Causal Inference: A Tale of Three Frameworks (2511.21516v1)

Abstract: Causal inference is a central goal across many scientific disciplines. Over the past several decades, three major frameworks have emerged to formalize causal questions and guide their analysis: the potential outcomes framework, structural equation models, and directed acyclic graphs. Although these frameworks differ in language, assumptions, and philosophical orientation, they often lead to compatible or complementary insights. This paper provides a comparative introduction to the three frameworks, clarifying their connections, highlighting their distinct strengths and limitations, and illustrating how they can be used together in practice. The discussion is aimed at researchers and graduate students with some background in statistics or causal inference who are seeking a conceptual foundation for applying causal methods across a range of substantive domains.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about a big idea called causal inference: how to figure out what causes what. For example, does a job-training program really help people get jobs, or do people who would have found jobs anyway just happen to join it? The authors compare three major “toolkits” that scientists use to ask and answer causal questions. Even though these toolkits use different language and pictures, they often agree, and you can translate ideas from one to another.

What questions is the paper trying to answer?

- How do the three main causal frameworks—Potential Outcomes, Structural Equation Models (SEMs), and Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs)—work?

- How are they similar and different?

- When do they give the same answers?

- What are the strengths and limits of each?

- How can we use them together to answer real-world causal questions more clearly and reliably?

How the three approaches work (with simple analogies)

To make things concrete, imagine a job-training program (A) that might affect whether someone gets a job (Y). People also have background traits (L) like education or motivation that can affect both.

1) Potential Outcomes: “two what-if worlds”

- Idea: For each person, imagine two parallel worlds:

- World 1: they do not get the program (A=0), and they have an outcome Y(0).

- World 2: they do get the program (A=1), and they have an outcome Y(1).

- We can’t see both worlds for the same person in real life (that’s the “fundamental problem”).

- So we focus on averages, like the average treatment effect: the average difference Y(1) − Y(0) across people.

- Key assumptions in simple terms:

- Consistency: if someone actually gets the program, their observed outcome equals the “treated” outcome from the what-if world Y(1).

- No interference: your outcome isn’t affected by what others get (no spillovers).

- No hidden bias after adjusting for L (ignorability): if we compare people with the same L, who got treated or not is “as if random.”

- How we estimate: “Level the playing field” by adjusting for L (e.g., via regression, matching, or weighting), then compare outcomes as if it were randomized.

2) Structural Equation Models (SEMs): “a machine with modules”

- Idea: Think of the world as a machine with boxes and knobs. Each variable (L, A, Y) comes from a rule:

- L = some function of unobserved stuff (randomness)

- A = some function of L and unobserved stuff

- Y = some function of L, A, and unobserved stuff

- An intervention is like reaching in and flipping a switch: set A = a and leave the other boxes alone.

- Key assumption: Autonomy (also called modularity). Each box (mechanism) keeps working the same way even if you change another box by intervention.

- Sometimes SEMs also assume the unobserved noises are independent. That’s stronger and can help identify more causal effects—but only if it’s true.

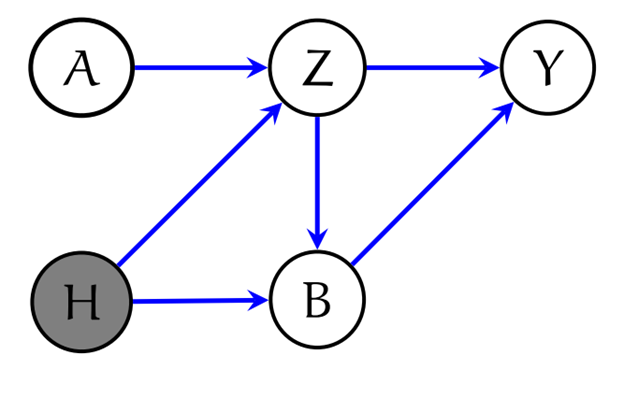

3) Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs): “a cause-and-effect map”

- Idea: Draw variables as circles and arrows for direct causes (e.g., L → A → Y, and L → Y).

- What the map helps with:

- Seeing where confounding comes from (paths that “sneak” from A to Y through other causes like L).

- Choosing what to adjust for to block bad paths (the “backdoor” idea: adjust for L to block L → A and L → Y).

- Intervening is like removing arrows that point into A and then asking, “What happens now?”

- DAGs come with rules for when paths are “blocked” or “open” (called d-separation) that tell you when variables are independent given others. This helps you decide if a causal effect can be identified from data.

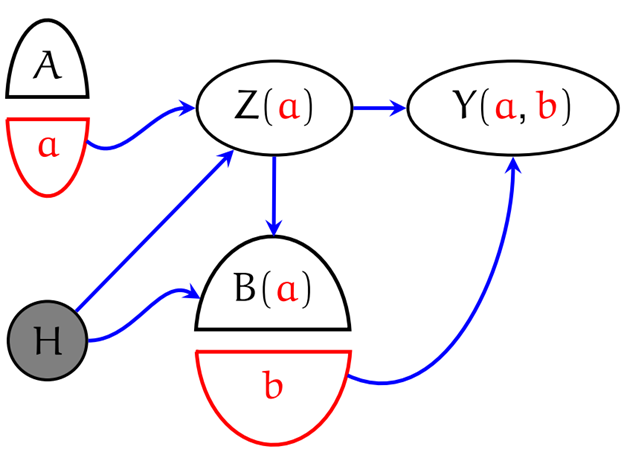

A bridge between them: SWIGs

- SWIGs (Single World Intervention Graphs) combine the clarity of potential outcomes with the visual power of graphs. They draw potential outcomes directly on a modified DAG, helping translate between the “two what-if worlds” and the “map.”

What did the authors find?

- The three frameworks often agree and can be translated:

- Potential Outcomes’ “adjust for L” lines up with DAGs’ “backdoor criterion.”

- SEMs’ “flip the switch and keep all other boxes the same” matches DAGs’ “remove incoming arrows and recompute” and Potential Outcomes’ “consistency.”

- The g-formula (a math recipe for computing effects after adjustment) appears in all three frameworks, just written differently.

- Each framework has special strengths:

- Potential Outcomes: very clear definitions of effects (like average treatment effect), great for paper design and policy questions.

- DAGs: great for seeing where confounding comes from, deciding what to adjust for, and checking if identification is possible.

- SEMs: powerful for modeling complex systems and predicting effects of interventions, especially if you’re willing to assume stable, independent “mechanisms.”

- But each has limits:

- Potential Outcomes need assumptions like no hidden confounding and no interference, which can be hard in networks or epidemics.

- DAGs are about structure and independence; they don’t by themselves give numbers without data and assumptions.

- SEMs can identify more if you assume strong things (like independent error terms), but those assumptions might be wrong in practice.

- The paper shows how to move between frameworks and when the extra assumptions (like independence of errors in SEMs) are helpful or risky.

- It also clarifies the difference between interventional questions (“What if we set A to 1 for everyone?”) and counterfactual questions about specific individuals (“Given what actually happened to me, what if I had chosen differently?”). The second type usually needs stronger, often untestable assumptions.

Why this matters

- Scientists in many fields—medicine, economics, education, public policy, and even AI—need reliable ways to tell cause from correlation.

- Using these frameworks together can make causal studies more transparent, more accurate, and easier to check:

- Define the effect clearly (Potential Outcomes).

- Draw the causal map to see what to adjust for (DAGs).

- Use a model of mechanisms to predict what happens under interventions (SEMs), when appropriate.

- This combined approach helps build trustworthy systems (e.g., in AI) that don’t just predict but also explain and remain stable when conditions change.

Takeaway

If you think of causal inference as solving a mystery—what really caused what—then:

- Potential Outcomes give you clear “what-if” questions.

- DAGs give you a map showing where to look and what traps to avoid.

- SEMs give you a working model of the machine you’re investigating. Together (with tools like SWIGs) they help you ask better questions, make safer assumptions, and draw stronger conclusions about cause and effect.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, consolidated list of concrete gaps the paper leaves unresolved and that future work could address.

- Precise equivalence conditions across frameworks: Specify necessary and sufficient conditions under which a system of potential outcomes, an NPSEM (with or without independent errors), and a causal DAG (or ADMG) yield identical identification results for a given set of interventional estimands.

- Testability of autonomy/modularity and independent errors: Develop empirical tests, falsifiable constraints, or diagnostics (beyond qualitative argument) to assess the autonomy/modularity and independent-error assumptions of NPSEMs using observational and interventional data.

- Systematic handling of ill-defined treatments and consistency violations: Create formal procedures to (i) disambiguate compound or context-dependent “treatments,” (ii) refine interventions so consistency holds, and (iii) characterize the impact of treatment heterogeneity on identification in each framework.

- Positivity/overlap violations: Provide identification strategies and practical remedies (e.g., partial identification, trimming, transport via modeling) that are explicitly mapped across potential outcomes, DAGs, and NPSEMs when treatment assignment lacks sufficient overlap.

- Unified sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding: Develop a framework-agnostic sensitivity analysis that transparently translates between ignorability (potential outcomes), causal sufficiency/backdoor (DAGs), and independent-errors (NPSEM-IE), including clear guidance on parameterization, interpretation, and robustness guarantees.

- Minimal assumptions for counterfactual estimands: Identify the weakest assumptions (and their framework-specific formulations) under which quantities like persuasion rate, probability of necessity/sufficiency, and joint counterfactuals become identifiable, and provide constructive identification formulas or bounds.

- Cycles and feedback: Expand the discussion to cyclic SEMs with feedback and articulate how (and when) SWIGs/DAGs can represent or approximate such systems; delineate identification results and limitations for cyclic causal models.

- Interference and network effects: Formulate a unified treatment of interference (partial and general), including SWIG/ADMG representations, associated identification conditions (e.g., exposure mappings), and translation of these conditions into potential outcomes and NPSEM language.

- Measurement error and latent constructs: Provide a cross-framework treatment of measurement error and latent-variable models, including conditions under which identification survives measurement noise, misclassification, or proxy variables.

- Causal discovery under latent confounding: Clarify how constraint-based or score-based methods (e.g., FCI, PAGs) relate to NPSEM assumptions and SWIG representations; state guarantees and failure modes when causal sufficiency is violated.

- Faithfulness and strong-faithfulness in practice: Offer quantitative diagnostics to assess (strong) faithfulness from data, with finite-sample guarantees and clear guidance on thresholds (λ) that balance false acceptance and false rejection in structure learning.

- External validity and transportability: Integrate transportability/selection diagrams and invariance-based reasoning across the three frameworks; specify actionable criteria and algorithms for transporting causal conclusions across environments with distributional shift.

- Multi-stage/adaptive interventions: Systematically connect g-methods/dynamic treatment regimes to DAGs, NPSEMs, and SWIGs for sequential decision-making; enumerate identification conditions and provide example mappings for time-varying treatments and policies.

- Mediation and path-specific effects: Present a unified approach to identifying natural/controlled direct and indirect effects (including path-specific effects) across frameworks, clarifying added assumptions (e.g., cross-world independence) and when they are defensible.

- Front-door and instrumental-variable identification: Expand the comparative treatment to include front-door criteria and IV assumptions, explaining their counterparts in NPSEM-IE and potential outcomes, and how they alter identification power and robustness.

- Practical variable selection for adjustment (L): Provide principled procedures for choosing covariates that satisfy ignorability/backdoor criteria in high dimensions, with statistical guarantees and guidance on regularization, feature selection, or representation learning.

- Missing data and selection bias beyond the “fundamental problem”: Address MNAR mechanisms and selection bias within each framework; delineate identification conditions and practical estimators that remain valid under nonresponse or sample selection.

- Quantile and distributional effects: Detail identification conditions for QTEs and other distributional estimands in each framework, including when they require stronger assumptions than ACE and how violations (e.g., rank invariance) can be handled via bounds.

- Do-calculus vs. g-formula/ID algorithm mapping: Provide an explicit translation between do-calculus rules, the g-formula, and the ID algorithm (including SWIG-based identification), indicating when NPSEM-IE assumptions strictly expand the space of identifiable targets.

- Empirical guidance, workflows, and software: Offer concrete decision rules and reproducible pipelines (including SWIG tooling) that help practitioners choose a framework, check assumptions, run identification tests, and report sensitivity analyses consistently.

- Benchmark case studies: Include comparative empirical examples across domains (e.g., healthcare, economics, networks) demonstrating how the three frameworks lead to differing assumptions, identification results, and practical decisions in realistic data settings.

Glossary

- Acyclic Directed Mixed Graph (ADMG): A graphical model with directed and bidirected edges that is acyclic, often used to represent unmeasured confounding. "resulting in an Acyclic Directed Mixed Graph (ADMG)~\citep{richardson2003markov}."

- Average Causal Effect (ACE): The expected difference in outcomes if everyone received treatment versus control. "the ACE captures the expected difference in outcomes had everyone in the population received treatment versus control."

- Autonomy: The assumption that each structural equation represents an invariant mechanism unaffected by interventions on other variables. "The key assumption in the SEM framework that links the observational world to interventional worlds is the autonomy assumption"

- Backdoor criterion: A graphical condition for identifying causal effects by blocking backdoor paths with covariates. "under this assumption, graphical tools such as the backdoor criterion provide effect-specific tests for identification across multiple treatmentâoutcome pairs."

- Backdoor path: A non-causal path from a cause to an effect that begins with an arrow into the cause. "A particularly important class of non-causal paths are the backdoor paths, which are paths from to that begin with an arrow into ."

- Bayesian network: A probabilistic DAG that encodes conditional independence via factorization. "a DAG is sometimes referred to as a Bayesian network \citep{pearl1985bayesian}"

- Causal DAG model: A DAG endowed with interventional semantics via modularity and the truncated factorization. "A causal DAG model over random variables consists of a directed acyclic graph and a family of interventional distributions "

- Causal ordering algorithm: A procedure to obtain a causal ordering consistent with an acyclic structural system. "as obtained from Simon's causal ordering algorithm \citep{simon1953causal}"

- Causal sufficiency: The assumption that the graph includes all common causes of variables in the model. "it is often assumed that the set of variables is causally sufficient, in the sense that there are no unmeasured common causes that cause two or more variables in "

- Causally Interpretable Structured Tree Graph (CISTG): A representation equivalent to an NPSEM without error independence assumptions. "The {\em Causally Interpretable Structured Tree Graph (CISTG) as detailed as the data} \protect\citep{robins1986new} is mathematically equivalent to an NPSEM model (with no assumption on the errors)"

- Collider: A node where two directed edges meet head-to-head; conditioning on it can open paths. "A collider such that neither nor any of its descendants is in ."

- Conditional Average Treatment Effect (CATE): The average treatment effect within a subpopulation defined by covariates. "Conditional Average Treatment Effect (CATE), defined as "

- Consistency: The assumption that the observed outcome under the received treatment equals the corresponding potential outcome. "Y = Y(a) \quad \text{if } A = a, \quad \text{or equivalently,} \quad Y = Y(A)."

- Counterfactual: A quantity referring to what would have happened under an alternative scenario given the factual outcome. "Potential outcomes are sometimes referred to as counterfactuals in the literature."

- Dirichlet prior: A commonly used prior over categorical probability tables in Bayesian modeling. "by drawing each conditional probability table independently from a prior"

- Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG): A directed graph with no cycles, used to represent causal or probabilistic relationships. "A Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) is a finite set of nodes connected by directed edges such that no cycles are present."

- d-separation: A graphical criterion to infer conditional independencies from a DAG. "then and are said to be d-separated by "

- do-calculus: A set of rules for reasoning about interventions in causal graphs. "This truncated factorization forms the basis of Pearl's do-calculus"

- do-operator: Notation used to denote interventions that set variables to fixed values. "Pearlâs do-operator \citep{pearl2009causality}, written as ."

- Endogenous variables: Variables determined within a structural system by its equations. "the variables in are referred to as endogenous variables because their values are determined within the system by the structural equations."

- Exogenous variables: External random variables representing background factors not determined by the system. "the components of are called exogenous variables, as they represent factors external to the system"

- Faithfulness: The assumption that all and only the conditional independencies in the distribution are entailed by d-separation in the graph. "we say that the distribution is faithful to the graph."

- Functional representation lemma: A result used to construct structural equations consistent with a given causal DAG. "how NPSEMs can, in turn, be generated from a given causal DAG using the functional representation lemma."

- G-formula: The formula that expresses interventional distributions via observational conditionals and marginals. "the g-computation algorithm formula or simply the g-formula."

- Global Markov Property: A property relating d-separation in a DAG to conditional independence in the distribution. "Global Markov Property: For any disjoint sets , if d-separates and in , then"

- Identification: The ability to express a causal estimand uniquely in terms of the observed data distribution. "Identification of counterfactual estimands is typically much more involved"

- Ignorability: The assumption that treatment is independent of potential outcomes given covariates. "Ignorability\textsuperscript{a}: "

- Interventional sufficiency: A condition ensuring that interventional distributions obey the truncation formula despite some hidden variables. "This assumption may be slightly relaxed to the notion of interventional sufficiency, which is sufficient to ensure that the truncation formula~\eqref{eqn:truncated-distribution} holds"

- Latent projection: The operation of marginalizing out unobserved nodes to obtain mixed graphs over observed variables. "such graphs can be obtained as latent projections of DAGs with unobserved variables"

- Lebesgue measure zero: A measure-theoretic notion indicating a set is negligible in continuous parameter spaces. "the set of distributions unfaithful to a graph has Lebesgue measure zero"

- Local Markov Property: Each node is independent of its non-descendants conditional on its parents. "Local Markov Property: Each variable is conditionally independent of its non-descendants given its parents:"

- Markov Factorization Property: The factorization of a joint distribution according to the DAG’s parent sets. "Markov Factorization Property: The joint distribution factorizes as:"

- Modularity: The principle that interventions alter only the mechanism of targeted variables without changing others. "Modularity: intervention modeled by removing incoming edges"

- Moral graph: An undirected graph formed by marrying parents and dropping edge directions to test separations. "d-separation can be defined using the notion of ``moral graph''"

- Nonparametric Structural Equation Models (NPSEM): Structural models specifying variable-generating functions without parametric restrictions. "A key assumption in many NPSEM applications is that the exogenous variables in are jointly independent"

- NPSEM-IE: An NPSEM with the added assumption that exogenous errors are jointly independent. "yielding the special case known as the NPSEM with Independent Errors (NPSEM-IE)."

- Positivity condition: The requirement that all treatment levels have positive probability across covariate strata. "Under this assumption and a positivity condition that ensures all levels of treatment are possible across values of "

- Potential outcomes: Hypothetical outcomes under alternative treatments for the same unit. "The potential outcomes framework provides an intuitive and mathematically tractable foundation for causal inference."

- Principle of independent mechanisms (PIM): The idea that causal modules are independent and invariant to changes in upstream distributions. "The independent error and autonomy assumptions in the NPSEM-IE framework imply the principle of independent mechanisms (PIM)"

- Quantile Treatment Effect (QTE): The difference between treatment and control outcome quantiles at a given percentile. "The Quantile Treatment Effect (QTE), expressed as "

- Single World Intervention Graphs (SWIGs): Graphs that display potential outcomes on a modified DAG to bridge frameworks. "Single World Intervention Graphs (SWIGs), which integrate the graphical and potential outcomes approaches"

- Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA): Assumption of no multiple versions of treatment and no interference between units. "A crucial component of the Potential Outcome framework is the Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA)"

- Structural Causal Models (SCMs): A term often used for NPSEM or specifically NPSEM-IE in the literature. "The term Structural Causal Models (SCMs) is often used in the literature."

- Structural Equation Models (SEMs): Models defining variables via structural functions of parents and exogenous errors. "Structural equation models"

- Truncation formula: The formula for interventional distributions obtained by removing factors corresponding to intervened variables. "and the truncation formula \citep{pearl2009causality}."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed with existing data, methods, and tooling, provided that their assumptions are carefully vetted and documented.

- Healthcare: effect estimation from observational data when randomization is infeasible

- Use case: Estimate average causal effects (ACE) of treatments, procedures, or care pathways using the g-formula, inverse probability weighting, or doubly robust methods; select adjustment sets using the backdoor criterion to avoid post-treatment bias.

- Tools/workflows: DAG construction (DAGitty, Tetrad), potential-outcomes estimators (zEpid, DoWhy, EconML), SWIGs for assumption transparency; workflow: define estimand → draw DAG → check backdoor → verify positivity → estimate ACE/CATE → sensitivity analysis.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consistency (well-defined treatment), SUTVA (no interference or partial-interference design), conditional ignorability given measured covariates L, positivity, correct measurement of pretreatment confounders, causal sufficiency or defensible handling of latent confounding.

- Public policy and program evaluation (e.g., job training, education, social services)

- Use case: Evaluate program effectiveness (ACE, ETT, CATE, QTE), design adjustments to avoid selection bias, and communicate assumptions to stakeholders via SWIGs.

- Tools/workflows: Potential outcomes with g-formula; matching/IPW/TMLE; DAG-based covariate selection; reporting templates that explicitly separate interventional questions from counterfactual ones.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ignorability (selection on observables), clarity on “versions of treatment,” positivity; careful distinction between interventional estimands and counterfactual quantities (e.g., persuasion rate) that typically require stronger, untestable assumptions.

- Technology/software product experimentation and metrics governance

- Use case: Design A/B tests and quasi-experiments informed by DAGs to avoid collider bias and post-treatment adjustment; document causal pathways for feature changes; use SWIGs to label potential outcomes and avoid target leakage in metrics.

- Tools/workflows: Causal graph design reviews, truncated factorization/g-formula to predict outcomes under do(A=a), guardrails for covariate logging (pre-treatment), platform integrations (PyWhy/DoWhy; custom DAG checkers).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Modularity/autonomy (interventions only change targeted mechanism), causal sufficiency or explicit latent confounding strategy, positivity in experimental allocation.

- Marketing and advertising analytics

- Use case: Estimate causal lift of campaigns (ACE, ETT) using DAG-informed covariate adjustment and potential outcomes; avoid conditioning on colliders (e.g., engagement metrics that are affected by treatment and other causes).

- Tools/workflows: Backdoor-based covariate selection; propensity modeling; g-computation; outcome modeling with doubly robust estimators.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ignorability with measured covariates, consistency about campaign “versions,” positivity across audience strata; account for interference if social spillovers are present.

- Epidemiology and public health surveillance

- Use case: Apply SUTVA checks and plan partial-interference designs in vaccine or networked settings; design data collection to represent pre-treatment covariates L and avoid uncontrolled spillovers; use truncated factorization for interventional predictions under simple causal structures.

- Tools/workflows: DAG-based data collection plans; cluster/rollout designs; g-formula for ACE; SWIGs to document potential outcomes and spillover assumptions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: SUTVA or structured interference assumptions, modularity of mechanisms, positivity, high-quality measurement of confounders.

- Machine learning model validation under distribution shift

- Use case: Use the principle of independent mechanisms (from NPSEM-IE) to prioritize invariant conditional relationships and detect spurious correlations; structure features via causal graphs to improve robustness and interpretability.

- Tools/workflows: Causal feature audits; environment-splitting strategies aligned with invariance; integration with IRM-like training and post-hoc validation; documentation via SWIGs for “what-if” interventions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Independent errors and autonomy are strong assumptions; invariance may fail under mechanism changes; faithfulness is not guaranteed—validate across environments.

- Finance and operations analytics

- Use case: Estimate causal effects of pricing or incentive policies using DAG-informed adjustment; distinguish associational shifts from interventional predictions for decision-making dashboards.

- Tools/workflows: Causal frames embedded in BI tooling; backdoor covariate selection; g-computation for do(A=a) scenarios.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ignorability, modularity (policy changes do not alter other mechanisms), positivity; careful guardrails against feedback loops that violate autonomy.

- Academic curricula and research communication

- Use case: Standardize the use of SWIGs to bridge potential outcomes and DAGs in papers and theses; require explicit assumption lists (consistency, SUTVA, ignorability, modularity, faithfulness) and g-formula derivations for interventional estimands.

- Tools/workflows: Teaching materials that map between frameworks; templated sections for assumptions and identification; reproducible code for g-formula/TMLE.

- Assumptions/dependencies: N/A beyond pedagogical context; emphasis on clear scoping (interventional vs counterfactual questions).

Long-Term Applications

The following applications require further research, scaling, instrumentation, or organizational and regulatory development before broad deployment.

- Large-scale interference and network causal inference in health and platforms

- Use case: Estimate direct and spillover effects in vaccination, social networks, and marketplaces; design policies accounting for interference and herd behavior.

- Tools/products: Interference-aware causal packages; network SWIG visualizations; cluster-randomized rollout planners.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Formal interference models, network data quality, scalable estimators; stronger assumptions than standard SUTVA; sensitivity analyses for unmeasured network confounding.

- End-to-end “CausalOps” platforms integrating DAGs, SWIGs, and estimation

- Use case: Enterprise workflows that enforce causal design reviews, graph-based data collection, automated backdoor checks, and interventional reporting (truncated factorization).

- Tools/products: Visual SWIG/DAG editors, automated assumption checklists, estimator orchestration (g-formula/IPW/TMLE), audit trails of assumptions and identifiability proofs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational adoption, culture of documenting assumptions; skilled causal analysts; standards for graph versioning and provenance.

- Decision support systems that provide interventional forecasts (do-calculus at scale)

- Use case: Healthcare and policy platforms producing “what-if” predictions under specified interventions across many variables, including joint interventions.

- Tools/products: Interventional APIs implementing truncated factorizations; domain-specific interfaces to specify do(A=a) and policy bundles; integration with simulation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Modularity/autonomy, causal sufficiency or robust handling of latent confounding; positivity across policy settings; computational scalability and governance.

- Robust causal ML for domain generalization and distribution shift

- Use case: Train models on invariant causal mechanisms rather than spurious associations; underpin safety-critical ML with causal guarantees.

- Tools/products: Causal feature selection pipelines; invariance testers; hybrid SCM–ML training loops; certification of mechanism stability.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Independent errors and autonomy are strong and often unmet; need empirical diagnostics for faithfulness and invariance; cross-domain datasets and benchmarking standards.

- Automated causal discovery paired with human-in-the-loop validation

- Use case: Propose candidate DAGs from data, then use expert review to resolve Markov-equivalent structures; attach SWIGs to define interventions and estimands.

- Tools/products: Discovery engines with constraint-based and score-based methods; ambiguity reports highlighting equivalence classes; interactive graph refinement environments.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Faithfulness or strong-faithfulness, sufficient sample sizes; domain expertise to adjudicate equivalences; risks from hidden confounders.

- Legal and regulatory frameworks around counterfactuals (necessity/sufficiency/persuasion rate)

- Use case: Standardize evidentiary use of counterfactual quantities while clarifying their stronger assumptions relative to interventional estimands.

- Tools/products: Guidance documents, forensic causal modeling templates; expert systems flagging non-identifiable counterfactuals.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Acceptance of methodological standards; careful communication of identification limits (dependence between potential outcomes is not estimable from observed data even under randomization).

- Robotics and autonomous systems planning with SCMs

- Use case: Model and manipulate mechanisms in complex systems under interventions; reason about autonomy/modularity when actuators change environment dynamics.

- Tools/products: SCM-based planners with explicit intervention modules; safety validators for mechanism changes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Autonomy/modularity may fail in closed-loop control; require instrumentation to detect mechanism drift; strong validation in real environments.

- Energy and climate policy scenario analysis

- Use case: Build causal DAGs/SCMs for grid interventions, demand response, and climate policies to forecast interventional outcomes at scale.

- Tools/products: Policy simulators with truncated factorization for multi-node interventions; SWIG documentation of causal assumptions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality causal structures, credible exogenous variables, positivity across policy ranges; handling of latent confounders and feedbacks.

- Finance: causal risk and policy optimization

- Use case: Structure causal mechanisms for regulatory stress tests and policy changes (e.g., lending criteria), moving beyond association-based risk models.

- Tools/products: Causal risk dashboards; interventional simulators for policy levers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data sufficiency, modularity of mechanisms, governance for model risk; potential conflicts with unmeasured confounding and feedback loops.

In both immediate and long-term applications, practical success depends on making assumptions explicit and testable where possible, choosing estimands carefully (interventional vs counterfactual), and building workflows that integrate graph-based reasoning (DAGs/SWIGs), structural thinking (NPSEM/SCM), and estimation methods (g-formula, IPW, doubly robust estimators), with sensitivity analysis and clear documentation as first-class components.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.