The Physics of Black Holes and Their Environments: Consequences for Gravitational Wave Science (2511.14841v1)

Abstract: Ten short years ago, we had the rare privilege of witnessing the onset of a renaissance in science: humanity finally succeeded in its arduous quest to directly detect gravitational waves. This breakthrough did not occur in a vacuum: it was the natural culmination of decades of research dedicated towards understanding the nature of gravitation based on Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. It is a story of false starts, perseverance, and remarkable insights, propelled as much by technological progress as by human curiosity. We now proudly live in the new golden age of gravitational physics. The detection of gravitational wave signals from the merger of binary black holes and neutron stars are becoming routine. Coupled with our theoretical understanding of phenomena in the strong gravity regime, black hole physics has become a precision science. The purpose of these lecture notes is to help the reader understand the language and framework of this rapidly evolving subject, and to develop the ability to interpret, think, and discuss ideas that lie at the confluence of gravitational wave astronomy and black hole physics. It is our hope that these notes will prepare students and colleagues for the next revolution when gravitational wave events become commonplace and we begin to observe unexpected features in the signal, indicating either surprising astrophysical scenarios or a strong need to modify the theoretical description of gravitational interactions. We provide first principles analysis of black hole and gravitational wave physics, and sometimes a very personal interpretation of results. We share with the readers a number of notebooks that will allow them to reproduce some of the most important results in the field, and could even help in carrying out state-of-the-art research. We also include a few original results that we think are helpful in understanding the broader picture.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is a set of lecture notes about black holes and how they affect and produce gravitational waves—the tiny ripples in spacetime that scientists can now detect on Earth. The goal is to help readers understand how black holes work, how matter and light move around them, how spinning black holes can give away energy, why black holes form, and how all of this connects to gravitational wave astronomy. It’s written to prepare students for a future where gravitational wave detections are common and might reveal surprising new physics.

The big questions the paper explores

The authors introduce the core ideas and questions driving modern black hole research. In simple terms, they ask:

- What exactly is a black hole, and do the ones we see match Einstein’s predictions?

- How do matter and light move near black holes?

- What happens at the “edge” of a black hole (the event horizon) and inside it?

- Can spinning black holes give away energy, and if so, how much?

- Does nature always hide “singularities” (places where our equations break down) behind horizons?

- When and how do black holes form?

- How do features around black holes (like gas, stars, or dark matter) change what we observe?

- How can gravitational waves help us test all of the above?

How the paper studies black holes (methods explained simply)

To answer these questions, the authors use Einstein’s theory of gravity, called General Relativity (GR). Here’s what that means in everyday language:

- Spacetime is like a flexible fabric. Massive things like stars and black holes bend this fabric.

- A “metric” is a precise map of how spacetime is bent. Different metrics describe different situations (like non-spinning or spinning black holes).

- Objects and light follow the straightest possible paths in this bent fabric. These paths are called “geodesics.”

- To find out what’s happening near a black hole, the authors solve equations that describe:

- How curved spacetime is near the black hole.

- How matter and light move (their geodesics).

- How stable circular motion is (can something go around the black hole in circles and not fall in?).

- How light gets stretched (redshifted) near the horizon.

- How spinning black holes behave (they use the “Kerr” metric, the standard model for a spinning black hole).

- They sometimes change coordinates (like switching from to new variables) to make tricky regions easier to understand—especially near the horizon.

- They compute simple “cross-sections” that tell us how likely light or particles are to be absorbed by the black hole.

- They use thought experiments (like splitting a particle near a spinning black hole) to show how energy can be extracted.

The notes also include practical computer notebooks (in Mathematica) so readers can reproduce important results themselves.

Main ideas and findings, and why they matter

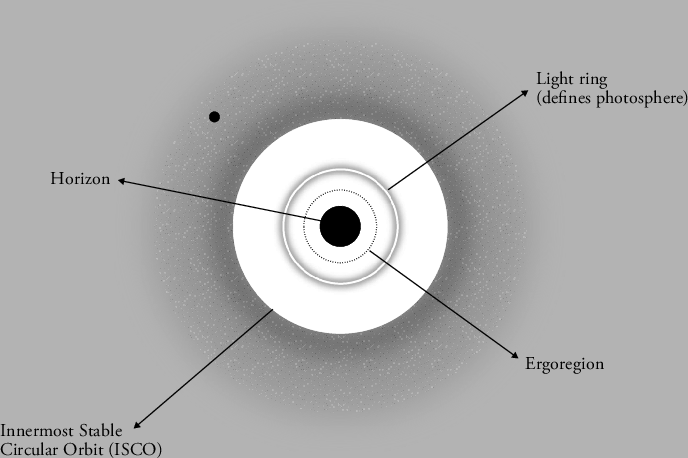

To make the core results easy to remember, think of a black hole as a cosmic whirlpool with several special zones:

- Event horizon (): This is the “no-return” boundary. Once you cross it, you can’t come back out. For a distant observer, nothing ever seems to cross the horizon in finite time—signals get stretched and dimmed (redshifted) very quickly.

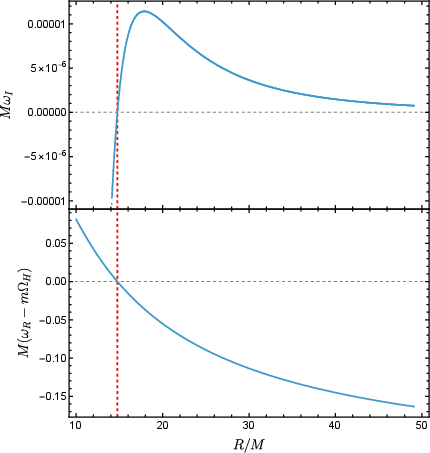

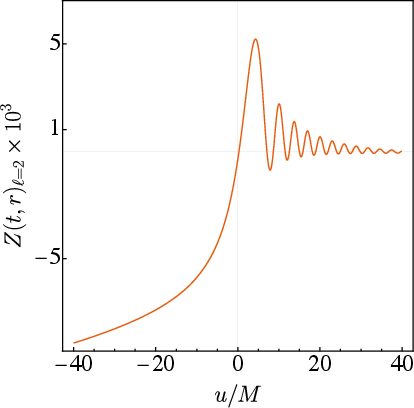

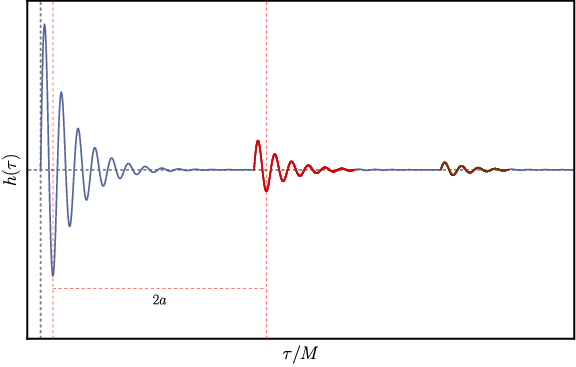

- Photon sphere or light ring (): This is like a racetrack where light can circle the black hole. It’s unstable—small nudges cause light to fly away or fall in—but it temporarily traps light and high-frequency waves. This “ring” sets the tone of the black hole’s “ringdown” sound in gravitational waves after a merger. That matters because:

- The late-time “ringing” LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA hear is controlled by this region.

- It also helps explain features of black hole shadows seen by the Event Horizon Telescope.

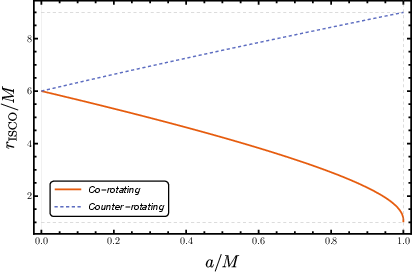

- ISCO (Innermost Stable Circular Orbit, for non-spinning black holes): This is the last radius where matter can orbit stably. Inside this boundary, circular motion isn’t stable anymore—matter spirals in. That affects how disks of gas shine and how they feed black holes.

Important results the notes discuss (in plain English):

- Circular motion of light exists only at one radius () and is unstable. This “light ring” strongly influences the late-time gravitational wave signal (ringdown).

- Stable circular motion for matter exists only outside . This sets the inner edge of bright accretion disks in non-spinning cases.

- Signals from near the horizon are hugely redshifted. For a distant observer, the “fade-out” to extreme redshift happens fast—on a timescale proportional to the black hole’s mass (roughly $4M$ in the units used).

- Black holes absorb light and particles depending on how closely they pass. The notes give simple formulas for the “absorption cross-section” (how likely stuff is to be swallowed), which helps estimate accretion rates.

- Spinning black holes (described by the Kerr metric) have an ergoregion—a zone where spacetime itself is dragged around. In that zone, you can extract energy from the black hole’s spin (Penrose process). The notes:

- Show how energy extraction works and how much energy is available.

- Introduce the “irreducible mass,” , which tells you the part of a black hole’s mass that can’t be extracted. For a maximally spinning black hole, you can, in principle, extract up to about 29% of its mass-energy.

- Nature seems to protect horizons (cosmic censorship). If you try to overspin a black hole (push it beyond the limit so the horizon disappears), the particle or object needed won’t get in. Simulations of violent collisions back this up: in our 4D universe, you still end up with a black hole with a horizon.

- Black holes form when enough energy or mass is squeezed small enough (the hoop conjecture). If you could boost particles to insanely high energies so their “gravity size” becomes larger than their actual size, you’d form black holes.

Why this matters for gravitational waves:

- The merger “ringdown” we detect is shaped by the light ring. By measuring this ringdown, we test whether the black hole matches GR’s predictions (mass, spin, and the Kerr model).

- The ISCO and ergoregion influence how matter flows and radiates, which helps interpret signals from systems with matter (like black hole–neutron star mergers).

- Cosmic censorship and the Kerr bound tell us what end-states are allowed after extreme cosmic events. That keeps predictions reliable.

What this means for the future

These notes give students and researchers a clear framework—both concepts and tools—to interpret gravitational wave signals and black hole observations. As detections become routine:

- We’ll be able to check whether black holes really behave like the simple, elegant solutions of GR (Kerr black holes).

- If we spot strange features (unexpected frequencies, unusually slow damping, odd shadows), they might point to new astrophysical environments (like surrounding matter or dark matter) or even new physics (modifications to gravity).

- The practical notebooks help readers reproduce classic results and explore the frontier themselves, making it easier to do real research.

In short, this paper prepares you to “listen” to black holes—understand the notes they play through gravitational waves—and use that cosmic music to test how gravity works in the most extreme places in the universe.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, concrete list of knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions the paper leaves unresolved. Each item is phrased to guide future researchers toward actionable next steps.

- Quantify the error incurred by assuming vacuum and stationarity for astrophysical black holes embedded in evolving, matter-rich galactic environments; develop perturbative frameworks to include environmental effects and compute their impact on gravitational-wave parameter estimation.

- Extend the scalar-field “no-hair” argument beyond single-minimum potentials to multi-minima, non-minimal couplings, and time-dependent fields; systematically map the existence, stability, and astrophysical formation channels of hairy black holes (scalar/vector/tensor) and derive discriminating GW and EM signatures.

- Establish a robust, quantitative correspondence between light-ring properties and the full quasinormal-mode spectrum beyond the eikonal limit, including the effects of spin, accretion flows, and exterior matter; determine how departures from vacuum Kerr alter ringdown mode frequencies and damping times.

- Determine how realistic environments (plasma, magnetic fields, radiation pressure, dark-matter spikes) shift the ISCO and modify circular-orbit stability; link these shifts to observable EM spectra and inspiral phasing in GWs.

- Model the time-dependent redshift and photon-ring relaxation for infalling emitters using realistic emission geometries and plasma dispersion; predict transient observables and timing (e.g., EHT, mm/sub-mm VLBI, X-ray reverberation) including non-radial emission and lensing delays.

- Generalize absorption/scattering cross-sections from Schwarzschild to Kerr for photons and gravitons, including finite-frequency, polarization, and wave interference effects; provide validated numerical/analytic fits usable in GW/EM modeling pipelines.

- Quantify the efficiency and astrophysical viability of ergoregion energy-extraction mechanisms (Penrose vs. Blandford–Znajek) under realistic dissipation, backreaction, and horizon area increase; connect to measurable BH spin-down rates and jet energetics.

- Strengthen weak cosmic censorship tests in GR by exploring broader initial data and matter content (electric charge, Λ≠0, anisotropic fluids, boson clouds), and boundary conditions (AdS, cosmological); derive quantitative thresholds for potential violations and propose observational discriminants.

- Formalize the hoop conjecture for non-spherical, highly relativistic, and quantum regimes; derive necessary and sufficient conditions for horizon formation and test them via numerical relativity with diverse stress-energy tensors.

- Develop horizon diagnostics in GW data: quantify tidal heating, horizon absorption, and potential near-horizon reflectivity (echoes); assess systematics to robustly distinguish horizons from exotic compact objects.

- Assess environmental biases on ringdown-based Kerr tests (e.g., residual disks, boson clouds, accretion flows); create inference strategies that remain valid in non-vacuum spacetimes and quantify the residual uncertainty budget.

- Constrain the possibility and magnitude of astrophysical black-hole electric charge: model neutralization timescales and derive GW/EM signatures (e.g., ringdown shifts, plasma dynamics) to set empirical bounds.

- Tighten bounds on a possible graviton mass using dispersion in ringdown and propagation across bands; integrate multi-band GW observations and account for environmental dispersive media.

- Investigate maximum luminosity bounds (e.g., near the c5/G scale) in strong-field dynamical events; validate with numerical relativity and explore modifications in alternative gravity theories.

- Advance the rigorous understanding of Kerr stability: pursue proof of nonlinear stability in vacuum; analyze potential instabilities triggered by coupling to matter shells or ergoregions and quantify astrophysical relevance.

- Quantify superradiant growth rates for boson clouds around Kerr BHs across particle masses/spins; compute continuous-wave GW templates, assess detectability, and evaluate spin distributions as indirect constraints.

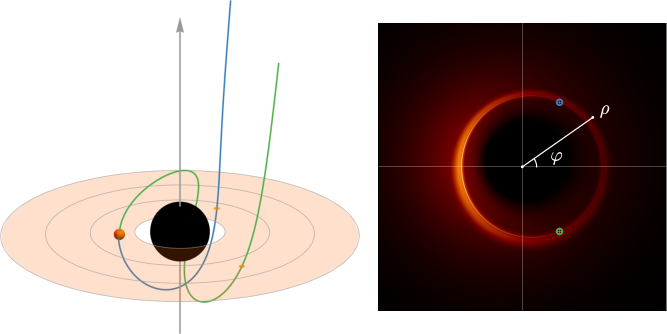

- Deliver precise, emission-model-aware predictions for photon-ring observables in Kerr (and deformations), including brightness enhancements, time delays, and frame dragging; develop inversion methods to constrain spacetime parameters from EHT-like data while handling degeneracies with emission physics.

- Provide high-order analytic approximations for near-critical scattering (deflection angles, time delays, lensing “glories”) in Kerr; benchmark against ray-tracing and wave optics to support data interpretation in EM and GW contexts.

- Explore horizon-destruction scenarios in modified gravity: map parameter regimes where Kerr-like bounds can be violated, characterize end-states (naked singularities vs. new horizons), and propose observational tests distinguishing GR from alternatives.

- Integrate BH formation pathways and growth (collapse, hierarchical mergers, accretion) into population models consistent with energy extraction and environmental interactions; use GW catalogs to constrain mass/spin distributions and their evolution.

- Provide full derivational detail and reproducibility checks for notebooks referenced in the text, including boundary conditions and numerical validation, to enable robust replication and extension of the presented results.

Glossary

- Asymptotically flat: A spacetime that approaches flat (Minkowski) geometry at large distances, with vanishing gravitational field far away. "It is a classical result, worked out in the notebook \coderef{code:Field-Equations.nb}, that the unique {\bf vacuum}, spherically symmetric, and asymptotically flat solution is the Schwarzschild solution,"

- Axisymmetric: Having rotational symmetry around a single axis; in GR, a spacetime invariant under rotations about an axis. "It turns out that the Kerr spacetime is the only asymptotically flat, axisymmetric, stationary, and vacuum solution of the field equations"

- Boyer–Lindquist coordinates: A coordinate system used to express the Kerr metric, analogous to spherical coordinates for rotating spacetimes. "Write down the Kerr metric in Boyer–Lindquist coordinates and show that it satisfies the vacuum Einstein Field Equations."

- Christodoulou’s irreducible mass: The portion of a black hole’s mass that cannot be extracted, related to the horizon area; sets the limit of rotational energy extraction. "This is Christodoulou's irreducible mass~\cite{Christodoulou:1970wf}."

- Cosmic Censorship (weak Cosmic Censorship): The conjecture that singularities produced by gravitational collapse are hidden behind horizons and cannot be observed from infinity. "This is the subject of the weak Cosmic Censorship, that basically asserts that such a possibility does not happen"

- Cross-section: An effective area quantifying the likelihood of absorption or interaction, e.g., of particles by a black hole. "The cross-section for absorption is then"

- Effective potential: A function governing radial motion (geodesics) that encodes gravitational effects as if in a potential energy landscape. "Using the effective potential \eqref{eq_Eff_potential_geodesics}, the conditions for circular motion are ... and ..."

- Ergoregion: The region outside a rotating black hole where no timelike observer can remain at rest; enables negative-energy states and energy extraction. "Such regions are called ergoregions, and for the Kerr geometry it is easy to see that it comprises the exterior of the horizon with along the equator for example."

- Event horizon: The boundary beyond which events cannot influence distant observers; the “point of no return” of a black hole. "The surface is the event horizon of the black hole."

- Frame-dragging: The dragging of inertial frames by a rotating mass, causing precession and twisting of spacetime. "Frame-dragging is apparent also here."

- Geodesic: The path of free-falling particles or light in curved spacetime, determined by the metric; extremizes proper time or null interval. "The Euler-Lagrange equations are equivalent to the geodesic equations,"

- Geometrized units: A system where fundamental constants are set to unity (typically ), making mass, length, and time share dimensions. "but moving forward, we will use geometrized units with ."

- Hoop Conjecture: A heuristic criterion for black hole formation stating that collapse occurs when mass can be enclosed by a hoop of circumference proportional to the Schwarzschild radius. "This is the Hoop Conjecture~\cite{1972mwm..book..231T,Choptuik:2009ww} and states that “An imploding object forms a black hole when a circular hoop with circumference times the Schwarzschild radius of the object can be made that encloses the object in all directions.”"

- Impact parameter: A measure of the lateral offset of a trajectory at infinity; for null geodesics, . "Let us now consider null particles with some finite impact parameter at infinity , where we define "

- Innermost Stable Circular Orbit (ISCO): The smallest radius at which stable circular timelike orbits exist around a black hole. "The circular orbit at radius is, therefore, usually referred to as the Innermost Stable Circular Orbit (ISCO)."

- Kerr bound: The maximal spin-to-mass ratio required for a rotating black hole to possess a horizon. "We can use a similar framework to think about violating the Kerr bound~\eqref{Kerr_bound}."

- Kerr spacetime: The rotating black hole solution characterized by mass and angular momentum . "It turns out that the Kerr spacetime is the only asymptotically flat, axisymmetric, stationary, and vacuum solution of the field equations"

- Kretschmann scalar: The curvature invariant used to diagnose singularities. "Then the next higher-order scalar built out of the geometry is the Kretschmann scalar (see notebook \coderef{code:Field-Equations.nb}),"

- Light ring: The unstable circular null orbit; the equatorial projection of the photon sphere in spherically symmetric spacetimes. "The projection onto the equatorial plane is also frequently referred to as the light ring."

- Metric theory: A theory where gravity is encoded in a spacetime metric that determines distances, times, and geodesics. "we will always assume that gravity is still described by a metric theory."

- No-hair property: The statement that certain black holes are fully characterized by a small set of parameters (e.g., mass and spin) without additional “hair” like scalar profiles. "We call this a no-hair property."

- Penrose process: An energy extraction mechanism exploiting the ergoregion by splitting a particle into fragments, one with negative energy falling into the black hole. "Due to its historical relevance, let's take a closer look at a particular energy extraction mechanism, the so-called Penrose process~\cite{Penrose:1964wq,Brito:2015oca}."

- Photon sphere: A spherical region where light can orbit on circular null geodesics; at for Schwarzschild. "It exists at a single location, defining the photon sphere (in the case of spherical symmetry)."

- Quasinormal modes (ringdown modes): The characteristic damped oscillations describing how black holes relax after perturbations. "We think of the light ring, or the photon sphere, as the location where the characteristic modes (called quasinormal modes or ringdown modes) of black holes are localized."

- Ricci scalar: A scalar curvature obtained by contracting the Ricci tensor; measures curvature density. "Since this is a vacuum spacetime, the Ricci tensor—and therefore the Ricci scalar—vanishes by construction."

- Ricci tensor: A contraction of the Riemann tensor encoding curvature that influences volume changes and geodesic convergence. "Since this is a vacuum spacetime, the Ricci tensor—and therefore the Ricci scalar—vanishes by construction."

- Schwarzschild solution: The unique spherically symmetric vacuum solution describing a non-rotating black hole. "It is a classical result, worked out in the notebook \coderef{code:Field-Equations.nb}, that the unique {\bf vacuum}, spherically symmetric, and asymptotically flat solution is the Schwarzschild solution,"

- Stationary spacetime: A spacetime whose geometry does not change with time; possesses a timelike Killing vector. "It turns out that the Kerr spacetime is the only asymptotically flat, axisymmetric, stationary, and vacuum solution of the field equations"

- Stress tensor: The stress-energy tensor , representing energy, momentum, and stress content of matter/fields. "and follow from the vanishing of the divergence of stress-tensor (see Sec. 19.1 of Ref."

- Superradiance: The amplification of waves scattering off a rotating black hole, extracting rotational energy. "supported through superradiance (more on this effect in Section~\ref{sec:superradiance})."

- Trapped surface: A closed 2-surface where both ingoing and outgoing light rays converge, signaling gravitational collapse. "Indeed, gravitational collapse of “reasonable” matter to form a trapped surface results in a “singularity”, where at least one of the following holds"

- Very large baseline interferometry: An astronomical technique using widely separated radio telescopes to achieve high angular resolution. "The advent of very large baseline interferometry, and of gravitational wave astronomy that can monitor the coalescence of compact binaries across millions of light-years, provides access to the most mysterious macroscopic objects: black holes."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The paper’s lecture notes, derivations, and shared computational notebooks enable several practical workflows and decision-making aids that can be deployed now across research, observatories, and education.

- Gravitational-wave data analysis and black hole spectroscopy (academia, software/HPC)

- Use quasinormal mode localization at the light ring and the damping scale 1/λ = 3√3 M to build ringdown-only templates for parameter estimation (mass, spin), consistency tests of General Relativity, and event cataloging.

- Tools/products/workflows: matched-filter libraries enriched with damped-sinusoid models; Bayesian parameter estimation modules; quality-control metrics for late-time signal segments; integration into LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA pipelines and open-source packages (e.g., Bilby, PyCBC).

- Assumptions/dependencies: sufficient SNR in the ringdown; validity of GR in strong-field regime; accurate detector calibration; minimal environmental contamination from matter near the horizon.

- Shadow and photon-ring modeling for VLBI/EHT imaging (academia, observatories, software)

- Apply photon sphere properties and critical impact parameter bcrit = 3√3 M to constrain shadow geometry, infer spin orientation, and interpret multi-orbit lensed features (“photon rings”) in black hole images.

- Tools/products/workflows: ray-tracing codes; forward-modeling pipelines that map emitting regions to observer screens; synthetic image generation and parameter fitting; visualization assets for public communication.

- Assumptions/dependencies: optically thin emission models in the relevant bands; adequate resolution and baseline coverage; stationary approximations over observation windows.

- Accretion flow and disk–corona modeling via ISCO and absorption cross-sections (academia, astrophysics, software)

- Use ISCO at r = 6M (non-spinning case) and timelike/light absorption cross-sections σabs,light = 27πM² and σabs,low-E = 16πM²/v² to estimate disk truncation, inflow rates, and radiative efficiency in compact-object environments.

- Tools/products/workflows: coupling GR geodesic libraries with GRMHD solvers (e.g., Athena++, HARM); parameter sweeps for accretion models; uncertainty quantification in spectral fitting.

- Assumptions/dependencies: near-vacuum exterior as a working approximation; negligible magnetic and radiation-pressure effects near the light ring for the use case; accurate distance and mass estimates.

- Multi-messenger follow-up timing heuristics (academia, observatories, policy)

- Leverage exponential redshift behavior near the horizon with characteristic observer timescale ≈ 4M to prioritize fast follow-up of potential EM counterparts (when present) after GW triggers.

- Tools/products/workflows: automated scheduling heuristics in telescope networks; alert system rules that incorporate compact-object mass estimates to time-slice observation windows.

- Assumptions/dependencies: presence of EM emission channels; reliable mass/spin inference from prompt GW analysis; coordination across facilities.

- Curriculum development and reproducible training assets (education, academia, software)

- Integrate the provided Mathematica notebooks and solved exercises into graduate-level courses and workshops to teach strong-field GR, geodesics, ringdown physics, and the Kerr geometry.

- Tools/products/workflows: translation of notebooks to Jupyter/Python; continuous assessment modules; version-controlled repositories for teaching and research reproducibility.

- Assumptions/dependencies: licensing/access to Mathematica or equivalent tools; instructor familiarity with GR; alignment with departmental syllabi.

- Safety and public communication for high-energy experiments (policy, public outreach)

- Use the hoop conjecture and cosmic censorship results to inform risk assessments and outreach materials explaining why terrestrial accelerators do not pose black-hole risks (formation requires unattainable γ factors; strong theoretical control).

- Tools/products/workflows: briefing documents for funding bodies; FAQs and visualizations for public audiences; alignment with institutional safety committees.

- Assumptions/dependencies: acceptance of GR-based reasoning; consistent messaging across collaborating institutions.

Long-Term Applications

Beyond immediate deployment, the paper motivates strategic directions and potential products that require new instruments, scaling efforts, or research advances.

- Dark matter searches via superradiance and BH environment tests (academia, observatories, software)

- Exploit superradiant instabilities around spinning black holes to search for ultralight bosons through characteristic GW signatures and spin distributions.

- Tools/products/workflows: joint GW–EM inference frameworks; population analyses of BH spins; template banks for superradiant-induced spectral features; integration with LISA/Einstein Telescope pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: next-generation detector sensitivity; robust modeling of environmental effects; theoretical priors on boson mass ranges.

- Next-generation black hole spectroscopy and GR stress tests (academia, observatories, policy)

- Systematically test uniqueness theorems and ringdown predictions with larger catalogs from future detectors to constrain deviations from Kerr or metric theories.

- Tools/products/workflows: standardized ringdown catalogs; cross-mission analysis protocols; funding for long-baseline and space-based detectors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: sustained international investment (LISA, ET, CE); improved calibration; development of model-agnostic analysis methods.

- Analog gravity and rotational energy extraction devices (energy, photonics, academia)

- Translate Penrose process and superradiance concepts to laboratory analogs (fluids, photonic metamaterials) to create wave-amplification devices or rotational energy-harvesting demonstrators.

- Tools/products/workflows: metamaterial design pipelines; experimental platforms for analog ergoregions; IP portfolios around wave amplifiers and sensors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: feasible analog implementations with controllable dissipation; regulatory and safety compliance; interdisciplinary teams (physics, materials, EE).

- Digital twins of galactic centers and time-dependent BH environments (academia, software/HPC)

- Build multi-physics simulations coupling GR, MHD, radiation transport, and geodesics to study nonstationary, matter-rich environments around SMBHs and their observational signatures.

- Tools/products/workflows: HPC-accelerated solvers; cloud-native workflows; uncertainty-aware forward models for EM/GW data fusion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: exascale computing resources; validated microphysics; sustained data access from observatories.

- Collider and cosmic-ray phenomenology under the hoop conjecture (policy, academia)

- Refine limits on black-hole production thresholds in extreme collisions and update safety dossiers and theoretical guidance for future accelerators and cosmic-ray facilities.

- Tools/products/workflows: phenomenological models; risk assessment templates; engagement with oversight bodies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus on micro-black-hole evaporation physics; empirical constraints from cosmic-ray observations.

- Navigation, timing, and sensing spin-induced effects in space (space systems, academia)

- Extend frame-dragging/ergoregion insights to precision orbit determination and novel sensing modalities near compact objects, relevant to future deep-space missions.

- Tools/products/workflows: mission design tools that incorporate relativistic corrections; simulation environments for close-approach trajectories; specialized instrumentation concepts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: mission opportunities near compact objects; measurement technology advances; robust relativistic navigation frameworks.

- Standardized open-science ecosystems for strong-field gravity (academia, software, policy)

- Scale the paper’s reproducibility ethos (shared notebooks and exercises) into community standards for code sharing, benchmarking, and education across GR and GW science.

- Tools/products/workflows: interoperable libraries (Python/C++); test suites; FAIR data repositories; governance policies for collaborative development.

- Assumptions/dependencies: community adoption; sustainable funding for maintenance; training and documentation efforts.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.