Consistent Synthetic Sequences Unlock Structural Diversity in Fully Atomistic De Novo Protein Design (2512.01976v2)

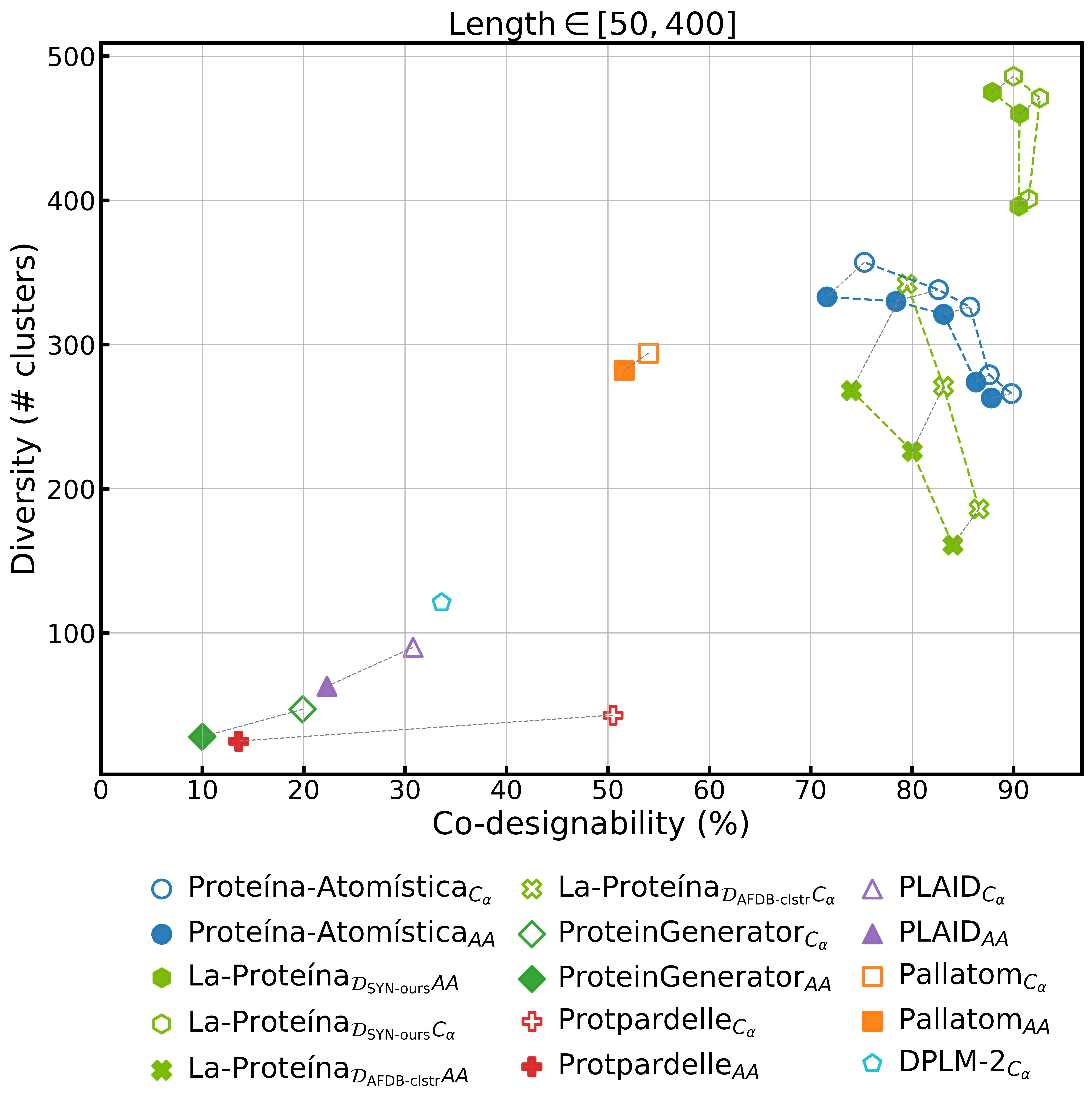

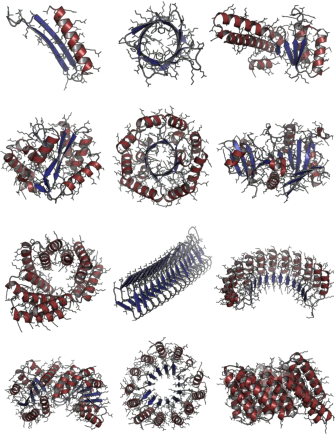

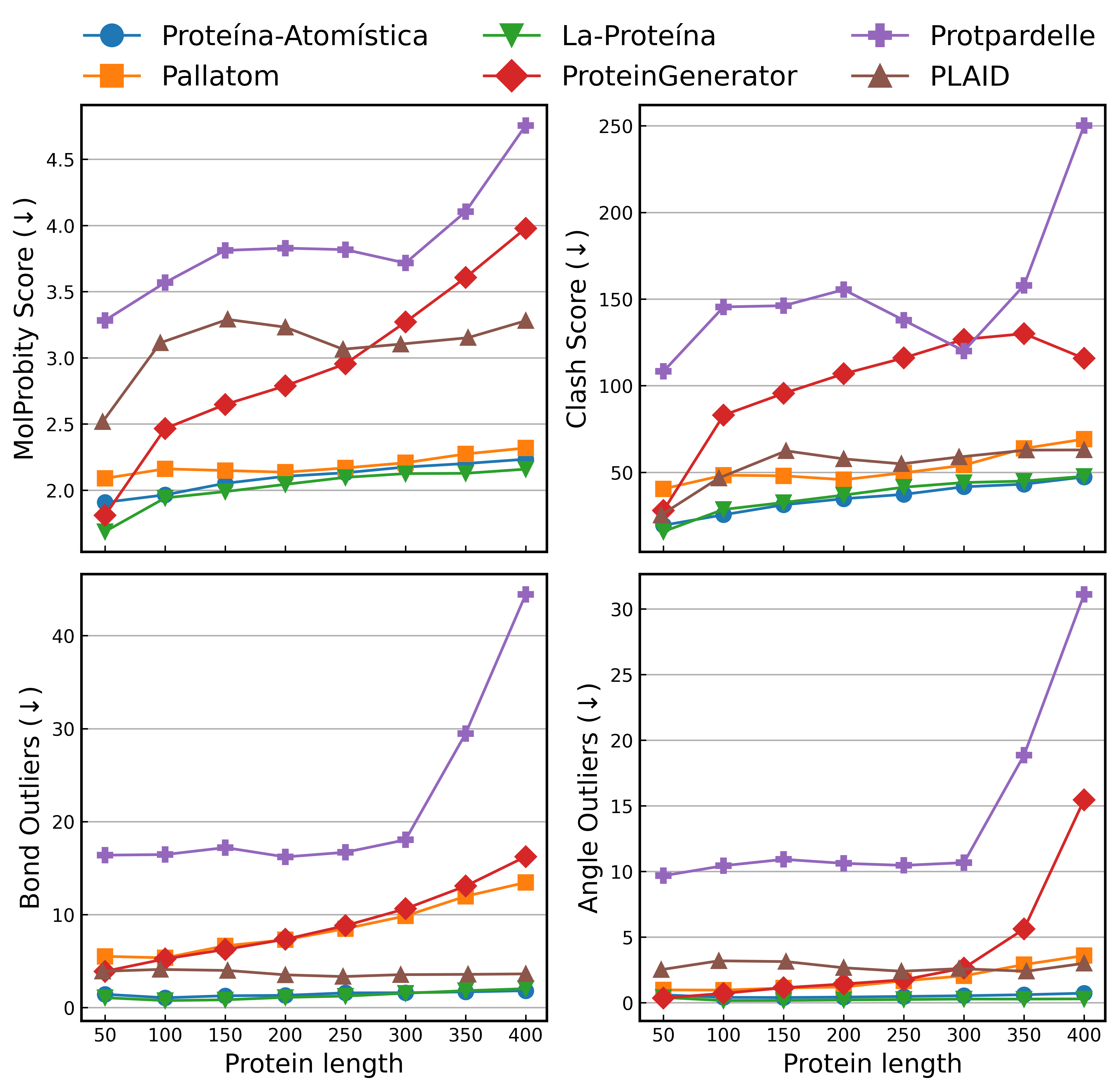

Abstract: High-quality training datasets are crucial for the development of effective protein design models, but existing synthetic datasets often include unfavorable sequence-structure pairs, impairing generative model performance. We leverage ProteinMPNN, whose sequences are experimentally favorable as well as amenable to folding, together with structure prediction models to align high-quality synthetic structures with recoverable synthetic sequences. In that way, we create a new dataset designed specifically for training expressive, fully atomistic protein generators. By retraining La-Proteina, which models discrete residue type and side chain structure in a continuous latent space, on this dataset, we achieve new state-of-the-art results, with improvements of +54% in structural diversity and +27% in co-designability. To validate the broad utility of our approach, we further introduce Proteina Atomistica, a unified flow-based framework that jointly learns the distribution of protein backbone structure, discrete sequences, and atomistic side chains without latent variables. We again find that training on our new sequence-structure data dramatically boosts benchmark performance, improving \method's structural diversity by +73% and co-designability by +5%. Our work highlights the critical importance of aligned sequence-structure data for training high-performance de novo protein design models. All data will be publicly released.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching computers to design brand‑new proteins from scratch. Proteins are tiny machines in our bodies, made from chains of building blocks called amino acids. The authors show that to design realistic proteins with all their atoms in the right places, you need training data where the sequence (the order of amino acids) and the 3D shape truly match. They build a new, better‑aligned dataset and train two advanced models that can generate complete, atom‑by‑atom protein structures together with their sequences. This leads to more diverse and more reliable designs.

What questions does the paper ask?

The paper focuses on three simple questions:

- Can we trust popular protein datasets to train models that design both the sequence and the full 3D structure at the same time?

- If not, can we build a better dataset where sequences and structures truly fit together?

- With that improved data, can we train models that produce realistic, varied, and easy‑to‑recreate proteins, down to every atom?

How did they do it?

Think of a protein like a LEGO creation:

- The “sequence” is the instruction list (which pieces go in which order).

- The “backbone” is the main frame that gives the overall shape.

- The “side chains” are the small parts that stick out and make the protein work properly.

The authors do two big things: they build a better dataset and they train two kinds of design models.

Building a better training set

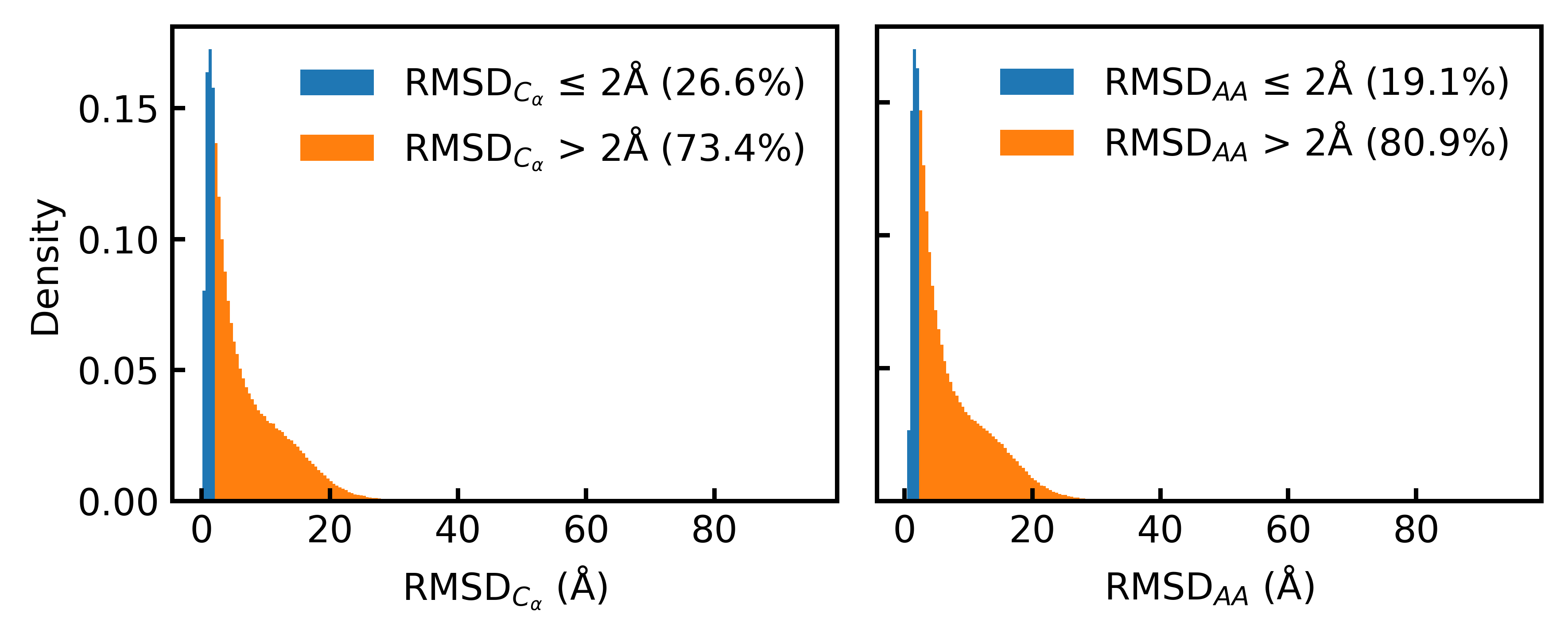

The commonly used AlphaFold Database (AFDB) contains many “synthetic structures” (computer‑predicted shapes) paired with real sequences. Surprisingly, the team found that most of these pairs don’t match well when checked with modern folding tools (only about 19% matched at full‑atom detail under standard checks). That’s a problem: if the training examples aren’t consistent, the model learns the wrong relationship between sequence and shape.

So they made a new dataset:

- Start with a large, diverse set of trusted backbone structures.

- Use a tool called ProteinMPNN to propose several sequences for each structure.

- Refold those sequences with a folding tool (ESMFold) to get the full atom positions.

- Keep only the pairs where the sequence folds back into the original shape with high confidence.

This careful process creates hundreds of thousands of matched sequence–structure examples where both sides agree. In short: they aligned the “recipe” and the “result.”

Two ways to teach a computer to design proteins

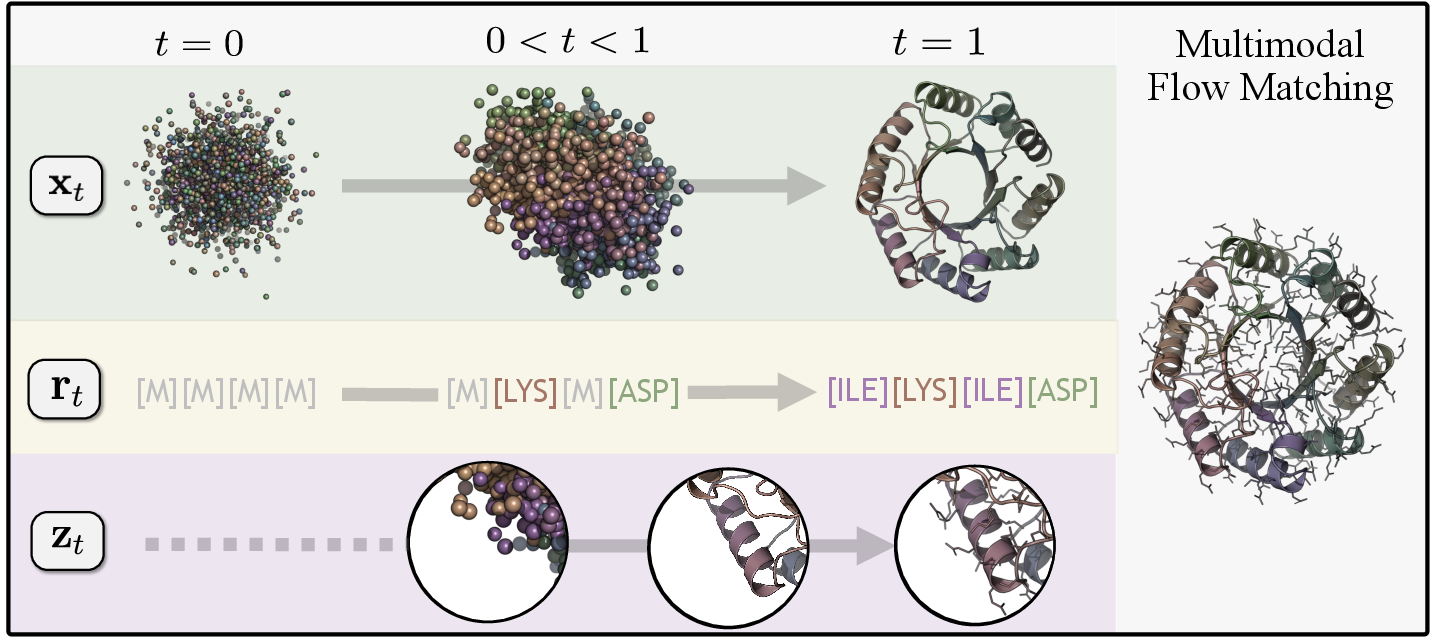

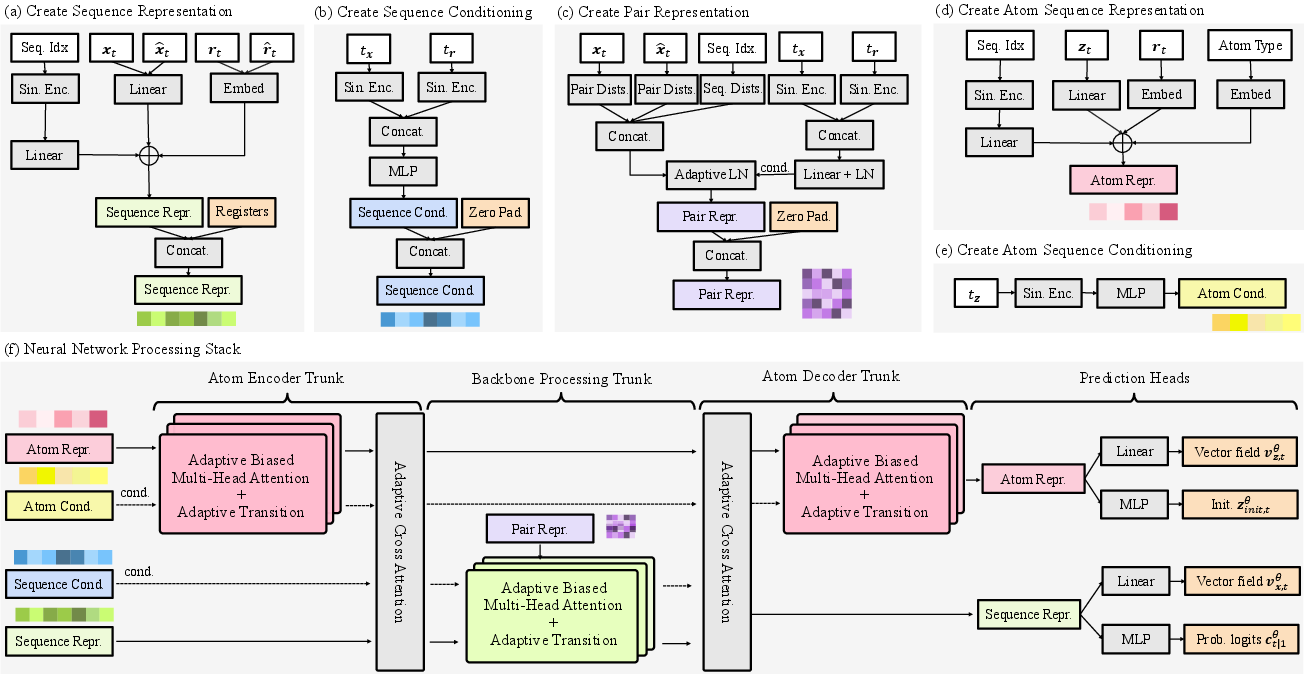

They train and compare two models that generate the backbone, the sequence, and all side‑chain atoms together:

- A latent model (from prior work): It hides some information in a compact “secret code” (a latent space). This makes it easier to learn complex relationships between sequence and structure and then decode them into full atoms.

- A new explicit model called La‑Proteina: It works directly with observable data for all parts—backbone, sequence, and side‑chain atoms—without hiding anything. This is harder, but gives full control and direct access to every atom.

Key ideas behind the models (in everyday terms)

- Gradual construction (flow matching): Imagine turning a blurry fog into a clear picture step by step. Both models start from “noise” and gradually sharpen it into a realistic protein by learning the direction to move at each small step.

- Sequence masking: To pick the amino acids in order, the model starts with a string of “unknown” tokens and reveals them one by one, learning which residues fit the growing structure.

- Side chains after sequence: Side chains (the detailed atoms that define each residue) depend on the residue type. The model only fills them in once it knows the residue, to avoid “cheating” or mixing up information.

- Local coordinates: The model often describes side‑chain atoms relative to their nearby backbone atom (the C‑alpha). This is like giving directions from a known landmark, which makes learning easier and more accurate.

- Atom representation: They use a clear atom layout (Atom37) where every possible heavy atom has a fixed slot. Non‑existent atoms are simply masked out, making the data consistent and avoiding confusion.

What did they discover?

- The original AFDB dataset has many mismatched pairs: Most sequences don’t fold back into the given structures when checked carefully. That’s not good for training models to design both sequence and full atom positions together.

- Their new aligned dataset fixes this: By designing sequences to fit structures and refolding them, they create sequence–structure pairs that are consistent and reliable.

- Models trained on the new dataset get much better:

- Higher “co‑designability”: The generated sequence folds back into the generated structure, down to all atoms, much more often (in their best setting, around 88–93% all‑atom co‑designability).

- Greater structural diversity: The models produce many different shapes and styles, not just repeats of the same thing, while still being foldable.

- Reduced reliance on extra tools: Their models can produce sequences that fold well without needing to redesign the sequences afterward with tools like ProteinMPNN.

- A surprising result: Simply training on structures that are “100% designable” by one folder (like ESMFold) didn’t help if the sequence–structure relationship wasn’t aligned. What matters most is pairing sequences and structures that are proven to fit each other, not just picking “confident” structures alone.

Why is this important?

- Better building blocks for science: Proteins do almost everything in living things—digest food, fight infections, carry signals, and build tissues. Designing new ones could lead to new medicines, cleaner industrial processes, and powerful biosensors.

- Full‑atom detail matters: Side chains are where many important interactions happen (like binding to drug molecules). Generating complete atom‑by‑atom structures is crucial for designing proteins that actually work.

- Data quality is key: The paper shows that a well‑aligned dataset can unlock much bigger improvements than just changing the model. Good training examples help the model learn the true rules of protein folding.

Implications and impact

- Practical protein design: These models, trained on aligned data, are more likely to produce sequences that labs can synthesize and that will fold as intended. That speeds up experimental work and reduces trial‑and‑error.

- More diverse designs: With higher diversity and reliability, scientists can explore a wider “design space” to find proteins for specific jobs, like sticking to a target molecule or catalyzing a chemical reaction.

- A foundation for future tools: The new dataset and modeling ideas can be used in conditional design tasks, such as building scaffolds around a known active site, or designing binders for disease targets.

In short, aligning synthetic sequences with their structures makes computer‑designed proteins more realistic and varied. That insight—combined with powerful generative models—brings us closer to designing useful proteins on demand.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of unresolved issues that, if addressed, could strengthen the paper’s claims and guide future research.

- Wet‑lab validation is absent: no experimental folding, stability, or functional assays for model‑generated sequences and structures; reliance solely on in‑silico metrics leaves true viability and function untested.

- Predictor bias in data curation and evaluation: the dataset uses ESMFold for refolding and pLDDT filtering, and co‑designability metrics depend on ESMFold/ProteinMPNN, potentially biasing both training and evaluation toward these tools’ failure modes and priors.

- Limited cross‑model consistency analysis: while AFDB misalignment is quantified with ESMFold/AF2/ColabFold/Boltz‑1, the new dataset’s consistency is not systematically stress‑tested across multiple predictors (e.g., AF2 with MSAs at scale, RoseTTAFold, Boltz‑1 without MSAs), nor are disagreements analyzed.

- No assessment of physics/chemistry plausibility: bond lengths/angles, stereochemistry, rotamer preferences, steric clashes, hydrogen bonding, side‑chain packing, and overall energy (e.g., Rosetta score, MD relaxation) are not reported for generated atomistic structures.

- Hydrogen atoms and protonation states are not modeled: the approach uses heavy‑atom representations; extension to explicit hydrogens, protonation, tautomers, and pH‑dependent states is left unexplored.

- Disulfides, cofactors, metals, and ligands are ignored: covalent crosslinks, metal coordination, and small‑molecule binding (central to many functional proteins) are not modeled or evaluated.

- Quaternary structure and complexes are not addressed: the framework and dataset focus on single chains; extension to multimers, interface co‑design, and assembly accuracy remains open.

- Beta‑rich fold coverage is unclear: generated outputs are predominantly alpha‑helical (66–70% helices, 6–10% sheets); ability to produce diverse beta‑sheet topologies and correct strand pairing needs targeted evaluation.

- Dataset selection may entrench AFDB biases: “best‑of‑four ProteinMPNN sequences” chosen by Cα RMSD to AFDB cluster representatives could bias toward AFDB’s structural priors; the effect on downstream diversity and novelty is not quantified.

- Sequence sampling breadth is limited: only four ProteinMPNN sequences per structure are considered; scaling sequence sampling and exploring alternative inverse‑folding models (or mixture‑of‑inverse‑folders) could improve coverage and reduce bias.

- Sensitivity to thresholds is untested: pLDDT ≥ 0.8 and RMSD ≤ 2 Å thresholds may materially shape dataset composition and outcomes; sensitivity analyses across thresholds and length ranges are missing.

- Ambiguity leakage risks remain: Atom37 zeros for non‑existent atoms and the use of pseudo‑atoms may leak residue‑type information; while training masks aim to mitigate this, leakage and its impact are not quantified.

- Initialization head may introduce unrealistic intermediates: predicting an average side‑chain structure across 20 residue types for masked residues could yield chemically implausible transient states; the effect on final quality and failure cases is not analyzed.

- Theoretical grounding of discrete–continuous joint flow is limited: the discrete masking path for sequences and continuous flows for coordinates lack a rigorous joint probabilistic or CTMC‑coupling analysis; guarantees on learned joint distributions and cross‑consistency are not provided.

- Non‑equivariant architecture choice is under‑justified: La‑Proteina’s non‑equivariant trunk omits geometric equivariance and triangle updates; the impact on long‑range constraints and global consistency vs. SE(3)‑equivariant alternatives is not benchmarked.

- Local coordinate strategy trade‑offs are under‑explored: two local schemes (offsets vs. local frames) are introduced, but their effects on accuracy, stability, and generalization (especially for long proteins) need deeper analysis.

- Length scaling limitations: La‑Proteina shows reduced co‑designability at longer lengths; mechanisms and architectural/training changes to robustly scale beyond 400–500 residues are not proposed or tested.

- Conditional design tasks are not evaluated: motif scaffolding, binder design, enzyme active‑site preservation, and property‑conditioned generation (e.g., stability, solubility, charge) are mentioned as future work but lack empirical validation.

- Property control is absent: the models do not offer controllable generation for biophysical attributes (e.g., thermostability, aggregation propensity, expression yield, immunogenicity); pathways for conditioning or multi‑objective optimization are open.

- Fairness of baseline comparisons: many baselines are trained on different datasets; re‑training baselines on the new aligned dataset to isolate model vs. data contributions is missing.

- Novelty metric interpretation needs clarity: novelty scores are reported but their calibration, sensitivity to AFDB/PDB overlap, and relation to functional novelty (not just structural dissimilarity) are not dissected.

- Robustness to label noise and predictor errors: AFDB/ESMFold predictions contain uncertainty; the model’s robustness to noisy coordinates/sequences and misfolds is not quantified; data clean‑up strategies are unexplored.

- Domain architecture and multi‑domain proteins: handling of multi‑domain chains, flexible linkers, and domain boundaries is not explicitly characterized or benchmarked.

- Reproducibility and data governance details: full pipeline reproducibility (code, parameters, seeds), licensing constraints, provenance, and ethical/safety screening for potentially harmful proteins are not detailed.

- Computational cost and efficiency: training/inference time, memory, and scaling behavior for the 200M‑parameter models are not reported; trade‑offs vs. latent models (i) require quantitative analysis.

- Confidence calibration: the models do not provide calibrated confidence or uncertainty estimates analogous to pLDDT; methods to quantify uncertainty in generated sequences/structures remain an open need.

- Interpretability and control of latent representations (for i): how latent variables map to sequence/structure features, and how to steer them toward desired properties, is not analyzed.

- Post‑generation refinement: the role of downstream physics‑based relaxation or structure correction (e.g., AlphaFold3‑style refinement, Rosetta minimization, MD) in improving atomistic fidelity has not been assessed.

- Generalization to natural proteins: benchmarks specifically targeting recovery or redesign of experimentally resolved PDB structures (with held‑out families) are not reported for the fully atomistic co‑design setting.

Glossary

- AFDB: The AlphaFold Database of computationally predicted protein structures used as a large training corpus. "derived from the AlphaFold Database (AFDB)"

- AlphaFold2 (AF2): A deep learning system that predicts protein structures with high accuracy. "under AlphaFold2 (AF2)~\citep{jumper2019alphafold2, Mirdita2022}"

- All-Atom Co-designability (CODES-AA): A metric assessing whether a generated sequence folds into its co-generated full atomistic structure, typically via all-atom RMSD/scRMSD thresholds. "All-Atom Co-designability (CODES-AA), an extension of CODES using all-atom scRMSD."

- Atom14 representation: A compact structural encoding with 14 atom positions per residue that can introduce atom-type ambiguities. "Pallatom's~\citep{qu2024pallatom} use of Atom14 representations could lead to atom-type ambiguities"

- Atom37 representation: A per-residue structural encoding assigning a unique slot to each potential heavy atom, avoiding ambiguities. "we adopt the Atom37 representation for protein structures"

- Autoencoder: A neural network that learns a compressed latent representation and reconstruction of data, used here to encode sequences and side-chain details. "through the training of an initial autoencoder."

- Backbone: The main chain of a protein’s structure (e.g., N–Cα–C), defining global fold and geometry. "inverse fold the generated protein backbone"

- Boltz-1: A biomolecular modeling system for structure prediction and design used as a baseline. "or Boltz-1~\citep{wohlwend2024boltz1},"

- Cα coordinates: The 3D positions of alpha-carbon atoms, representing coarse protein backbone geometry. "Flow Matching for Atoms."

- Conditional Flow Matching (CFM): A training objective for flow models that matches model velocities to tractable conditional paths between noise and data. "conditional flow matching (CFM) constructs for each data sample a tractable conditional path"

- Co-designability: The property that a sequence and structure are mutually consistent so the sequence folds into the target structure. "Co-designability of D."

- ColabFold: A fast, accessible pipeline for protein folding powered by AlphaFold2 and MSAs. "even the best co-designability achieved, with ColabFold using MSAs,"

- Continuity equation: The PDE relating time evolution of a probability density to the divergence of probability flow in generative flow models. "By the continuity equation, the true vector field satisfies $\partial p_t/\partial t = -\nabla_{_t}\cdot\bigl(p_t\,_t\bigr)$"

- Cross-attention: An attention mechanism that fuses information across modalities (e.g., residues and atoms). "followed by a cross-attention layer that integrates residue and atom features"

- De novo protein design: Designing functional proteins from scratch without starting from natural sequences. "De novo protein design aims to generate functional proteins from scratch"

- Designability (DES-M1): A single-shot metric evaluating whether inverse-folded sequences refold to the generated backbone. "DES-M1 (single-shot)"

- Designability (DES-M8): A metric using the best of eight inverse-folded sequences to assess if they refold to the generated backbone. "DES-M8 (standard for backbone-only; best of 8 sequences)"

- Diversity: A measure of structural variety among a set of generated, designable proteins. "structural diversity by 73\%"

- ESMFold: A protein structure prediction model based on LLMs for proteins. "folding its sequences (length[32,256]) with ESMFold"

- Foldseek: A fast protein structure search and clustering tool used to obtain representative structures. "Foldseek AFDB cluster representative structure"

- Flow matching: A generative modeling approach that learns a velocity field to transport a simple distribution to the data distribution. "By applying flow matching in this partially latent space"

- Gram-Schmidt process: A method for constructing orthonormal bases, used here to build local residue-centric frames. "via the Gram-Schmidt process."

- Heavy atom: Non-hydrogen atoms in a protein structure (e.g., C, N, O, S) used in atomistic representations. "each potential heavy atom of a residue is assigned a unique position within a 37-dimensional array."

- In silico: Computational experiments or validations performed on computers rather than in wet lab. "known for strong in silico success"

- Inverse folding: Predicting a sequence that folds into a given target backbone structure. "inverse fold the generated protein backbone"

- La-Proteina: A unified multi-modal flow-based generator that explicitly co-designs sequence, backbone, and side chains. "La-Proteina achieves fully atomistic protein generation through multi-modal flow matching"

- Latent space: A learned continuous representation capturing sequence and side-chain details for generative modeling. "via a continuous latent space"

- Local coordinate frame: A residue-centric coordinate system used to model atomic positions relative to backbone geometry. "constructs a residue-centric local coordinate frame "

- Multi-modal generation: Joint generation over multiple dependent data modalities (sequence, backbone, side-chain atoms). "We treat this as a joint multi-modal generation task"

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): A set of homologous sequences aligned to reveal evolutionary constraints for folding. "multiple sequence alignments (MSAs)"

- Non- atoms: All backbone and side-chain atoms other than Cα, encoding local residue-specific details. "non- backbone and side-chain atoms represent local details."

- Non-equivariant architecture: A model that does not enforce geometric equivariance (e.g., SE(3)) but uses learned biases. "a high-capacity, non-equivariant architecture"

- Novelty: A metric quantifying how dissimilar generated structures are from known databases (e.g., PDB/AFDB). "achieving competitive novelty scores"

- Pallatom: An all-atom generative method using Atom14 that may suffer atom-type ambiguities. "Pallatom's~\citep{qu2024pallatom} use of Atom14 representations"

- Pareto frontier: The curve showing optimal trade-offs (e.g., between co-designability and diversity). "Pareto frontier of the co-designability-diversity trade-off"

- pLDDT: A per-residue confidence score output by AlphaFold-like models indicating prediction reliability. "with a filter of pLDDT 0.8."

- ProteinMPNN: An inverse-folding model that predicts sequences for target backbones with strong experimental support. "We leverage ProteinMPNN"

- Protpardelle: An early all-atom diffusion-based generative method reported to have poor results in practice. "Early all-atom diffusion attempts like Protpardelle~\citep{chu2024protpardelle} yield poor results."

- Push-forward: The operation transporting a distribution through a mapping in flow-based generative modeling. "where “” denotes push-forward"

- Residue: An individual amino acid unit within a protein chain. "Each residue does not possess all 36 possible non- atoms"

- RMSD: Root mean square deviation measuring structural distance between two conformations. "Histograms of and all-atom RMSD"

- Rotamer: A discrete conformational state of a side chain used in packing or reconstruction. "packing side-chains using rotamers"

- scRMSD: Side-chain RMSD, quantifying deviations in side-chain atom positions between structures. "using all-atom scRMSD."

- Side-chain initialization: A strategy to set initial coordinates for side-chain atoms when residue types become unmasked during generation. "for side-chain initialization, there is no noisy input available"

- Triangle update layers: Specialized geometric relational layers used in some structure models (e.g., AlphaFold), omitted here. "do not use any triangle update layers."

- Vector field: The learned velocity function driving the ODE that transports noise to data in flow models. "defined through a learnable vector field "

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by leveraging the paper’s newly released aligned synthetic sequence–structure dataset (D) and the two generative models (La-Proteina for explicit multi-modal flow matching, and the partially latent La-Proteina model referred to as “i”), along with established folding and downstream analysis tools.

- Atomistic de novo protein co-design pipelines that eliminate post-hoc redesign

- Sector: healthcare, biotech, diagnostics, industrial enzymes

- Action: Replace backbone-only generation + ProteinMPNN redesign with direct sequence-and-side-chain generation using La-Proteina or i, followed by in silico folding checks (ESMFold/AF2) and developability screens prior to synthesis.

- Tools/workflow: La-Proteina or i → co-designability filtering (CODES-AA via ESMFold/AF2) → energy/refinement (Rosetta, MD) → expression and biophysical assays.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Co-designability and pLDDT thresholds correlate with experimental foldability; access to wet-lab validation; careful screening for stability, aggregation, and immunogenicity.

- High-throughput libraries of structurally diverse, co-designable proteins for screening

- Sector: biopharma discovery, synthetic biology, materials

- Action: Use low-temperature sampling to steer the diversity–designability Pareto frontier (as demonstrated) and generate libraries spanning 100–400 residues that are co-foldable without redesign.

- Tools/workflow: Batch generation with La-Proteina or i → clustering and novelty checks (Foldseek, AFDB/PDB comparisons) → function prediction/docking → experimental down-selection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Compute resources for large-batch generation; downstream function prediction is an open problem; novelty metrics avoid trivial PDB-like recapitulation.

- Structure-guided side-chain design for contact geometry and motif scaffolding (atomistic granularity)

- Sector: binder design (protein–protein), enzyme active-site placements, biosensors

- Action: Exploit explicit Atom37 modeling and side-chain initialization to place interaction-critical residues and local geometry, enabling more accurate scaffolds than backbone-only models.

- Tools/workflow: Conditional generation around motifs/frames → binding assessment (Boltz-1, AF3-style interaction prediction, docking) → iterative refinement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Motif-conditional generation may require fine-tuning; interaction predictors for true binding affinity remain imperfect; wet-lab validation needed.

- Dataset curation and benchmarking standards for co-designability

- Sector: academia, software tooling, policy

- Action: Adopt D as a training/finetuning resource to improve joint modeling; incorporate Cα and all-atom RMSD, pLDDT thresholds, and mask-aware side-chain handling as standard dataset quality checks.

- Tools/workflow: Data loaders and filters using ESMFold/AF2; standardized co-designability metrics (CODES, CODES-AA); public benchmarks for backbone + side-chain modeling.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community alignment on cutoffs (e.g., 2 Å RMSD); consistent licensing and access to D; reproducibility across folding models.

- Educational and research use for studying sequence–structure coupling

- Sector: academia, education

- Action: Use the aligned dataset and both models to teach/practice joint discrete–continuous generation, latent-vs-explicit modeling, and multi-modal flow matching.

- Tools/workflow: Course modules, hands-on labs with D + La-Proteina/i; ablation studies on masking schedules, local frames, Atom37 vs Atom14.

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPU availability for small-scale training/inference; instructor familiarity with protein ML tooling.

- Practical guidance for safer model deployment and funding reviews

- Sector: policy, research governance

- Action: Require co-designability checks and wet-lab gating before dissemination; mandate novelty and risk screening for designed sequences prior to synthesis.

- Tools/workflow: Pre-synthesis compliance checklist (CODES-AA, novelty vs PDB/AFDB, hazard scans), institutional biosafety review.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Institutional policies for dual-use risk; adoption of standardized screening; integration with synthesis provider safeguards.

Long-Term Applications

These applications are promising but require further research, scaling, conditional modeling, integration with functional assays, and/or regulatory frameworks.

- Therapeutic protein design with developability-aware objectives

- Sector: healthcare, pharma

- Product/workflow: “Atomistic Co-Design Studio” that jointly optimizes structure, sequence, stability, solubility, immunogenicity, and manufacturability; integrates co-design generation, biophysical predictors, and closed-loop wet-lab data.

- Dependencies: Robust function prediction; multi-objective optimization; clinical safety/tox profiles; scalable expression systems; regulatory compliance.

- Generalizable motif scaffolding and binder design against arbitrary epitopes

- Sector: biotech, vaccines, diagnostics

- Product/workflow: Conditional generative models that accept user-specified active-site geometries or target epitopes and produce atomistic scaffolds with high binding propensity.

- Dependencies: Accurate epitope mapping; improved interaction predictors; cofactor/ligand modeling; experimental HVAs (high-throughput validation assays).

- Industrial biocatalysts for green chemistry and manufacturing

- Sector: energy, materials, consumer goods, agriculture

- Product/workflow: De novo enzymes tailored to harsh process conditions (pH, temperature, solvents) for carbon capture, plastic depolymerization, biofuel synthesis, food/textile processing.

- Dependencies: Functional optimization beyond fold; process stability; scale-up bioreactors; IP and safety reviews; lifecycle and environmental impact assessments.

- Advanced biosensors and point-of-care diagnostics

- Sector: healthcare, environmental monitoring, consumer health

- Product/workflow: De novo proteins with engineered allosteric sites or transduction interfaces for sensitive detection of metabolites, pathogens, and environmental toxins.

- Dependencies: Specificity/affinity engineering; integration with devices; ruggedness; regulatory approvals for clinical use.

- Bio-based materials and structural protein engineering

- Sector: materials science, sustainability

- Product/workflow: High-strength, self-assembling proteins for adhesives, fibers, and coatings; programmable interfaces for hierarchical assembly.

- Dependencies: Predictive models for multi-protein assemblies; long-length atomistic co-design; mechanical property testing; scalable manufacturing.

- Synthetic biology circuits and living therapeutics

- Sector: synthetic biology, therapeutics

- Product/workflow: Proteins designed as logic gates, sensors, and effectors in engineered cells and microbiomes; de novo effectors for targeted therapy (e.g., microbiome modulation).

- Dependencies: Robust expression control; host compatibility; safety/containment; regulatory and ethical oversight.

- Standards and governance for generative protein technologies

- Sector: policy, research governance

- Product/workflow: International standards for dataset consistency (co-designability, pLDDT), risk assessment pipelines, and red-teaming methodologies for protein generators.

- Dependencies: Community consensus; cross-agency coordination; synthesis provider alignment; sustained funding.

Cross-Cutting Assumptions and Dependencies

- In silico metrics vs. wet-lab reality: Structural co-designability (RMSD, pLDDT) is necessary but not sufficient for functional success; experimental validation remains essential.

- Model generalization: Current strengths are on soluble, single-chain proteins in the studied length range; multi-domain, membrane proteins, and ligand/cofactor-bound states need targeted modeling.

- Compute and data access: Training and inference require GPUs and robust data loaders; widespread adoption benefits from open-source releases and cloud-hosted services.

- Safety and ethics: Dual-use risks (e.g., unintended toxicity) necessitate screening and governance; institutional biosafety and synthesis provider checks should be integrated.

- IP/licensing: Dataset and model licenses determine commercial reuse; proprietary or restricted data may limit deployment.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.