From Power to Precision: Learning Fine-grained Dexterity for Multi-fingered Robotic Hands (2511.13710v1)

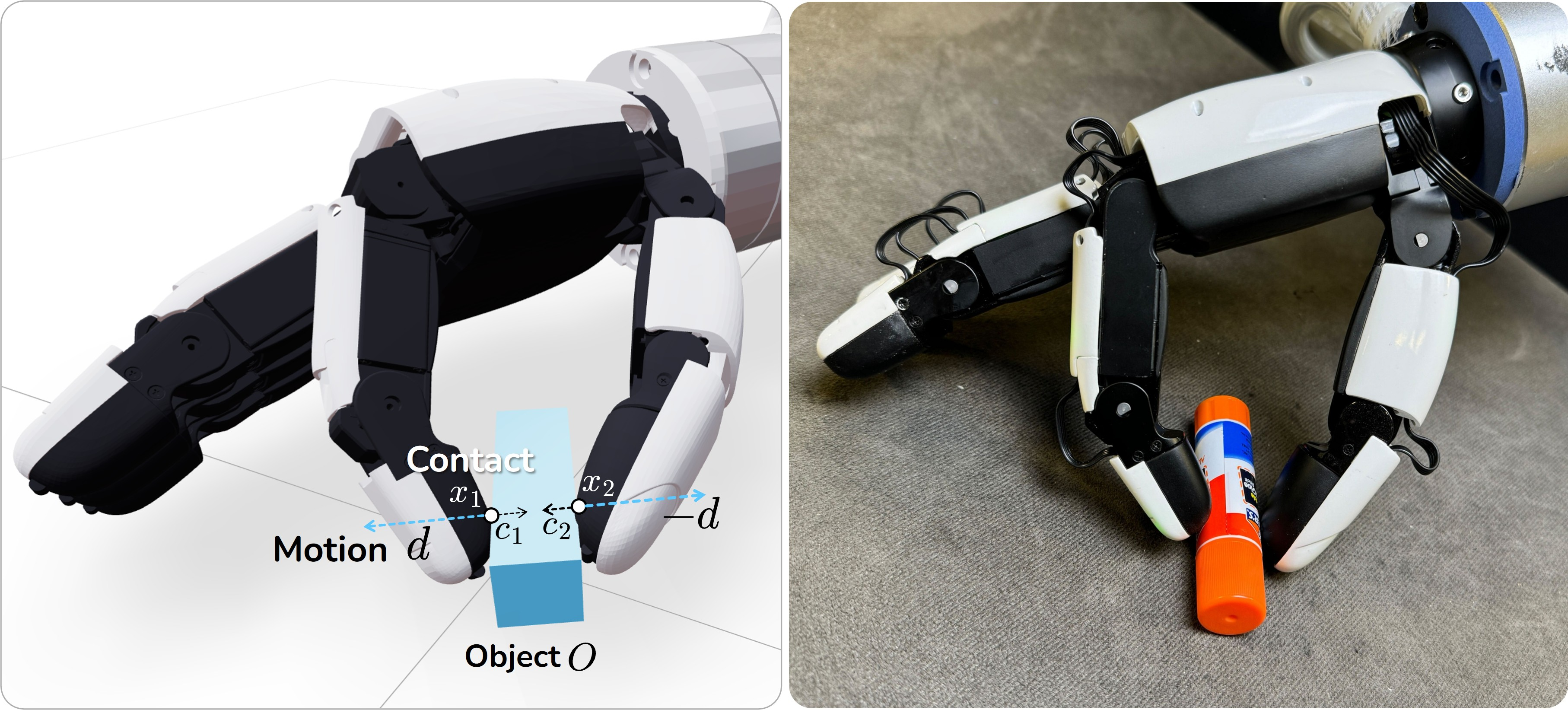

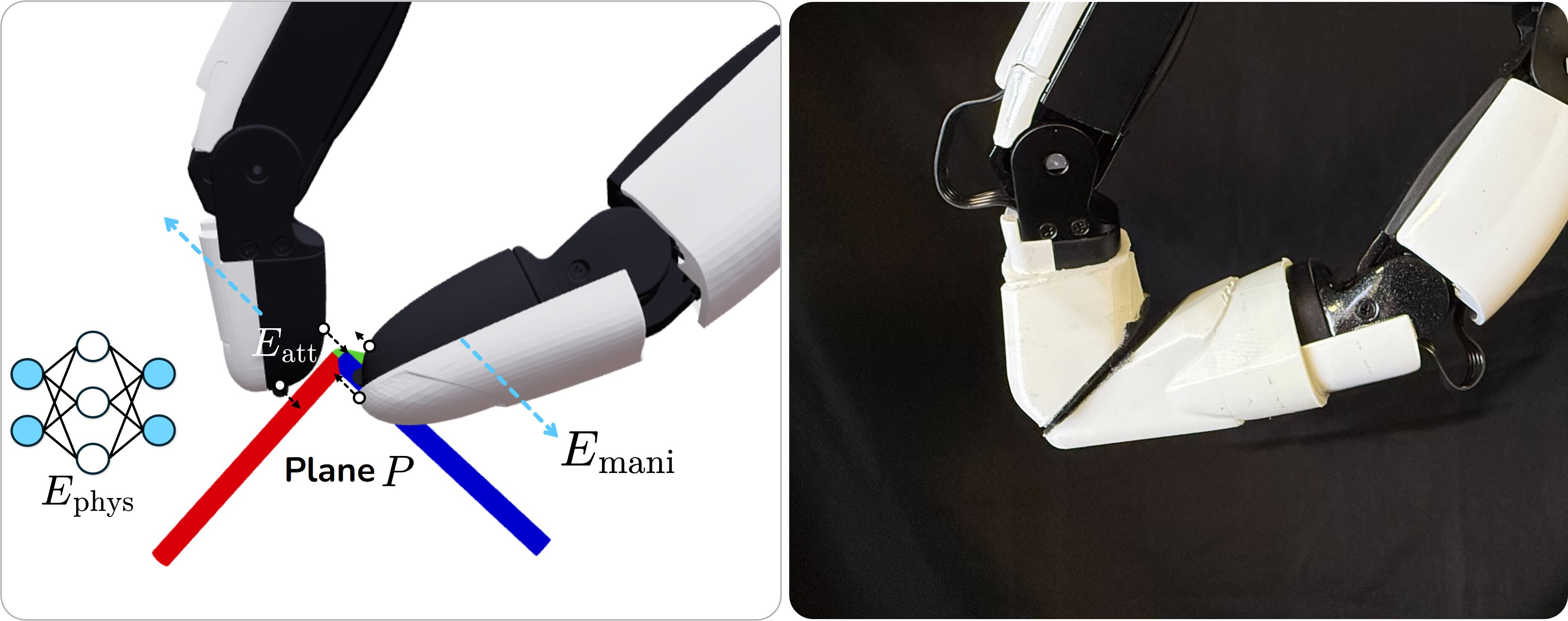

Abstract: Human grasps can be roughly categorized into two types: power grasps and precision grasps. Precision grasping enables tool use and is believed to have influenced human evolution. Today's multi-fingered robotic hands are effective in power grasps, but for tasks requiring precision, parallel grippers are still more widely adopted. This contrast highlights a key limitation in current robotic hand design: the difficulty of achieving both stable power grasps and precise, fine-grained manipulation within a single, versatile system. In this work, we bridge this gap by jointly optimizing the control and hardware design of a multi-fingered dexterous hand, enabling both power and precision manipulation. Rather than redesigning the entire hand, we introduce a lightweight fingertip geometry modification, represent it as a contact plane, and jointly optimize its parameters along with the corresponding control. Our control strategy dynamically switches between power and precision manipulation and simplifies precision control into parallel thumb-index motions, which proves robust for sim-to-real transfer. On the design side, we leverage large-scale simulation to optimize the fingertip geometry using a differentiable neural-physics surrogate model. We validate our approach through extensive experiments in both sim-to-real and real-to-real settings. Our method achieves an 82.5% zero-shot success rate on unseen objects in sim-to-real precision grasping, and a 93.3% success rate in challenging real-world tasks involving bread pinching. These results demonstrate that our co-design framework can significantly enhance the fine-grained manipulation ability of multi-fingered hands without reducing their ability for power grasps. Our project page is at https://jianglongye.com/power-to-precision

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper is about teaching robot hands to be both strong and precise—like humans. Human hands use two main types of grips:

- Power grips: wrapping your whole hand around something big (like holding a frying pan).

- Precision grips: using your fingertips to carefully pinch and move small things (like picking up a nut or inserting a battery).

Robot hands are already good at power grips, but they struggle with delicate, precise movements. The researchers created a method that combines smart control software with a small hardware upgrade to help multi-fingered robot hands do both types of tasks well.

Objectives: What questions were the researchers trying to answer?

The team focused on three simple goals:

- How can we make existing robot hands better at precise fingertip work without rebuilding them from scratch?

- Can one hand and one control system handle both power and precision tasks?

- Will the method work both in simulation (virtual testing) and in the real world?

Methods: How did they do it?

The approach has two parts that work together: smarter control and a small hardware tweak.

Smarter control: choosing and simplifying movements

- Think of a robot hand like a toolbox with many tools (its fingers). For small objects, using all tools at once is confusing and fragile.

- The researchers made the hand “switch modes” based on the object:

- Power mode for big, heavy items.

- Precision mode for small, thin, or delicate items.

- In precision mode, they simplified the hand’s movement to act like a pair of tweezers:

- Only the thumb and index finger move.

- They move straight toward each other in parallel, like chopsticks closing on a noodle.

- A “neural switcher” (a small AI classifier) looks at the object and decides which mode to use.

Small hardware upgrade: better fingertip covers

- Instead of redesigning the whole hand, they added simple, 3D-printed fingertip covers.

- These covers are shaped by imagining a flat contact “plane” on each fingertip—like a small, flat pad that gives more surface to pinch tiny items.

- They tested many designs in large-scale simulation and trained a “neural physics” model (a learned predictor) to pick designs that would work best in real life. Think of it like trying many prototypes in a video game and teaching an AI to guess which shape will be best before you print it.

Training and validation: learning from examples

- Imitation learning: The robot learns by watching example actions (demonstrations) collected in two ways:

- Simulation demos for grasping many different objects.

- Teleoperation demos (a person controls the robot remotely) for tricky real-world tasks.

- They trained two policies (control programs):

- One for power grasps.

- One for precision grasps.

- The neural switcher decides which policy to apply at run time.

Simple explanations of technical terms

- Simulation to real (“sim-to-real”): Training in a virtual world, then using it on a real robot.

- Surrogate model: A quick AI “shortcut” that predicts how well a design will work, instead of running slow physics every time.

- Parallel finger motion: Fingers move straight toward each other, like closing a pair of tongs.

- Teleoperation: A human moves the robot using a controller; the robot records these moves as examples to learn from.

Results: What did they find and why is it important?

Main findings:

- Precision grasps in the real world improved dramatically:

- Against a strong baseline, their method achieved 82.5% success on unseen objects in zero-shot sim-to-real tests (meaning no fine-tuning on those objects), compared to 12.5% for the baseline.

- Power grips remained strong:

- Their upgrades didn’t hurt the robot’s ability to hold big objects securely.

- Real-world task performance was much better on delicate jobs:

- Bread pinch: 93.3% success (hard because pressing too hard crushes the bread).

- Nut onto peg (tiny M4 nut onto an M3 bolt): 66.7% success.

- Cooking setup: picking asparagus (precision) and lifting a pan (power) in sequence reached 73.3% success.

- Multi-pen grasp and battery insert tasks also showed strong gains.

Why this matters:

- By simplifying precision moves (thumb + index closing in parallel) and improving fingertip shapes, the robot became more reliable at tiny, delicate tasks. This is important for real-world jobs like assembly, packaging, kitchen work, or lab automation.

Implications: What could this change?

- Practical upgrades: You don’t need to buy new robot hands—simple fingertip covers and smarter control can make existing hands much better at delicate work.

- Fewer sensors needed: The method works without expensive tactile sensors, relying on good control and smart design.

- Better sim-to-real transfer: Simple, robust motions (like parallel pinching) make it easier for robots to perform in the messy real world, not just in clean simulations.

- Broader use: This approach could help robots handle a wider range of tasks—from heavy lifting to precise assembly—making them more useful in factories, kitchens, hospitals, and homes.

In short: The paper shows a practical way to make robot hands both strong and careful by combining a tiny hardware upgrade with simple, smart control.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a consolidated list of the paper’s unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that future work could address:

- Precision control is limited to thumb–index pinches with parallel motions; the framework does not explore other precision grasp types (tripod, lateral pinch, tri-digital, ring–thumb) or in-hand reorientation/rolling that require coordinated multi-finger dynamics.

- The neural switcher classifies only “power vs precision” based on object geometry; task context, multi-step sequences, and dynamic within-task switching (e.g., changing grasp modes mid-trajectory) are not evaluated, especially in real-world autonomous executions.

- Position-based Jacobian pseudoinverse control lacks explicit force/torque regulation and tactile feedback; contact forces are not measured or limited, which is risky for delicate objects (e.g., bread pinch) and makes closed-loop contact control an open need.

- Fingertip geometry is constrained to a single flat contact plane; alternative shapes (V-groove, concave/convex surfaces, compliant skins, textured or anisotropic friction surfaces) and task-conditioned geometries are not compared or optimized.

- Material properties of the fingertip covers (e.g., friction coefficient, stiffness/compliance, surface finish, thickness) and their impact on grasp stability, small-object precision, and power-grasp capacity are not characterized.

- Long-term durability, wear, and maintenance of 3D-printed covers are untested; effects of repeated cycles, deformation, surface polishing, and attachment stability over time remain unknown.

- Trade-offs introduced by the geometry modification on power grasps are only assessed via success rates; quantitative analysis of payload capacity, maximal disturbance rejection, and force-closure margins is missing.

- The neural physics surrogate is trained solely on simulated outcomes; model accuracy, calibration to real-world dynamics, and any sim-to-real adaptation strategies are not reported.

- External perturbation forces are kept during evaluation but are not calibrated to real-world magnitudes or contact conditions; it’s unclear how these disturbances map to realistic deployment scenarios.

- Object categorization into “precision vs power” is derived from optimization success rather than human-defined semantics or task requirements, potentially biasing dataset composition and learned policies.

- Generalization across hardware is validated on only two platforms (XHand, Inspire/G1); transfer to other multi-fingered hands (e.g., Allegro, Shadow, Robotiq) with different kinematics and fingertip morphologies remains unproven.

- Perception relies on point clouds; robustness under occlusions, small-object visibility, transparent/reflective materials, and cluttered scenes is not evaluated, nor are multi-view or active perception strategies.

- Real-to-real training uses small demonstration sets (15 per task) with limited diversity; sample efficiency, generalization to more objects/tasks, and cross-operator variability are not analyzed.

- No direct baseline against high-quality two-finger parallel grippers on the same precision tasks; it remains unclear whether the proposed system meets or exceeds the performance of specialized parallel grippers.

- The pre-grasp parallel motion uses a fixed step size α and open-loop planning; adaptive step sizing, closed-loop visual/tactile servoing, and on-the-fly error correction are not incorporated or tested.

- During precision grasps, non-thumb–index fingers are fixed; whether additional fingers could be used as passive stabilizers or active aids without degrading precision is unexplored.

- The precise grasp optimization success rate in simulation is low (5.35%); bottlenecks such as objective weighting, contact sampling (n), Jacobian conditioning, and non-convexity of the search space need diagnosis and improved formulations.

- The surrogate’s predictive performance (metrics, calibration, uncertainty) is not reported; without accuracy/uncertainty quantification, the contribution of E_phys is hard to interpret or trust for design choices.

- Autonomous policy and grasp-mode switching are handled in separate pipelines (DexSimple + switcher for sim-to-real; ACT for real-to-real); a unified, end-to-end autonomous framework with integrated switching is not demonstrated.

- Real-time performance (latency, compute footprint) of the switcher and policies is not reported; feasibility on embedded hardware and responsiveness during fast manipulation remain open.

- Safety constraints (max contact force/torque, collision avoidance with environment, emergency stop thresholds) are not explicitly encoded in the controllers or learning objectives.

- Task diversity is limited; precision tasks involving tight-tolerance insertions (beyond “nut onto peg”), screw driving, key insertion, or deformable/porous/soft objects are not comprehensively evaluated.

- Failure modes are not systematically analyzed; categorization of slips, misalignments, occlusions, joint-limit violations, and corrective strategies (e.g., regrasp, recovery behaviors) are missing.

- Manufacturing reproducibility is insufficiently detailed; sensitivity to print tolerances, post-processing (sanding, coating), surface roughness, and installation/calibration procedures should be quantified for replication.

- The effect of optimized fingertip geometry on sensor integration (e.g., compatibility with embedded tactile sensors or vision-in-the-hand) is not considered; co-design with sensing remains an open direction.

- Policy inputs exclude explicit hand state abstractions (e.g., gripper aperture estimation); whether richer proprioceptive/force/tactile representations would improve learning and robustness is untested.

- Bread pinch and battery insert successes are presented on limited instances; systematic benchmarking across varied breads (thickness, moisture), battery types/sockets (fit tolerances), and quantitative metrics (pose error, insertion force) are not provided.

- Complex regrasping and tool-use sequences (e.g., in-hand reorientation before insertion, handovers) are not studied; extending beyond single pinch/power events is a key open challenge.

- Accessibility and reproducibility are unclear; public release of CAD for covers, optimization code, objective weights, trained switcher/surrogates, and datasets would enable independent validation and broader adoption.

Glossary

- ACT (Action Chunking Transformer): A transformer-based policy architecture that outputs sequences of actions for robot control. "Finally, an ACT policy~\cite{zhao2023learning} is trained on these teleoperated demonstrations for deployment."

- Co-design: Joint optimization of hardware (morphology) and control within a unified framework. "This versatility and dexterity are achieved through a co-design framework for both control and fingertip-geometry optimization."

- Contact plane: A planar representation of fingertip contact geometry used to simplify and optimize precision manipulation. "represent it as a contact plane, and jointly optimize its parameters along with the corresponding control."

- Convex hull: The smallest convex shape enclosing a set of points; used here to derive printable fingertip covers. "Given , we project a slightly inflated convex hull of the fingertip onto it and 3D print the resulting union geometry."

- Directional manipulability: A measure of how easily an end-effector can move in a specified direction given kinematic constraints. "We measure this using directional manipulability~\cite{yoshikawa1985manipulability}:"

- Force closure: A grasp condition where contact forces can counteract any external wrench, yielding a stable hold. "a common way to collect demonstrations for dexterous grasping is to first optimize for force closure and then apply motion planning combined with simulation filtering"

- Grasp map: A matrix mapping fingertip contact forces to the resultant wrench on the object. "The grasp map is"

- Grasp synthesis: Computational generation of grasp configurations that satisfy task-specific objectives or constraints. "thumb-index motion generation for both grasp synthesis and real-world teleoperation."

- Jacobian pseudoinverse: The Moore–Penrose inverse of the Jacobian used to compute joint updates that achieve desired Cartesian motions. "The required joint velocity are calculated using the Jacobian pseudoinverse "

- ManiSkill: A physics-based robot manipulation simulator used for data filtering and policy training. "All demonstrations are filtered using the ManiSkill simulator~\cite{taomaniskill3}."

- MLP (Multi-Layer Perceptron): A feedforward neural network composed of multiple fully connected layers. "We then add a switcher consisting of PointNet~\cite{qi2017pointnet} and an MLP to predict whether an object should be grasped with a power grasp or a precision grasp"

- Neural physics surrogate model: A learned differentiable model that approximates simulation outcomes to provide gradients for design/control optimization. "we leverage large-scale simulation to optimize the fingertip geometry using a differentiable neural-physics surrogate model."

- Objaverse: A large-scale dataset of 3D object models used for training and evaluation. "Our dataset includes 7k Objaverse~\cite{deitke2023objaverse} objects and 1k primitive shapes (spheres, boxes, cylinders) of various sizes."

- Parallel grippers: Two-finger grippers that move in parallel, commonly used for precise manipulation tasks. "two-finger parallel grippers are more widely adopted"

- Point cloud: A set of 3D points representing object geometry used for perception and policy inputs. "leverage large-scale simulation to learn dexterous grasping policies and employ point cloud observations for robust sim-to-real transfer."

- PointNet: A neural network architecture for processing point clouds directly without voxelization. "We then add a switcher consisting of PointNet~\cite{qi2017pointnet} and an MLP"

- Precision grasp: A grasp type where the thumb opposes fingertips to enable fine, accurate object manipulation. "the precision grasp is particularly associated with the fine-grained manipulation required for tool use in early humans"

- Proprioception: Internal sensing of the robot’s joint positions used as input to control policies. "with XArm-XHand joint position as proprioception information."

- Retargeting: Mapping human motion (e.g., teleoperator hand) to a robot’s kinematics for demonstration collection. "The standard position-based retargeting~\cite{qin2023anyteleop} struggles with fine-grained actions such as pinching a nut."

- Signed distance function (SDF): A scalar field that returns the signed distance from any point to a surface, used for generating pre-grasp motions. "is based on the object's signed distance function (SDF), which pushes fingers toward the object surface"

- Sim-to-real gap: Differences in sensing, calibration, and dynamics between simulation and the real world that impede direct deployment. "Deploying these grasps to the real world is impractical due to the sim-to-real gap."

- Sim-to-real transfer: Deploying policies learned in simulation directly in the real world. "which proves robust for sim-to-real transfer."

- Skew-symmetric matrix: A matrix representation used to encode cross products in grasp modeling. " is the skew-symmetric matrix of ."

- Teleoperation: Human-in-the-loop control of a robot from a distance to collect demonstrations or perform tasks. "Teleoperation is used to collect demonstrations."

- Wrench: A 6D vector of force and torque describing the effect of contact forces on an object. "which encourages the net wrench to approach zero for the thumb-index grasp."

- Zero-shot: Evaluation or deployment without task-specific fine-tuning on the target environment. "Our method achieves an 82.5\% zero-shot success rate on unseen objects in sim-to-real precision grasping"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following items translate the paper’s findings into deployable use cases across sectors. Each item notes potential tools/workflows and key assumptions or dependencies that affect feasibility.

- Retrofit fingertip covers to upgrade existing robot hands for precision work — sectors: manufacturing, warehousing, service robotics

- What: 3D-printable, plane-based fingertip covers that increase contact area and stability for thumb–index pinches, installed on commercial multi-fingered hands (e.g., XHand, Inspire).

- Tools/products/workflows: “Fingertip Cover Generator” that outputs STL from a hand model; installer jig; materials selection guide (friction, durability).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate CAD/mesh for the hand; suitable 3D-print materials (food-safe as needed); simple attachment mechanism; hand kinematic calibration.

- Precision bin-picking and kitting of small parts — sectors: electronics manufacturing, automotive, general assembly, warehousing/e-commerce

- What: Robust pinch grasps of pens, nuts, batteries, small fixtures; mode switching between power and precision for mixed kits.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Grasp Mode Switcher” (PointNet+MLP) with a two-policy stack (power/precision); “Precision Pinch Controller” that generates parallel thumb–index motions via Jacobian pseudoinverse; ROS/MoveIt integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable point-cloud perception; SKU/object classification to drive mode selection; consistent friction at fingertips; light lateral disturbances within trained bounds.

- Delicate food handling in packaging and prep — sectors: food & beverage, retail kitchens, commissaries

- What: Gentle pinch of deformable items (bread slices, asparagus) and stable power grasps (pan handles) on the same hand without swapping end-effectors.

- Tools/products/workflows: Task recipes that sequence precision then power grasps (e.g., pick asparagus then move pan); camera-only ACT/DexSimple policies trained on modest demos.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Food-safe, washable fingertip materials; compliance with hygiene standards; calibrated force/position control to avoid over-pressing.

- Electronics sub-assembly staging — sectors: electronics assembly, battery manufacturing

- What: Place nuts on bolts/pegs, insert cylindrical cells into holders/chargers where force and alignment must be precise but torqueing is minimal.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Peg/Groove Pinch Skill” templates with Jacobian-based parallel motion and overshoot poses; quality gates (vision checks) for seated/latched state.

- Assumptions/dependencies: No requirement for threading/torque (beyond scope); precise camera calibration and bolt/slot detection; consistent tolerances.

- Lab automation: handling small labware — sectors: biotech/pharma R&D labs, diagnostics

- What: Pinch-lift-and-place microtubes, slides, small caps in trays with reduced risk of slips or crushing, using a single dexterous hand.

- Tools/products/workflows: Dataset of labware geometries; low-shot ACT policies trained on teleop demonstrations using the pinch controller; safe speed/force limits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cleanable/chemical-resistant fingertip covers; reliable detection of clear/translucent objects; contamination control procedures.

- Teleoperation enhancement for data collection and on-the-loop execution — sectors: robotics R&D, remote operations, education

- What: Use the optimized thumb–index pinch controller in teleop to improve precision grasp demos and reduce operator fatigue (mapping fingertip distance to pinch aperture).

- Tools/products/workflows: Teleop UI plugin; retargeting module that toggles between normal and pinch modes; logging pipeline for ACT/DexSimple training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Low-latency teleop; hand–arm kinematic mapping; basic operator training.

- Simulation-driven end-effector quick design service — sectors: robotics OEMs/integrators, contract manufacturing

- What: Offer a cloud or offline service that takes a hand model and target object set, runs the neural-physics surrogate, and outputs optimized fingertip covers.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Neural Physics Surrogate SDK” (PointNet+MLP) with batch object sampling; design scoring dashboard (success probability, manipulability); STL export.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Representative object point clouds; licensing for simulator assets; periodic recalibration if the object mix drifts.

- Education and academic labs: co-design + sim-to-real teaching kits — sectors: education, academic research

- What: A turnkey pipeline demonstrating control–design co-optimization on commodity hands; repeatable benchmarks (with lateral disturbance forces).

- Tools/products/workflows: Course labs that include the switcher, pinch controller, differentiable surrogate optimization, and sim-to-real evaluation harness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to a multi-fingered hand; 3D-printing capability; open-source policy weights or small demo sets for re-training.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require additional research, scaling, integration with tactile/force sensing, or regulatory approval.

- Flexible fine-assembly cells (connector insertion, wire routing, screw starting) — sectors: electronics, automotive, appliances

- What: Move beyond placement to contact-rich insertions and initiating threads; automatic switching across dexterous primitives.

- Tools/products/workflows: Tactile-integrated pinch controller; impedance control; learned contact models; richer co-design (curved/structured fingertip geometries).

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-fidelity tactile sensing; force-limited controllers; tighter calibration and uncertainty handling.

- General-purpose household assistants with safe dexterity — sectors: consumer robotics, smart home

- What: Home tasks mixing power and precision (organizing small items, battery swaps, light cooking prep) on humanoids/mobile manipulators.

- Tools/products/workflows: Household object mode-switch datasets; safety-certified fingertip materials; continual-learning loops for new objects.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust perception in clutter; safety and privacy compliance; long-term wear resistance of covers.

- Healthcare and assistive robotics for delicate item handling — sectors: healthcare, eldercare, rehabilitation

- What: Handling medications, packages, garments with gentle pinches; preparing simple items without damage.

- Tools/products/workflows: Clinically validated pinch behaviors; easy-clean, sterilizable, or disposable fingertip covers; task-specific policies with guardrails.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory approvals (e.g., FDA/CE); strict hygiene protocols; redundant safety layers and human-in-the-loop oversight.

- Adaptive or reconfigurable fingertip surfaces — sectors: robotics hardware, materials

- What: Fingertips that change geometry or compliance on demand (e.g., adjustable planes, soft morphing pads) to widen the precision–power envelope.

- Tools/products/workflows: Real-time co-design-in-the-loop that updates geometry parameters; embedded sensing to close the loop.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Mature variable-stiffness/morphing materials; fast, safe actuation; co-optimization that runs online.

- Autonomously generated end-effector variants per SKU and per line — sectors: manufacturing, logistics

- What: MLOps for gripper design—continuous redesign and print of fingertip covers as product mix changes; automated validation in simulation-in-the-loop.

- Tools/products/workflows: Design CI/CD; digital warehouses of validated geometries; rapid post-processing and QA of printed parts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable print farms; lifecycle management for wear; governance for change control.

- Humanoid manipulation in retail and back-of-house operations — sectors: retail, hospitality

- What: Restocking and organizing small, deformable, and boxed items with a single hand that fluidly shifts between precision and power grasps.

- Tools/products/workflows: Shelf-aware grasp mode switchers; SKU-specific policies; safety envelopes for operation near people.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust navigation and perception stacks; compliance with occupational safety standards.

- Standards and policy: dexterity benchmarks and safety metrics for general-purpose hands — sectors: policy, industry consortia

- What: Establish test suites (including lateral disturbance forces) for precision grasp reliability, damage avoidance, and mode-switch correctness.

- Tools/products/workflows: Open benchmarks and scoring protocols; reference tasks (e.g., “bread pinch,” “nut-on-peg”); certification programs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder coordination; reproducible test hardware; agreement on metrics and thresholds.

- High-reliability telerobotics in hazardous domains — sectors: nuclear, chemical, space

- What: Remote manipulation of small vials, valves, and connectors with precision pinches; reduced task failure due to better contact geometry.

- Tools/products/workflows: Hardened teleop stack with pinch controller; radiation/temperature-resistant covers; redundancy and fault detection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Extreme reliability requirements; environmental compatibility; rigorous operator training.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Perception: The switcher and policies assume reliable point-cloud or RGB-D sensing, object segmentation, and calibrated hand–eye transforms.

- Control: Accurate Jacobians and joint tracking; stable low-level controllers; optionally, force/impedance control for contact-rich tasks.

- Materials and wear: Fingertip cover friction and durability strongly influence success; periodic inspection and replacement may be required.

- Sim-to-real gap: The reported robustness benefits from flat-plane contacts and parallel motions; large domain shifts (lighting, surfaces, object friction) still require adaptation.

- Safety and compliance: Human-facing deployments need speed/force limits, fail-safes, and appropriate certifications (especially in food and healthcare settings).

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.