions. "The Euclidean path integral representation is"

- Fourier spectroscopy: Extracting energy spectra from time-evolution signals via Fourier transforms (e.g., on quantum devices). "phaseâestimation and Fourierâspectroscopy approaches can be checked against known line positions and widths;"

- Hadamard test: A circuit primitive to estimate real or imaginary parts of expectation values of unitary operators using an ancilla qubit. "the Hadamard test and Linear Combination of Unitaries (LCU)."

- Instanton: A finite-action Euclidean solution describing tunneling between classically separated minima, yielding exponentially small level splittings. "The instanton has a characteristic width in Euclidean time."

- Ising field theory: The continuum quantum field theory that arises from the scaling limit of the lattice Ising model. "The continuum limit of this theory is the Ising field theory."

- Landau–Zener: The two-level model predicting transition probabilities during passage through an avoided crossing under a time-dependent Hamiltonian. "adiabatic ramps across avoided crossings in the doubleâwell can be compared to textbook LandauâZener and instanton expectations."

- Linear Combination of Unitaries (LCU): A technique to implement operators expressed as weighted sums of unitaries, used in quantum algorithms for simulation. "the Hadamard test and Linear Combination of Unitaries (LCU)."

- Matrix Product States (MPS): A tensor-network ansatz efficiently representing low-entanglement 1D quantum states. "Tensor Network techniques like MPS (Matrix Product States) and algorithms like TEBD (Time Evolving Block Decimation), DMRG (Density Matrix Renormalization Group) and Time-Dependent Variational Principle (TDVP)."

- NISQ devices: Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum processors with limited qubit counts and significant noise, not yet fault-tolerant. "in the hope of anticipating runs on NISQ devices."

- One-loop determinant: The Gaussian fluctuation determinant around a classical saddle, providing the leading semiclassical prefactor. "Each contributes a factor , where is the one-loop determinant prefactor."

- Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT): The unitary implementing the discrete Fourier transform on quantum registers, central to many algorithms. "the quantum Fourier transform ( to distinguish from quantum field theory QFT)"

- Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE): An algorithm to estimate eigenphases (energies) of a unitary (Hamiltonian) given access to controlled time evolution. "quantum phase estimation (QPE)"

- Qiskit: An open-source quantum computing framework for building, simulating, and running quantum circuits. "Some error modeling on QISKIT is also done in the hope of anticipating runs on NISQ devices."

- Renormalization group (RG): A framework analyzing how physical systems change with scale, central to quantum field theory and critical phenomena. "Ken Wilson invented the renormalization group by thinking about quantum field theory on a classical computer."

- Resurgence: A program connecting perturbative and nonperturbative expansions via trans-series, resolving ambiguities in resummations. "which are cancelled by the perturbative sector in the framework of resurgence."

- Schwinger model: Quantum electrodynamics in 1+1 dimensions, exactly solvable and often used as a testbed for gauge theories. "Ising field theory, and the Schwinger model."

- Sine-Gordon models: Field theories with cosine potentials, supporting solitons and corresponding to bosonized versions of certain fermionic models. "the so-called Sine-Gordon models."

- Tangent-space methods: Techniques for analyzing excitations and dynamics around infinite MPS using variational tangent spaces. "For infinite MPS and tangent-space methods, we recommend Refs.~\cite{Vanderstraeten_2019,Haegeman_2013}."

- TDVP (Time-Dependent Variational Principle): A method projecting Schrödinger dynamics onto a variational manifold (e.g., MPS) to simulate time evolution. "algorithms like TEBD (Time Evolving Block Decimation), DMRG (Density Matrix Renormalization Group) and Time-Dependent Variational Principle (TDVP)."

- TEBD (Time Evolving Block Decimation): A tensor-network algorithm for simulating time evolution in 1D systems with short-range interactions. "algorithms like TEBD (Time Evolving Block Decimation), DMRG (Density Matrix Renormalization Group) and Time-Dependent Variational Principle (TDVP)."

- Tensor network: A class of structured representations for many-body states leveraging low entanglement to enable efficient computation. "Tensor Network techniques like MPS (Matrix Product States) and algorithms like TEBD (Time Evolving Block Decimation), DMRG (Density Matrix Renormalization Group) and Time-Dependent Variational Principle (TDVP)."

- Thirring model: A 1+1D exactly solvable fermionic field theory with current-current interactions, dual to the sine-Gordon model. "The final physics chapter deals with the bosonized Schwinger and Thirring models."

- Transfer matrix: A matrix relating wave amplitudes across layered regions, used to compute scattering through piecewise-constant potentials. "the total transfer matrix across the double--barrier structure is"

- Trans-series: Generalized asymptotic expansions combining perturbative series with exponentially small nonperturbative sectors. "A trans-series is a generalized asymptotic expansion that includes both perturbative and nonperturbative sectors, schematically"

- Wigner time delay: The energy derivative of the scattering phase, giving the delay experienced by a transmitted (or reflected) wavepacket. "the Wigner time delay for the transmission channel."

- WKB (Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin): A semiclassical approximation method for solving the Schrödinger equation in the short-wavelength limit. "the semi-classical WKB technique."

- W-state: An entangled state with a single excitation delocalized across many qubits, useful for certain state-preparation protocols. "The recent technique of using W-state adiabatic state preparation will be reviewed in a pedagogical way."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following items can be deployed now using the paper’s codebase, methods, and workflows, and are relevant across education, software, and quantum hardware prototyping.

- Education: lab-in-a-notebook course modules for quantum computing and QFT

- Sector: education

- What: Use the lecture notes plus the GitHub repository to build hands-on assignments covering the anharmonic oscillator, double-well instantons, 1+1D models (, Ising, Schwinger), and core quantum algorithms (QFT, QPE, Hadamard test, LCU; adiabatic W-state preparation).

- Tools/workflows: Python (Qiskit), Julia (MPSKit.jl, TensorKit.jl), TEBD/DMRG/TDVP scripts; reproducible notebooks with benchmark targets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Instructor familiarity with basic QM/QC; maintenance of the repository; hardware runs are simulated not physical.

- Quantum algorithm benchmarking on simulators

- Sector: software; quantum computing industry

- What: Validate ground-state preparation, phase estimation, and spectroscopy pipelines against known spectra and tunneling splittings of the anharmonic/double-well oscillator before moving to latticized field theories.

- Tools/workflows: Qiskit simulators with error models; comparison against exact diagonalization and semiclassical instanton predictions (e.g., ground-state splitting targets Δ≈0.3 at λ=0.1 and Δ≈1.28 at λ=0.7).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Noise models approximate real devices; scope limited to modest entanglement and 1+1D models.

- Hybrid classical–quantum benchmarking with tensor networks

- Sector: academia; software

- What: Use MPS-based TEBD/DMRG/TDVP calculations as a reference for quantum circuits simulating spectra, excitations, and scattering in 1+1D models.

- Tools/workflows: Julia MPSKit/TensorKit integrated with Python/Qiskit pipelines; automated cross-checks and convergence tests.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Entanglement remains modest; correct interfacing across languages; consistent finite-size/continuum-limit handling.

- Device design intuition for qubit architectures and trapped systems

- Sector: quantum hardware; advanced manufacturing

- What: Translate the “increasing level spacing” behavior of positive quartic potentials into design heuristics for qubit anharmonicity (e.g., fluxonium regimes, Josephson arrays), trapped ions, and cold-atom optical traps to better isolate low-lying states.

- Tools/workflows: Numerical potential shaping; spectroscopy simulations to assess level spacing trends and leakage mitigation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Mapping from simplified oscillator models to device potentials; engineering control over circuit/trap parameters; environmental noise not dominating.

- Photonics and nanoelectronics: transfer-matrix design of layered structures

- Sector: semiconductors; photonics

- What: Apply the double-barrier transfer-matrix and Wigner time-delay workflows to design resonant tunneling diodes, nanostructured filters, and multilayer optical components with targeted transmission and dwell times.

- Tools/workflows: Parameter sweeps over barrier heights/widths; phase analysis for delay optimization; export to device CAD.

- Assumptions/dependencies: 1D model approximations; adaptation to multimode 2D/3D structures and material dispersion.

- Research workflows for nonperturbative physics in 1+1D

- Sector: academia

- What: Rapid prototyping of scattering and particle-production studies in , Ising field theory, and bosonized Schwinger/Thirring models; validate semiclassical (instantons) against numerics.

- Tools/workflows: Combined semiclassical + exact diagonalization + MPS + QC-simulator pipeline; trans-series awareness for divergent perturbation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Finite-lattice discretization and continuum extrapolation handled carefully; results limited to 1+1D.

- Error modeling for NISQ preparedness

- Sector: quantum computing industry

- What: Use Qiskit-based noise models to anticipate outcomes on IBM-like NISQ devices—estimate gate-depth tolerance, error-mitigation effectiveness, and sensitivity of phase estimation/spectroscopy to decoherence.

- Tools/workflows: Qiskit Aer noise channels; sensitivity analyses; calibration-style benchmark scenarios using oscillator targets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Actual device noise statistics may differ; no hardware runs included in the paper.

- AI-in-research practice guidelines

- Sector: academia; policy

- What: Adopt the authors’ “trust-but-verify” workflow for AI-assisted literature review and coding: enforce unit tests, API audits, and independent derivations when using LLMs.

- Tools/workflows: Code review checklists; CI pipelines with numerical validations; instructor/research group policies on AI-generated content.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Institutional buy-in; evolving LLM reliability.

- Molecular and materials education using Morse and anharmonic potentials

- Sector: education; materials

- What: Demonstrate decreasing versus increasing level spacings using Morse and quartic models; use to teach spectroscopy, phonon hardening/softening, and nonlinear oscillators.

- Tools/workflows: Ready-to-run numerical scripts and visualization notebooks; curated assignments comparing models.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Educational context; limited direct industrial design without further material-specific modeling.

- Reproducibility kits for student projects and capstones

- Sector: education

- What: Package the repository’s scripts into student-ready projects: spectrum extraction, instanton splitting validation, transfer-matrix scattering, and MPS/QC benchmarking.

- Tools/workflows: GitHub Actions for CI; templated notebooks; rubric-aligned deliverables.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Teaching support; consistent environment setup across student machines.

Long-Term Applications

These items require further research, scaling, hardware access, or standardization before wide deployment.

- Scalable real-time quantum simulations of nonperturbative QFT

- Sector: academia; quantum industry

- What: Execute scattering and particle production in 1+1D gauge theories (e.g., Schwinger model) on real quantum hardware; extend to higher dimensions and stronger entanglement.

- Tools/products: Hardware-validated pipelines for QPE/QFT/LCU; error-mitigated dynamics; custom initial-state preparation from interacting vacua.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Larger, more coherent devices; advanced error correction/mitigation; efficient encodings and resource estimates.

- Physics-grounded benchmarking standards for NISQ and beyond

- Sector: standards; policy; quantum industry

- What: Create a cross-vendor “QFT-Bench” suite based on oscillator/double-well targets, instanton splittings, and scattering observables; certify performance across platforms.

- Tools/products: Open standard datasets, protocols, and leaderboards; automated validation harnesses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community agreement on metrics; maintenance body; device access.

- Hybrid TN–QC algorithms for error mitigation and state preparation

- Sector: software; quantum industry

- What: Use MPS to seed variational ansätze, provide compressed representations, and guide error mitigation; dynamic embedding to partition hard subspaces to QC and easy subspaces to TN.

- Tools/products: Interop libraries bridging Julia TN stacks and Python QC stacks; “TN-seeded VQE/QPE” templates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust inter-language interfaces; scalable MPS for moderate entanglement; workflow orchestration across HPC/QC.

- Quantum-enhanced device design via semiclassical tunneling control

- Sector: quantum hardware; advanced manufacturing

- What: Use instanton-based predictions (splitting vs. barrier shape) to tailor anharmonicity, suppress leakage, and optimize coherence in superconducting circuits, trapped ions, and quantum dots.

- Tools/products: “InstantonBench” design toolkit for potential engineering; multiparameter optimization with physics priors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate mapping from abstract potentials to full device models; inclusion of multi-instanton and environmental effects.

- Photonics/telecom slow-light and delay engineering

- Sector: photonics; telecom

- What: Leverage Wigner time-delay control to design slow-light components, timing buffers, and resonant filters in multilayer metamaterials and quantum cascade structures.

- Tools/products: “WignerDelayAnalyzer” integrated with EM solvers; data-driven optimization for delay-bandwidth trade-offs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Extension from 1D to realistic multi-mode geometries; fabrication tolerances; thermal and nonlinear effects.

- Real-time dynamics of confinement and string breaking on quantum hardware

- Sector: academia; quantum industry

- What: Implement bosonized Schwinger/Thirring models to probe confinement and string breaking with quantum circuits; validate against TN/Monte Carlo.

- Tools/workflows: Gauge-invariant encodings; tailored state preparation; low-depth trotterization or analog simulation platforms.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware scale/coherence; efficient gauge constraints; robust error mitigation.

- Platformized education products and microcredentials

- Sector: education; edtech

- What: Convert the course into interactive MOOCs with auto-graded labs, cloud simulators, and optional hardware backends; issue microcredentials in QC–QFT.

- Tools/products: Courseware platform; cloud execution; credentialing integrations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Funding and sustained maintenance; institutional partnerships; backend costs.

- Policy frameworks for AI-in-research and reproducible quantum software

- Sector: policy; academia

- What: Establish group/institutional guidelines on LLM usage in technical research, code verification, and open-source sustainability; promote cross-language interoperability standards (Python ↔ Julia).

- Tools/products: Best-practice documents; compliance templates; community workshops.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Broad stakeholder engagement; evolving legal/ethical landscape.

- Cross-industry toolchains for physics-informed algorithm design

- Sector: software; HPC; quantum industry

- What: Create end-to-end toolchains coupling physics priors (instantons, trans-series behavior) with optimization and ML to accelerate algorithm design (e.g., variational ansätze, error-mitigation schedules).

- Tools/products: “Physics-to-Algorithm” pipelines; ML-guided parameter sweeps; integrated experiment design.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data availability; validation against hardware; sustainable integration costs.

- Extending from 1+1D to materials and chemistry models

- Sector: materials; chemistry

- What: Adapt the pedagogy and workflows to realistic lattice models and molecular Hamiltonians; incorporate anharmonic and Morse-type potentials in vibrational spectroscopy and sensor design.

- Tools/products: Domain-adapted libraries; benchmarking packs for spectroscopy and transport.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Advanced electronic-structure integrations; scalable encodings; tighter coupling with experimental data.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.