Revisiting Generalization Across Difficulty Levels: It's Not So Easy (2511.21692v1)

Abstract: We investigate how well LLMs generalize across different task difficulties, a key question for effective data curation and evaluation. Existing research is mixed regarding whether training on easier or harder data leads to better results, and whether those gains come on easier or harder test data. We address this question by conducting a systematic evaluation of LLMs' generalization across models, datasets, and fine-grained groups of example difficulty. We rank examples in six datasets using the outputs of thousands of different LLMs and Item Response Theory (IRT), a well-established difficulty metric in educational testing. Unlike prior work, our difficulty ratings are therefore determined solely by the abilities of many different LLMs, excluding human opinions of difficulty. With a more objective, larger-scale, and finer-grained analysis, we show that cross-difficulty generalization is often limited; training on either easy or hard data cannot achieve consistent improvements across the full range of difficulties. These results show the importance of having a range of difficulties in both training and evaluation data for LLMs, and that taking shortcuts with respect to difficulty is risky.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper studies a simple question: if you train a LLM mostly on easy problems, will it get better at hard ones—and if you train on hard problems, will it get better at easy ones? The authors call this “cross-difficulty generalization.” They find that this kind of generalization is much weaker than many people expect. To get reliable performance, models need practice on a range of difficulties, not just easy or just hard examples.

Key Questions

The paper focuses on three main questions:

- Can models trained on easy tasks perform well on hard tasks?

- Can models trained on hard tasks perform well on easy tasks?

- How does the “gap” between the difficulty of training data and test data affect performance?

How They Did It (Methods)

Think of this like a big school exam:

- The “students” are many different LLMs.

- The “questions” come from six well-known datasets (like math problems or science questions).

- The goal is to figure out which questions are easy or hard for models—not for humans.

To measure difficulty, the authors use a tool called Item Response Theory (IRT):

- IRT is used in real-life testing (like SAT or GRE) to estimate two things at the same time:

- How difficult each question is.

- How capable each student is.

- In this paper, models are the “students,” and questions are the “items.”

- If lots of models get a question wrong, it’s probably “hard” for models. If many get it right, it’s “easy.”

Instead of asking humans what’s hard or easy (like “this is 8th-grade level”), they:

- Collected results from thousands of models on public leaderboards.

- Used IRT to compute a difficulty score for every question based on model performance.

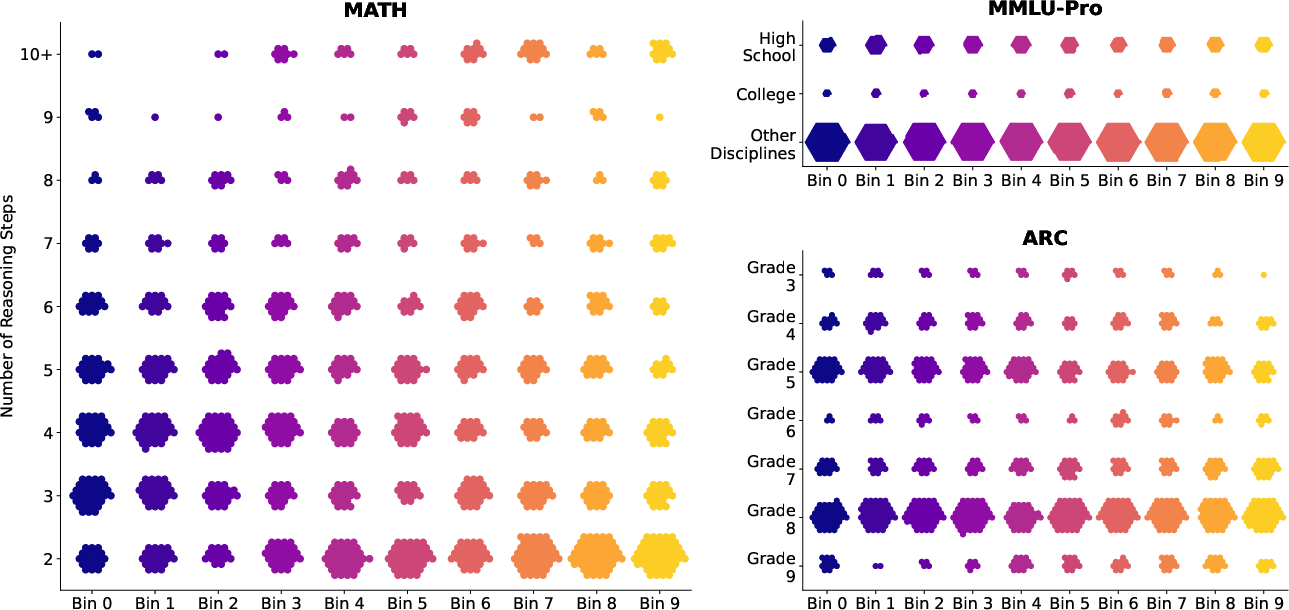

- Sorted each dataset’s questions into 10 “bins,” from easiest (bin 0) to hardest (bin 9).

Then they ran experiments:

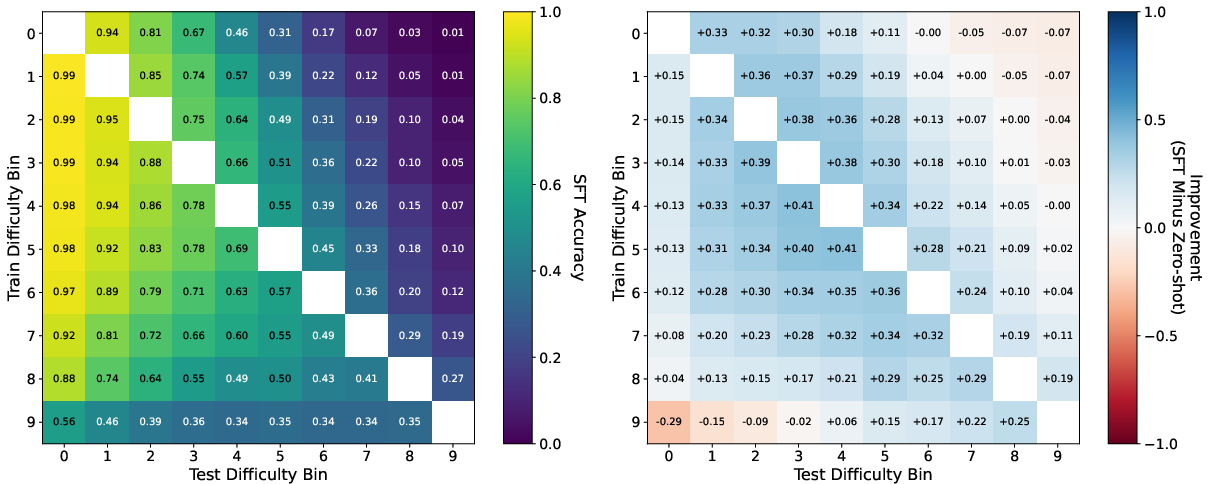

- Train a model only on one bin (say, bin 2).

- Test the model on all other bins (bins 0–9).

- Compare results to the model’s “zero-shot” performance (its score without extra training).

- Repeat across multiple models and datasets.

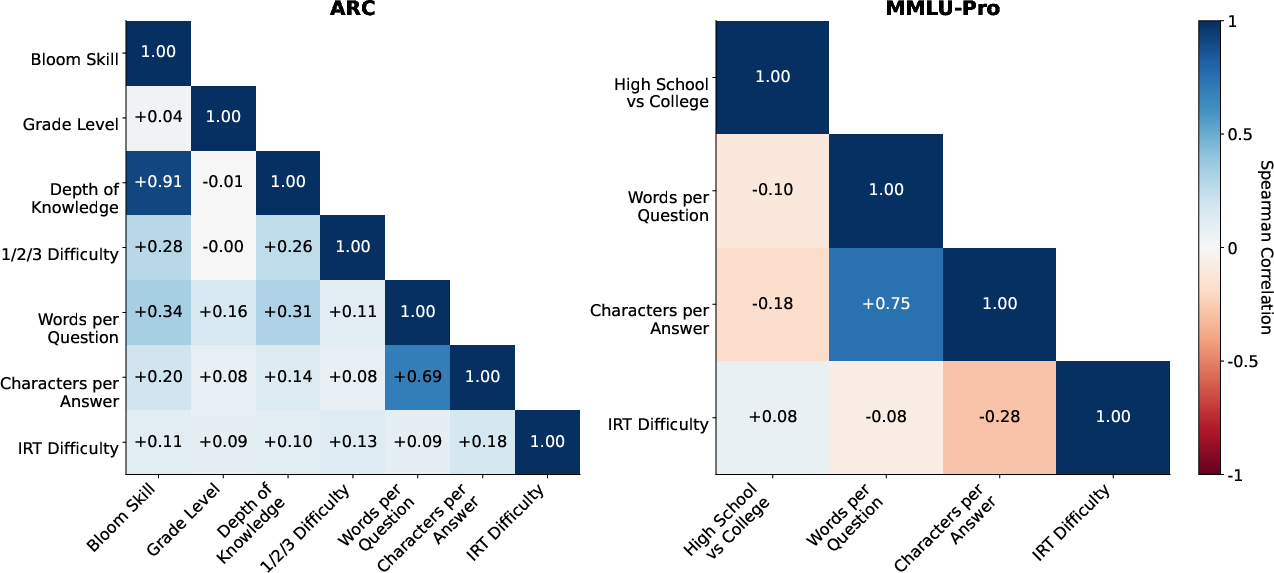

They also compared IRT difficulty to human-style difficulty labels (like grade level or number of steps) and checked if those matched.

Main Findings

Here are the most important results:

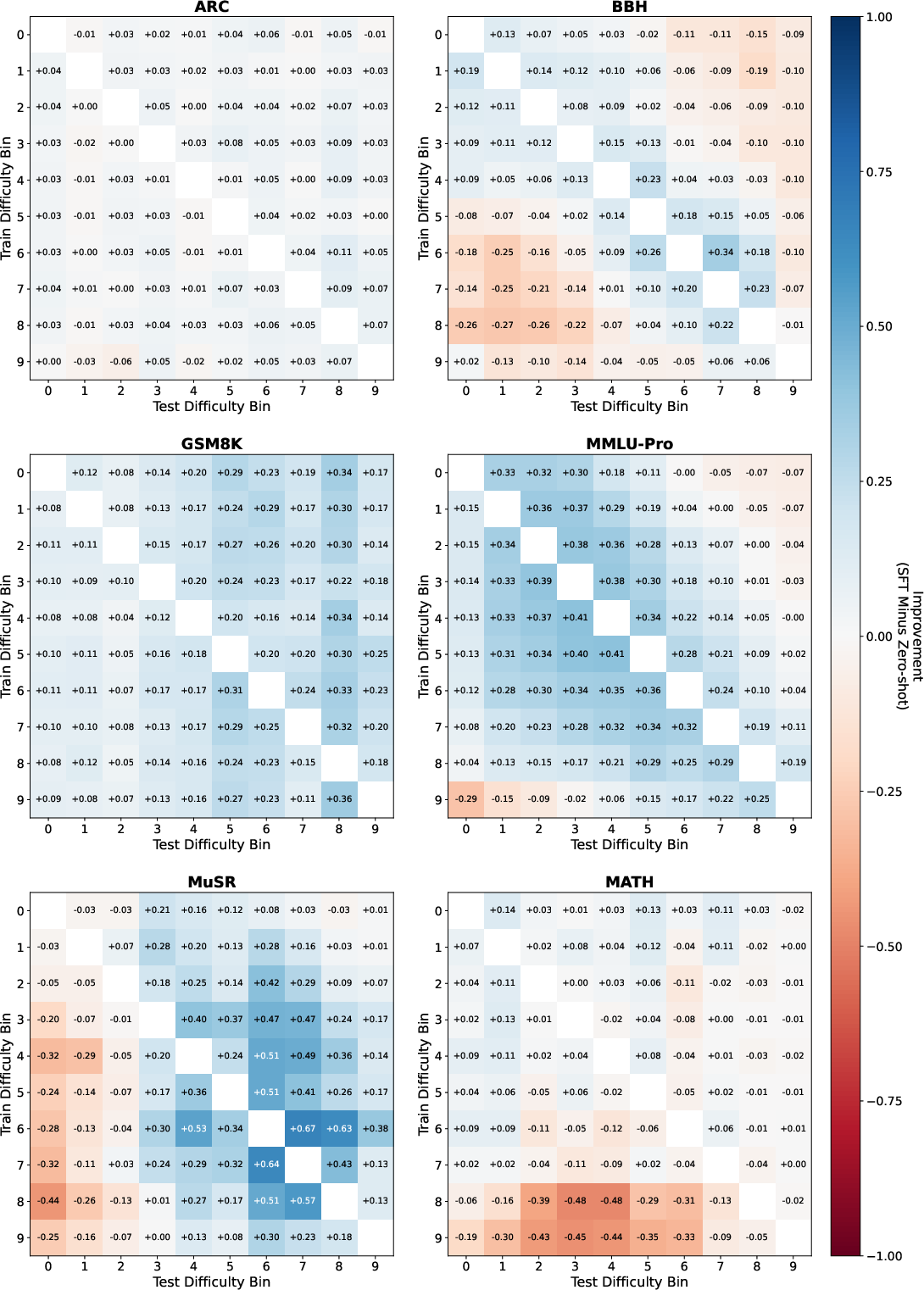

- Training only on easy data does not reliably help on hard data. Gains fade quickly as test questions get harder.

- Training only on hard data does not reliably help on easy data. In some cases, performance even gets worse on the easy questions.

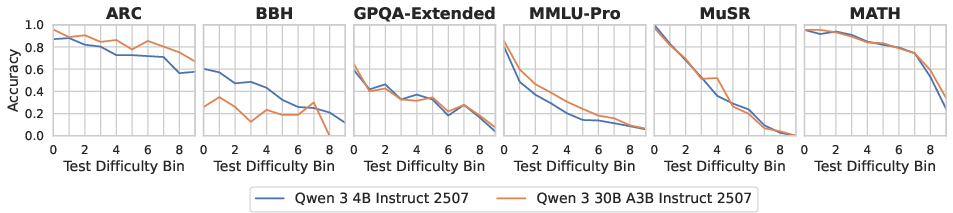

- The best generalization happens between neighboring difficulty levels. If you train on bin 3, you do best on bins 2–4. As the difficulty gap grows (like training on bin 1 and testing on bin 8), performance drops and can go below the model’s zero-shot score.

- Human-based difficulty labels (like grade level, question length, or expert “easy/medium/hard”) often do not match what is hard for models. A question that’s easy for people can be hard for models, and vice versa.

- These patterns show up across different model families (Qwen and Llama), sizes (from small to larger), and datasets (reasoning, math, science, etc.), suggesting the effect is general, not a quirk of one model or task.

Why This Matters

This research has practical consequences:

- If you only train on easy problems and hope the model will magically get good at hard ones, that’s risky. The same is true if you only train on hard problems.

- To build stronger, more reliable models, training data should include a mix of difficulties. This helps models learn skills that transfer across levels.

- For fair evaluation, test sets should include both easy and hard questions. A model that aces hard tests may still struggle with easy ones—and you won’t know unless you check.

- Difficulty measured by human intuition (like “this is high school level”) doesn’t always reflect what’s challenging for models. Using model-based difficulty (like IRT) can help design better training curricula and benchmarks.

In short: models don’t automatically “bridge the difficulty gap.” To make them truly robust, we need difficulty-aware training and testing that cover the full spectrum from easy to hard.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved Knowledge Gaps, Limitations, and Open Questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, aimed to guide future research:

- Difficulty modeling assumptions:

- Evaluate whether conclusions hold under richer IRT models (2PL/3PL) and multidimensional IRT (MIRT), which relax Rasch’s equal-discrimination, no-guessing, and unidimensional ability assumptions.

- Investigate partial-credit or ordinal-scoring IRT for generative tasks where “binary correct” undercounts near-miss answers.

- Stability and invariance of difficulty estimates:

- Test how IRT-based difficulty changes as the pool of models evolves (e.g., frontier or more capable future models), and whether bins must be periodically recalibrated.

- Quantify the invariance of IRT difficulty across model families and training paradigms (SFT vs RLHF vs tool-using models), beyond the limited validation with Qwen.

- Assess sensitivity to the number of bins and binning thresholds (e.g., 5 vs 10 vs 20 bins) and whether core conclusions change.

- Data and evaluation artifacts:

- Audit heterogeneity in leaderboard results used for IRT (prompt templates, decoding, seeds, CoT vs non-CoT, self-consistency, tool use); quantify how such differences bias difficulty estimates.

- Address near-duplicate or closely related models on the leaderboard (family clusters), which may inflate some items’ difficulty or ability estimates; explore model de-duplication or family-weighted IRT.

- Verify that scoring pipelines (exact match vs heuristic matching) do not systematically distort item difficulty across datasets.

- Scope of tasks and modalities:

- Extend analysis beyond English QA/math reasoning to coding, multimodal, instruction-following with subjective judgments, and open-ended generation to see if cross-difficulty patterns persist.

- Separate multiple-choice vs free-form generation tasks to assess whether cross-difficulty generalization differs by response format.

- Confounding factors in bin composition:

- Control for topical/domain distribution within bins to distinguish difficulty effects from domain shift; conduct within-domain binning and analyze subcategories separately.

- Examine length and format shifts across bins (e.g., reasoning chain length, answer length) to determine if training on one distribution degrades performance on different-length distributions.

- Training methodology coverage:

- Compare SFT with alternative training regimes (RLHF, DPO, reward modeling, GRPO, tool-augmented training) to evaluate whether the limited cross-difficulty generalization is method-specific.

- Study curriculum learning and mixture-of-bins training (e.g., easy→hard, anti-curriculum, adaptive sampling by IRT scores) rather than single-bin SFT.

- Analyze the effect of training budget and hyperparameters (epochs, LR, regularization, parameter-efficient tuning vs full fine-tuning) on cross-difficulty transfer.

- Explore training with rationales (CoT) or step-by-step supervision on easy bins as a mechanism for easy-to-hard generalization.

- Test-time strategies:

- Evaluate whether test-time compute (self-consistency, majority voting), prompting strategies (few-shot, CoT prompting), or tool use (retrieval, calculators) alter cross-difficulty generalization.

- Metrics and statistical rigor:

- Go beyond accuracy to measure calibration, consistency, and robustness across bins; determine whether generalization failures are accuracy-only or broader.

- Report statistical significance and variability across random seeds and runs; quantify reliability of observed heatmap patterns.

- Data quantity vs difficulty:

- Disentangle effects of training set size from difficulty by equalizing token budgets across conditions and measuring sample-efficiency trade-offs.

- Investigate whether sparse training on targeted hard or easy exemplars with high “discrimination” (in IRT sense) yields better cross-bin gains than uniform bin sampling.

- Theoretical understanding:

- Develop theory linking difficulty gaps to generalization properties of LLMs (e.g., distribution shift, hypothesis class capacity, length/complexity extrapolation).

- Identify the latent factors (skills, sub-capabilities) most predictive of IRT difficulty and model where transfer does or doesn’t occur across those factors.

- Robustness to contamination and leakage:

- Re-evaluate findings on genuinely unseen, post-cutoff test sets to rule out inflation from pretraining overlap, especially given leaderboard-based signals.

- Multilingual and cross-cultural generalization:

- Replicate the analysis in non-English and multilingual settings to determine whether limited cross-difficulty generalization is language- or culture-specific.

- Practical evaluation design:

- Provide actionable guidelines on difficulty-aware benchmark construction (e.g., recommended difficulty mixture proportions) and quantify how evaluation conclusions change with difficulty composition.

Glossary

- Bloom’s taxonomy: A hierarchical framework that classifies cognitive skills from basic recall to complex reasoning. "based on Bloom's taxonomy~\citep{bloom1956taxonomy}, Depth of Knowledge~\citep{webb2002dok}, and 1/2/3 expert difficulty ratings."

- Depth of Knowledge (DOK): A framework categorizing the complexity of cognitive processes required to answer a question. "The Depth of Knowledge metric classifies questions by the cognitive process depth needed to arrive at an answer, ranging from Level 1 (Recall and Reproduction) to Level 4 (Extended Thinking)~\citep{webb2002dok}."

- GRPO: A reinforcement learning optimization method used to train models by maximizing relative rewards. "showed training on the hardest examples using GRPO~\citep{shao2024grpo} consistently outperforms using all data."

- In-context learning (ICL): A capability where models learn from examples provided in the prompt without updating parameters. "SFT, ICL, \ Linear Probing"

- Item Response Theory (IRT): A psychometric framework modeling the probability of a correct response as a function of item difficulty and subject ability. "We rank examples in six datasets using the outputs of thousands of different LLMs and Item Response Theory (IRT), a well-established difficulty metric in educational testing."

- Linear probing: Training a simple linear classifier head on frozen representations to assess learned features. "SFT, ICL, \ Linear Probing"

- Open LLM Leaderboard: A public platform that aggregates benchmark evaluations for many open-source LLMs. "from the Open LLM Leaderboard~\citep{open-LLM-leaderboard-v1, open-LLM-leaderboard-v2}, a popular hub in the community for benchmark results."

- Perplexity: A language modeling metric indicating uncertainty, defined as the exponentiated average negative log-likelihood. "such as perplexity, confidence, success rate, and loss~\citep{swayamdipta2020dataset, hase2024unreasonable, pikus2025hardexamplesneedmaximizing}."

- Pointwise V-information (PVI): An information-theoretic measure of how informative an individual datapoint is for a given model class. "propose an information-theoretic approach using V-usable information and pointwise V-information (PVI) to measure question difficulty for a particular model."

- Rasch (1PL) model: The one-parameter logistic IRT model that uses item difficulty and subject ability to predict correctness. "In particular, we use the Rasch (1PL) model~\citep{rasch1960probabilistic} to determine the example's difficulty."

- Reinforcement learning (RL): A training paradigm where models learn policies to maximize cumulative rewards. "RL"

- Reward model: A learned model that estimates the quality or reward of outputs, often used to guide RL or alignment. "reward models can."

- Spearman rank correlation coefficient: A nonparametric statistic measuring the monotonic relationship between ranked variables. "We quantify this relationship by calculating the Spearman rank correlation coefficient between each pair of difficulty metrics."

- Stochastic variational inference (SVI): A scalable approximate Bayesian inference method using stochastic optimization of variational objectives. "We estimate posterior distributions over the latent parameters of the 1PL model using stochastic variational inference and take their expected values as point estimates."

- Supervised fine-tuning (SFT): Further training a pretrained model on labeled data to improve task performance. "We train the LLMs using supervised fine-tuning exclusively on a single difficulty bin and repeat this process for all bins in the dataset."

- V-usable information: An information-theoretic quantity measuring how useful data is for a particular model class. "propose an information-theoretic approach using V-usable information and pointwise V-information (PVI) to measure question difficulty for a particular model."

- Zero-shot: Evaluation or performance on a task without any task-specific training or fine-tuning. "to isolate the effect of cross-difficulty generalization over the zero-shot baseline"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following items outline concrete use cases that can be deployed now, leveraging the paper’s model-based difficulty estimation (IRT), findings about limited cross-difficulty generalization, and evaluation workflows.

- Difficulty-aware data curation pipeline for LLM training

- Sectors: software, AI tooling, data ops

- What: Integrate IRT scoring into data pipelines to bin training examples by model-centric difficulty and ensure a targeted mixture of difficulties rather than relying solely on “easy” or “hard” subsets.

- Tools/products/workflows:

py-irt+ scraped/collected model responses; difficulty-bin stratification; automated sampling policies (balanced or adjacent-bin-focused). - Assumptions/dependencies: Requires sufficient model-response coverage to fit IRT; binary/categorical correctness signals; difficulty scores will shift as model families evolve.

- Cross-difficulty audit dashboards for model evaluations

- Sectors: software (ML platform teams), academia (evaluation), policy (audits)

- What: Produce heatmaps (as in the paper) that compare training-bin vs test-bin accuracy deltas to diagnose overfitting to specific difficulty ranges and quantify the “difficulty gap” penalty.

- Tools/products/workflows:

lm-eval-harness, Open LLM Leaderboard-derived evaluations, visualization modules. - Assumptions/dependencies: Benchmark tasks must have reliable ground truth; evaluations should be stratified into difficulty bins; English-centric datasets if using the paper’s bins.

- Benchmark design and procurement guidelines emphasizing difficulty diversity

- Sectors: academia (benchmark creation), policy (standards), software (MLOps)

- What: Redesign and annotate benchmarks to include a broad spectrum of model-based difficulties rather than human-grade labels alone.

- Tools/products/workflows: Difficulty-binned splits; reporting templates that include “difficulty coverage” metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to multi-model evaluation logs to estimate IRT difficulty; willingness to evolve legacy benchmark taxonomies.

- Training budget allocation rules based on target difficulty windows

- Sectors: software (LLM teams), finance (ROI analysis for ML)

- What: Match training spend to the difficulty ranges that align with product goals (e.g., customer support copilot focuses on mid-bin generalization).

- Tools/products/workflows: Bin-level ROI tracking; adjacent-bin fine-tuning rather than extremes; curriculum tuning by difficulty.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Product KPIs can be mapped to difficulty bands; bin-level performance metrics available.

- Difficulty-aware model routing and fallback strategies in production

- Sectors: software (platforms), customer support, education

- What: Estimate input difficulty and route requests to models specialized for that range; escalate to human or more capable models for out-of-range difficulties.

- Tools/products/workflows: Lightweight difficulty classifiers trained on IRT-binned data; routing policies; human-in-the-loop escalation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Feasible difficulty estimation from input features or quick probe inference; cost-aware routing; clear SLAs.

- Capability statements and documentation that reflect difficulty coverage

- Sectors: policy (compliance), software (product/docs), healthcare/finance (regulated domains)

- What: Replace generic performance claims with bin-stratified capability disclosures (e.g., “strong in bins 2–5; weak above bin 7”).

- Tools/products/workflows: Reporting templates; bin-wise accuracy summaries; customer guidance for expected failure modes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stakeholder acceptance of difficulty-centric reporting; periodic revalidation as models drift.

- Adjacent-bin training practices to maximize generalization

- Sectors: software (ML training), education (tutoring models)

- What: Prefer fine-tuning on bins near the target difficulty to avoid performance cliff effects suggested by large train–test difficulty gaps.

- Tools/products/workflows: Curriculum sampling; validation on neighboring bins; guardrails to prevent extreme bin-only training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate mapping of product use-cases to target difficulty; sufficient data per bin.

- Data acquisition prioritization to fill difficulty gaps

- Sectors: data marketplaces, enterprise data teams

- What: Identify bins where models underperform and acquire/label more data in those bands rather than indiscriminately collecting “hard” or “easy” samples.

- Tools/products/workflows: Gap analysis via bin-wise deltas; targeted dataset requests; active learning tuned to difficulty bands.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable bin-wise performance signals; consistent annotation quality.

- Classroom and tutoring systems that adapt content difficulty using model-centric scores

- Sectors: education

- What: Use IRT-binned questions to control lesson difficulty and avoid over-reliance on human grade levels that poorly correlate with LLM difficulty.

- Tools/products/workflows: Adaptive practice engines; diagnostic tests using IRT-based bins; feedback loops to adjust difficulty in real time.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Alignment between learner needs and LLM difficulty (distinct from human difficulty); careful validation to avoid mis-calibration.

- User-facing guidance for daily use of assistants

- Sectors: daily life, productivity software

- What: Provide tips to users on task framing and expectations (e.g., more complex multi-step prompts may fall into higher bins; prepare to escalate or break tasks down).

- Tools/products/workflows: Inline UX hints; suggest decomposition workflows for high-difficulty tasks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ability to estimate task difficulty from prompt structure; effective prompt decomposition strategies.

- Compliance and risk teams’ checklists for difficulty-aware testing

- Sectors: finance, healthcare, legal/compliance

- What: Test models across a range of model-based difficulty bins for domain-specific tasks before deployment; document weaknesses and escalation protocols.

- Tools/products/workflows: Bin-wise test suites for clinical coding, claims adjudication, or legal research; failure mode cataloging.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain datasets can be binned via IRT; rigorous ground truth and supervision are available.

Long-Term Applications

The following items require further research, scaling, or development (e.g., multilingual extension, new training objectives, regulatory adoption).

- Standardized difficulty-aware evaluation protocols and certifications

- Sectors: policy, standards bodies, academia

- What: Formalize IRT-based difficulty reporting into industry standards for LLM evaluations; include “difficulty coverage” in certifications.

- Tools/products/workflows: Benchmark governance; third-party audits; reference implementations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Broad consensus on model-centric difficulty; accessible multi-model evaluation infrastructure.

- Difficulty-aware curriculum learning and dynamic training schedulers

- Sectors: software (ML training), research

- What: Develop training algorithms that automatically select and mix bins to stabilize generalization across difficulty; optimize for smooth performance curves rather than top-line accuracy.

- Tools/products/workflows: Difficulty-conditioned sampling; RLHF/GRPO variants with difficulty regularization; 2PL/3PL IRT integration (discrimination/guessing).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scalable training infrastructure; robust difficulty labels during training; evidence that curriculum improves generalization.

- Difficulty-aware multi-model routing and orchestration across tools

- Sectors: software (platform tooling), robotics/workflow automation

- What: Create orchestrators that assess task difficulty and route to appropriate toolchains (e.g., code synthesis model for mid bins; formal verifier plus human for high bins).

- Tools/products/workflows: Difficulty estimators; orchestration engines; cost–quality optimization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate difficulty prediction pre-inference; well-defined tool–bin affinity.

- Difficulty-centric risk modeling for deployment and SLAs

- Sectors: finance, healthcare, enterprise IT

- What: Predict failure rates per difficulty bin to set SLAs, fallback policies, and liability thresholds; allocate human review for higher bins.

- Tools/products/workflows: Reliability curves per bin; stochastic risk models; SLA templates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Historical data linking bin difficulty to failure modes; regulatory acceptance.

- Multilingual and cross-domain extensions of model-based difficulty estimation

- Sectors: global software, public sector, education

- What: Extend IRT-based difficulty scoring beyond English and across specialized domains (e.g., clinical notes, legal contracts).

- Tools/products/workflows: Multilingual benchmarks with binning; domain-specific ground truths; multi-model evaluation hubs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Diverse model responses in non-English; domain labels with high fidelity; cross-cultural variability in “difficulty.”

- Public benchmark marketplaces annotated with model-centric difficulty

- Sectors: software (data marketplaces), academia

- What: Offer datasets with precomputed difficulty bins and metadata, enabling teams to purchase targeted gaps (e.g., “bins 6–8 for scientific reasoning”).

- Tools/products/workflows: Data catalogs; difficulty metadata APIs; vendor-neutral curation criteria.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sustainable economics of data-sharing; privacy and licensing constraints.

- Adaptive tutoring and assessment systems co-calibrated for human and LLM difficulty

- Sectors: education

- What: Align human difficulty (grade level, cognitive skill) with model-centric difficulty to design fair exams and robust AI tutors that do not overfit to LLM strengths.

- Tools/products/workflows: Dual-scale calibrations; psychometrics integrating human + model signals; assessment authoring tools.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Research to reconcile divergences between human and model difficulty; educator buy-in.

- Product-level “difficulty coverage” KPIs and procurement standards

- Sectors: enterprise software, procurement, policy

- What: Introduce KPIs that require coverage across difficulty bins for any procured AI solution to prevent narrow generalization.

- Tools/products/workflows: RFP templates; vendor scorecards; periodic coverage audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational maturity to adopt nuanced KPIs; vendor transparency.

- Generative data synthesis targeted at difficulty gaps

- Sectors: software (ML training), academia

- What: Use controllable generation to synthesize examples specifically within underperforming bins; validate via multi-model IRT scoring.

- Tools/products/workflows: Difficulty-conditioned data generation; adversarial augmentation; synthetic-to-real validation pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable control over generated difficulty; avoidance of label noise and leakage.

- Difficulty-aware safety and alignment evaluations

- Sectors: policy, safety research

- What: Construct adversarial and safety benchmarks stratified by model-centric difficulty to evaluate robustness and alignment under increasing task complexity.

- Tools/products/workflows: Safety suites with bins; red-teaming scaled by difficulty; reporting of failure patterns across bins.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Well-defined safety ground truths; cooperation across labs and regulators.

- Improved difficulty models beyond 1PL (e.g., 2PL/3PL with discrimination and guessing)

- Sectors: academia, software (evaluation tooling)

- What: Capture item discrimination (how sharply a question separates model abilities) and guessing to refine difficulty estimation and training selection.

- Tools/products/workflows: Enhanced IRT implementations; parameter estimation pipelines; comparative studies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sufficient evaluation breadth to fit richer models; interpretability standards.

- Consumer-facing assistants with difficulty-aware guidance and escalation

- Sectors: daily life, productivity apps

- What: Assistants that detect likely high-difficulty tasks (multi-step reasoning, ambiguous inputs) and proactively recommend decomposition, verification, or human help.

- Tools/products/workflows: UX cues; “break down into steps” suggestions; auto-verification flows for high bins.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Acceptable latency for difficulty detection; user trust and adoption.

These applications rely on the paper’s core insights: (1) difficulty is model-centric and poorly captured by human labels; (2) generalization degrades as train–test difficulty diverges; and (3) training and evaluation should mix difficulty levels rather than prioritize extremes. Adopting difficulty-aware practices can improve reliability, transparency, and real-world performance across sectors.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.