Deterministic Inference across Tensor Parallel Sizes That Eliminates Training-Inference Mismatch (2511.17826v1)

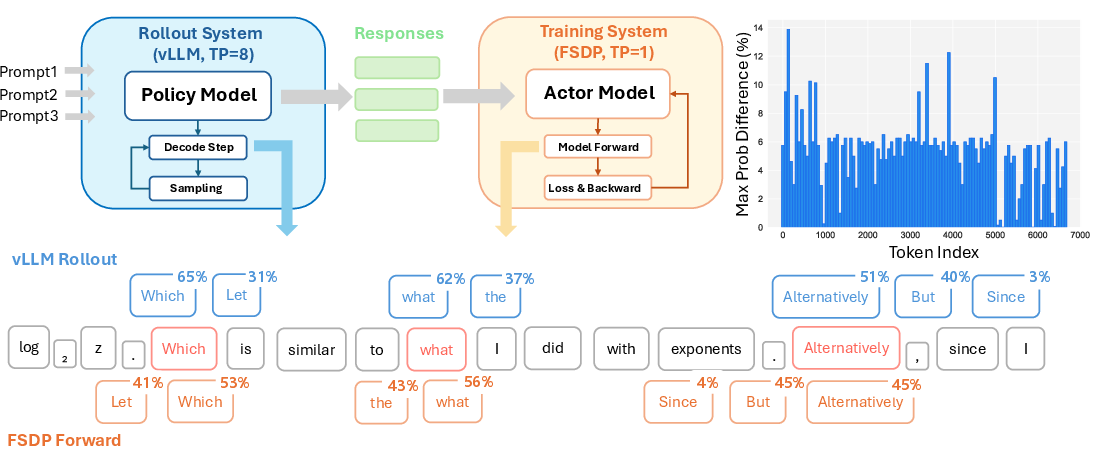

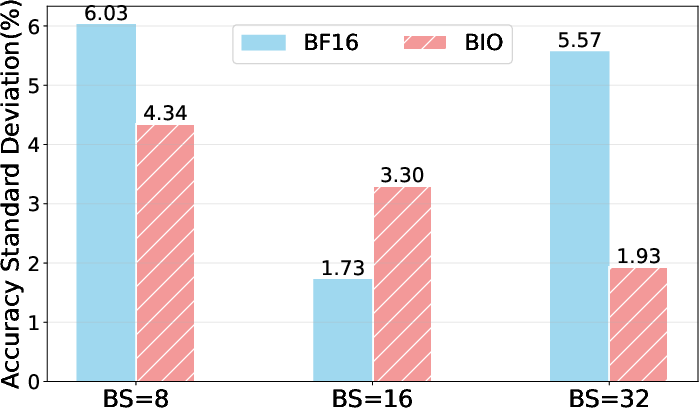

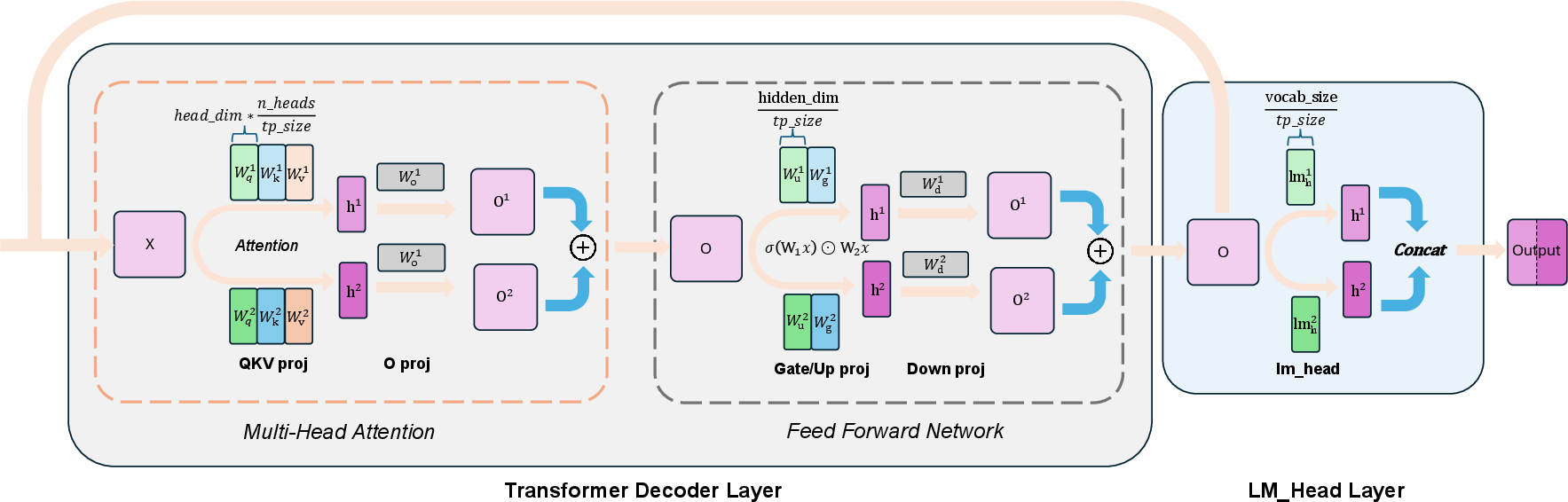

Abstract: Deterministic inference is increasingly critical for LLM applications such as LLM-as-a-judge evaluation, multi-agent systems, and Reinforcement Learning (RL). However, existing LLM serving frameworks exhibit non-deterministic behavior: identical inputs can yield different outputs when system configurations (e.g., tensor parallel (TP) size, batch size) vary, even under greedy decoding. This arises from the non-associativity of floating-point arithmetic and inconsistent reduction orders across GPUs. While prior work has addressed batch-size-related nondeterminism through batch-invariant kernels, determinism across different TP sizes remains an open problem, particularly in RL settings, where the training engine typically uses Fully Sharded Data Parallel (i.e., TP = 1) while the rollout engine relies on multi-GPU TP to maximize the inference throughput, creating a natural mismatch between the two. This precision mismatch problem may lead to suboptimal performance or even collapse for RL training. We identify and analyze the root causes of TP-induced inconsistency and propose Tree-Based Invariant Kernels (TBIK), a set of TP-invariant matrix multiplication and reduction primitives that guarantee bit-wise identical results regardless of TP size. Our key insight is to align intra- and inter-GPU reduction orders through a unified hierarchical binary tree structure. We implement these kernels in Triton and integrate them into vLLM and FSDP. Experiments confirm zero probability divergence and bit-wise reproducibility for deterministic inference across different TP sizes. Also, we achieve bit-wise identical results between vLLM and FSDP in RL training pipelines with different parallel strategy. Code is available at https://github.com/nanomaoli/llm_reproducibility.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about making LLMs give the exact same answers every time, even when they are run on different numbers of GPUs or in different systems. The authors show why LLMs can produce slightly different results (even with the same input and the same “no randomness” settings), and they introduce a new method called Tree-Based Invariant Kernels (TBIK) that makes the results fully deterministic—meaning bit-for-bit identical—across different setups.

What questions did the researchers ask?

The paper asks three simple questions:

- Why do LLMs sometimes produce different outputs when the system settings change (like the number of GPUs used)?

- Can we make LLM outputs exactly the same, no matter how many GPUs or which system is used?

- Will this fix help important use cases like reinforcement learning (RL), where small differences can break training?

How did they approach it?

Everyday analogy: adding numbers in different orders

Computers handle decimals and big numbers with limited precision. That means tiny rounding happens. Imagine adding a long list of very small numbers. If you add them left-to-right you might get slightly different results than if you add them in a different order. That’s called “non-associativity.” It’s like measuring sand with a small cup—every scoop is close, but tiny differences pile up. If the order of scoops changes, the final pile can be a tiny bit off.

In LLMs, calculations are spread across many GPUs. Each GPU does part of the work, and then all the partial results are added together. If the number of GPUs changes or the way they share results changes, the order of those additions changes—so the final answer can be slightly different.

What they built and changed

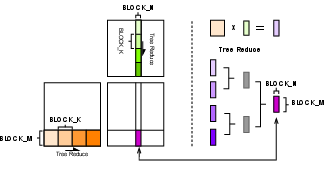

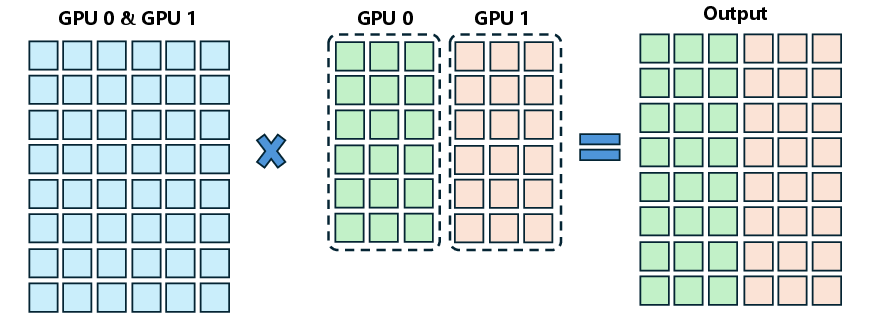

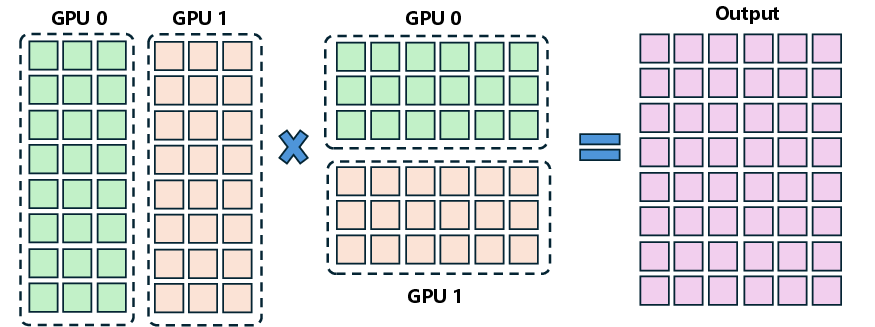

The authors designed special math “kernels” (the low-level code that runs on GPUs) that force all additions to happen in the same fixed pattern, like a tournament bracket where winners combine in a set order. They:

- Used a binary tree structure for adding numbers both inside each GPU and across all GPUs. Think of it as pairing results, adding them, then pairing those sums and adding again, and so on—always in the same shape and order.

- Aligned the local math (inside a single GPU) with the global math (across GPUs) so the overall order of operations is identical no matter how many GPUs you use.

- Implemented these kernels with Triton (a tool for GPU programming) and integrated them into popular systems: vLLM (often used for fast inference) and FSDP (Fully Sharded Data Parallel, often used for training).

- Ensured other parts of the model (like attention and normalization layers) use consistent, batch-invariant versions and identical settings in both systems, so there are no hidden differences.

What did they find and why it matters?

Here are the main results:

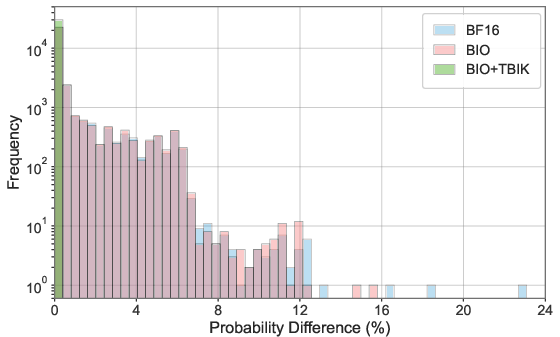

- Deterministic outputs across different GPU counts: With TBIK, the model produces exactly the same outputs—bit by bit—even when changing the tensor parallel (TP) size from 1, 2, 4, to 8 GPUs.

- Zero probability divergence: The probabilities the model assigns to next-token choices are identical across setups. That’s a stricter guarantee than just matching final text—it proves the entire calculation is aligned.

- Consistency across frameworks: They matched results between vLLM (used for generating responses) and FSDP (used for training), even when one uses multiple GPUs and the other uses one. This removes a big source of mismatch in RL pipelines.

- Real-world impact on evaluation: Without their method, accuracy on tests like AIME can vary just by changing system settings—meaning your score might swing for reasons unrelated to the model. With TBIK, evaluation becomes fair and reproducible.

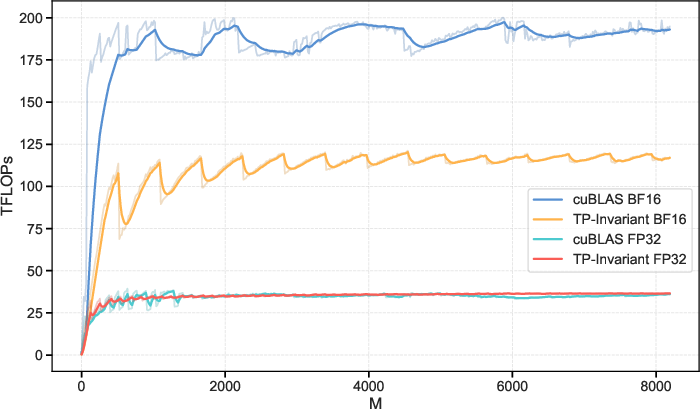

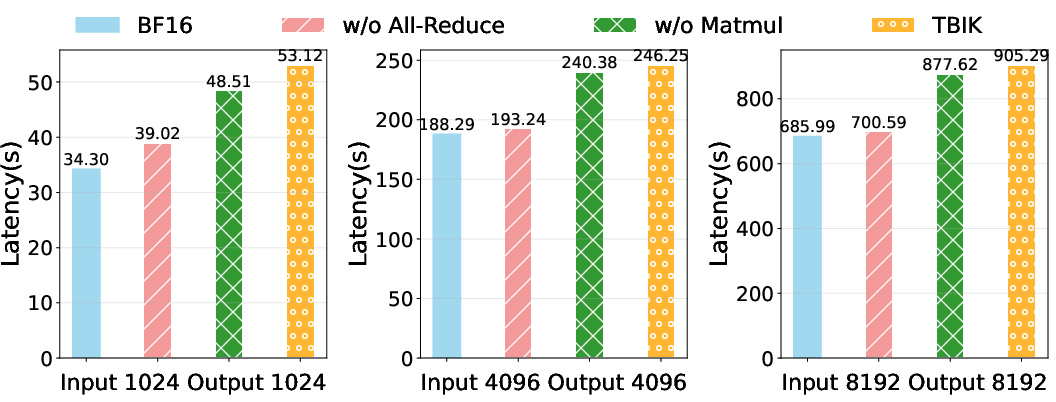

- Trade-off: The deterministic method introduces extra computation and communication steps, so it’s slower than the fastest non-deterministic mode. However, the slowdown is acceptable for situations where reproducibility is required.

Why this matters:

- In RL with LLMs, training often uses one system and rollout (generating data) uses another. If these systems produce slightly different probabilities, training can become unstable or “off-policy,” which harms learning. TBIK fixes this by making both sides match exactly.

- In multi-agent scenarios or when an LLM acts as a judge, you need consistent behavior for fair comparisons and reliable debugging. TBIK gives that consistency.

What is the impact?

This research makes LLMs reliably reproducible across different GPU setups and frameworks. That means:

- Fairer model evaluation: Scores won’t change just because you ran the model differently.

- More stable RL training: Training and rollout engines match exactly, supporting truly on-policy learning.

- Easier debugging and collaboration: Multi-agent systems and complex pipelines behave consistently, so it’s simpler to find and fix issues.

Looking ahead, the authors plan to extend this to low-bit (quantized) models, which use even trickier math with rounding and scaling. If they can bring the same tree-based determinism to those models, the benefits will cover an even larger part of modern LLM deployments.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper.

- Formal generalization of the TP-invariance proof to arbitrary TP sizes (non-power-of-two C), uneven K-dimension tiling, and non-power-of-two tile counts N; current theorem assumes evenly partitioned sequences and C=2t.

- Deterministic handling of remainder tiles and irregular shapes (e.g., K not divisible by C×Block_K), beyond the ad-hoc K_first workaround; a rigorous correctness and invariance proof for all shape edge cases.

- End-to-end determinism under realistic serving features (continuous batching, prefix caching, chunked prefill, streaming generation, variable-length requests); current experiments disable several production optimizations and do not assess their interaction with TBIK.

- RNG alignment across frameworks and TP sizes under random sampling: guaranteeing identical RNG consumption order and seeding across dynamic batching, variable-length sequences, and multi-request pipelines (beyond probability matching).

- Deterministic decoding with KV-cache updates and incremental attention paths (decode-side kernels): verified support and performance under typical vLLM decode settings, not just prefill-only alignment.

- Multi-node scalability and topology robustness: deterministic guarantees and performance on NVLink, PCIe, and InfiniBand across nodes, with NCCL/UCX collectives and realistic stream scheduling, contention, and overlap.

- Integration with vendor collective libraries: a deterministic, high-performance All-Reduce (tree or otherwise) implemented via NCCL/ROCm that preserves order under asynchronous streams, overlapping compute-communication, and heterogeneous interconnects.

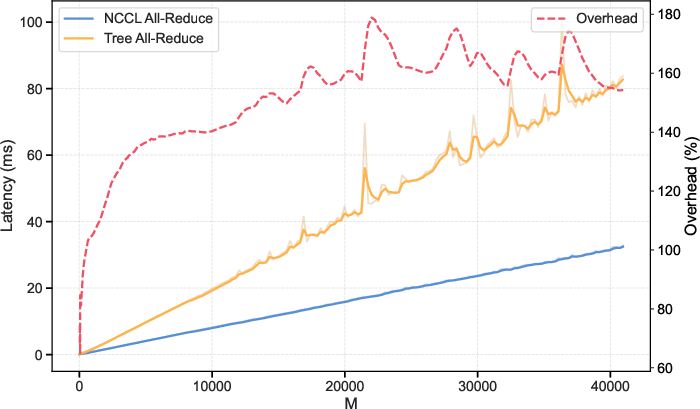

- Performance optimization of TBIK: reducing 56–135% end-to-end latency overhead via kernel tuning (block sizes, warp specialization, register/shared-memory usage), deterministic collective optimizations, and communication overlap; providing a systematic performance–determinism trade-off analysis.

- Memory footprint analysis of tree accumulators (S buffers) and counters: quantifying extra workspace requirements, register pressure, occupancy impacts, cache behavior, and fragmentation with PagedAttention, plus mitigation strategies.

- Numerical accuracy implications: error bounds and empirical comparisons of tree-reduction vs cuBLAS accumulation orders (FP16/BF16/FP32), assessing any accuracy drift relative to widely used baselines.

- Applicability to MoE architectures: deterministic expert routing (Softmax + Top-k) under slight numeric variations, tie-breaking policies, cross-device consistency, and evaluation on MoE models (e.g., Qwen3-MoE, Switch-Transformer).

- Deterministic low-bit inference (FP8/INT8/INT4): a tree-consistent low-bit GEMM (including rounding, scaling, fused dequant paths), with proofs and performance evaluation across quantization schemes (GPTQ, AWQ, KIVI).

- Cross-architecture portability: correctness and performance on Hopper/Blackwell (wgmma), Ada vs Hopper differences, and non-NVIDIA platforms (AMD ROCm, Intel GPUs), including deterministic instruction-level semantics and kernel mappings.

- Compatibility with additional parallel strategies: sequence parallelism (SP), ZeRO variants, pipeline parallelism with overlapping stages, and tensor+sequence hybrid sharding; verifying determinism under combined parallelisms.

- Deterministic attention variants: coverage for FlashAttention 2/3, MQA/GQA, cross-attention, long-context mechanisms, and fused kernels—ensuring fixed reduction/topology and hyperparameters across frameworks.

- Real-world RL benefits: rigorous end-to-end on-policy RL experiments showing improved stability, convergence, and sample efficiency (beyond four AIME prompts), including diverse tasks, longer training runs, and MoE policies.

- Broader framework coverage and reproducibility: integration and validation with SGLang, TensorRT-LLM, Megatron-LM, and standard training stacks beyond FSDP, with documented API-level policies for deterministic kernel selection and hyperparameter locking.

- Deterministic tie-handling in argmax/top-k selections (e.g., equal logits) and stable sorting semantics across devices/frameworks to prevent nondeterministic branch behaviors.

- Operational guidance and diagnostics: automated detection of determinism-breaking configurations (kernel variants, hyperparameters, topology), reproducibility checkers, and standardized determinism profiles for deployment.

Glossary

- AIME24: A benchmark dataset based on the 2024 American Invitational Mathematics Examination used to evaluate reasoning in LLMs. Example: "We run the same prompt from AIME24 dataset across varying TP sizes (1/2/4/8)"

- All-Gather: A collective communication primitive that gathers data from all processes to all processes. Example: "we synchronize the per-GPU partial results using an all-gather collective operation."

- All-Reduce: A collective operation that reduces values (e.g., sums) across processes and broadcasts the result back to all. Example: "must then be summed together through an All-Reduce operation."

- Batch-Invariant Operations (BIO): Kernel designs that ensure results are independent of batch size by fixing reduction orders per example. Example: "introduced batch-invariant operations (BIO), including batch-invariant FlexAttention, RMSNorm, and MatMul kernels, which guarantees that inference results remain deterministic regardless of batch sizes."

- BF16: Brain floating point 16-bit format used to accelerate training/inference while retaining FP32-like dynamic range for accumulations. Example: "vanilla BF16 inference"

- Binary-tree reduction: A hierarchical reduction scheme that combines partial results via a fixed binary tree to ensure consistent accumulation order. Example: "the same binary-tree topology"

- Column-parallel: A tensor parallel sharding strategy that splits weight matrices along the output (column) dimension so outputs can be concatenated without reduction. Example: "the QKV proj, gate proj, up proj, and lm head layers are column-parallel"

- Continuous batching: Dynamically changing batch composition during serving to improve utilization, which can affect numerical order of operations. Example: "continuous batching \cite{yu2022orca} which dynamically changes the set of requests in a batch"

- CUDA Graph: A CUDA feature to capture and replay GPU workloads with reduced launch overhead. Example: "with CUDA Graph and Prefix Caching disabled."

- cuBLAS: NVIDIA’s CUDA Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms library for high-performance GPU BLAS routines. Example: "the cuBLAS GEMM with NCCL Ring Reduce"

- Data Parallelism (DP): A parallel strategy that replicates the model across GPUs and shards the batch across devices. Example: "Data Parallelism (DP)."

- Decode phase: The generation stage of autoregressive inference where tokens are produced step by step. Example: "the prefill and decode phases to use the same attention kernel."

- Deterministic inference: Inference that produces identical outputs for identical inputs across runs and configurations. Example: "Deterministic inference is increasingly critical for LLM applications"

- FMA (Fused Multiply-Add): An arithmetic operation that performs a multiplication and an addition with a single rounding to reduce numerical error. Example: "Fused Multiply-Add (FMA) \cite{NVIDIA_FloatingPoint_CUDA} is used to compute with an exact double-length product, followed by an addition with a single rounding."

- FlashAttention: A memory-efficient attention algorithm optimized for GPUs via tiling and recomputation. Example: "the block size for MatMul and Flash-Attention"

- FlexAttention: A configurable attention kernel that can be made batch-invariant to reduce nondeterminism. Example: "batch-invariant FlexAttention"

- FSDP (Fully Sharded Data Parallel): A training approach that shards model parameters, gradients, and optimizer states across devices. Example: "Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP)~\cite{fsdp}"

- GEMM: General Matrix Multiply, the core building block for dense linear algebra on GPUs/CPUs. Example: "cuBLAS GEMM"

- Greedy decoding: Decoding strategy that always selects the highest-probability token at each step. Example: "Even with greedy decoding"

- IEEE 754: The standard for floating-point arithmetic specifying formats and rounding behavior. Example: "IEEE 754 floating point operations"

- LayerNorm: A normalization technique that normalizes across the features of a layer to stabilize training. Example: "Other commonly used operations like Softmax, LayerNorm, RMSNorm, and RoPE"

- LLM-as-a-judge: Using an LLM to evaluate outputs of other models or systems. Example: "Evaluation with LLM-as-a-judge"

- Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): A model architecture that routes tokens to specialized expert subnetworks to improve capacity and efficiency. Example: "Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models"

- NCCL: NVIDIA Collective Communications Library for multi-GPU/multi-node communication primitives. Example: "In NCCL, users can specify node topology"

- Non-associativity: Property where the grouping of floating-point operations affects results due to rounding. Example: "non-associativity of floating-point arithmetic"

- Non-Split-K: A GEMM strategy that avoids splitting the reduction (K) dimension, thereby avoiding extra partial-sum reductions. Example: "Split-K versus Non-Split-K Matmul"

- Off-policy RL: Reinforcement learning where the behavior policy generating data differs from the target policy being optimized. Example: "behave more like off-policy"

- Pipeline Parallelism (PP): A strategy that partitions model layers across devices and pipelines microbatches through them. Example: "Pipeline Parallelism (PP)."

- Prefix Caching: Caching of key/value or intermediate states for shared prefixes to speed up repeated prompts. Example: "with CUDA Graph and Prefix Caching disabled."

- REINFORCE: A policy gradient algorithm that updates parameters using sampled returns and log-probability gradients. Example: "we use the REINFORCE algorithm as an example"

- Ring Reduce: A reduction algorithm that circulates data around devices in a ring for aggregation. Example: "NCCL Ring Reduce"

- RMSNorm: Root Mean Square Layer Normalization variant that normalizes by RMS without mean-centering. Example: "RMSNorm"

- RoPE: Rotary Positional Embeddings, a technique for encoding token positions via complex rotations. Example: "RoPE"

- Row-parallel: A tensor parallel sharding strategy that splits inputs/weights along the K dimension and requires cross-device reductions. Example: "the o proj and down proj layers are row-parallel."

- SGLang: A serving framework for LLM inference. Example: "vLLM and SGLang~\cite{sglang}"

- SiLU: Sigmoid Linear Unit activation function used in transformer feed-forward networks. Example: "SiLU activation"

- Split-K: A GEMM technique that splits the reduction dimension K across threads/blocks and merges partial sums. Example: "Split-K versus Non-Split-K Matmul"

- Tensor Parallelism (TP): Model parallelism that shards tensors (e.g., weights) across devices to scale compute. Example: "Tensor Parallelism (TP)."

- Triton: A GPU programming language and compiler for custom high-performance kernels. Example: "We implement these kernels in Triton"

- TritonAttention: An attention kernel implementation in Triton used for deterministic/batch-invariant setups. Example: "prefill-only TritonAttention"

- Tree All-Reduce: An all-reduce variant that aggregates values via a tree topology for consistent reduction order. Example: "Inter-GPU Reduction with Tree All-Reduce."

- Tree-Based Invariant Kernels (TBIK): Proposed kernels that enforce a tree-structured reduction order to ensure TP-invariant determinism. Example: "Tree-Based Invariant Kernels (TBIK)"

- vLLM: An LLM serving framework optimized for high-throughput, low-latency inference. Example: "vLLM"

- WGMMA: Warp-Group Matrix Multiply-Accumulate instruction available on NVIDIA Hopper GPUs. Example: "wgmma on Hopper"

- Warp specialization: Kernel optimization technique that assigns distinct roles to warps to improve performance. Example: "and warp specialization"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are practical, deployable use cases that can be built today on top of the paper’s Tree-Based Invariant Kernels (TBIK) and batch-invariant operations (BIO), with clear sector links, potential tools/workflows, and feasibility notes.

- Deterministic on-policy RL training and evaluation

- Sector: software, robotics, education, gaming

- What: Ensure the rollout engine (e.g., vLLM with TP>1) and learner (e.g., FSDP with TP=1) compute identical token probabilities/logits, preventing off-policy drift caused by tensor-parallel mismatches.

- Tools/workflows: “Deterministic mode” for RLHF/PPO/DPO pipelines; probability-gap monitors; parity tests between serving and training; CI gate enforcing zero probability divergence.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires integrating TBIK into row-parallel layers, using identical attention kernels and hyperparameters across stacks, fixed seeds, and a tree-based All-Reduce. Performance overhead (56–135% vs. vanilla BF16) must be budgeted.

- Reproducible LLM-as-a-judge evaluation

- Sector: academia, competitions, education platforms

- What: Run contest grading, peer-review scoring, and leaderboard evaluations with outputs that are bit-wise identical across TP sizes, batch sizes, and serving frameworks.

- Tools/workflows: Add a “deterministic evaluation” toggle to lm-eval, vLLM/SGLang-based judges; store exact seeds and kernel configs in evaluation metadata.

- Assumptions/dependencies: BIO+TBIK must be used end-to-end; disables some throughput-oriented features (e.g., chunked prefill); requires kernel/hyperparameter alignment.

- Debuggable multi-agent systems with reproducible trajectories

- Sector: software, robotics, autonomous systems

- What: Guarantee identical agent interactions across runs and hardware by eliminating TP-related nondeterminism, making failures and emergent behaviors precisely debuggable.

- Tools/workflows: Deterministic agent orchestration mode; reproducibility-aware tracing; agent-level state replay using identical seeds and configurations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Same weights, seeds, kernels, and reduction topology; tolerate latency overhead for debug runs; heterogeneous GPUs supported in paper’s tests (L40S, RTX 6000), but broader hardware coverage should be validated.

- Production scaling without behavioral drift

- Sector: cloud, MLOps, devops

- What: Scale inference from TP=1 to TP=4/8 (or reconfigure batch sizes) without altering outputs, enabling safe canary deployments, rollbacks, and autoscaling.

- Tools/workflows: “Deterministic serving tier”; config-locked workloads; output hash monitoring; deterministic All-Reduce in clusters.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Tree All-Reduce must be available; TP sizes commonly power-of-two are best supported; performance impacts and network topology (e.g., NVLink) influence cost.

- Stable Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) routing

- Sector: model providers, large-scale inference

- What: Prevent expert-selection instability under tiny numeric perturbations; ensure identical router decisions across TP changes.

- Tools/workflows: Apply TBIK to row-parallel layers and ensure deterministic softmax/normalization in router; MoE “deterministic mode.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Router kernels and their hyperparameters must be aligned; pay the overhead trade-off; comprehensive coverage of all MoE ops is required.

- Auditable decisions for compliance-sensitive workloads

- Sector: finance, healthcare, content moderation

- What: Provide bit-wise reproducible outputs for compliance checks, moderation decisions, risk controls, and audit trails across scaling events and hardware swaps.

- Tools/workflows: “Audit-grade inference mode”; persisted seeds/configs; deterministic logs; parity tests when migrating infrastructure.

- Assumptions/dependencies: BIO+TBIK must be consistently applied; throughput reductions may require dedicated “deterministic pools.”

- Fair, replicable academic benchmarking and ablations

- Sector: academia, open-source

- What: Run ablations and benchmark submissions where greedy/sampled outputs do not change under TP/batch variations, controlling a major confounder in LLM research.

- Tools/workflows: Reproducibility badges; evaluation manifests recording seeds and kernel configs; zero-divergence checks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires adopting deterministic kernels across the stack; sampling still needs fixed seeds to be comparable.

- Cross-framework parity testing (serving vs. training)

- Sector: software, ML infrastructure

- What: Continuous parity checks that guarantee vLLM and FSDP produce bit-wise identical probabilities for the same model/config, preventing silent deployment regressions.

- Tools/workflows: Parity harness comparing logits/probabilities per token; thresholded alerting (target: 0 divergence); pipeline integration in CI/CD.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Identical kernels and hyperparameters across frameworks; BIO+TBIK integrated; seed consistency.

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities require further research, engineering, or ecosystem adoption (e.g., low-bit kernels, vendor integration, standardization). They build on the paper’s methods and insights.

- Deterministic low-bit (quantized) inference

- Sector: edge, cost-optimized cloud, energy

- What: Extend TBIK to AWQ/GPTQ/FP8/INT4 GEMMs with tree-consistent dequantization/rounding to achieve bit-wise invariance at lower precision/cost.

- Tools/products: “Deterministic low-bit GEMM” libraries; quantization strategies aligned to tree reduction paths.

- Dependencies: Nontrivial co-design of rounding/scaling and fused ops; vendor toolchain support; maintaining efficiency under determinism.

- Standardization and policy for deterministic LLM inference

- Sector: policy, accreditation, public sector procurement

- What: Define and adopt a “deterministic inference” standard for evaluations, audits, and public benchmarks (e.g., require zero probability divergence across TP configs).

- Tools/products: Reproducibility certification; standard manifests recording seeds/hyperparameters/topologies; compliance checkers.

- Dependencies: Community and platform adoption; clear test suites; cost trade-offs acceptable in regulated contexts.

- Vendor-level integration (NCCL/cuBLAS/Triton)

- Sector: GPU vendors, systems software

- What: Ship a high-performance, tree-consistent All-Reduce and GEMM in mainstream libraries with tunable determinism/performance knobs.

- Tools/products: “Deterministic All-Reduce” in NCCL; tree-based GEMM in cuBLAS; Triton templates; hardware-aware topology optimization.

- Dependencies: Engineering to recover performance (warp specialization, block size tuning, NVLink-aware collectives); kernel coverage expansion.

- Deterministic cloud SLAs and service tiers

- Sector: cloud providers, platform-as-a-service

- What: Offer a determinism SLA tier for enterprises needing reproducible results across scaling events and hardware heterogeneity.

- Tools/products: Managed “Deterministic Mode” endpoints; configuration locks; deterministic topology orchestration; parity monitors.

- Dependencies: Performance overhead must be priced; network topology-aware collectives (e.g., tree over rings); operational playbooks.

- Safety-critical autonomous and robotic decision logging

- Sector: robotics, automotive, industrial control

- What: Guarantee decisions are replayable and identical across runs for post-incident analysis, certification, and safety auditing when LLMs are in-the-loop.

- Tools/products: Deterministic inference pipelines with traceable seeds; replay tooling; certified deterministic kernels.

- Dependencies: Broader hardware coverage; end-to-end kernel coverage beyond transformers; regulatory alignment.

- Deterministic educational auto-grading and testing

- Sector: education, assessment

- What: Eliminate grader drift across hardware and scaling; ensure identical feedback and scores for identical submissions.

- Tools/products: Deterministic judge services; reproducible evaluation manifests; auditing workflows.

- Dependencies: Institutional adoption; managing throughput overhead during exam peaks.

- Federated/edge reproducibility across heterogeneous devices

- Sector: mobile, IoT, embedded

- What: Cross-device identical outputs under different parallelization and numeric kernels, enabling consistent experiences and auditability at the edge.

- Tools/products: Portable deterministic kernels across GPU/CPU/NPU; topology-agnostic tree reductions; config synchronization protocols.

- Dependencies: Hardware-specific kernel support; quantized deterministic ops; communication-efficient collectives.

- Deterministic multi-agent simulation platforms

- Sector: gaming, research simulation

- What: Replicable environment dynamics, identical agent trajectories for controlled experimentation and tournament fairness.

- Tools/products: Deterministic simulation runtimes; scenario replay tooling; zero-divergence checks in orchestration layers.

- Dependencies: Wider kernel coverage (tokenizers, sampling variants); integration with agent frameworks.

- Performance-optimized TBIK for production-scale workloads

- Sector: cloud inference, LLM providers

- What: Close the performance gap via better tree kernels and All-Reduce (e.g., warp specialization, block tuning, NVLink-aware collectives), making determinism viable at scale.

- Tools/products: Optimized deterministic GEMM/All-Reduce; topology-aware schedulers; auto-tuners balancing determinism vs. performance.

- Dependencies: Kernel engineering; network and hardware co-design; auto-tuning research.

- Deterministic MoE training at massive scale

- Sector: frontier model training

- What: Stable expert routing and reproducible gradients across TP variations; eliminate hidden nondeterminism that destabilizes large MoE runs.

- Tools/products: Deterministic router kernels; aligned normalization/softmax; parity monitors for expert selection.

- Dependencies: Full coverage of all MoE ops; integration with quantized layers; handling mixed-precision edges.

- Diagnostic toolchains for determinism

- Sector: ML tooling

- What: Tools that analyze, visualize, and “diff” reduction orders and numeric paths across stacks to identify nondeterministic hotspots.

- Tools/products: Determinism profilers; topology diff viewers; automated remediation advice (e.g., kernel/hyperparameter locks).

- Dependencies: Visibility into kernels and collectives; standardized metadata schema.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Determinism hinges on using identical kernels, hyperparameters (e.g., block sizes), random seeds, and reduction topologies across environments.

- Tree-based All-Reduce and tree-consistent MatMul must be used for row-parallel layers; column-parallel layers rely on BIO.

- TP sizes that are powers of two are best supported by the theoretical guarantees; non-power-of-two cases require careful tile-depth handling.

- Some throughput-oriented features (e.g., chunked prefill, certain continuous batching behaviors) may need to be disabled or aligned to keep determinism.

- Performance overhead is nontrivial today; network topology (e.g., NVLink vs. PCIe) and optimized collectives materially affect feasibility and cost.

- Quantized/low-bit kernels are not yet covered; extending determinism to these is an acknowledged, important future direction.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.