Thinking in 360°: Humanoid Visual Search in the Wild (2511.20351v2)

Abstract: Humans rely on the synergistic control of head (cephalomotor) and eye (oculomotor) to efficiently search for visual information in 360°. However, prior approaches to visual search are limited to a static image, neglecting the physical embodiment and its interaction with the 3D world. How can we develop embodied visual search agents as efficient as humans while bypassing the constraints imposed by real-world hardware? To this end, we propose humanoid visual search where a humanoid agent actively rotates its head to search for objects or paths in an immersive world represented by a 360° panoramic image. To study visual search in visually-crowded real-world scenarios, we build H* Bench, a new benchmark that moves beyond household scenes to challenging in-the-wild scenes that necessitate advanced visual-spatial reasoning capabilities, such as transportation hubs, large-scale retail spaces, urban streets, and public institutions. Our experiments first reveal that even top-tier proprietary models falter, achieving only ~30% success in object and path search. We then use post-training techniques to enhance the open-source Qwen2.5-VL, increasing its success rate by over threefold for both object search (14.83% to 47.38%) and path search (6.44% to 24.94%). Notably, the lower ceiling of path search reveals its inherent difficulty, which we attribute to the demand for sophisticated spatial commonsense. Our results not only show a promising path forward but also quantify the immense challenge that remains in building MLLM agents that can be seamlessly integrated into everyday human life.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper asks a simple question: can an AI look around and search for things in the real world the way a human does? Instead of just describing a picture, the AI should be able to “turn its head,” explore a full 360° scene, and decide where to look next to find objects (like a sign or a product) or paths (like the way to an exit). The authors build a new way to test this skill and show how to train AI to be much better at it.

What questions did the researchers ask?

They focused on five main questions:

- Can an AI actively search in a 360° environment, not just analyze a single flat image?

- How well can AI find target objects (like a specific store) and find paths (like the right direction to walk)?

- Are “in-the-wild” places (malls, subway stations, supermarkets) harder than simple household scenes?

- How much can training after the AI is built (called “post-training”) improve these skills?

- Why is finding paths harder than finding objects, and what kind of “commonsense” does the AI need?

How did they study it?

To keep things light and practical, the researchers replaced real robots and complex 3D simulators with a smart trick: use one high-quality 360° photo as the entire world. From that single panorama, the AI sees a small, normal-looking window (like the view from a phone camera) and can “rotate its head” to change where it’s looking.

The idea of 360° scenes

- Think of standing in the middle of a large space and spinning slowly to look around.

- A 360° panorama is one big image that wraps around you. The AI crops a small view from it and can turn left/right/up/down to see different parts, just like moving your head.

Two kinds of tasks

- Humanoid Object Search (HOS): Find and center a specific object, like a store sign or a product on a shelf, so a robot could reach for it next.

- Humanoid Path Search (HPS): Face in the correct direction to walk toward a destination, like “face the escalator that goes to Exit B.”

Teaching and practicing the AI

They used two training steps, explained in everyday terms:

- Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): First, they “teach by example.” The AI sees many situations with step-by-step explanations of what to do, like “Nothing useful here—turn right 45°” or “I see ‘Gate A,’ face that way.”

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): Next, they let the AI “practice” by trying actions and getting rewards when it chooses good directions. The AI learns strategies over multiple steps (like exploring first, then committing).

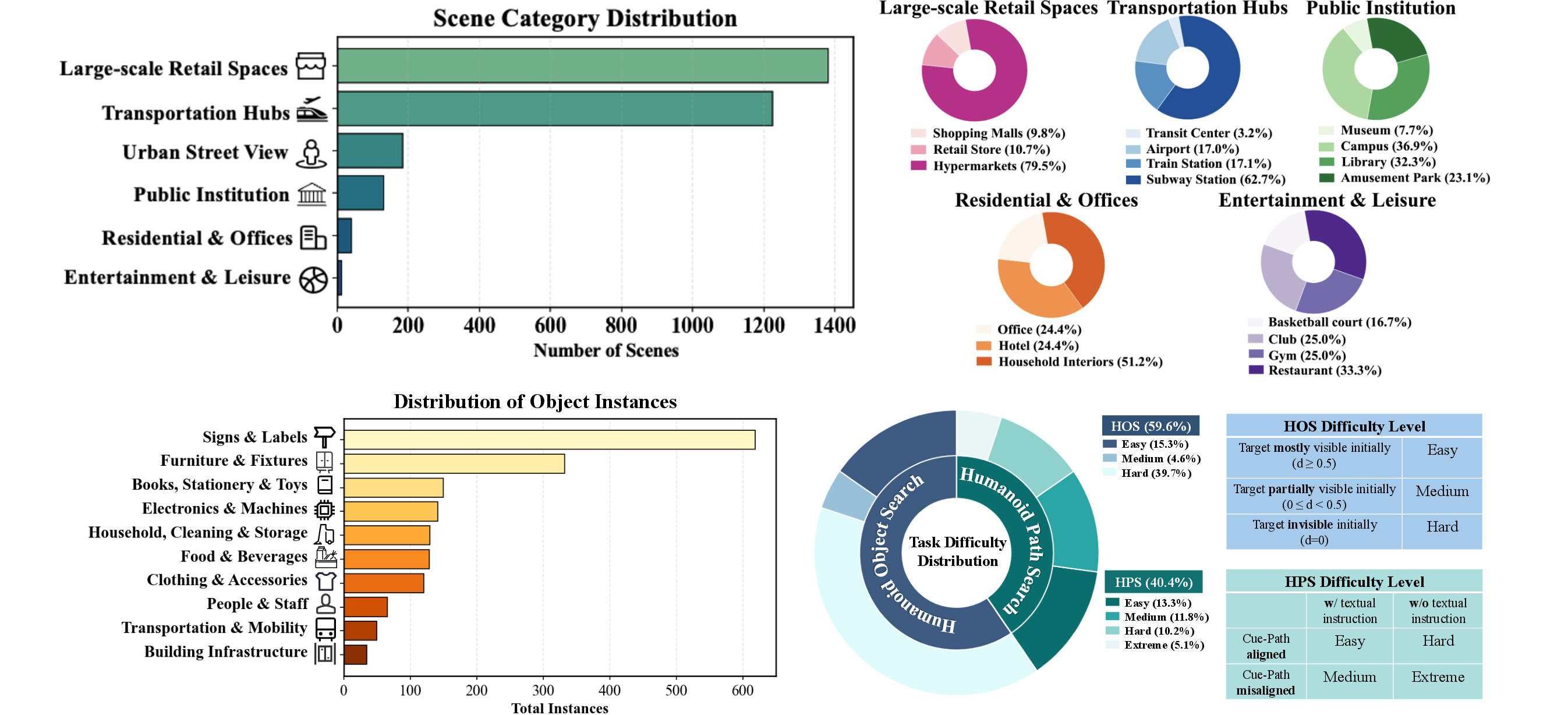

The new benchmark: H*Bench

The team built a large test set called H*Bench with about 3,000 tasks from real 360° videos and photos in cities around the world (e.g., New York, Paris, Amsterdam, Frankfurt). It includes challenging places like subway stations, shopping malls, supermarkets, libraries, museums, and busy streets.

For each scene, they wrote natural instructions (“Find Exit C,” “Face the checkout counters”), marked the correct target direction, and measured success by whether the AI’s final viewing direction was close enough to the correct one. They also labeled task difficulty (easy, medium, hard) based on how visible or misleading the clues were.

What did they find?

Here are the main results in simple terms:

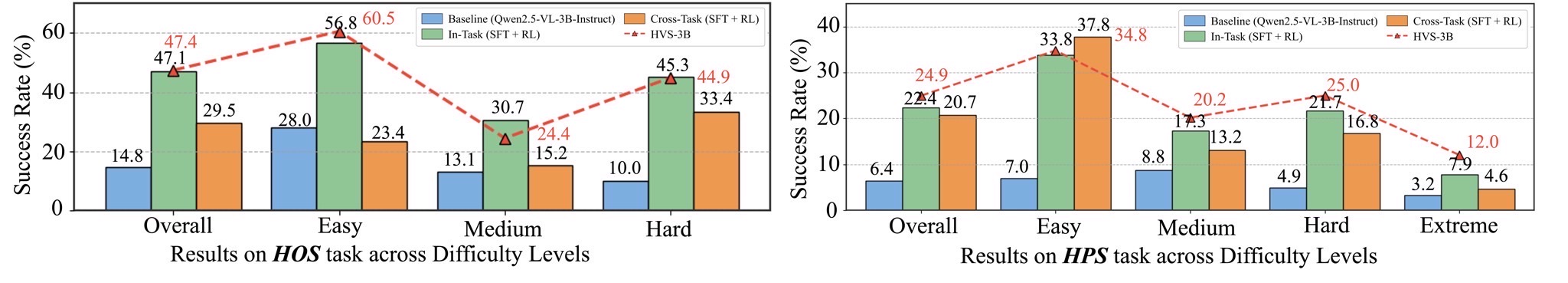

- Off-the-shelf top models struggle: Even strong proprietary models (like Gemini and GPT-4o) only succeeded around 20–33% of the time, depending on the task.

- Training helps a lot for object search: An open-source model (Qwen2.5-VL-3B) improved from about 15% to about 47% success after post-training. That’s more than triple.

- Path search is harder: The same model improved from about 6% to about 25%. Better, but still much lower than object search.

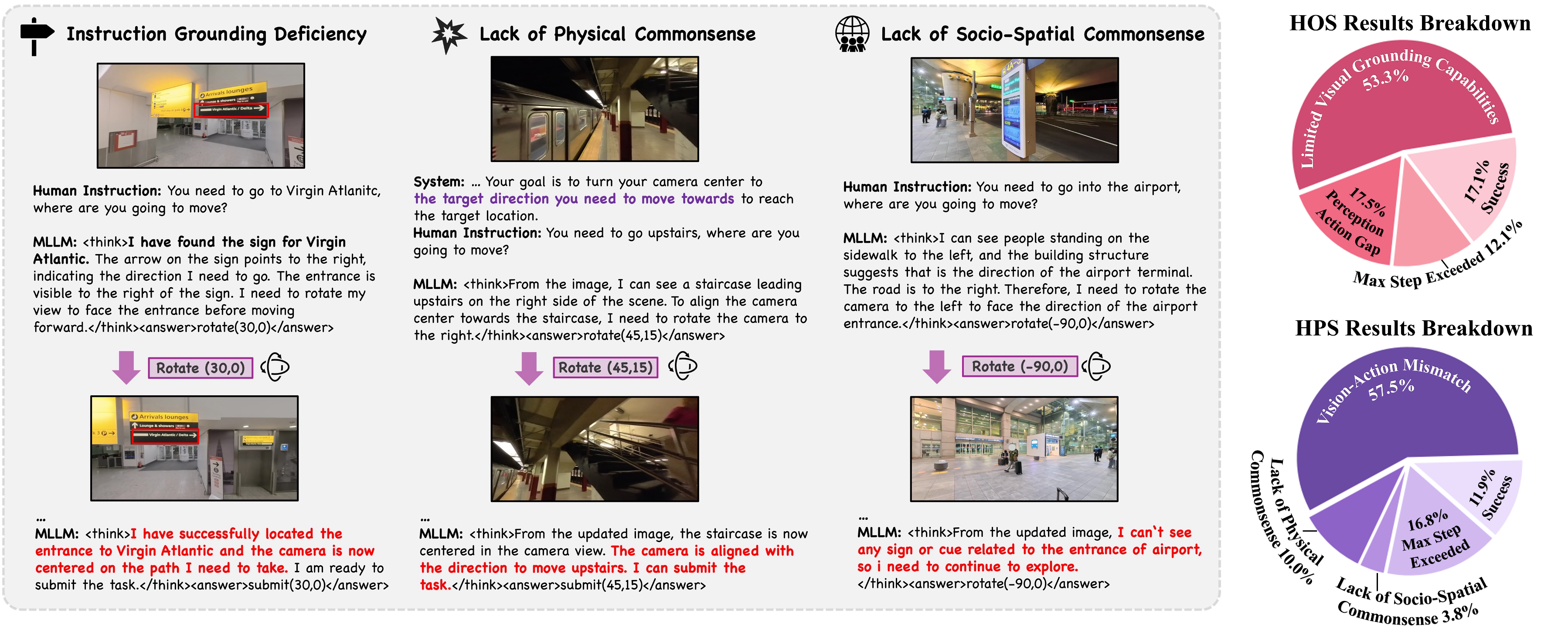

- Why is path search tougher? It demands “commonsense” about space and society:

- Physical commonsense: Don’t try to walk through walls; stairs go up/down; escalators move one way.

- Social/space rules: Signs can be misleading; entrances often have specific cues; tape or barriers mean “do not enter.”

- Active beats passive: Letting the AI actively turn and look around works better than giving it a flattened panoramic image to analyze all at once. Panoramas can be distorted, and humans naturally search by turning their heads.

- “2D-only” search isn’t enough: Methods that do great on simple 2D image search can fail badly in the embodied 360° setting. Skills learned from static pictures don’t automatically transfer to moving and acting in space.

- RL helps but can backfire on complex cases: When clues are tricky or misleading, reward-based practice can lead the AI to chase the reward rather than truly reason better, slightly hurting performance on the hardest path tasks.

Why this matters:

- Object search gains show we can make AI much better at “seeing and focusing” through training.

- Path search struggles highlight that higher-level spatial and social knowledge is still missing and needs new techniques to teach AI.

What does this mean for the future?

This work shows a practical way to study and improve “embodied” AI—the kind that doesn’t just describe the world but can act in it. Using 360° panoramas as lightweight simulators:

- Makes testing and training scalable without robots.

- Brings rich real-world complexity (crowds, clutter, multiple levels) into AI research.

Potential impact:

- More helpful robots: From store inventory robots to airport assistants, AI could look around intelligently and choose where to go next.

- Better AR assistants: Smart glasses could guide you through malls or stations by “looking” where you’re facing and pointing out the right path.

- Safer navigation: AI that understands physical constraints and social rules can avoid bad decisions (like walking into blocked areas).

What still needs work:

- Teaching true spatial and social commonsense, beyond just seeing objects.

- Designing better rewards for RL so it helps in the hardest cases.

- Building larger, more varied training data for embodied search.

- Creating models that unify 2D skills (static images) and 3D embodied skills (active exploration) without trade-offs.

In short: The paper moves AI from passive lookers to active searchers in 360° worlds and shows big progress on finding objects—but also reveals that finding paths, with real-world rules and tricky clues, remains a major challenge worth tackling next.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, concrete list of the paper’s unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions to guide future research:

- 360° panorama as a proxy for 3D: How well does a single panorama (no parallax, no occlusion resolution via translation) approximate real 3D embodied search, especially for multi-level, cluttered, or occluded scenes?

- Static scenes only: The benchmark ignores temporal dynamics (moving people, dynamic signage, lighting changes); how do agents cope with time-varying, partially occluded targets in real-world video?

- Head-only embodiment: Oculomotor (eye) control is not modeled; can explicit foveation and saccadic eye movements (with peripheral vs foveal resolution) improve efficiency and accuracy?

- No translation or body coupling: The abstraction to head rotation omits body pose, locomotion constraints, and viewpoint translation; what breaks when moving to full embodied control (head–body coordination, kinematics, IMU noise, latency)?

- Path search planar assumption: HPS evaluates only azimuth (φ) under a planar ground assumption, which conflicts with multi-level structures (ramps, stairs); how to incorporate pitch (γ), slope, and elevation changes into the task and metric?

- Path feasibility vs directionality: Success in HPS is defined by directional alignment, not by actual traversability or safety; how to evaluate affordance-aware, collision-free path intent?

- Evaluation metric narrowness: Current metric is success within a tolerance box; it does not capture search efficiency (turn count), deliberation cost, or calibration; which composite metrics (e.g., success weighted by actions, time-to-success, confidence calibration) better reflect embodied competence?

- Multiple valid solutions: The “optimal direction” is taken as bbox center, but many scenes admit multiple valid views/paths; how to score equivalence classes of correct answers and reduce penalization of alternate valid strategies?

- Reward hacking under RL: Observed degradation on harder HPS splits suggests misaligned incentives; what verified or programmatic rewards, constraints, or curricula prevent reward hacking and align optimization with true task success?

- RL scaling and credit assignment: RL was short-horizon (limited turns) and brief (e.g., 70 steps) with deterministic environments; how do longer rollouts, stochasticity, and better credit assignment affect generalization?

- Data scale and coverage: ~3k task instances may be small for open-world skills; what are the learning curves vs. dataset size, and how does performance shift with broader geographic, cultural, environmental (night, weather) diversity?

- Annotation reliability: No inter-annotator agreement or repeatability studies are reported; how stable are “optimal” directions across annotators, and how should ambiguity be represented in labels?

- GPT-4o-generated CoT for SFT: How much bias or leakage does GPT-4o introduce into the reasoning style? Do human-authored CoT, no-CoT SFT, or distilled CoT variants alter generalization?

- Toolset limitation: The agent only “rotates” and “submits”; do additional tools (OCR, detection, zoom/crop, depth estimation, semantic segmentation) materially improve performance, especially in HPS?

- Text understanding in HPS: Path difficulty depends on textual cues, yet no explicit OCR/in-the-loop evaluation is provided; how much of the HPS failure is due to text reading vs. spatial reasoning?

- Vision-token budget and resolution: The paper suggests token efficiency matters but lacks a systematic study; what are the trade-offs between resolution, token budgets, and success rates for active search?

- Baseline completeness and fairness: Comparisons omit recent video- or embodiment-focused MLLMs; decoding settings, prompt formats, and multi-image handling may be inconsistent across models—how to standardize evaluation protocols?

- Cross-task interference: Mixed training improves overall performance but can hurt some splits; which multi-task optimization (e.g., task routing, multi-objective losses, adapters) best balances object and path search?

- Memory and long-horizon reasoning: The finding that “2 rounds is enough” is reported for HOS; what context length and memory mechanisms are necessary for hard HPS cases and truly long-horizon search?

- Geometry priors: There is no explicit geometric modeling (depth, layout, topology); can integrating monocular depth, spatial graphs, or learned 3D priors close the HPS gap?

- Human upper bounds: No human performance is reported; how do humans perform (success, steps, strategies) and where exactly do models diverge from human search patterns?

- Active vs. passive confounds: The advantage of active search over panorama analysis may conflate action with distortion/tokenization differences; can controlled studies (matched resolution/token budgets, undistorted spherical processing) isolate the causal factors?

- Generalization and OOD robustness: How well do models transfer to unseen cities, camera optics, different FOVs, adverse conditions (rain/night), or truly novel scene types?

- From “decision points” to full navigation: The paper abstracts to critical head-turn decisions; how can these policies be embedded into continuous navigation stacks (localization, SLAM, trajectory generation) and assessed end-to-end?

- Sim2Real deployment: No tests on real robots/AR headsets; what domain gaps (latency, IMU drift, actuation noise, safety constraints) emerge, and how to adapt policies in the real world?

- Socio-spatial commonsense: The paper identifies missing social norms (e.g., crosswalk usage) but offers no acquisition method; which datasets, pretraining signals, or structured knowledge help internalize culture-specific conventions?

- Curriculum and difficulty shaping: Can curricula over visibility, clutter, signage alignment, and multi-level complexity improve HPS without harming HOS?

- Action space design: The effect of discretized vs. continuous rotations, adaptive step sizes, and exploration strategies is untested; what action parameterizations yield better sample efficiency and stability?

- Ethical and privacy considerations: The use of public 360° footage raises privacy questions; what protocols (blurring, consent, licensing) and benchmarks ensure ethical data collection while maintaining realism?

Glossary

- 360° panoramic image: A full-sphere image representation of an environment used to simulate immersive visual input. "represented by a 360° panoramic image."

- AGI: A form of AI aimed at general-purpose understanding and reasoning across modalities and tasks. "representing a promising pathway toward AGI."

- Azimuth: The horizontal angle specifying viewing direction around the panorama. "each defined by its azimuth () and polar angle ()."

- Back-projection: Mapping a 2D annotation (e.g., a box) from a perspective view back onto the panorama. "The bounding box is then back-projected onto the panorama"

- Bounding box: A rectangular region marking an object within an image for localization. "drawing a tight bounding box"

- Bottom-up visual saliency: A stimulus-driven process highlighting conspicuous regions for attention. "Early visual search methods use bottom-up visual saliency, top-down contextual guidance, or a combination of both"

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT): Explicit step-by-step textual reasoning produced alongside actions or answers. "structured chain-of-thought (CoT) rationales"

- Cephalomotor: Pertaining to head movement control in vision. "synergistic control of head (cephalomotor) and eye (oculomotor)"

- Disembodied: Lacking a physical agent or actions tied to the real world. "Disembodied: Lacking physical embodiment, the model cannot couple visual reasoning with actions in the physical world."

- Embodied reasoning: Reasoning that is grounded in and coordinated with physical actions and perceptions. "creating a hardware-free platform to study embodied reasoning."

- Embodied visual agent: An agent that ties visual perception to physical actions in a real or simulated environment. "developing an embodied visual agent that can actively search for information in visually crowded scenes"

- Field-of-View (FoV): The angular extent of the visual scene observed at any moment. "equipped with a limited field-of-view (FoV)"

- Fovea: The region of the retina responsible for high-acuity central vision. "capturing sharp detail only at the fovea"

- Foveal region: The central part of the visual field corresponding to the fovea’s high-acuity area. "central foveal region"

- Foveation: Directing gaze so that a target falls within the fovea for maximum visual acuity. "to mimic the human foveation"

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): A reinforcement learning algorithm variant used to optimize policies via relative performance within groups. "Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO)"

- Ground-truth actions: Verified correct actions used as labels for training or evaluation. "corresponding ground-truth actions"

- Humanoid Object Search (HOS): A task of actively locating and centrally viewing a target object for manipulation. "a.~humanoid object search (HOS): Locating and foveating a target object"

- Humanoid Path Search (HPS): A task of identifying and aligning with a navigable path toward a destination. "b.~humanoid path search (HPS): Identifying a navigable path to a destination"

- Humanoid Visual Search (HVS): The overall task framework coupling deliberate reasoning with head rotation for search. "We prototype humanoid visual search (HVS)"

- LLaMA-Factory: A framework used to implement and run supervised fine-tuning environments. "The SFT training environment is implemented with LLaMA-Factory"

- Multimodal LLMs (MLLMs): Models that understand and reason over multiple modalities such as text and images. "Multimodal LLMs can understand and reason about multiple modalities of information (e.g., text and images)"

- Oculomotor: Pertaining to eye movement control in vision. "synergistic control of head (cephalomotor) and eye (oculomotor)"

- Panoramic distortions: Geometric artifacts in panoramas that can misalign with model priors. "it avoids panoramic distortions that conflict with MLLM training priors."

- Perception–action cycle: The closed-loop process of sensing and acting where perceptions inform actions and actions change perceptions. "enabling a closed-loop perceptionâaction cycle"

- Perceptual realism: The degree to which simulated environments resemble real-world sensory experience. "often suffer from limited perceptual realism"

- Perspective view: A narrow field-of-view rendering sampled from a panorama with realistic projection. "The agent starts with a narrow perspective view"

- Planar ground geometry: An assumption that the environment’s navigable surface can be approximated as a plane. "the environment can be well approximated by a planar ground geometry."

- Polar angle: The vertical angle specifying elevation in spherical coordinates for viewing direction. "azimuth () and polar angle ()"

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): A learning paradigm where agents optimize behavior via rewards over interactions. "reinforcement learning (RL)-based post-training"

- Reward hacking: When a model exploits the reward function without genuinely solving the task. "We hypothesise that this degradation may stem from {reward hacking}"

- Reward shaping: Modifying reward signals to guide learning more effectively. "Results of GRPO with different reward shaping on ."

- Rollouts: Sequences of actions and observations sampled during training or evaluation in RL. "models trained with short GRPO rollouts"

- Saccades: Rapid eye movements used to shift gaze between points in the visual field. "by rapidly executing saccades"

- Socio-spatial commonsense: Implicit knowledge of social norms and spatial conventions in built environments. "lack of socio-spatial commonsense"

- Spherical direction: A direction specified on the sphere (by azimuth and polar angle) from a panoramic image. "the spherical direction of annotated bbox center"

- Spatiotemporal understanding: Comprehension of spatial and temporal relationships in dynamic scenes. "enhanced spatiotemporal understanding."

- Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): Training a pre-trained model on labeled data to adapt it to specific tasks. "Stage 1: Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)."

- Symbolic tool call: A structured invocation of external tools (e.g., OCR, zoom) during reasoning steps. "generate a symbolic tool call (e.g., OCR, marking, cropping, zoom in)"

- Token-efficient connector: A method to integrate high-resolution visual features into LLMs with fewer tokens. "propose a token-efficient connector to integrate high-resolution vision features with LLMs."

- Tool-augmented MLLM: An MLLM that uses external tools interleaved with reasoning to overcome modality limitations. "This is realized through a tool-augmented MLLM"

- Tolerance region: The angular bounds around the ground-truth direction within which submissions are considered correct. "falls inside a bbox-centered tolerance region"

- Unit direction vectors: Normalized 2D vectors indicating direction on the ground plane. "unit direction vectors on the ground plane"

- Vision tokenizers: Components that convert visual inputs into tokens for LLMs efficiently. "more efficient vision tokenizers"

- Vision-language navigation: Tasks where agents navigate environments guided by visual input and language instructions. "Visual navigation, along with vision-language navigation"

- Visual grounding: The ability to align textual or symbolic references to concrete visual evidence. "limited visual grounding capabilities"

- Visual navigation: Using visual inputs to move through an environment toward a goal. "Visual navigation, along with vision-language navigation, aims to develop agents that can move through an environment to reach a specified goal"

- Yaw: Rotation around the vertical axis; here, head rotation’s horizontal component. "(right/up are positive; yaw is circular)"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are practical use cases that can be deployed with the paper’s current methods and performance, especially the panorama-based “hardware-free” simulator and the post-trained HVS-3B model (SFT+RL), which achieves strong gains in Humanoid Object Search (HOS) and usable—but still limited—Humanoid Path Search (HPS).

- Panorama-powered wayfinding assistant for large venues — sectors: transportation, retail, public institutions Use a 360° camera or existing panoramic CCTV to provide “look-here-next” guidance for staff and visitors in airports, malls, libraries, museums, and subway stations. The system suggests head rotations and final viewing directions to foveate target signs (HOS) or align the body toward a corridor (HPS). Tools/products/workflows: 360° capture → perspective views → HVS agent (HVS-3B or Gemini 2.5 for higher HPS) → UI with stepwise rotation arrows and final “submit” direction. Assumptions/dependencies: Scenes are relatively static; acceptable latency; multilingual signage may need fine-tuning; path search accuracy is moderate and should be used with operator oversight to avoid misguidance.

- Retail shelf search and planogram pre-check — sector: retail Automatically locate SKUs, shelf labels, or promotional materials in cluttered aisles using HOS; provide operators a shortlist of candidate views for faster verification or stocking. Tools/products/workflows: Mobile 360° scans or fixed panoramic shelf cameras → HVS-3B for object foveation → QA dashboard for human-in-the-loop review. Assumptions/dependencies: SKU-level recognition may need additional product catalogs and OCR; occlusions and lighting variations can degrade performance; store-specific fine-tuning recommended.

- Building signage visibility audit and design review — sectors: architecture/engineering/construction (AEC), safety, policy Evaluate whether exits, information counters, or hazard signs are discoverable from practical vantage points using the paper’s visibility ratio and HOS success. Aid architects in placing wayfinding assets. Tools/products/workflows: BIM-linked 360° virtual tours → HOS tasks derived from design intents → automated “visibility score” reports → iterative design changes. Assumptions/dependencies: Requires high-quality panoramas of proposed or as-built spaces; audits reflect static snapshots; codes/standards adaptation needed for formal compliance.

- Security operations console augmentation — sector: security Assist operators in quickly orienting panoramic cameras to focus on relevant signs, entrances, or lanes; reduce time to locate reference points in visually crowded spaces. Tools/products/workflows: Panoramic CCTV feed → HOS/HPS agent overlay → click-to-rotate camera presets → operator confirmation. Assumptions/dependencies: Human oversight essential; privacy and regulatory compliance; HPS guidance should be advisory due to socio-spatial edge cases.

- Robotics telepresence: head-rotation planning for remote inspection — sector: robotics In teleoperation scenarios (maintenance, inspection), use the agent to suggest rotation sequences that efficiently “find” valves, panels, or handles before manipulation. Tools/products/workflows: 360° head/camera on robot → HVS action server integrated with ROS → operator sees stepwise rotation hints and final foveation view. Assumptions/dependencies: Adequate bandwidth; accurate panoramic calibration; tasks mostly observational (HOS outperforming HPS at present).

- Training modules for wayfinding and search — sectors: education, corporate safety Build scenario-based curricula (e.g., “find Exit A,” “locate ticket counter”) with difficulty grading and automatic scoring based on HOS/HPS criteria; useful for staff onboarding and safety drills. Tools/products/workflows: Curated panoramas → task authoring using H*Bench-like templates → LMS integration → automated success-rate analytics. Assumptions/dependencies: Requires content curation; tasks should avoid safety-critical use without supervision; cultural and language contextualization may be necessary.

- Smartphone AR “quick pano” assistant for complex indoor orientation — sector: consumer software Users capture a short panorama and receive directional hints to identify a target sign or store entrance (HOS first; HPS as advisory). Tools/products/workflows: Phone pano capture → on-device/cloud HVS inference → minimal UI showing rotational hints and highlighting target region. Assumptions/dependencies: Network and compute constraints; privacy; dynamic crowd occlusion; HPS errors in conflicting signage layouts.

- Benchmarking and post-training workflow adoption — sectors: academia, AI product teams Use H*Bench and the two-stage SFT+GRPO pipeline to evaluate and tune multimodal agents for embodied visual search. Tools/products/workflows: LLaMA-Factory (SFT), VAGEN (RL), open-weight models (e.g., Qwen2.5-VL), and proprietary baselines; active vs passive search experiments. Assumptions/dependencies: Compute resources and dataset licensing; reward design and task definitions must reflect deployment needs.

Long-Term Applications

The following use cases require further research, scaling, or development—particularly in HPS (path search), which currently lags due to missing physical, spatial, and socio-spatial commonsense and the risk of reward hacking.

- Robot navigation decision-point planner using embodied HPS — sectors: robotics, autonomous systems Deploy HPS at critical junctions to select corridors or align heading before locomotion; integrate with SLAM and motion planners. Tools/products/workflows: MLLM-augmented navigation stack → 360° situational captures at junctions → HPS “rotate then commit” → downstream motion execution. Assumptions/dependencies: Robust real-time reasoning; high success with misaligned or misleading cues; improved reward functions; safety and certification.

- Fully embodied AR navigation in dynamic environments — sectors: AR/consumer, transportation Real-time head–eye coordination for wayfinding through crowds, detours, and temporary closures; context-aware path advice respecting social norms (e.g., crosswalks, tape, stair usage). Tools/products/workflows: AR glasses with multi-camera or 360° rigs → live HPS → spatial commonsense knowledge base → multilingual sign understanding. Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy and ethics; dynamic map integration; strong latency and battery constraints; rigorous on-device inference.

- Assistive wayfinding for low-vision and neurodivergent users — sector: healthcare/accessibility Safe, stepwise embodied guidance with audio cues and environmental context (stairs, ramps, barriers). Tools/products/workflows: Wearable cameras → personalized HOS/HPS → graded confidence with fallback to human support → continuous on-device privacy controls. Assumptions/dependencies: Near-faultless path advice in safety-critical contexts; personalized models; regulatory clearance; extensive user testing.

- Facility evacuation planning and compliance auditing at scale — sectors: public safety, policy, insurance Simulate human-like search for egress routes across a large portfolio of buildings; quantify signage adequacy and path clarity under different occlusion and crowding conditions. Tools/products/workflows: Citywide 360° capture → HPS stress tests and scenario sampling → compliance dashboards → recommendations for signage redesign. Assumptions/dependencies: High fidelity to real conditions; liability and governance; frequent re-capture due to changes; standards alignment.

- Warehouse/mobile manipulation: pre-foveation and target acquisition for robot arms — sector: logistics/robotics Combine HOS with manipulation planners to reliably orient cameras toward handles, tags, or small parts before grasping. Tools/products/workflows: 360° sensing on mobile bases → active head/camera rotation via HVS → grasp planners triggered only after successful foveation. Assumptions/dependencies: Tight perception–control coupling; minimal panoramic distortion; domain-specific post-training; safety interlocks.

- Smart city CCTV: autonomous path guidance for crowd routing and incident response — sector: public sector, transportation Provide operators with adaptive routing suggestions (e.g., “direct flow to staircase B”) based on signs, barriers, and socio-spatial conventions. Tools/products/workflows: Panoramic surveillance ingest → HPS agent → operator-in-the-loop decision-making → real-time overrides. Assumptions/dependencies: Ethical use and transparency; strong accuracy and calibration; avoidance of biased crowd control; real-time verification.

- Cross-lingual signage understanding and socio-spatial commonsense learning — sectors: global deployments, tourism Enhance models to interpret multilingual signs and implicit rules across cultures (e.g., queueing patterns, entrance conventions). Tools/products/workflows: Multilingual signage datasets; synthetic RL with verified rewards; knowledge distillation into HPS. Assumptions/dependencies: Large-scale data acquisition; rights and licensing; consistent reward shaping to avoid “reward hacking.”

- Unified embodied multimodal agent (2D+3D) for physical and digital realms — sectors: software platforms, robotics A single agent that retains strong 2D visual search (e.g., on V*Bench) while mastering 3D embodied search (H*Bench), with token-efficient visual connectors and video grounding. Tools/products/workflows: Video-centric pretraining; improved connectors; large-scale embodied data collection; better verifiable rewards. Assumptions/dependencies: Significant compute; comprehensive benchmarks; robust evaluation for higher-order spatial reasoning; sustained community effort.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Data availability and capture: High-quality 360° panoramas (or multi-camera rigs) are required; dynamic changes, occlusions, and crowding degrade performance.

- Model reliability and safety: HOS is immediately strong; HPS still needs advances in physical, spatial, and socio-spatial commonsense, plus reward designs that avoid reward hacking.

- Integration constraints: Real-time inference, latency, battery, bandwidth, and privacy regulations affect feasibility in live deployments.

- Human-in-the-loop: For safety-critical or public-facing tasks, operator oversight is essential until path search performance reaches dependable thresholds.

- Localization and language: Multilingual signage and local conventions often require domain-specific fine-tuning and curated data.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.