SPIDER: Scalable Physics-Informed Dexterous Retargeting (2511.09484v1)

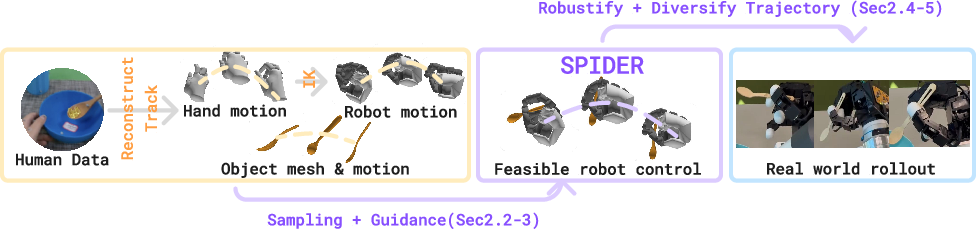

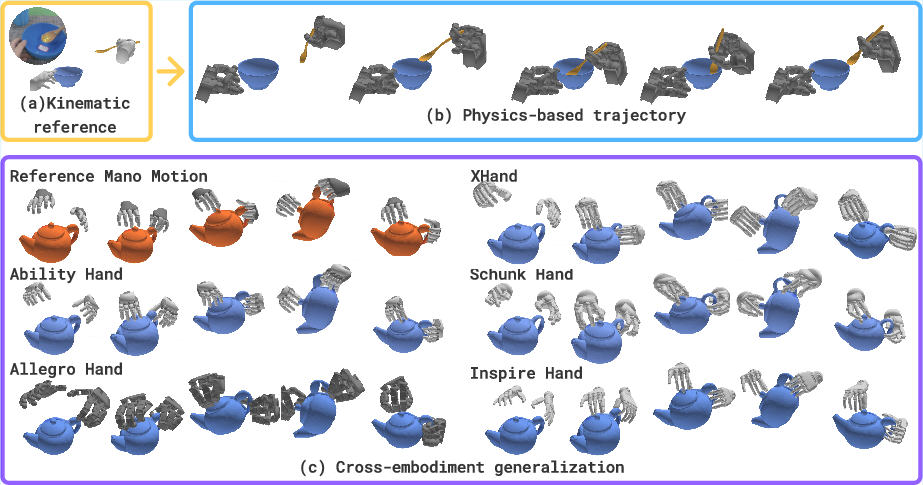

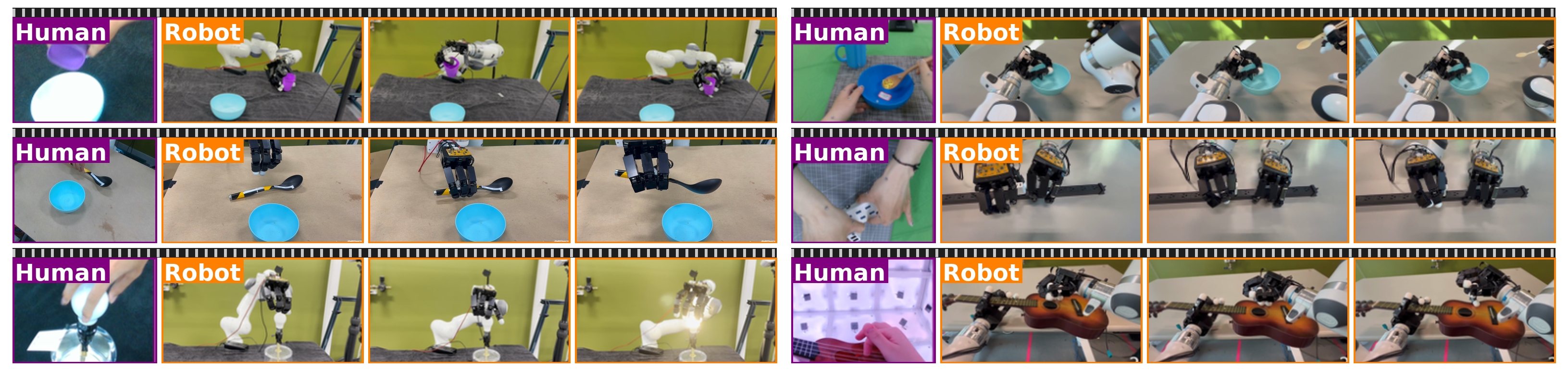

Abstract: Learning dexterous and agile policy for humanoid and dexterous hand control requires large-scale demonstrations, but collecting robot-specific data is prohibitively expensive. In contrast, abundant human motion data is readily available from motion capture, videos, and virtual reality, which could help address the data scarcity problem. However, due to the embodiment gap and missing dynamic information like force and torque, these demonstrations cannot be directly executed on robots. To bridge this gap, we propose Scalable Physics-Informed DExterous Retargeting (SPIDER), a physics-based retargeting framework to transform and augment kinematic-only human demonstrations to dynamically feasible robot trajectories at scale. Our key insight is that human demonstrations should provide global task structure and objective, while large-scale physics-based sampling with curriculum-style virtual contact guidance should refine trajectories to ensure dynamical feasibility and correct contact sequences. SPIDER scales across diverse 9 humanoid/dexterous hand embodiments and 6 datasets, improving success rates by 18% compared to standard sampling, while being 10X faster than reinforcement learning (RL) baselines, and enabling the generation of a 2.4M frames dynamic-feasible robot dataset for policy learning. As a universal physics-based retargeting method, SPIDER can work with diverse quality data and generate diverse and high-quality data to enable efficient policy learning with methods like RL.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces SPIDER, a method that turns human movements (like using a spoon, pouring tea, or walking) into robot actions that actually work in the real world. It focuses on tasks where things touch each other a lot (called “contact-rich” tasks), like a robot hand grasping an object or a humanoid robot’s feet staying on the ground while running. The big idea is to use physics and smart search to convert human motion into robot motion that matches the robot’s body and obeys the laws of physics.

What questions does the paper try to answer?

The paper asks a simple but important question: How can we efficiently and reliably transform human motion into robot actions that are physically possible and keep the important contacts (like where fingers hold an object)?

In everyday terms:

- Humans and robots have different “bodies” (shape, joints, strength). How do we translate a human action to fit a robot?

- How do we make sure the robot doesn’t “cheat” by sliding through objects or floating—things that would be impossible in the real world?

- How can we do this fast and at large scale using lots of human motion data (videos, motion capture)?

How does SPIDER work? (Explained simply)

Think of retargeting like tailoring a dance or a trick: you watch a human perform it, then “tailor” it so a robot with a different build can perform a similar motion.

SPIDER does this in four main steps:

- Building a reference motion

- From videos or motion-capture data, the system reconstructs the human’s movement and the object’s movement (where everything is in 3D over time). This is the “reference” the robot should follow.

- Physics-based optimization (using simulation)

- The robot can’t just copy the movement: its fingers, arms, and legs are different. SPIDER uses a physics simulator to check whether a robot’s attempt is realistic (no slipping, correct forces, proper contacts).

- It tests many slightly different versions of the robot’s action sequence and scores them based on two things:

- How well the object and robot end up where they’re supposed to be (matching the reference)

- Whether the motions obey physics (no clipping, correct contact, feasible forces)

- Sampling with annealing (try many, then zoom in)

- “Sampling” means trying a lot of possible action sequences.

- Annealing is like starting with big, bold changes to explore widely, then making smaller tweaks as you get closer to a good solution.

- Imagine searching for a treasure: at first you wander widely, then you zoom in and walk carefully once your detector starts beeping louder.

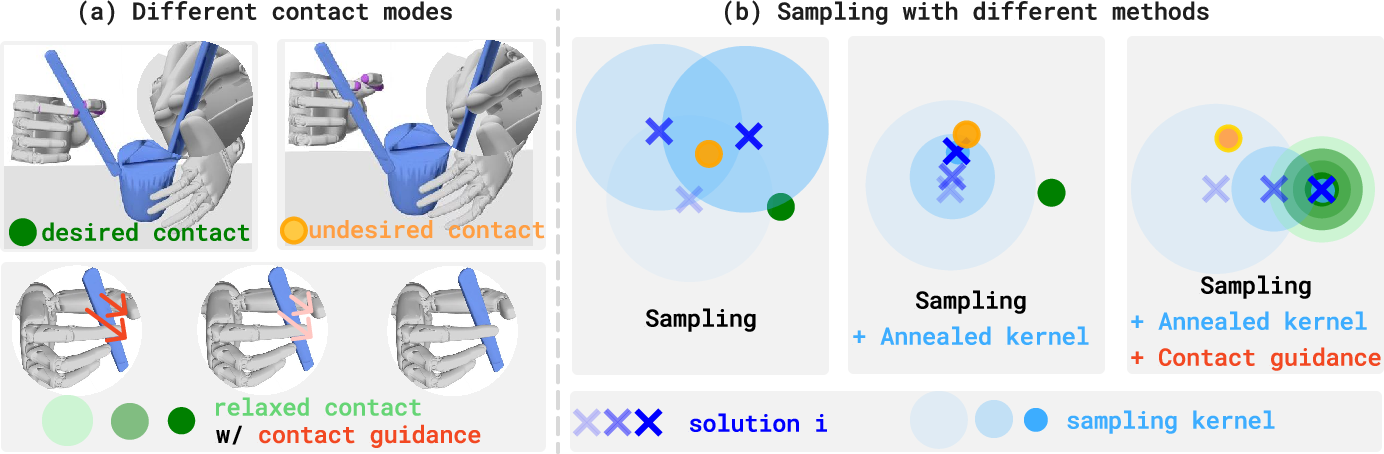

- Virtual contact guidance (temporary “sticky” helpers)

- In contact-rich tasks, there may be multiple ways to do the job (e.g., hold a stick between thumb–index or index–middle finger).

- SPIDER adds a gentle, temporary “sticky” force (like a weak magnet or light glue) between the intended contact points (e.g., thumb and the stick handle) to guide the robot toward the human’s preferred contact style.

- This “sticky” help is slowly removed as the robot finds and stabilizes the right contact.

Extra: Making plans sturdy for the real world (robustification)

- Real robots face small differences: friction, weight, slight errors in object shape.

- SPIDER practices under different possible conditions (like training in rain, sun, or wind) and optimizes for the worst case, so the final plan is sturdy.

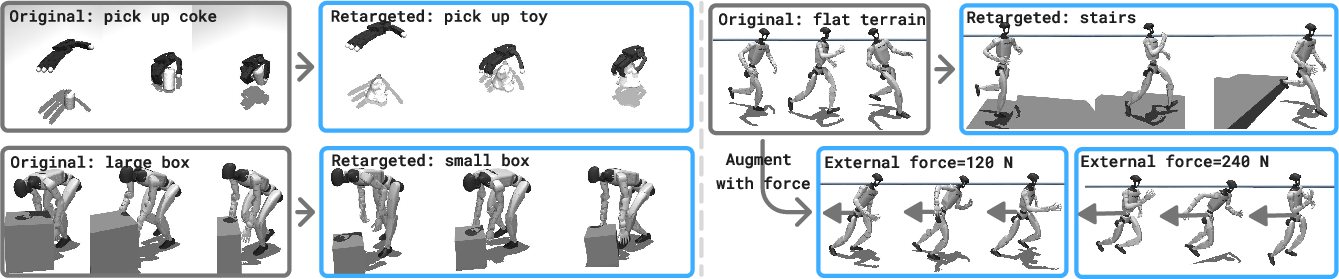

Bonus: Physics-based data augmentation

- Starting from one human demo, SPIDER can make many new, realistic variations:

- Change the object (e.g., from a soda can to a toy)

- Change its size or initial location

- Change the terrain (add stairs)

- Add external forces (someone tugging on the robot)

- This creates lots of useful training data for future learning.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Key results:

- Preserves intended contacts: The “virtual contact guidance” helps the robot use contact in the same way humans do (for example, the same fingers on the same part of an object).

- Faster than many learning-based methods: SPIDER generates usable robot trajectories much faster—about 10 times quicker than some reinforcement learning approaches—because it directly optimizes actions instead of training a policy.

- Scales across many robots and tasks: It works on different robot hands (with different finger shapes and numbers) and on humanoid robots doing locomotion and object interaction.

- Improves success rates: Compared to a strong sampling baseline, adding contact guidance increases success by around 18%.

- Works in the real world: The authors ran SPIDER’s trajectories on a real robot arm with a robot hand to do precise tasks (like rotating a light bulb, picking up a spoon, unplugging a charger, playing guitar). That shows the plans aren’t just good in simulation—they also work in real life.

- Fixes common kinematic problems for humanoids: For walking/running data, SPIDER removes foot sliding and penetration by grounding the motion in physics, improving tracking accuracy.

Why it matters:

- We have tons of human motion videos and motion-capture data. SPIDER can turn this into useful robot actions, closing the gap between what humans do and what robots can learn.

- It makes building large datasets of robot-friendly trajectories easier, which helps train better robot controllers and policies.

- It handles “contact-rich” manipulation—one of the hardest parts of robotics—more reliably and in a way that captures human intent.

What’s the impact and what could this lead to?

- Faster robot learning: By quickly generating lots of realistic, physics-checked trajectories, SPIDER can jump-start reinforcement learning or imitation learning, cutting time and cost.

- Better generalization: Because SPIDER works across many robot bodies and object types, it helps robots adapt to new tasks and setups without starting from scratch.

- More natural robot behavior: By keeping human-like contact patterns, robots can manipulate objects in ways that look and feel right—important for delicate tasks and human-robot interaction.

- Bridging sim-to-real: Robustification means plans survive the jump from simulation to real hardware—critical for actually deploying robots.

- Scaling to internet-sized data: As computer vision recovers 3D motion from videos more reliably, SPIDER can convert massive human datasets into robot actions at scale.

In short, SPIDER is like a smart translator—and a coach—that takes human movement and turns it into physically correct, contact-aware robot motion, quickly and at large scale. This could make future robots more capable, more adaptable, and much easier to teach using the vast amount of human motion data already available.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper; each item is framed to be actionable for future research.

- Reliance on accurate 3D reconstructions: the pipeline assumes reasonably accurate human pose, hand pose, object mesh, and 6D object trajectories; robustness to large reconstruction errors, occlusions, and cluttered scenes is not quantified.

- No joint estimation of physical parameters: object mass, friction, and contact compliance are randomized but not identified; integrating parameter estimation from demonstrations or online identification is unexplored.

- Contact mode acquisition is heuristic: “virtual contact guidance” hinges on detecting desired contact pairs via proximity and duration thresholds; automatic, robust inference of contact semantics from noisy/different embodiments is not addressed.

- Contact fidelity metrics are missing: there is no quantitative evaluation of whether retargeted contact modes match human contact sequences (e.g., contact point sets, durations, modes); defining and tracking a contact-similarity metric is open.

- Alternative feasible contact modes are not leveraged: the framework biases toward the human-preferred mode; principled discovery and selection among multiple feasible robot-specific grasps/modes remains unexplored.

- Limited handling of in-hand regrasping and finger gaiting: tasks requiring discrete contact switches and dexterous regrasp plans are not explicitly modeled; integrating discrete contact planning with sampling is open.

- Virtual guidance scheduling is hand-tuned: how to adaptively schedule the strength/activation of virtual constraints based on stability, progress, or uncertainty is not studied.

- Risk of enforcing infeasible contacts: when human contacts are incompatible with robot morphology (e.g., missing thumb), the method may overconstrain the optimizer; automatic remapping or substitution of contact targets is not provided.

- Contact stability is not explicitly enforced: the objective uses relative pose penalties; guarantees on force closure, friction cones, and slip avoidance are not incorporated.

- Dynamics limits are under-specified: torque/velocity/force limits and joint coupling (e.g., tendon-driven hands) are simplified or removed in simulation; ensuring feasibility under real hardware constraints remains open.

- Simulator fidelity and cross-engine validity are unassessed: sensitivity to the chosen physics engine, contact models, and time-stepping is not analyzed; cross-simulator validation is missing.

- Open-loop deployment only: real-robot executions are open-loop with offline robustification; the benefits of online closed-loop MPC/replanning with contact guidance are not evaluated.

- Real-time feasibility is limited: trajectory generation at ~2.5 Hz is below typical control rates; achieving real-time (50–200 Hz) with comparable quality is an open engineering and algorithmic challenge.

- Hyperparameter tuning is ad hoc: annealing parameters, temperature λ, cost weights Q/R, and robustification ranges lack principled selection; automated/meta-learned tuning or Bayesian optimization is unexplored.

- Proposal distribution is not learned: sampling uses Gaussian noise; learning better trajectory proposals (e.g., diffusion models, learned MPPI kernels) to reduce samples and improve convergence is an open direction.

- No theoretical guarantees: convergence properties, optimality bounds, and sample complexity for the annealed sampling with virtual constraints are not analyzed.

- Humanoid contact scheduling is simplified: only foot–ground contacts are guided; automatic discovery and enforcement of multi-contact schedules (hands, knees, hips) for whole-body tasks is not addressed.

- Articulated and deformable objects are out of scope: the approach assumes rigid bodies; extension to articulated mechanisms (doors, tools), deformables (cloth), or fluid interactions is unexplored.

- Bimanual coordination specifics are unclear: synchronization constraints, inter-hand contact reasoning, and role assignment in two-hand tasks are not explicitly modeled or ablated.

- Evaluation focuses on object tracking: task success is defined by pose errors; grasp stability, force regulation, slippage, and safety metrics are absent.

- Limited benchmarking breadth: comparisons to contact-invariant optimization, hybrid TO/MPC, or recent differentiable physics-based retargeting methods are missing; only select RL baselines are reported and on small subsets.

- Failure mode analysis is sparse: the causes of failures on ARCTIC (e.g., complex regrasp, contact ambiguity, tight tolerances) are not dissected; diagnostic tools and per-factor sensitivity ablations are needed.

- Perception–control integration is not addressed: the pipeline presumes known object pose/mesh at deployment; robustness to online perception noise and delayed/partial observations is untested.

- Domain randomization bounds lack justification: the chosen ranges for friction, mass, and contact parameters are not derived from real measurements; systematic calibration or uncertainty quantification is open.

- Data augmentation utility is unquantified: while physics-based augmentations are demonstrated, their impact on downstream policy learning/generalization is not evaluated.

- Human-preference modeling is implicit: “naturalness” of contacts is enforced via virtual guidance; learning priors over contact modes from large human datasets and trading off task success vs. naturalness remains open.

- Embodiment-aware remapping is limited: beyond object-centric costs, learning a principled mapping between human kinematics and diverse robot morphologies is not tackled.

- Energy and compute cost reporting is incomplete: GPU/CPU budgets, memory footprints, and throughput for internet-scale retargeting are not detailed; scaling limits and carbon/compute costs are unclear.

- Robustness to large domain shifts is untested: generalization from curated mocap/AR datasets to unconstrained internet videos with variable lighting, backgrounds, and camera motion is not shown.

- Safety constraints are not explicit: ensuring contact forces and joint torques remain within safe limits for hardware during optimization and execution is not guaranteed.

- Dataset and code release details are unclear: exact splits, preprocessing scripts, and reproducibility artifacts (versions, seeds) are not specified; end-to-end replicability from raw data to trajectories is uncertain.

- Object-set generalization: replacing meshes is shown qualitatively; systematic analysis of success vs. shape class, size, and grasp affordances (e.g., handles vs. smooth bodies) is missing.

- Contact-filter thresholds are heuristic: the choices of t_c,min and d_c,max and their sensitivity are not justified; adaptive or learning-based contact-quality estimators are an open avenue.

Glossary

- Annealed sampling kernel: A noise-sampling mechanism whose covariance shrinks over iterations and along the horizon to balance exploration and refinement when optimizing control sequences. "we adopt a sampling-based optimizer with an annealed sampling kernel"

- Annealing schedule: A time-varying rule that decreases sampling covariance during optimization to move from coarse search to fine refinement. "Annealing schedule for sampling covariance"

- Basin of attraction: The region of initial conditions in which an optimizer converges to a particular solution; enlarging it makes the desired solution easier to find. "explicitly enlarges the basin of attraction to make it easier to sample from"

- Bimanual manipulation: Tasks that involve coordinated use of two hands to interact with one or more objects. "3 bimanual manipulation datasets"

- Contact compliance: The deformability or softness in contact interactions that affects force transmission and stability. "friction, contact compliance"

- Contact mode: A discrete pattern describing which parts are in contact (e.g., which fingers touch an object), often leading to multiple feasible ways to accomplish a task. "Contact mode mismatch in sampling and virtual guidance method to correct it."

- Contact-rich manipulation: Tasks characterized by frequent, sustained, or complex contacts that make optimization highly non-smooth. "In contact-rich dexterous manipulation, the feasible solution set is typically narrow"

- Cross-embodiment retargeting: Transferring motions across agents with different bodies, morphologies, or actuation systems. "physics-based cross-embodiment retargeting"

- Degrees of Freedom (DoF): The number of independent variables (e.g., joints) that define a robot’s configuration. "12-DoF configuration"

- DIAL-MPC: A sampling-based model predictive control method that anneals noise over time to improve efficiency and convergence. "similar to DIAL-MPC"

- Domain randomization (DR): A robustness technique that varies environment or dynamics parameters during optimization or training to improve transfer. "domain randomization (DR) method"

- Dynamical feasibility: The property of a trajectory or control sequence being consistent with the system’s physics and actuation limits. "ensure dynamical feasibility and contact correctness."

- Early stopping: A procedure that halts optimization when further iterations yield negligible improvement to save computation. "we adopt an early stopping strategy"

- Embodiment gap: The mismatch in morphology, dynamics, and actuation between humans and robots that complicates motion transfer. "the embodiment gap - the mismatch in morphology, dynamics, and actuation between humans and robots - which leads to infeasible motion during transfer."

- Exploration–exploitation trade-off: The balance between broad search for new solutions and focused refinement of promising ones. "implements this exploration-exploitation trade-off"

- GPU parallelization: Utilizing graphics processors to execute many simulation rollouts or computations simultaneously for speed. "leverages GPU parallelization through batched rollouts"

- Humanoid whole-body control: Coordinated control of an entire humanoid robot, including locomotion and manipulation with arms, legs, and torso. "humanoid whole-body control"

- Inverse kinematics (IK): Computing joint configurations that achieve desired end-effector poses without explicitly considering dynamics. "inverse-kinematics (IK) approaches"

- Kinematic retargeting: Transferring motion at the pose/geometry level (often via IK) without enforcing dynamic consistency. "Kinematic retargeting: fingertip inverse kinematics as an initial-guess quality baseline;"

- Min–max objective: A robust optimization criterion that minimizes the worst-case cost over a set of uncertain parameters. "a pessimistic (min--max) objective"

- MPPI: A sampling-based control algorithm (Model Predictive Path Integral) that optimizes actions via stochastic rollouts and importance weighting. "Standard sampling (e.g. MPPI)"

- Non-convex optimization landscape: An objective surface with many local minima and discontinuities, making global optimization challenging. "highly non-convex and often non-continuous."

- Open-loop rollout: Executing a preplanned control sequence without feedback corrections during execution. "Open-loop rollout with robustification."

- Operational Space Control (OSC): A control framework that regulates motion and force in task space (e.g., end-effector space) rather than joint space. "operational space control (OSC)"

- Prediction horizon: The time window over which future states and controls are planned or sampled in model predictive methods. "along the prediction horizon"

- Quaternion: A four-parameter representation of 3D rotation used for smooth, singularity-free orientation tracking. "object quaternion"

- Reinforcement learning (RL): Learning control policies by maximizing expected rewards through trial-and-error interactions in simulation or the real world. "reinforcement learning (RL) approaches"

- Robustification: Techniques to make trajectories or controllers reliable under dynamics/model uncertainties and noise. "we introduce a robustification strategy"

- Sampling-based optimization: An approach that searches for good solutions by stochastically perturbing and evaluating candidate control sequences via simulation. "Sampling-based optimization provides a natural way to handle such landscapes"

- SE(3): The Lie group of 3D rigid-body poses combining rotation and translation. "q\text{ref,object}_{t} \in \mathrm{SE}(3)"

- State transition function: The dynamics mapping that predicts the next state from the current state and control input. "x_{t+1} = f(x_t, u_t, t) is the state transition function"

- Teleoperation: Controlling a robot remotely by a human operator, often to collect demonstrations or perform tasks directly. "teleoperation is dynamically feasible but often labor-intensive and embodiment-specific."

- Trajectory rollout: Simulating the evolution of the system over time under a candidate control sequence to evaluate cost or feasibility. "by simulation rollout"

- Virtual contact guidance: A temporary, gradually relaxed constraint that “sticks” intended contact pairs to bias sampling toward desired contact modes. "we introduce virtual contact guidance."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable use cases that leverage SPIDER’s sampling-based, physics-informed retargeting and virtual contact guidance to turn human motion into dynamically feasible robot trajectories.

- Robotics data generation at scale for manipulation and humanoids (robotics, software/ML, academia)

- Use SPIDER to convert existing human-motion datasets (e.g., GigaHands, OakInk, AMASS/LAFAN1/OMOMO) into robot-feasible demonstrations across multiple embodiments (e.g., Allegro, Schunk, Unitree G1/H1-2), including physics-aware augmentations (new objects, scales, terrains, external forces).

- Tools/products/workflows: “Retarget-then-train” pipelines for IL/RL/VLA models; dataset curation tools; MuJoCo/Isaac Gym retargeting jobs; nightly data augmentation services.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Simulatable scenes (robot URDFs, object meshes); adequate 3D reconstructions of human/object trajectories; GPU access for parallel simulation; data licensing for source videos/mocap.

- Fast bootstrapping of manipulation policies from demonstrations (robotics, software/ML)

- Seed RL/IL policies with SPIDER-generated, contact-correct demonstrations; lower reward-engineering effort and improve sample efficiency.

- Tools/products/workflows: Replay buffers with physics-grounded demos; curriculum generation by scene/object physics variations; training scripts that interleave SPIDER demos with online rollouts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Simulator–hardware dynamics gap mitigated by robustification (domain randomization ranges, contact parameters); policy architectures that accept trajectory supervision.

- Simulation-first safety and feasibility checks for contact-rich tasks (industry/manufacturing, warehousing, field service)

- Validate planned contact sequences (e.g., insertion, unscrewing, unplugging, pouring) with object-centric guidance before on-robot execution; reduce trial-and-error on shop floors.

- Tools/products/workflows: Preflight “physics feasibility” checks in digital twins; ROS action servers that accept human videos and output validated motion scripts; gating criteria based on object-tracking error and contact stability.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate friction and compliance ranges; calibration of robot base and end-effector relative to scene; safe execution monitors.

- Program-by-demonstration from human videos for common lab tasks (academia, R&D labs, robotics startups)

- Translate human manipulation videos into deployable dexterous scripts for bimanual/hand-arm platforms; replicate tasks like rotating a bulb, unplugging a charger, picking a spoon, pouring.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Video-to-trajectory” assistants for lab techs; internal skill libraries organized by object families; task parameterization by object mesh or scale.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality of human pose/object tracking; initial grasp/contact inferred or scripted; operator approvals and safety constraints for open-loop execution.

- Humanoid motion retargeting with contact correction (entertainment robotics, humanoid R&D)

- Produce physically consistent gaits and dances (remove foot sliding/penetration) for varied humanoids using virtual foot-floor guidance; previsualize motions prior to hardware demos.

- Tools/products/workflows: Studio tools to import mocap and export feasible joint trajectories for specific humanoids; animation-to-robot pipeline integrations (e.g., Blender/Unreal → SPIDER → ROS).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Humanoid models and actuator limits; ground properties; accurate pelvis/feet reference trajectories.

- Reduced teleoperation burden for demonstration collection (robotics, operations)

- Convert large volumes of human motion into robot-feasible demos instead of collecting extensive teleop sessions; reserve teleop for edge cases.

- Tools/products/workflows: Hybrid demo ingestion (VR, mocap, video recon) into a unified retargeting queue; prioritization by expected feasibility.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Coverage of common contact modes via virtual contact guidance; per-task thresholds for acceptable object-tracking error.

- Benchmarking and analysis of contact modes across embodiments (academia)

- Study contact ambiguities and contact-mode preservation using SPIDER’s virtual guidance; evaluate success tradeoffs vs. annealing schedules.

- Tools/products/workflows: Open evaluation suites for contact-mode fidelity; ablation tools for annealing/contact filters; cross-hand generalization studies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consistent metrics (object pose error, success thresholds); reproducible simulation settings.

- Physics-based data augmentation for robustness (robotics, software/ML)

- From a single human demo, generate variations across object shape/size/pose, terrains (e.g., stairs vs flat), and external disturbances; create robust training corpora.

- Tools/products/workflows: “One-to-many” augmentation services; domain randomization profiles; difficulty curriculum management.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Valid physics parameter ranges; coverage of plausible contact sequences; stability filters to reject noisy/unstable guidance contacts.

- On-robot deployment of validated trajectories for simple to moderate tasks (robotics integrators, advanced labs)

- Execute robustified open-loop scripts for short, well-bounded tasks demonstrated in the paper (e.g., light bulb rotation, unplugging cables) on platforms like Franka + Allegro.

- Tools/products/workflows: Task launchers with fail-safes; action-state monitors; parameterized object detection and pose alignment before execution.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate alignment of scene to simulation; emergency stops; mechanical compliance and collision monitoring; preference for short horizon tasks.

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities require additional research, scaling, hardware maturity, or integration work before broad deployment.

- Internet-scale training of generalist robot models from human videos (software/ML, robotics)

- Leverage SPIDER to convert massive web-scale human-object interaction videos into physics-feasible robot data for VLA/foundation models; close the embodiment gap at scale.

- Tools/products/workflows: Cloud “retargeting farms” attached to data lakes; automated reconstruction (pose/object meshes/trajectories) and quality filters; continual data curation loops.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable 3D reconstruction from unconstrained videos; robust legal/licensing pipelines; scalable simulators; automated contact-mode inference.

- Home assistive robots that learn from user’s phone videos (healthcare/assistive tech, consumer robotics)

- Personalize household skills (opening containers, arranging items, appliance manipulation) from end-user recordings; adapt across object variants via physics augmentation.

- Tools/products/workflows: Companion apps for “record-and-teach”; cloud retargeting + on-device verification; per-home digital twins for safety checks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust perception in clutter; low-cost yet dexterous end-effectors; strict safety policies; reliable object recognition and pose estimation.

- Rapid, one-shot program-by-demonstration for assembly and maintenance (manufacturing, energy, construction)

- Convert SMEs’ demonstrations (AR/VR/mocap/video) into contact-validated robot procedures for valves, clamps, fasteners, cabling, panel operations across new SKUs and fixtures.

- Tools/products/workflows: Integration with PLM/CAD and factory digital twins; automated fixture registration; per-SKU contact templates; change-over automation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate CAD-to-reality registration; compliance strategies for tight tolerances; certification and interlocks for safety; versioned skill libraries.

- Real-time cross-embodiment telepresence with physics-informed stabilization (defense, disaster response, nuclear)

- Map human motions to humanoids/dexterous arms in real time with on-the-fly sampling and virtual guidance to stabilize contacts in uncertain environments.

- Tools/products/workflows: Low-latency streaming + onboard GPU simulation; adaptive annealing schedules; predictive safety envelopes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Further speedups in sampling and simulation; robust communication; hardened hardware; operator training.

- Surgical and clinical skill transfer (healthcare)

- Retarget expert hand motions (from simulators or teleop logs) into robot-feasible trajectories for training, rehearsal, and assistive execution with accurate contact handling.

- Tools/products/workflows: Hospital-grade digital twins of anatomy/tools; preop rehearsal with robustification; skill assessment metrics tied to contact quality.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory approval; ultra-high-fidelity tissue/tool models; stringent safety, latency, and explainability requirements.

- Personalized prosthetics and exoskeleton control (healthcare)

- Translate contralateral or therapist demonstrations into prosthetic/exoskeleton control trajectories; adapt contact strategies (grasp types, load sharing) through virtual guidance.

- Tools/products/workflows: Co-adaptive training loops combining EMG/IMU with retargeted references; prosthetic calibration wizards; task-specific grasp libraries.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust sensor fusion; comfort and safety constraints; per-user customization; real-time constraints.

- Retargeting-as-a-Service platforms (software, robotics ecosystem)

- Offer APIs where developers upload human demos (video/mocap/VR) and receive robot-specific, physics-feasible trajectories plus augmented variants for training or execution.

- Tools/products/workflows: Multi-robot embodiment support; quota-managed GPU simulation pools; quality scoring and contact-mode diagnostics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standardized robot and object descriptors; data privacy and IP control; service-level latency and cost.

- Standards and policy frameworks for simulation-backed safety validation (policy, industry consortia)

- Codify pre-deployment simulation requirements for contact-rich manipulation and humanoid motions, including contact stability metrics, robustification ranges, and pass/fail criteria.

- Tools/products/workflows: Conformance test suites; third-party audit scripts; certification pipelines bound to digital twins.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cross-industry agreement on metrics and thresholds; validation of simulator fidelity; harmonized data governance for human-sourced motion.

- Integrated digital twins for end-to-end skill lifecycle (industry 4.0)

- Connect SPIDER with factory/site digital twins to continuously generate, validate, and update skills as products or environments change; close the loop with telemetry.

- Tools/products/workflows: Change detection triggers re-retargeting; automated A/B validation in sim; version control for skills and contact templates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Mature twin fidelity; data ops for streaming scene updates; robust sim2real pipelines.

- Entertainment and live performance with humanoids/animatronics (media/arts)

- Retarget choreographies and props interaction from dancers/actors to physical robots while ensuring contact-safe interactions with sets and instruments.

- Tools/products/workflows: Creative pipelines (mocap → SPIDER → rehearsal twin → stage control); fast iteration tools for directors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quiet, reliable actuation; stage-safe contact margins; tight iteration latency.

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- Core dependencies: high-quality 3D reconstruction of human and object motion; accurate robot models and object meshes; physics parameters (friction, compliance) within robustification ranges; GPU-parallel simulation infrastructure.

- Risk factors: noisy demonstrations (unstable contacts), large embodiment mismatches, poor scene calibration, licensing/consent for human data, and safety constraints for on-robot execution.

- Mitigations: virtual contact guidance with stability filters, min–max robustification over domain ranges, geometry/physics-aware augmentation for coverage, and staged deployment via digital twins before hardware execution.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.