Some aspects of robustness in modern Markov Chain Monte Carlo

Abstract: Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) is a flexible approach to approximate sampling from intractable probability distributions, with a rich theoretical foundation and comprising a wealth of exemplar algorithms. While the qualitative correctness of MCMC algorithms is often easy to ensure, their practical efficiency is contingent on the target' distribution being reasonably well-behaved. In this work, we concern ourself with the scenario in which this good behaviour is called into question, reviewing an emerging line of work onrobust' MCMC algorithms which can perform acceptably even in the face of certain pathologies. We focus on two particular pathologies which, while simple, can already have dramatic effects on standard `local' algorithms. The first is roughness, whereby the target distribution varies so rapidly that the numerical stability of the algorithm is tenuous. The second is flatness, whereby the landscape of the target distribution is instead so barren and uninformative that one becomes lost in uninteresting parts of the state space. In each case, we formulate the pathology in concrete terms, review a range of proposed algorithmic remedies to the pathology, and outline promising directions for future research.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

A simple explanation of “Some aspects of robustness in modern Markov Chain Monte Carlo”

1. What is this paper about?

This paper looks at how to make a popular sampling method, called Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), work reliably even when the problem is “difficult.” MCMC is used to draw random samples from complicated probability distributions (think of shapes or landscapes that tell us which values are likely). The authors focus on making MCMC robust—meaning it still works well—even when the target distribution is rough or flat in ways that usually break standard methods.

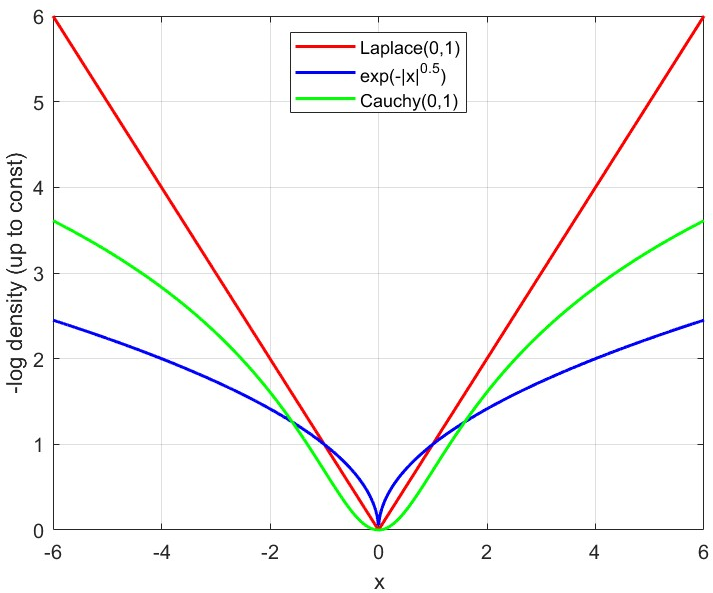

- Roughness: the landscape changes abruptly or has sharp corners, so following the slope can be unstable.

- Flatness (also called heavy-tailedness): the landscape is very spread out, so the sampler wanders and gets lost far from interesting areas.

2. What questions are the authors asking?

The paper asks:

- Which standard MCMC methods work well when the target distribution is smooth and well-behaved?

- What goes wrong when the distribution is rough or flat/heavy-tailed?

- Which newer or modified MCMC methods handle these problems more robustly?

- How should we think about designing MCMC so it still performs decently in tough situations?

3. How do they approach the problem?

This is a review paper: it explains, compares, and demonstrates different MCMC strategies rather than proposing one new algorithm. It also shows small experiments to illustrate key points.

To make the ideas intuitive, think of sampling as hiking on a landscape:

- The landscape is the “log-density” of the target distribution. Hills and valleys represent where points are more or less likely.

- A “gradient” is the local slope telling you which direction goes uphill or downhill.

- A “step-size” is how big a stride you take each move.

- “Acceptance probability” is like a gatekeeper: even if you propose a step, you might be told “no” if it looks unlikely under the target.

The paper explains four major families of MCMC methods:

- Random Walk Metropolis and Metropolis-Hastings: you propose a move (like a blind step) and accept/reject it to exactly target the right distribution.

- Langevin-based methods (ULA and MALA): you use the slope of the landscape (the gradient) plus randomness to propose smarter moves. ULA is an approximate method; MALA adds an accept/reject step to remove bias.

- Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) and Refreshed Hamiltonian Dynamics (RHMC): you add “momentum” so you glide across the landscape more smoothly and explore faster. Think of rolling a ball instead of just stepping.

- Piecewise-Deterministic Markov Processes (PDMPs), like the Bouncy Particle Sampler (BPS) and Zig-Zag Process (ZZS): you move with constant speed and occasionally “bounce” or flip direction, guided by the shape of the landscape.

Technical terms in everyday language:

- Target distribution : the thing we want to sample from.

- Potential : a way to turn likelihood into a landscape height.

- Ergodicity: the sampler eventually “forgets” where it started and explores the target fairly.

- Exponential ergodicity: it forgets quickly, which is good for efficiency.

- Monte Carlo-Exact: the algorithm’s long-run behavior is exactly right (no bias), thanks to accept/reject steps.

4. What did they find and why does it matter?

The paper’s examples show both successes and failures of standard methods, highlighting why robustness is needed:

- When the target is nice and smooth, standard methods work well.

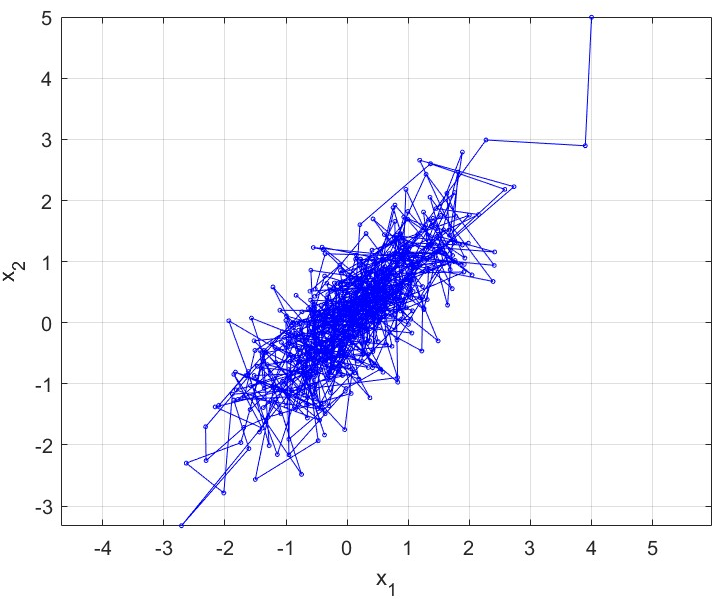

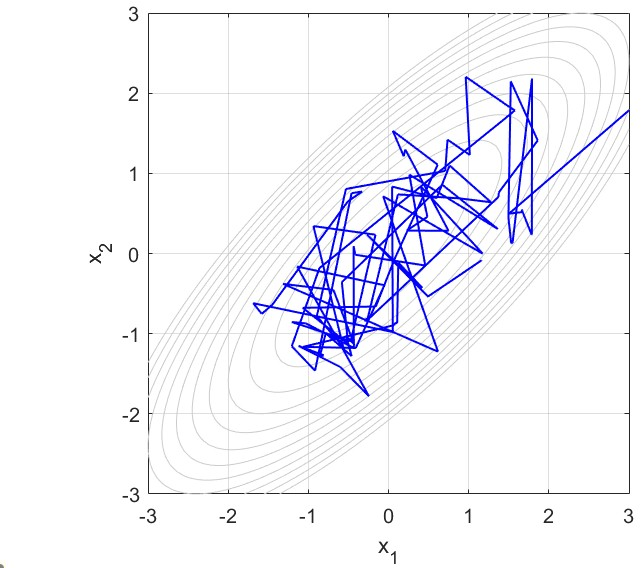

- Example: On a 2D Gaussian, MALA and RHMC explore quickly and produce good samples. RHMC often decorrelates faster (samples are less related to the previous ones), which is a sign of efficiency.

- BPS and ZZS also perform well and can be simulated effectively on such targets.

- Roughness causes serious problems if not handled carefully.

- “Polynomially steep” targets (like ): the slope grows very fast far from the center. MALA can get stuck—constantly rejecting proposed moves—unless the step-size is made very small. But tiny steps make exploration painfully slow.

- “Locally sharp” targets (like Laplace with ): the slope has sharp kinks near zero. In high dimensions, MALA becomes extremely sensitive to step-size: a slightly larger step-size can ruin performance (low acceptance, high error).

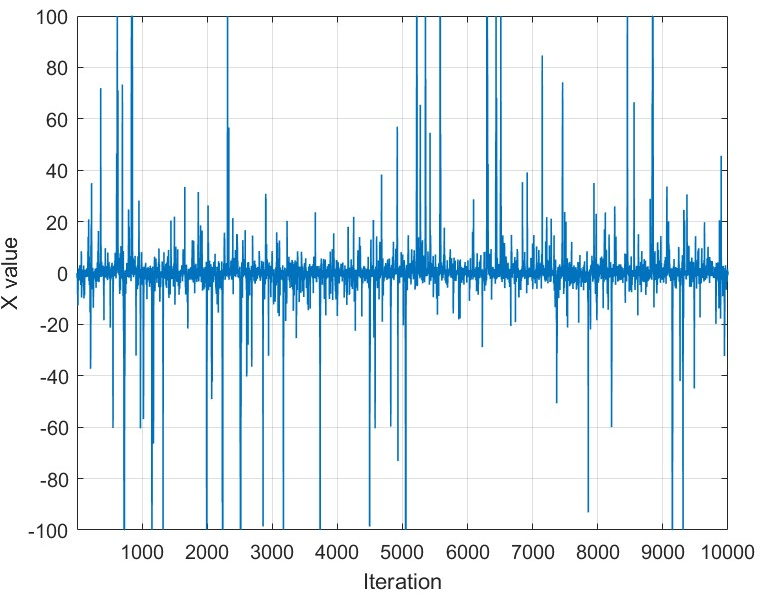

- Flatness or heavy tails (very spread-out distributions) is another major challenge.

- The paper explains that heavy-tailed targets place more probability far away from the center. Standard assumptions (like smoothness and strong “pull” back to the center) may fail, causing slow convergence or instability. Robust methods and careful tuning are needed to avoid wandering or getting stuck.

- Practical takeaways:

- Gradient-based samplers (like MALA) can be fragile when the landscape is too steep or has sharp corners.

- Momentum-based methods (like HMC/RHMC) and PDMPs (BPS, ZZS) often explore faster and can be less sensitive to roughness in some settings.

- Using accept/reject steps (Metropolis-style “sanitizing”) can remove bias from numerical approximations, improving reliability.

Why this matters: In modern statistics and machine learning, we often face complicated, high-dimensional problems where the target distribution isn’t perfectly smooth or well-behaved. Knowing which methods still work—and how to tune or modify them—can make the difference between getting meaningful results or wasting lots of computation.

5. What are the broader implications?

- Robust MCMC is about avoiding worst-case failures, not just being fast when things are easy. The paper encourages designing algorithms that work decently even when the target is rough or heavy-tailed.

- For practitioners: be cautious with step-size tuning, consider momentum-based methods (HMC/RHMC) or PDMP samplers (BPS/ZZS) when gradients are steep or non-smooth, and use accept/reject adjustments to keep long-run behavior correct.

- For researchers: there are promising directions in creating algorithms that adapt to the target’s local geometry (sharpness, roughness) and global behavior (heavy tails) while remaining simple, general-purpose, and efficient.

- Overall, the paper helps bridge theory and practice by explaining what breaks, why it breaks, and how modern methods can be made more reliable in real-world, messy scenarios.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The paper highlights important pathologies for MCMC but leaves several issues unresolved. Below is a concrete, actionable list for future research.

- Lack of rigorous acceptance-rate and mixing-time bounds for

MALA/LMC/RWMwhen the potential has super-quadratic growth (e.g., with ): derive state- and dimension-dependent step-size scaling laws and quantitative convergence guarantees. - No adaptive, state-dependent step-size schemes with proofs of ergodicity for gradient-based samplers under roughness (non-Lipschitz or discontinuous ): design and analyze robust step-size controllers (e.g., taming, truncation, trust-region) that ensure acceptable movement and invariant measure preservation.

- Absence of systematic remedies for local non-differentiability (Laplace-type targets using penalties): evaluate subgradient-based proposals, smoothed/Moreau-envelope targets, and proximal MCMC variants, and establish theoretical guarantees and practical tuning guidance.

- Robust handling of hard boundaries and singularities (e.g., constrained Gaussians, Beta-type densities): develop reflection/refraction rules or constrained versions of

HMC/PDMPwith proofs of correctness, and quantify the bias and failure modes of ad hoc clamping near boundaries. - Missing unified framework that extends modulus-of-continuity assumptions beyond Lipschitz/Hölder to bounded variation or discontinuous gradients: characterize acceptance lower bounds, bias upper bounds, and ergodicity conditions across this spectrum.

- Unclear dimension dependence under roughness: provide precise scaling of step-size, acceptance probability, and computational complexity in high dimension; replace heuristic acceptance targets (e.g., 50–60%) with theoretically justified, dimension-aware tuning rules.

PDMP-specific open problem: automatic, inexpensive construction of tight upper bounds for inhomogeneous event rates from black-box ; design online bounding strategies and quantify their impact on exactness and efficiency.- Efficiency of Metropolis-type “sanitization” for

PDMPdiscretizations: quantify acceptance rates, overhead, and net gains; develop adaptive wrappers and step-size/event-rate tuning policies with theoretical performance guarantees. - Principled tuning of refresh rate and velocity correlation in

RHMCunder roughness or heavy tails: derive selection rules optimizing asymptotic variance and mixing subject to computational budgets. - Lack of comparative benchmarks on rough targets (quartic, Laplace, hard boundaries): run standardized, reproducible head-to-head evaluations of

MALA,RHMC,BPS, andZZSwith matched budgets, reporting spectral gaps, effective sample sizes, and bias. - No diagnostics to detect roughness or flatness on the fly and adapt hyperparameters or switch algorithms while preserving stationarity: design online detectors and safe adaptation mechanisms (e.g., diminishing adaptation with guarantees).

- Interaction of roughness and heavy-tailedness when both occur: develop and analyze methods simultaneously robust to local non-smoothness and poor global confinement; establish ergodicity and mixing results in these compound pathologies.

- Quantitative bias analysis for inexact

PDMPsimulation when exact event timing is infeasible: provide error bounds for common rate-approximation schemes and design MLMC/debiasing strategies tailored toPDMPs. - Geometry and preconditioning for rough, anisotropic targets: construct and analyze position-dependent metrics (Riemannian

MALA/HMC) and anisotropicBPS/ZZS; give implementable recipes for metric learning and stability guarantees. - Gradient truncation/taming for steep potentials within MH-corrected samplers: propose truncation rules that maintain detailed balance (e.g., via modified proposals or Barker acceptance) and prove robustness and efficiency.

- Robustness to noisy or stochastic gradients (e.g., large-scale settings): extend “robust” algorithms to tolerate gradient noise with controlled bias/variance; develop variance-reduction and correction schemes with convergence proofs.

- Theoretical exponential ergodicity for

RHMC,BPS, andZZSunder weak smoothness and in high dimension: move beyond qualitative claims to explicit rates and conditions that cover non-Lipschitz and super-quadratic . - Constrained

PDMPdesigns for polyhedral domains and corners: specify specular reflection or event rules compatible with constraints, and prove invariance and mixing properties under rough boundary geometries. - Heavy-tailedness remedies are not detailed in the provided text: systematically analyze and compare strategies (tempering, heavy-tailed momentum, variable friction, stable-noise SDEs, informed proposals) with theoretical guarantees and practical tuning.

- Practical parameter selection under computational budgets: provide decision procedures to choose step-size, number of leapfrog steps, and event-rate caps that meet target error levels (e.g., total variation, Wasserstein) within a wall-clock budget.

- Limited experimental validation: extend beyond toy 1–2D demos to high-dimensional, real-data targets; release reproducible code and report rigorous metrics (e.g., effective sample size per second, spectral gap estimates, bias across coordinates).

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by adapting existing MCMC workflows to the robustness insights and methods summarized in the paper.

- Robust Bayesian inference with non-smooth priors and constraints

- Sectors: healthcare, finance, software, social sciences

- Use cases: posterior sampling with Laplace/L1-type priors (e.g., Lasso, total-variation priors in imaging), spike-and-slab formulations, quantile/robust regression, truncated or constrained Gaussians (non-negativity constraints).

- Workflow: prefer PDMP samplers such as Bouncy Particle Sampler (BPS) or Zig-Zag (ZZS) when gradients are non-Lipschitz or non-differentiable; avoid standard HMC/MALA near kinks or boundaries. For differentiable regions, use MALA with carefully tuned step sizes to maintain acceptable acceptance rates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to gradients or directional derivatives; ability to simulate inhomogeneous Poisson processes (via thinning with piecewise bounds); sufficient computational budget for event-time PDMP simulation.

- Acceptance-rate-driven tuning for Langevin-based samplers

- Sectors: software, academia, education

- Use cases: tuning MALA on “rough” or “locally sharp” targets to maintain mobility and reduce stickiness.

- Workflow: target 50–60% acceptance (as recommended) in well-behaved cases; on rough targets (e.g., Laplace), perform step-size sweeps and monitor acceptance vs. MSE to avoid catastrophic rejection. Use traceplots and autocorrelation diagnostics to detect “stuck” behavior and shrink step size accordingly.

- Assumptions/dependencies: acceptance-rate diagnostics and automated sweeps; moderate dimensionality or step-size control scaled with dimension.

- Momentum-driven exploration for correlated, moderately smooth targets with RHMC/HMC

- Sectors: ML/AI, healthcare (hierarchical models), physics

- Use cases: posterior sampling in correlated Gaussian-like models, moderate smoothness, where gradient information is reliable but curvature slows random walks.

- Workflow: adopt refreshed Hamiltonian dynamics (RHMC) with leapfrog integrator and periodic velocity refresh; select refresh rate λ and correlation ρ to reduce autocorrelation; keep Metropolis wrapper if exactness is required and dynamics are only approximated.

- Assumptions/dependencies: differentiable log-densities; compatible integrators; proper tuning of integration length and refresh parameters.

- Event-time samplers for rough gradients with bias control

- Sectors: software, academia

- Use cases: models where gradient magnitudes explode (light tails beyond Gaussian, e.g., quartic potentials), causing MALA/HMC instability.

- Workflow: deploy BPS/ZZS with numerical event-rate approximation (piecewise-constant/linear bounds) and use a Metropolis-type wrapper to remove discretization bias (per recent PDMP wrappers).

- Assumptions/dependencies: event-rate bounds and thinning; wrapper implementation; monitoring of discretization bias vs. Monte Carlo variance.

- Efficient simulation of Markov jump processes (MJPs) in stochastic kinetics and epidemiology

- Sectors: healthcare, biotech, public policy (epidemiology)

- Use cases: biochemical networks, disease progression models, queueing systems.

- Workflow: use Gillespie’s Doob-Gillespie algorithm for exact MJP simulation when tractable; switch to tau-leaping for large systems with controlled bias; consider multilevel Monte Carlo to keep bias below Monte Carlo variance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: known hazard rates; computational control over tau-leaping error; availability of MLMC estimators for bias quantification.

- Boundary-aware sampling in constrained models

- Sectors: healthcare, energy, operations research

- Use cases: truncated normals, inequality constraints in physical models, resource planning with bounds.

- Workflow: avoid naive gradient-based proposals near boundaries; use PDMPs (specular reflections or component flips) or constrained HMC variants; reparameterize to unconstrained space when possible.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable constraint handling (reflections or transforms); ability to implement event rules tied to boundary geometry.

- Practical diagnostic checklist for robustness

- Sectors: software, academia, education

- Use cases: pre-run model audits to prevent failure modes (stickiness, poor mobility, exploding costs).

- Workflow: check modulus-of-continuity proxies for ∇log π; test acceptance-rate vs. step-size; inspect traceplots/autocorrelation; test behavior near boundaries; pick sampler class (MALA/HMC vs. BPS/ZZS) accordingly.

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to gradient evaluations; diagnostic tooling; fixed computational budget for exploratory runs.

Long-Term Applications

These applications will benefit from further research, scaling, integration into mainstream tools, or development of supporting theory and automation.

- Automated pathology detection and sampler selection

- Sectors: software, ML/AI platforms, academia

- Use cases: end-to-end inference platforms that detect “roughness” (non-Lipschitz, non-smooth), “flatness/heavy tails,” and boundaries, and automatically choose/tune samplers (MALA/HMC vs. BPS/ZZS vs. RWM).

- Product concept: an “Auto-Robust MCMC” layer that estimates local smoothness, tail behavior, and dimension scaling, then configures event-time samplers and step sizes; integrates acceptance targets and thinning bounds.

- Dependencies: fast estimators of continuity moduli; reliable tail-behavior diagnostics; robust cross-sampler APIs; theory to guarantee graceful degradation across regimes.

- PDMP samplers integrated in mainstream probabilistic programming

- Sectors: software (Stan, PyMC, NumPyro, Turing), ML platforms

- Use cases: adding BPS/ZZS with event-time simulation and Metropolis-type bias sanitization into mainstream toolchains.

- Workflow: backend support for inhomogeneous Poisson thinning, piecewise rate bounding, automated refresh rules, and combined PDMP + HMC pipelines for hybrid targets.

- Dependencies: platform-level support for event-time computation; gradient or directional derivative interfaces; maintainability and benchmarking at scale.

- Learned event-rate surrogates and adaptive thinning

- Sectors: ML/AI, software

- Use cases: fast PDMP simulation by learning bounds on event rates with models that adapt to local geometry, reducing rejection in thinning.

- Workflow: train surrogate models or use online estimation of rate bounds; plug into PDMP event simulators with safety constraints; apply Metropolis wrapper for exactness when needed.

- Dependencies: safe surrogate training with formal guarantees; calibration methods to avoid bias; runtime controllers for adapting bounds.

- Robust heavy-tail inference pipelines

- Sectors: finance, insurance, energy risk, cybersecurity

- Use cases: posteriors with substantial mass far from modes; operational risk, extreme events.

- Workflow: combine PDMP methods with tailored proposals and step-size policies that preserve mobility in heavy tails; multilevel corrections to manage bias; monitoring of geometric ergodicity.

- Dependencies: rigorous heavy-tail diagnostics and tuning rules; scalable MLMC integration; acceptance-rate targets adapted to tail exponents.

- High-performance continuous-time MCMC for HPC and real-time inference

- Sectors: healthcare (clinical decision support), finance (intraday risk), robotics (SLAM), energy (grid reliability)

- Use cases: low-latency sampling with reduced autocorrelation using RHMC or PDMP on clusters/GPUs.

- Workflow: event-time execution engines that exploit parallel thinning, vectorized rate evaluation, and GPU-based leapfrog; pipeline integration with streaming data.

- Dependencies: optimized libraries for ODE and event simulation; GPU/TPU kernels for gradient and rate computations; robust fault-tolerant controllers.

- Bias-aware numerical MCMC components

- Sectors: academia, software

- Use cases: numerical discretizations (Euler-Maruyama, splitting schemes) with formal bias control via multilevel Monte Carlo and Metropolis sanitization.

- Workflow: integrate MLMC estimators directly into sampling loops; expose tolerances so the bias stays beneath Monte Carlo variance.

- Dependencies: efficient multilevel estimators; interfaces for bias/variance budgeting; theoretical guarantees in high dimension.

- Education and standards for robust MCMC practice

- Sectors: academia, policy (methodological standards)

- Use cases: curricula and best-practice guidelines for diagnosing and mitigating robustness issues in applied modeling (epidemiology, environmental policy).

- Workflow: standardized checklists, acceptance-rate heuristics, sampler selection maps, boundary-handling templates; reproducible benchmarks for robustness.

- Dependencies: community consensus on diagnostics and thresholds; accessible, well-documented exemplar code bases; open datasets for stress-testing.

Each long-term application assumes continued progress on event-time simulation tooling, theory for robustness under weakened smoothness and tail conditions, and integration into widely used probabilistic programming ecosystems.

Glossary

- Acceptance probability: The probability with which a proposed move is accepted in a Metropolis–Hastings-type algorithm. "evaluates the Metropolis-Hastings acceptance probability "

- Aperiodicity: A property of a Markov chain indicating it does not get trapped in cyclic behavior, contributing to convergence guarantees. "irreducibility, aperiodicity, and a meaningful form of ergodicity."

- Asymptotic variance: The long-run variance of estimators based on MCMC samples, often minimized by tuning algorithm parameters. "which is conjectured to be optimal in terms of minimising the asymptotic variance"

- Auxiliary variable: An extra variable introduced to augment the state space to facilitate sampling or algorithm design. "augmenting with an auxiliary variable "

- Bouncy Particle Sampler (BPS): A PDMP-based MCMC algorithm using deterministic motion and velocity reflections determined by the target’s gradient. "We consider the two-dimensional correlated Gaussian (\ref{eq:2d.Gauss}) of the previous sub-sections to showcase the performance of the Bouncy Particle Sampler (BPS)"

- Central Limit Theorems: Results that describe the normal convergence of properly normalized sums or averages, applied to MCMC ergodic averages. "Laws of Large Numbers, Central Limit Theorems, Concentration Inequalities"

- Concentration Inequalities: Bounds that quantify how a random variable deviates from some value (like its mean), used to assess MCMC estimator reliability. "Laws of Large Numbers, Central Limit Theorems, Concentration Inequalities"

- Doob-Gillespie algorithm: An exact simulation algorithm for Markov jump processes commonly used in biochemical systems. "Doob-Gillespie algorithm (initially introduced as a practical method in \cite{gillespie1977exact} for biochemical simulations; see also \cite{anderson2015stochastic})."

- Euler-Maruyama discretisation: A numerical scheme to approximate solutions of SDEs, foundational for LMC/ULA. "Application of a straightforward Euler-Maruyama discretisation to the Langevin process leads to the `Unadjusted Langevin Algorithm' (ULA)"

- Ergodic averages: Averages computed along the trajectory of a Markov chain, used for estimating expectations under the target distribution. "for ergodic averages along the MCMC trace"

- Ergodicity: The property that a Markov chain will eventually explore the state space according to its invariant distribution. "Under rather mild conditions on , this process is both reversible and ergodic with respect to "

- Exponential ergodicity: A strong convergence property where the distance to the target distribution decays exponentially fast. "a more demanding condition which should be satisfied by `good' MCMC kernels is exponential ergodicity"

- Free transport: Deterministic motion with constant velocity, used as the flow in PDMPs like BPS and Zig-Zag. "The dynamics in question are simple free transport, i.e. "

- Gauss-Markov processes: A tractable class of stochastic processes that allow some exact simulation methods for SDEs. "either those with substantial analytic tractability (e.g. Gauss-Markov processes)"

- Geometric Numerical Integration: A field of numerical analysis focusing on structure-preserving methods for dynamical systems. "have been especially well-served by the field of Geometric Numerical Integration \cite{hairer2003geometric}."

- Gibbs sampler: An MCMC method that samples iteratively from conditional distributions, often considered a non-local sampler. "The chief example of this class is the Gibbs sampler"

- Hamiltonian dynamics: Deterministic dynamics defined by Hamilton’s equations, used in HMC/RHMC. "numerical methods for Hamiltonian dynamics are rather well-developed"

- Hamiltonian Monte Carlo: An MCMC method leveraging Hamiltonian dynamics with a Metropolis correction to sample efficiently from complex targets. "this is typically what is meant by (Metropolised) `Hamiltonian Monte Carlo'."

- Heavy-tailedness: A property of distributions with substantial probability mass far from the center, challenging for MCMC. "we focus on the sibling pathology of `heavy-tailedness' of the target distribution"

- Hit-and-Run: A non-local MCMC method that proposes moves uniformly along random directions in the state space. "Hit-and-Run \cite{belisle1993hit, rudolf2013hit}"

- Hölder-type smoothness: A smoothness condition weaker than Lipschitz, controlling gradients via a power-law modulus of continuity. "for polynomial (corresponding to smoothness of Hölder type)"

- Inhomogeneous Poisson point processes: Poisson processes with time-varying rates used for simulating PDMP event times. "certain inhomogeneous Poisson point processes are feasible to simulate"

- Irreducibility: A Markov chain property ensuring any state can be reached from any other (in a suitable sense), crucial for convergence. "irreducibility, aperiodicity, and a meaningful form of ergodicity."

- Itô SDE: A stochastic differential equation interpreted in the Itô sense, central to Langevin diffusions. "the overdamped Langevin diffusion targeting is the It^{o} SDE given by"

- Langevin Monte Carlo (LMC): A sampling method based on discretizing Langevin dynamics without Metropolis correction (also called ULA). "also `Langevin Monte Carlo' (LMC)"

- Law of Large Numbers: A theorem guaranteeing convergence of sample averages to expected values, applicable to MCMC estimators. "Laws of Large Numbers, Central Limit Theorems, Concentration Inequalities"

- Lebesgue measure: The standard measure on Euclidean space used to define densities of continuous distributions. "density of the measure with respect to the Lebesgue measure"

- Leapfrog: A symplectic integrator used in HMC to numerically simulate Hamiltonian dynamics. "the splitting integrator of (St\o{}rmer-Verlet, Leapfrog, Strang, etc.)"

- Level sets: Sets of points where a function (e.g., log-density) takes the same value; used to define reflections in BPS. "the level sets of the log-density"

- Light-tailedness: A property of distributions whose tails decay faster (e.g., log-concave), typically easier for MCMC. "various light (typically tails lighter than Gaussian) and heavy (tails heavier than Laplace) densities."

- Log-concave: A functional property indicating that the log-density is concave, often implying good mixing for Langevin-based samplers. "asymptotically approximately log-concave at infinity"

- Metropolis-Adjusted Langevin Algorithm (MALA): A gradient-based Metropolis–Hastings method using Langevin proposals. "Finally, to take the Langevin diffusion into the Monte Carlo-Exact paradigm, application of the Metropolis-Hastings device to the aforementioned Euler-Maruyama discretisation yields the so-called Metropolis-Adjusted Langevin Algorithm (MALA)"

- Metropolisation: The addition of an accept/reject step to correct bias in approximate dynamics. "which is known as the Metropolis-Hastings filter or simply ``Metropolisation")"

- Metropolis-Hastings filter: The accept/reject mechanism ensuring exact invariance of the target in MH algorithms. "which is known as the Metropolis-Hastings filter"

- Metropolis-Hastings acceptance probability: The MH rule determining acceptance based on target and proposal densities. "evaluates the Metropolis-Hastings acceptance probability "

- Metropolis-type wrapper: A MH-based outer layer added to sanitize biased discretizations by restoring exact invariance. "proposes a Metropolis-type wrapper which allows to `sanitise' some of these discretisations"

- Modulus of continuity: A function bounding the change in the gradient, used to characterize roughness and step-size tuning. "a more general modulus of continuity assumption"

- Monte Carlo-Exact paradigm: Designing implementable kernels whose invariant measure matches the target exactly using accept/reject. "we term this the Monte Carlo-Exact paradigm for MCMC."

- Multilevel Monte Carlo: A variance reduction and bias control technique using coupled discretizations at multiple levels. "Among such strategies, we highlight Multilevel Monte Carlo"

- Piecewise-Deterministic Markov Processes (PDMPs): Continuous-time processes with deterministic flows and random jumps, used for MCMC. "For Piecewise-Deterministic Markov Processes (PDMPs), exact simulation is possible in some cases"

- Potential: The negative log-density U(x) used to define forces and energies in MCMC dynamics. " will sometimes be called {\it the potential}."

- Potential energy: The component of the Hamiltonian derived from the target density; Kinetic energy is defined similarly. "with being called the {\it potential} energy."

- Random Walk Metropolis: A Metropolis–Hastings algorithm using symmetric random-walk proposals. "Random Walk Metropolis \cite{sherlock2010random, andrieu2024explicit}"

- Randomised Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (RHMC): A variant of HMC with randomized velocity refreshes in continuous time. "introduced by \cite{bou2017randomized} as `Randomised Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (RHMC)'"

- Refreshed Hamiltonian Dynamics: A PDMP combining Hamiltonian flow with random velocity refreshments. "For Refreshed Hamiltonian Dynamics (introduced by \cite{bou2017randomized} as `Randomised Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (RHMC)'"

- Reversible with respect to π: A symmetry property of the kernel ensuring detailed balance relative to the target. "it is common to even impose that the kernel be reversible with respect to "

- Slice Sampling: An auxiliary-variable MCMC method that samples by defining slices under the target density. "Slice Sampling \cite{neal2003slice, rudolf2013hit}"

- Specular reflection: The velocity update at BPS events reflecting against the gradient-defined surface. "the velocity undergoes a specular reflection against the level sets of the log-density"

- Splitting schemes: Numerical integrators that decompose dynamics into solvable substeps, used for ODEs/SDEs in MCMC. "like splitting schemes becomes appealing"

- Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs): Differential equations driven by randomness, foundational for Langevin-based MCMC. "For Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs) of It^{o} type"

- St\o{}rmer-Verlet: A symplectic splitting integrator widely used in HMC for Hamiltonian systems. "the splitting integrator of (St\o{}rmer-Verlet, Leapfrog, Strang, etc.)"

- Tau-leaping: An approximate method for simulating large Markov jump processes by leaping over small time intervals. "approximation strategies such as tau-leaping"

- Total variation distance: A metric on probability measures used to quantify convergence of Markov chains. "We write to denote the total variation distance"

- Unadjusted Langevin Algorithm (ULA): The Euler–Maruyama discretization of Langevin dynamics without a Metropolis correction. "the

Unadjusted Langevin Algorithm' (ULA), alsoLangevin Monte Carlo' (LMC)" - Wiener process: Standard Brownian motion driving stochastic dynamics in Langevin SDEs. " is a usual Wiener process on ."

- Zig-Zag Process: A PDMP with piecewise-linear motion and coordinate-wise velocity flips, used for MCMC. "The Zig-Zag Process has a similar character"

- Zig-Zag Sampler (ZZS): The practical sampler based on the Zig-Zag process, often implemented without refreshment. "Zig-Zag Sampler (ZZS) on a two-dimensional correlated Gaussian"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.