FineGRAIN: Evaluating Failure Modes of Text-to-Image Models with Vision Language Model Judges (2512.02161v1)

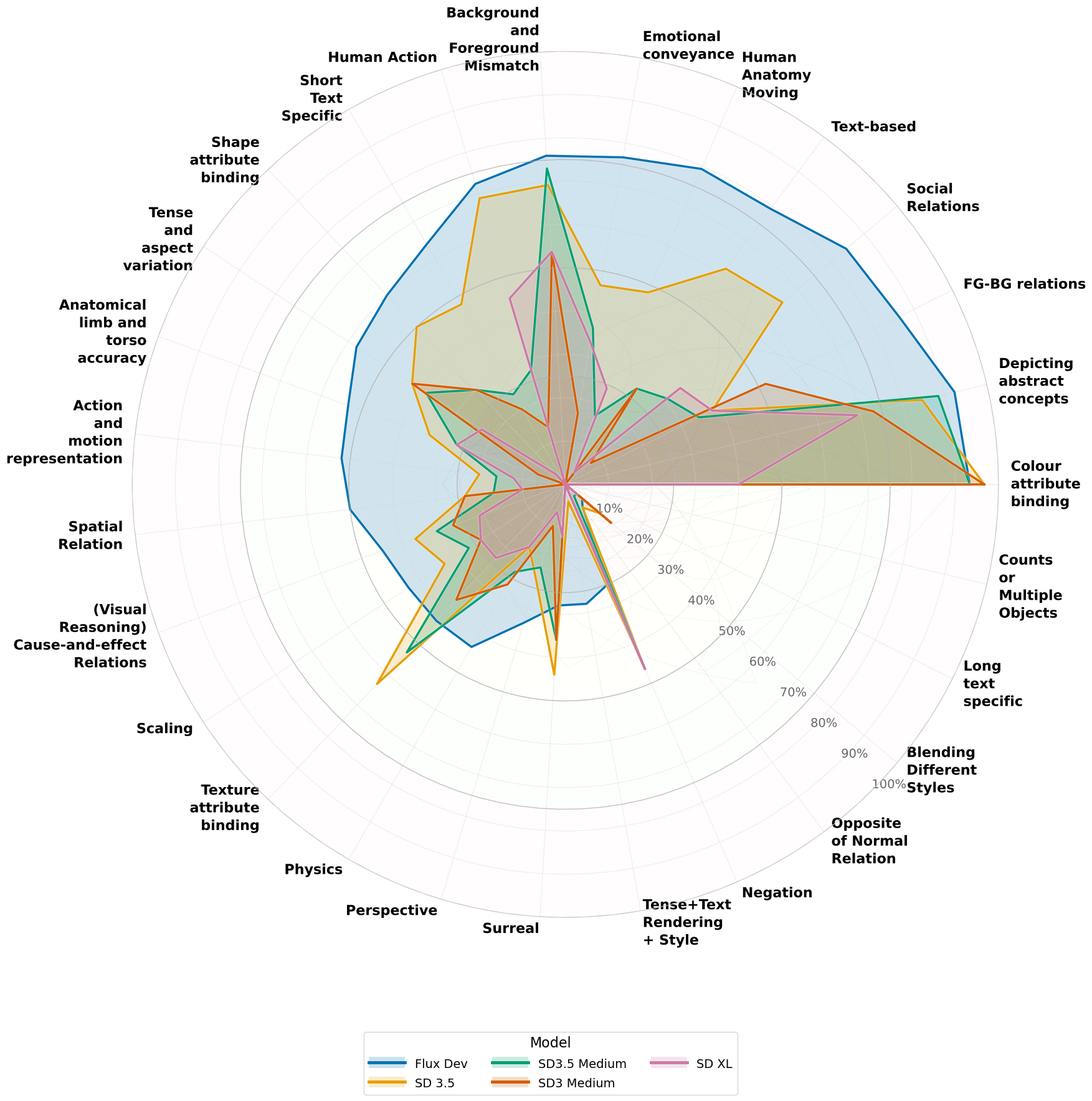

Abstract: Text-to-image (T2I) models are capable of generating visually impressive images, yet they often fail to accurately capture specific attributes in user prompts, such as the correct number of objects with the specified colors. The diversity of such errors underscores the need for a hierarchical evaluation framework that can compare prompt adherence abilities of different image generation models. Simultaneously, benchmarks of vision LLMs (VLMs) have not kept pace with the complexity of scenes that VLMs are used to annotate. In this work, we propose a structured methodology for jointly evaluating T2I models and VLMs by testing whether VLMs can identify 27 specific failure modes in the images generated by T2I models conditioned on challenging prompts. Our second contribution is a dataset of prompts and images generated by 5 T2I models (Flux, SD3-Medium, SD3-Large, SD3.5-Medium, SD3.5-Large) and the corresponding annotations from VLMs (Molmo, InternVL3, Pixtral) annotated by an LLM (Llama3) to test whether VLMs correctly identify the failure mode in a generated image. By analyzing failure modes on a curated set of prompts, we reveal systematic errors in attribute fidelity and object representation. Our findings suggest that current metrics are insufficient to capture these nuanced errors, highlighting the importance of targeted benchmarks for advancing generative model reliability and interpretability.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces FineGRAIN, a new way to test how well AI models that make images from text (called text-to-image or T2I models) follow detailed instructions. It also tests how well AI models that look at images and read text (called vision-LLMs or VLMs) can spot mistakes in those generated images. The goal is to find and measure specific kinds of errors—like the wrong number of objects, wrong colors, or bad text rendering—so developers can fix them.

What questions did the paper ask?

The paper asks simple, practical questions:

- When you tell a T2I model to create a picture (like “three red balloons on a table”), does it actually follow the instructions?

- Can VLMs correctly find and explain the mistakes in those images?

- Which types of mistakes happen most often, and for which models?

- Are current popular scoring methods good enough to catch these specific errors?

How did they do it?

Think of FineGRAIN like a careful referee with a checklist:

- A T2I model makes an image from a prompt (for example: “three blue cats on a sofa”).

- An LLM (a text-based AI) turns that prompt into a clear question for a VLM (like “How many cats are in the image?”).

- The VLM looks at the image and answers the question (“two cats”).

- The LLM compares the VLM’s answer to the original prompt. If it doesn’t match (the prompt said three, the image has two), it marks it as a failure.

This process gives:

- A simple yes/no (boolean) score: Did the image follow the instructions?

- A more detailed score for ranking images.

- An explanation of the mistake (so it’s easy to understand what went wrong).

To make the test fair and thorough, the authors:

- Defined 27 specific “failure modes” (types of mistakes), such as counting objects, binding colors correctly, rendering text, human anatomy, spatial relations, physics (like magnification), and more.

- Wrote 25–30 prompts for each failure mode to cover lots of situations.

- Generated over 3,750 images at high resolution (1360×768) using 5 T2I models: Flux, SD3-Medium, SD3-Large, SD3.5-Medium, SD3.5-Large.

- Asked 3 VLMs (Molmo, InternVL3, Pixtral) to judge the images, with an LLM (Llama3) coordinating the questions and checking answers.

- Collected human labels for each image (1 = contains the failure, 0 = no failure) to compare AI judgments to real people.

In everyday terms: they built a team of AIs—the image-maker, the image-checker, and the text coach—to test and explain where pictures go wrong, and verified it all with human judges.

What did they find and why is it important?

The main findings show specific weaknesses that matter for real use:

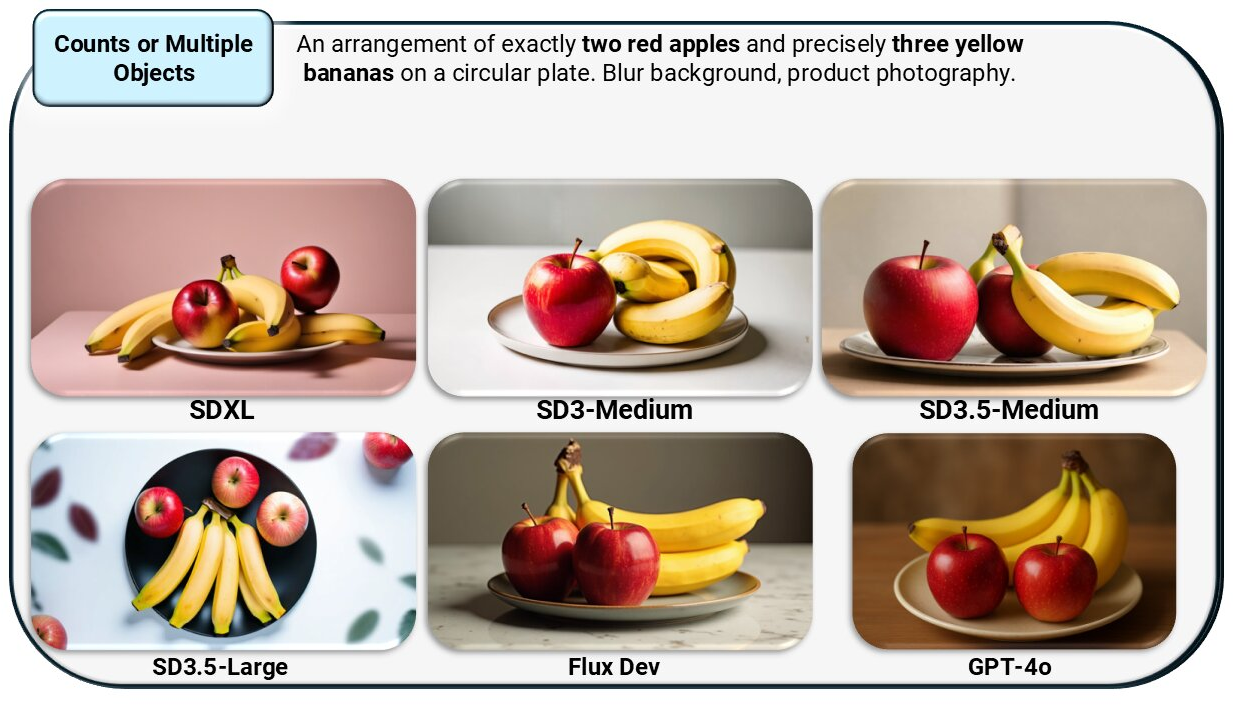

- Counting is very hard: All tested T2I models failed to reliably produce the correct number of objects when asked for multiple items (for “Counts or Multiple Objects,” success was 0% across models).

- Long text in images is also very hard: Models could sometimes render short text (3 words) but failed badly as text got longer (10, 20, 50 tokens), dropping to near 0% success for longer text.

- Short text can work: Some models, like Flux and SD3.5-Large, did better on short phrases.

- Overall performance varies: Flux generally scored highest across failure modes (about 51% average success), but there were still many categories with low scores.

- FineGRAIN’s judges beat older metrics: FineGRAIN’s method matched human judgments about 67% of the time, compared to about 58% for a popular older metric called VQAScore. That means FineGRAIN is better at catching real mistakes humans care about.

- Adjustable difficulty: By changing prompts (more objects or longer text), FineGRAIN can make the test easier or harder, showing clear performance drop-offs as tasks become more complex.

Why it matters:

- These are the kinds of errors users actually care about (like “Did it draw three bananas?”). Current scoring tools often miss these fine-grained issues.

- The boolean (yes/no) score makes it possible to automatically retry image generation until it’s correct, improving reliability in practical systems.

- The explanations help developers pinpoint and fix specific problems, making models more trustworthy.

Implications and potential impact

FineGRAIN gives AI developers a powerful, practical toolkit to:

- Diagnose exact weak spots (like counting, color accuracy, text rendering, human anatomy).

- Compare different models in a fair, detailed way.

- Improve models faster by targeting the most common mistakes.

- Build more reliable image-generation systems that adhere to user instructions.

Broader impact:

- Better testing makes generative AI more consistent and safer to use, especially in areas like design, education, and accessibility.

- At the same time, as image-generation improves, it could become harder to tell real images from fake ones—so stronger evaluation and transparency matter.

In short, FineGRAIN helps move from “this image looks good” to “this image actually follows the rules,” which is essential for trustworthy, useful AI. The dataset and tools are available at finegrainbench.ai, making it easier for others to build on this work.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper. Each point is phrased to be actionable for future research.

- Human annotation reliability is not characterized (e.g., number of annotators, inter-annotator agreement, adjudication procedures), leaving uncertainty about ground-truth quality and consistency across failure modes.

- Several failure modes (e.g., Surreal, Emotional conveyance, Depicting abstract concepts) are inherently subjective; the paper does not formalize operational definitions or decision criteria to make labels reproducible.

- Dataset scale and diversity appear limited (~3,750 images; 25–30 prompts per failure mode), with unclear coverage across object categories, scene types, complexity, and real-world distributions of user prompts.

- The deliberate focus on “challenging-but-doable” prompts (filtering for at least one success and one failure) may bias evaluation and agreement rates; the impact of this selection criterion on generalizability is untested.

- Prompts are English-only and appear to use Latin scripts; performance and failure profiling for multilingual prompts, non-Latin scripts, and cross-lingual settings remains unexplored.

- Image resolution is fixed at 1360×768; the influence of resolution on failure rates—especially text rendering, small object detection, and counting—is not evaluated.

- Counting evaluation is shallow in the main text (ablation only up to three objects); performance on higher counts, occlusion/clutter, overlapping instances, and crowd scenes is not systematically studied.

- Text rendering evaluation varies token length but not typography factors (e.g., fonts, kerning, text curvature on 3D surfaces, complex backgrounds, contrast), limiting insight into realistic text integration challenges.

- The proposed “generate until compliance” test-time scaling strategy is not empirically validated (e.g., success vs. sample budget curves, latency/compute cost, diminishing returns across failure modes).

- The judge architecture conflates VLM and LLM contributions; error attribution between the VLM’s visual reasoning and the LLM’s comparison/judgment is not disentangled or quantified.

- Only one LLM (Llama3-70B) is used; there is no ablation across alternative judges (sizes, families, closed-source) to assess robustness, calibration, and potential biases of the judge component.

- The paper evaluates three open-weight VLMs (Molmo, InternVL, Pixtral) but lacks systematic per-model analysis in the main text; closed-source VLMs are excluded, leaving gaps in understanding of broader judge performance.

- FineGRAIN’s “raw score” (e.g., 8.0 in examples) is introduced but its scale, calibration, mapping to human judgments, and cross-category consistency are unspecified, limiting interpretability and comparability.

- Comparisons to VQAScore rely on a fixed global threshold (0.9) in the main text; the fairness and optimality of category-specific thresholds or calibration procedures are not fully explored.

- The paper suggests FineGRAIN as a reward model for improving T2I, but provides no experiments on training with FineGRAIN-based rewards (e.g., RL or preference optimization) or analyses of reward hacking susceptibility.

- Template-driven instruction generation for VLM questions is not stress-tested for complex prompts (nested negations, co-reference, compositional constraints involving multiple attributes/relations) or template failure cases.

- Each prompt is tagged with exactly one failure mode, but real prompts often require multi-label evaluation; detection and annotation of multiple simultaneous failures is not supported or studied.

- Differences between T2I models are reported without statistical significance testing, confidence intervals per failure mode, or power analyses, leaving uncertainty about the robustness of model rankings.

- T2I sampling/generation settings (e.g., seeds, guidance scale, sampler, steps) and their effects on failure rates are not documented; the sensitivity of compliance to generation hyperparameters is unknown.

- Safety, bias, and demographic fairness are not assessed (e.g., “Human” categories across age, skin tone, body type, gender presentation); harmful content and ethical constraints in prompts/labels are unaddressed.

- FineGRAIN’s portability to non-synthetic inputs (real photos or edited images) is not evaluated; it is unclear if the judges generalize from generated images to real-world imagery.

- Labeling guidelines for edge cases (partial visibility, occlusion, background instances, tightly overlapping objects, “what counts as an object” in counting) are not specified, risking inconsistent ground truth.

- Details of data/code release (complete prompt templates, human labels, VLM/LLM outputs, seeds, generation configs, licensing, reproducibility artifacts) are not fully described in the main text.

- Agreement patterns suggest FineGRAIN aligns better with specific T2I styles (e.g., Flux); potential style biases or calibration issues across models are not investigated.

- Temporal and causal failure modes are defined for static images; the validity of ground truth and judge assessments for inherently temporal phenomena (e.g., cause-and-effect, tense/aspect) is unclear without video data or temporal context.

Glossary

- Ablation: A controlled analysis that varies or removes components to measure their effect on performance. "we ablate this threshold in the Appendix"

- Adversarial prompts: Intentionally challenging instructions designed to expose model weaknesses. "propose an instruction following benchmark for T2I models that focuses on what they call ``adversarial'' prompts."

- Agentic system: A system composed of autonomous agents coordinating to perform evaluation or decision-making tasks. "FineGRAIN is an agentic system for rating Text-to-Image and Image-to-Text models"

- Attribute binding: Correctly associating attributes (e.g., color, shape, texture) with the specified objects in an image. "Color attribute binding, Shape attribute binding, Texture attribute binding"

- Background and Foreground Mismatch: Inconsistency between the subject (foreground) and the scene (background), leading to unrealistic or incorrect compositions. "Background and Foreground Mismatch"

- Boolean score: A binary indicator (0 or 1) representing whether a condition (e.g., prompt compliance) is met. "The corresponding boolean score is $1$, indicating that the failure mode~(in this case, long text generation) is present."

- CLIPScore: A reference-free metric based on CLIP that measures image–text alignment. "such as CLIPScore~\citep{hessel2021clipscore} and PickScore~\citep{kirstain2023pick}"

- Compositional reasoning: The ability to reason about complex scenes composed of multiple objects, attributes, and relations. "VLMs still lack key capabilities, particularly in compositional reasoning."

- Conditioning signals: Auxiliary inputs (beyond text) used to control generative models, such as audio or resolution. "the design of conditioned image generative models can support a wide range of conditioning signals"

- Counts or Multiple Objects: A failure mode concerned with generating the correct number of objects specified by a prompt. "All models fail completely to generate ``Counts or Multiple Objects'' so we know that these models struggle to generate the correct numbers of objects."

- Diffusion-based generative models: Image generation models that iteratively denoise data from noise to produce samples conditioned on inputs. "we primarily evaluate the capabilities of open- source diffusion-based generative models"

- Diffusion transformer architectures: Transformer-based architectures adapted to diffusion modeling for large-scale image generation. "Most large-scale T2I models now commonly employ diffusion transformer architectures"

- FG-BG relations: Relationships and coherence between foreground objects and the background in an image. "FG-BG relations"

- LLM: A high-capacity text model used to generate, interpret, and judge instructions and outputs. "An LLM automatically creates the ``How many dogs are in this image?'' prompt for the VLM"

- Multimodal guidance: Leveraging multiple data modalities (e.g., text and image) to guide model predictions or evaluations. "Another advantage VLM models have over text-to-image modes is that they have multimodal guidance."

- Ontology (of failure modes): A structured taxonomy organizing and defining categories of model failures. "An Ontology of Failure Modes"

- Out-of-distribution data: Inputs that differ significantly from the training distribution, often causing model failures. "biased towards out-of-distribution data."

- PickScore: A metric derived from user preferences to evaluate text-to-image outputs. "such as CLIPScore~\citep{hessel2021clipscore} and PickScore~\citep{kirstain2023pick}"

- Prompt adherence: The extent to which generated outputs faithfully follow the specified instructions. "continue to face challenges with prompt adherence."

- Prompt fidelity: The precision with which a model satisfies detailed and specific prompt requirements. "where prompt fidelity is critical."

- Reward hacking: Exploiting the reward function to achieve high scores without genuinely solving the task. "mitigate its challenges like reward hacking for a given failure mode."

- Reward modeling: Using models to compute or predict rewards for training or evaluating generative systems. "better understand the opportunities of T2I reward modeling"

- ROC curve: A plot of true positive rate versus false positive rate across decision thresholds for evaluating binary classifiers. "We provide a full ROC curve for VQAScore in the Appendix."

- Test-time scaling: Improving results by repeated generation/evaluation during inference to find a compliant output. "This is an element of test-time scaling that we contend will be especially valuable for T2I deployments."

- Thresholding: Converting a continuous score to a binary decision using a cutoff value. "We convert VQAScore to a boolean by thresholding it at $0.9$."

- Token: A minimal unit of text used by LLMs; often used to quantify prompt length. "three-token prompts"

- Text-to-Image (T2I) models: Models that generate images conditioned on textual descriptions. "Text-to-image (T2I) models are capable of generating visually impressive images"

- Vision-LLMs (VLMs): Models that jointly process visual and textual inputs to understand and reason across modalities. "Vision-LLMs (VLMs) have become essential tools in multimodal AI"

- VQAScore: A metric that uses visual question answering to estimate whether an image contains the specified text content. "VQAScore is a metric that takes in an image and a text and outputs the likelihood that the image contains the text."

Practical Applications

Overview

Below are practical, real-world applications that leverage FineGRAIN’s findings, methods, and innovations. Each item specifies sector links, potential tools/workflows, and assumptions or dependencies affecting feasibility.

Immediate Applications

- Prompt fidelity checker for production T2I pipelines

- Use case: Automatically validate whether generated images match user specs (counts, colors, text, relations), then “regenerate until pass.”

- Sectors: software, creative industries, advertising, gaming, e-commerce.

- Tools/workflows: FineGRAIN API/SDK; Generate → Judge (VLM+LLM boolean) → Regenerate loop; CI checks in ComfyUI/Automatic1111/Photoshop plugin.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to a capable VLM/LLM; compute overhead for multiple generations; threshold tuning for booleans; domain-specific prompt templates may be needed.

- Model evaluation and procurement dashboard for T2I/VLM vendors

- Use case: Rank models by failure-mode profile (e.g., text rendering, counting, spatial relations) to inform purchasing and integration decisions.

- Sectors: software, enterprise IT, platform teams.

- Tools/workflows: FineGRAIN benchmark integration; model cards extension with failure-mode metrics; periodic audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Benchmark representativeness; reproducible evaluations; updates as models evolve.

- Creative QA automation for agencies and studios

- Use case: Automatically detect objective errors (wrong counts, color bindings, illegible text) before delivery; attach interpretable failure explanations.

- Sectors: advertising, media, entertainment, publishing.

- Tools/workflows: Batch image validation; routing failed assets to human review with LLM rationale; ticketing integration (Jira/Asana).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Some categories (e.g., “Surreal”) remain subjective; human-in-the-loop needed for borderline cases.

- E-commerce product imagery validator

- Use case: Enforce exact counts (e.g., “set of 3 glasses”), color and style adherence, and legible on-image text (labels, sizes).

- Sectors: retail, marketplaces, consumer goods.

- Tools/workflows: SKU-specific prompt templates; catalog compliance checks; auto-rejection reasons; regeneration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate product specifications; robust VLM detection under occlusion or clutter.

- Accessibility and text legibility checks for generated UI/brand assets

- Use case: Verify short text readability and correct rendering styles on posters, signage, UI mockups.

- Sectors: design systems, product design, brand management.

- Tools/workflows: Short-text and style-focused failure modes; contrast/legibility heuristics plus VLM judgments; design pipeline gating.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Long text remains hard for current T2I; fallback to compositor/text-overlays may be necessary.

- RLHF-style reward modeling for T2I (prompt adherence optimization)

- Use case: Use FineGRAIN’s boolean and raw scores as rewards to fine-tune models for compositional accuracy.

- Sectors: AI model development, ML research.

- Tools/workflows: Training loops that target failure modes; curriculum learning using difficulty scaling; anti–reward hacking checks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable reward signal; careful design to avoid gaming the metric; compute costs.

- Difficulty-controlled benchmarking for academic evaluation

- Use case: Programmatically increase prompt complexity (longer text, more objects) to study generalization and compositional limits.

- Sectors: academia, research labs.

- Tools/workflows: Public dataset and benchmarks; prompt ladders; comparisons vs. VQAScore/CLIPScore.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to benchmark (finegrainbench.ai); consistent protocol; diverse models.

- Governance and compliance reporting for generative pipelines

- Use case: Include failure-mode adherence metrics in risk registers, model cards, and audit trails.

- Sectors: policy, compliance, enterprise IT governance.

- Tools/workflows: Automated logs of pass/fail by category; trend analyses; deployment gates (e.g., counts/color/text categories must meet targets).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational buy-in; mapping categories to risk; ongoing monitoring.

- Content moderation complement (objective checks)

- Use case: Complement safety filters with objective conformance checks (e.g., “no text errors,” “no miscounts”) for higher reliability.

- Sectors: social platforms, content hosting.

- Tools/workflows: Two-stage filtering: safety → fidelity; automatic feedback/rationale.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Does not replace safety systems; subjective content still needs separate moderation.

Long-Term Applications

- Industry certification standard for “prompt fidelity”

- Use case: Third-party certification that generative systems meet minimum adherence across defined failure modes.

- Sectors: software, procurement, public sector.

- Tools/workflows: Standardized test suites; graded performance tiers; routine audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consensus on benchmarks; accreditation processes; coverage beyond the current 27 modes.

- Self-correcting T2I agents (generate–judge–edit loops)

- Use case: Agents that identify failures and apply targeted corrections (e.g., inpainting missing objects, fixing text via overlays).

- Sectors: creative tooling, design automation, product visualization.

- Tools/workflows: FineGRAIN rationale → automatic prompt rewrite or local edit; control-nets; constraint solvers for counts/relations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable localization of failures; compositional controls; editor APIs; reduced latency.

- Constraint-aware generative pipelines

- Use case: Guarantee counts, spatial relations, and attribute bindings using structured constraints enforced during generation.

- Sectors: manufacturing, architecture, robotics simulation.

- Tools/workflows: Spec-to-image conformance; integrated constraint solvers; scene graphs; programmatic generation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strong controllability of T2I (future models); semantic scene control interfaces; formal specs.

- Robust multi-modal reward shaping to reduce reward hacking

- Use case: Combine objective checks (counts, text) with diverse signals to prevent models from gaming a single metric.

- Sectors: ML research, model training.

- Tools/workflows: Multi-metric rewards; adversarial audits; periodic cross-benchmark validation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of diverse metrics and judges; scalable training.

- Brand asset conformance services

- Use case: Automated verification that generated assets meet brand guidelines (color, typography, layout rules) at scale.

- Sectors: marketing, brand management, enterprise design.

- Tools/workflows: Brand-specific templates; failure-mode maps to brand rules; correction suggestions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Formalized brand specs; accurate detection of styles and typography; domain-tuned VLMs.

- High-fidelity simulation asset generation for robotics and AV

- Use case: Generate synthetic scenes with guaranteed counts, relations, and physics plausibility for training and testing.

- Sectors: robotics, autonomous vehicles.

- Tools/workflows: Physics and spatial relation checks; curriculum difficulty scaling (crowds, occlusions); simulator integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Improved physics-aware T2I; validation against ground-truth simulators; domain transfer reliability.

- Healthcare/biomed synthetic imagery with strict attribute adherence

- Use case: Controlled synthetic data generation for training diagnostic or workflow tools where specified features must appear.

- Sectors: healthcare, medical imaging (with caution).

- Tools/workflows: Failure-mode gates for anatomy, text labels, counts; human-in-the-loop verification.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory approval; medical expert validation; avoiding hallucinations and bias; current models may not meet clinical standards.

- Document/UI generation with guaranteed text accuracy

- Use case: Generate marketing collateral, forms, and interfaces where all text must match specs and be legible.

- Sectors: finance, government services, enterprise software.

- Tools/workflows: Text-specific failure modes; overlay strategies; automated proofreading via VLM+OCR hybrids.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Current T2I struggles with long text; hybrid pipelines mixing T2I with deterministic text rendering.

- Education and benchmarking consortia for compositional reasoning

- Use case: Shared benchmarks and curricula to train models (and practitioners) on fine-grained capabilities.

- Sectors: academia, industry research labs.

- Tools/workflows: Public leaderboards; difficulty ladders; standardized teaching materials built on FineGRAIN.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community adoption; sustained maintenance; expanded coverage across domains.

- Policy frameworks for generative model reliability and transparency

- Use case: Regulatory guidance that requires disclosure of failure-mode performance and testing before deployment at scale.

- Sectors: public policy, standards bodies.

- Tools/workflows: Reporting templates; independent audit requirements; thresholds for high-risk applications.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal adoption; measurement harmonization; mechanisms for ongoing compliance.

Notes on Feasibility

- Dependencies on VLM/LLM accuracy: FineGRAIN’s judgments rely on VLM and LLM capabilities; closed-source models may improve results but increase cost and governance complexity.

- Objective vs. subjective categories: Some failure modes (e.g., “Surreal”) are less objective; human oversight is recommended for production.

- Compute and latency: “Regenerate until pass” increases runtime costs; batching and caching strategies can mitigate overhead.

- Domain adaptation: Templates and thresholds may need tuning per sector or product line; occlusion and clutter pose detection challenges.

- Safety and ethics: FineGRAIN is not a safety filter; it should complement content moderation and risk controls, especially in sensitive domains (healthcare, finance, public sector).

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.