- The paper finds that sharp minima discovered with large datasets can generalize well despite their small basin volumes.

- It employs Monte Carlo basin volume estimation and rigorous empirical evaluation to contrast sharp minima with flat minima.

- Results reveal a power-law decay in basin volume with increasing data, challenging traditional notions of flatness in generalization.

Sharp Minima Can Generalize: Insights from Loss Landscape and Data Dependence

Introduction

This work addresses the interplay between loss landscape volume, flatness of minima, and dataset size in deep learning generalization. Building on the volume hypothesis—which posits that minimization procedures like SGD are biased toward large-volume, hence flat, minima that generalize well—the paper scrutinizes its explanatory power in the context of varying dataset sizes and measures basin volumes empirically. The investigation reveals that sharp minima, typically smaller in parameter space, can generalize well, especially when more data transforms the loss landscape, thus challenging prevailing wisdom on flatness and generalization.

Theoretical Framework

Flat Minima vs. Volume Hypothesis

Two central hypotheses structure the analysis of generalization:

- Flat Minima Hypothesis: Minima that are flat (allowing substantial perturbations without significant loss increases) tend to generalize better, often justified via minimum description length arguments and margin theory.

- Volume Hypothesis: SGD and similar optimizers preferentially find minima with large volume in parameter space, correlating with flatness.

While empirical evidence supports both, scale invariance and layer-wise degeneracies in neural nets (see [dinh_sharp_2017]) undermine naive flatness measures. Theoretical counterexamples and numerical findings show that sharp minima can generalize, and flat minima are not universally optimal ([andriushchenko_modern_2023], [wen_sharpness_nodate]).

Monte Carlo Basin Volume Estimation

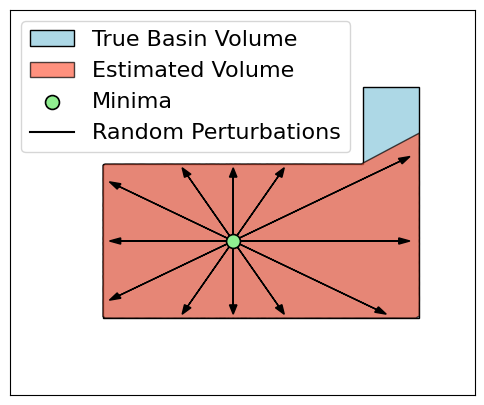

Volume is interpreted as the region in parameter space with loss below a threshold, estimated via Monte Carlo probing along random directions from the minima. The approximation integrates rn, the distance in each direction to the basin boundary, yielding:

V≊K1∑i=1Krn(θi)

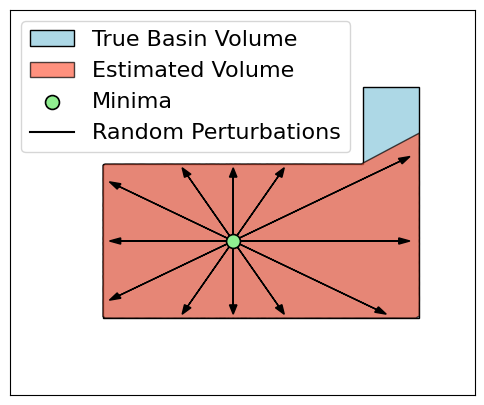

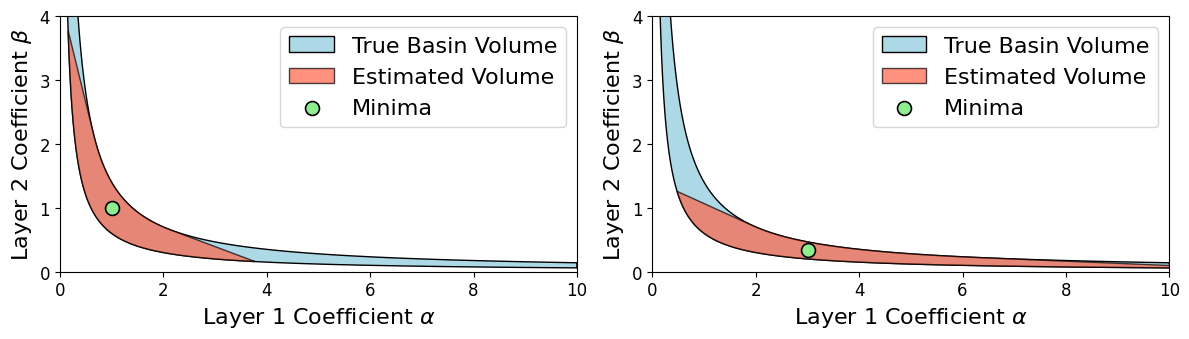

However, in high-dimensional spaces this estimate is dominated by the largest sampled radius (Figure 1), and scale invariance complicates fair comparison (Figure 2). Filter normalization and refined sampling mitigate these issues.

Figure 1: Monte Carlo basin volume estimation can underestimate actual minima volume and is sensitive to high-dimensional sampling effects.

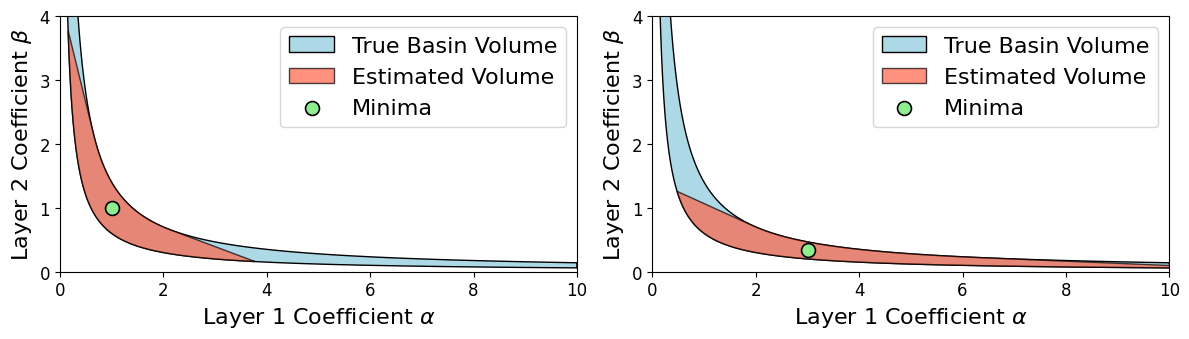

Figure 2: Layer-wise scale invariance exemplifies the challenge for flatness measures, but star-convex basin volume remains robust under rescaling.

Empirical Results

Poisoned Minima

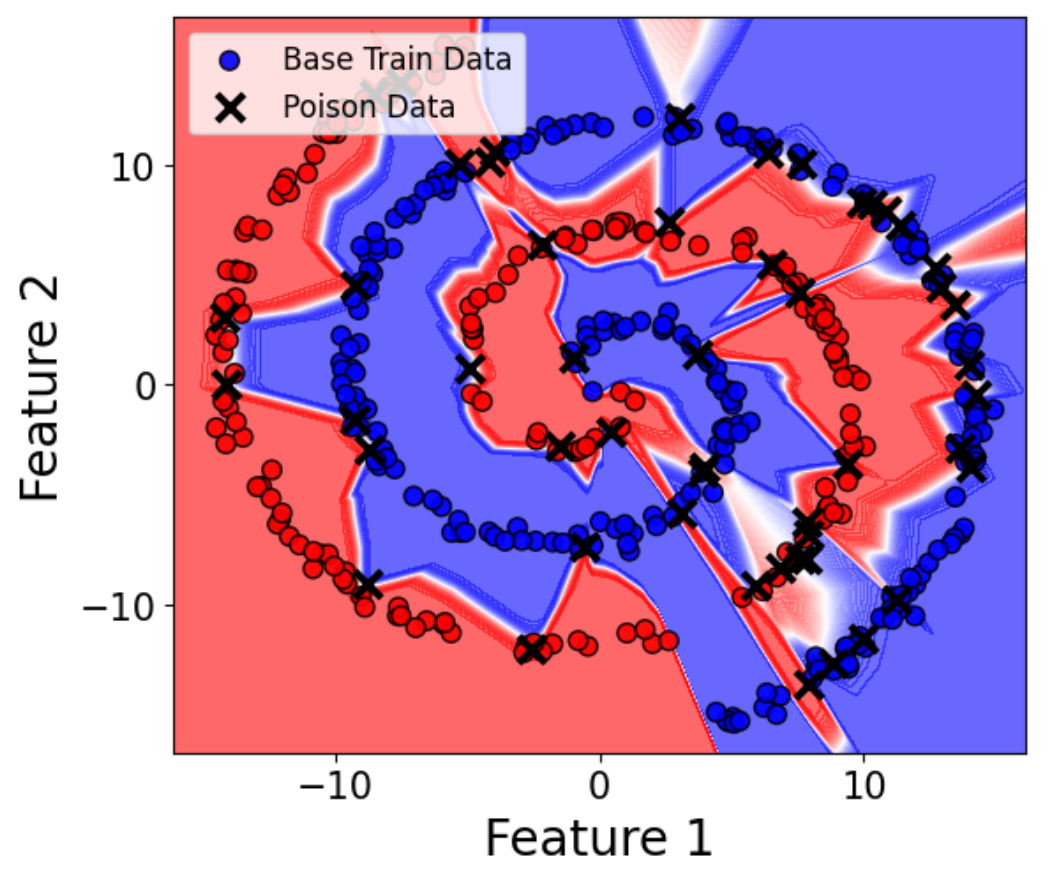

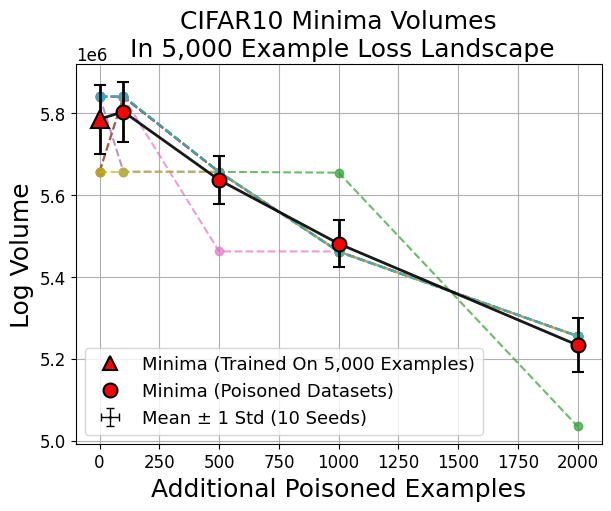

Extending prior work ([huang_understanding_2020]) to MNIST and CIFAR10, models trained on datasets with label noise ("poisoning") consistently produce minima with smaller basin volumes compared to correctly-labeled datasets, tightly correlating with poor generalization.

Figure 3: Poisoned minima (red circles) have markedly smaller basin volume than unpoisoned minima, matching their poor test accuracy.

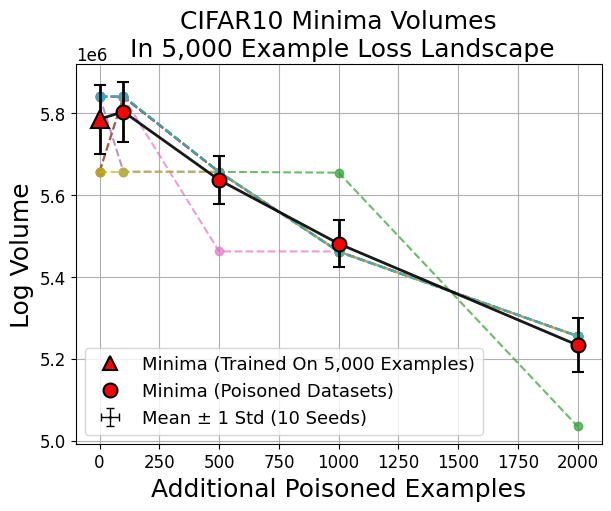

Figure 4: Basin volume reduction is robust across datasets and persists even for small degrees of poisoning.

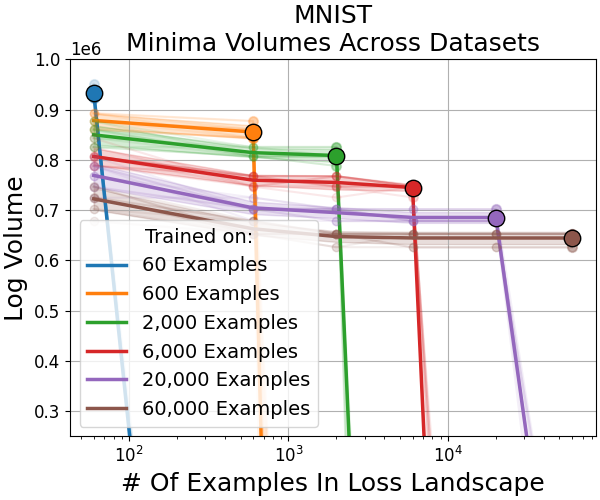

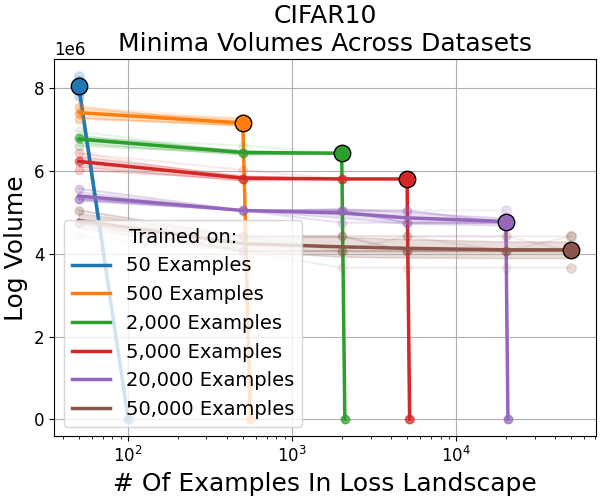

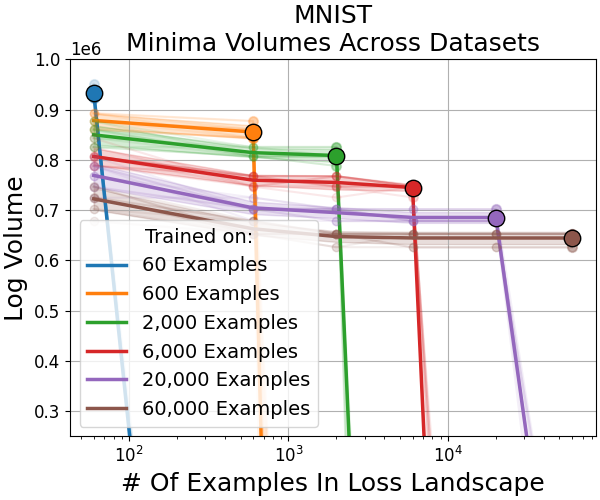

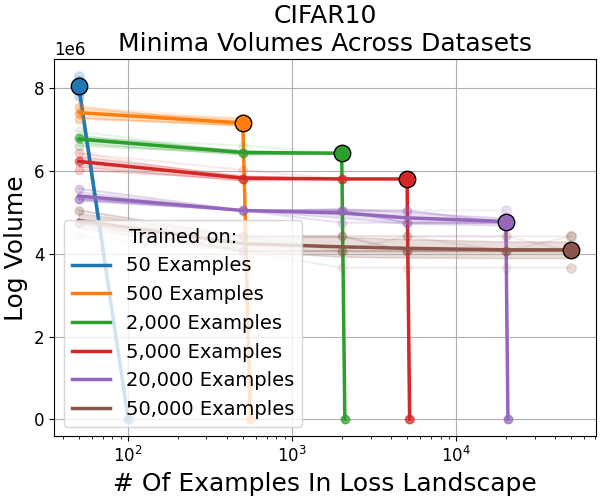

Dataset Size and Minima Volume

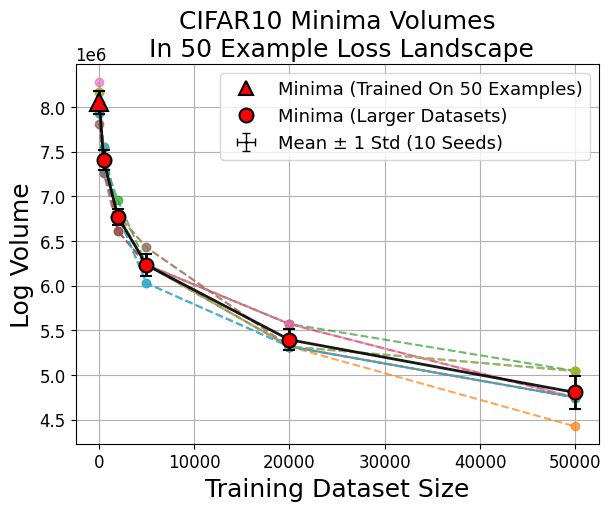

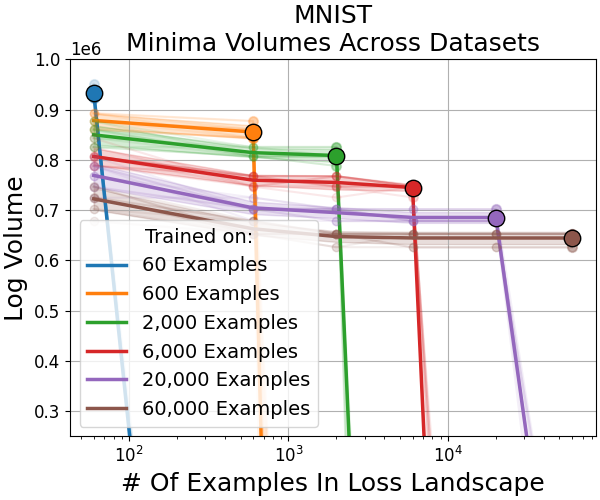

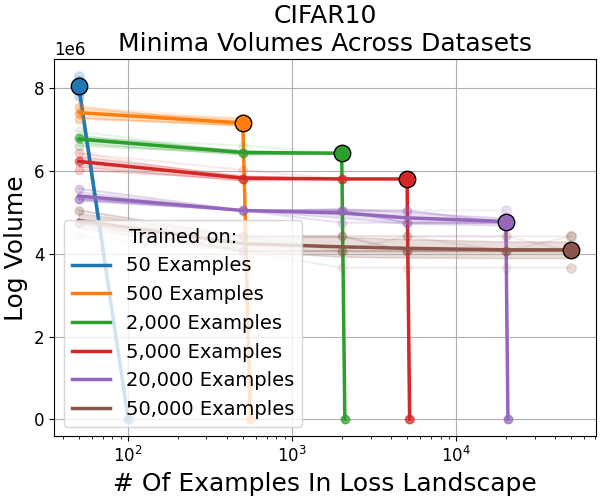

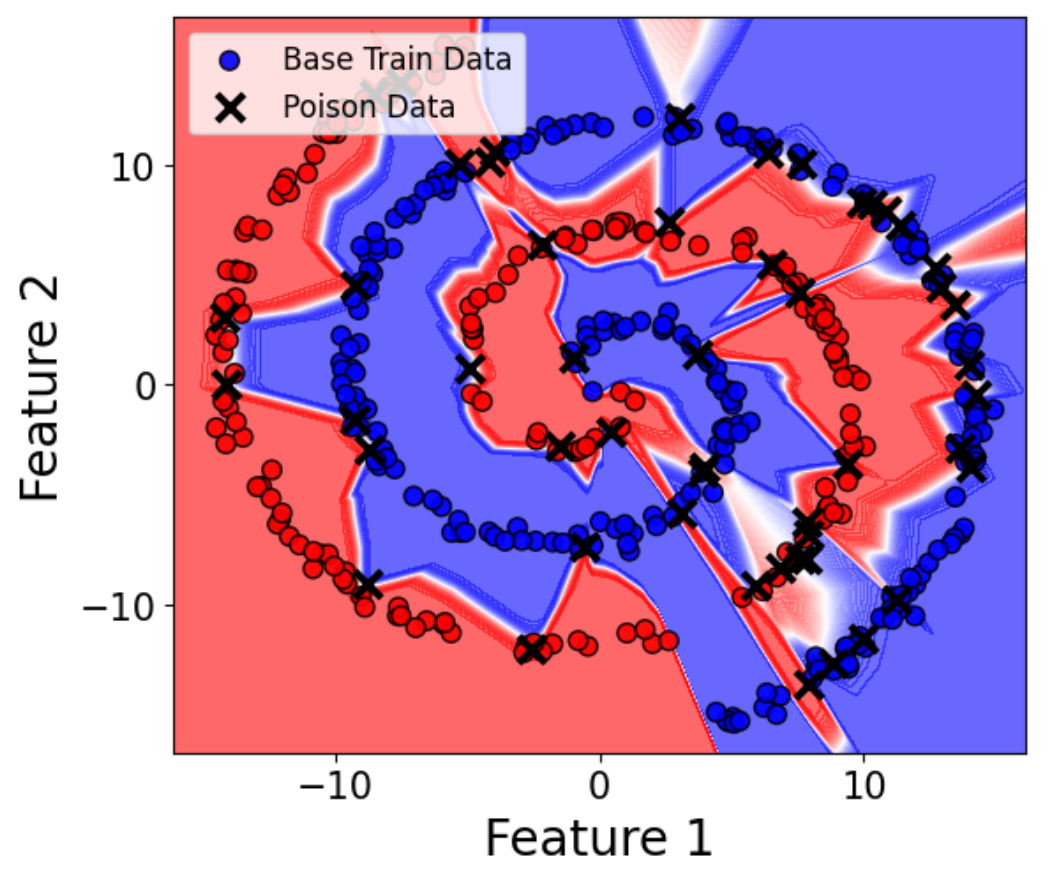

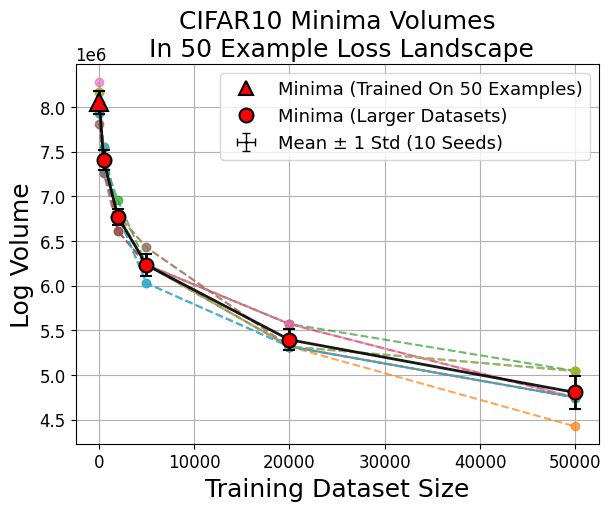

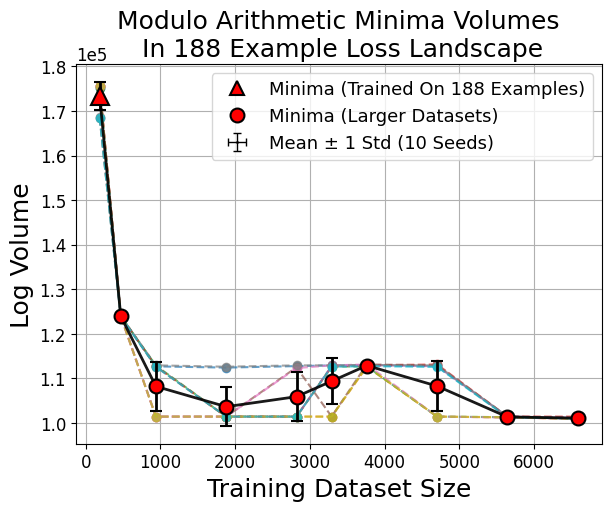

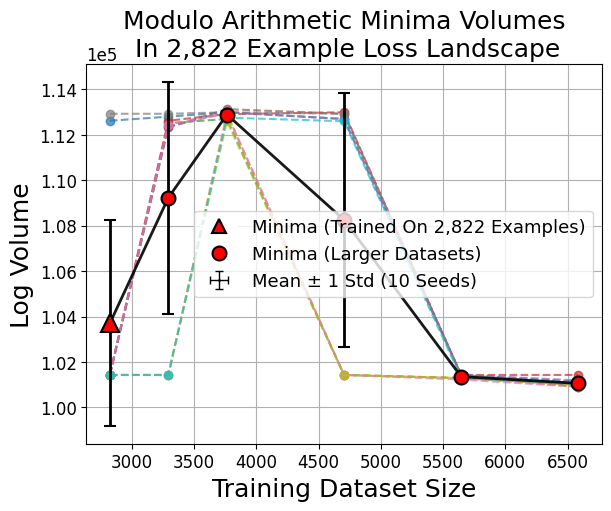

When smaller fractions of the dataset are used for training, the discovered minima are flatter (occupy larger volume in parameter space) but generalize less. Conversely, minima found using larger datasets are sharper (smaller volume), and yet generalize better; their volume in the loss landscape for small datasets remains tiny (Figure 5, Figure 6).

Figure 5: 2D MNIST loss landscape slices show only models trained on all data are viable minima for the full dataset; minima found in small subsets appear large only in limited landscapes.

Figure 6: Larger dataset-trained minima (red circles) evaluated in small-data loss landscapes consistently show smaller volumes compared to small-data minima (red triangle).

Strong numerical results indicate a consistent power-law shrinkage of minima volume with growing dataset size for MNIST, CIFAR10, SVHN, and Fashion MNIST:

log(V)=α⋅log(D)

with α<0 depending on model architecture (Figure 7, Table 1).

Figure 7: Across data scales, minima volumes show a power-law decay with increasing dataset size, and minima trained on a landscape are always the largest therein.

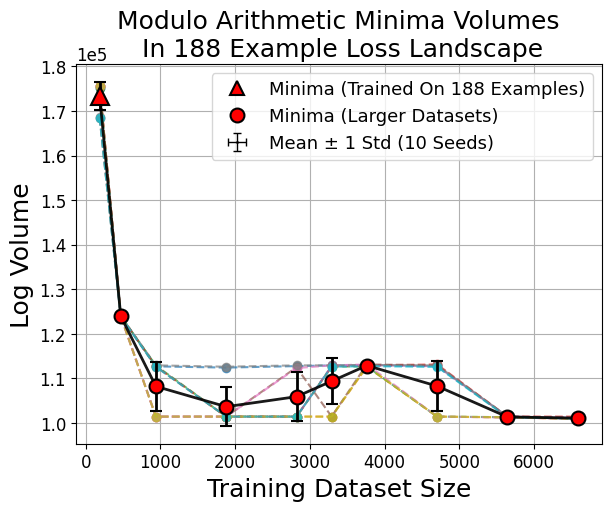

Outliers: Swiss Roll and Modulo Arithmetic

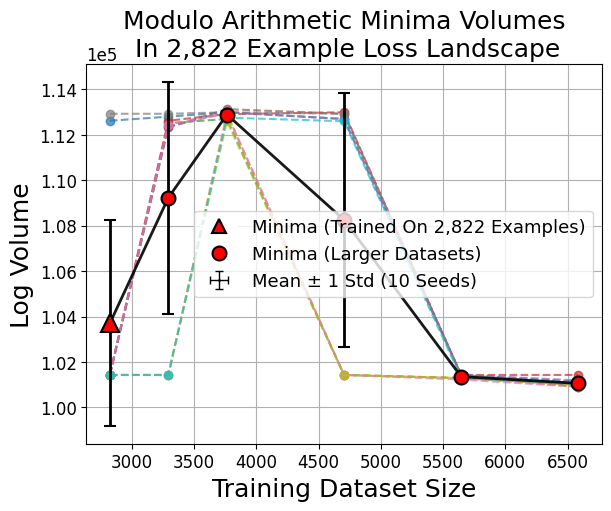

Unlike image classification, swiss roll classification and modulo arithmetic sometimes yield minima from larger datasets that are not the largest by volume. This reflects a transition where many small sharp minima collectively dominate the volume, consistent with the weak volume hypothesis (Figure 8).

Figure 8: In swiss roll and modulo arithmetic, the largest minima by volume need not be those found by training, indicating a high multiplicity of viable sharp minima.

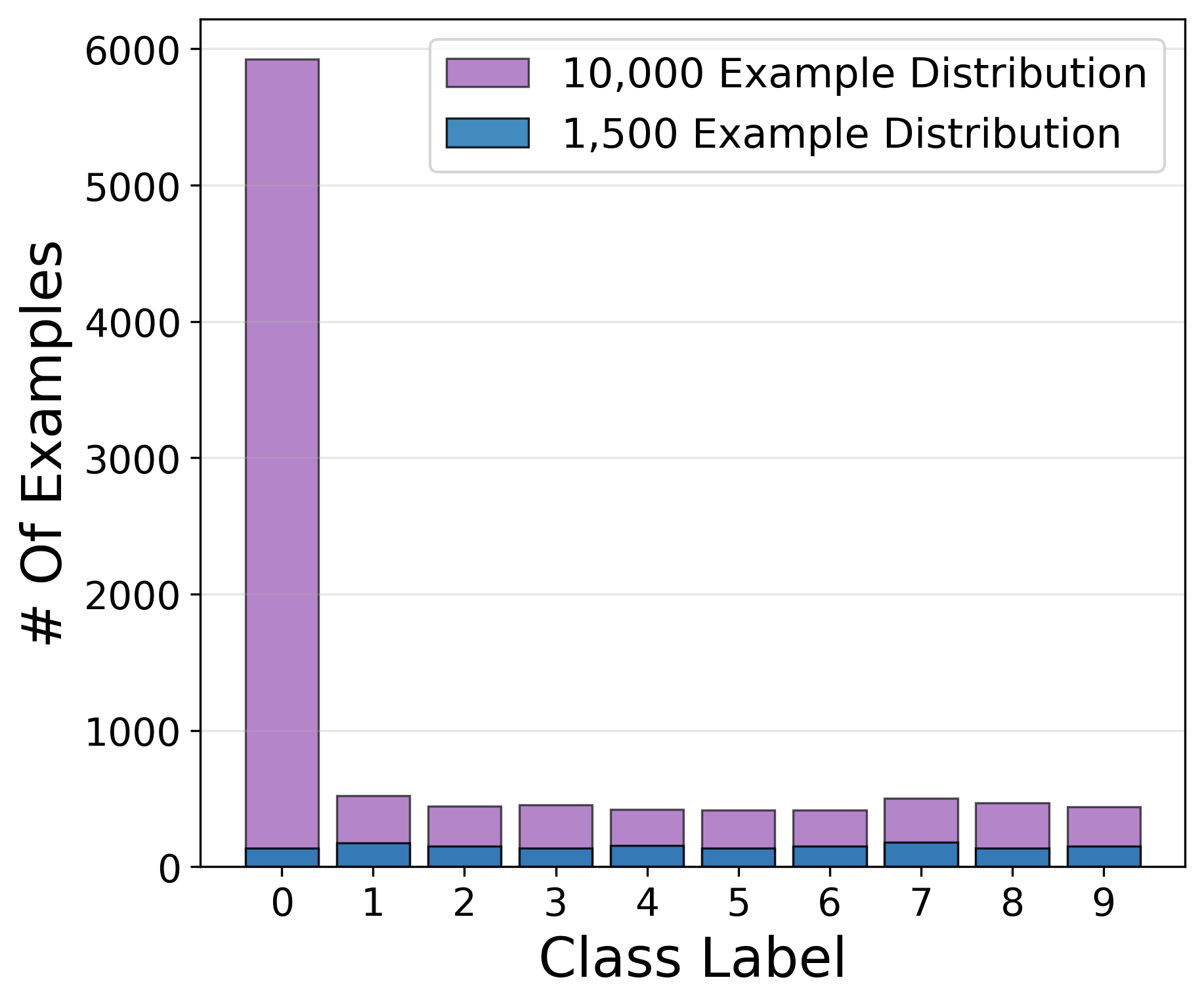

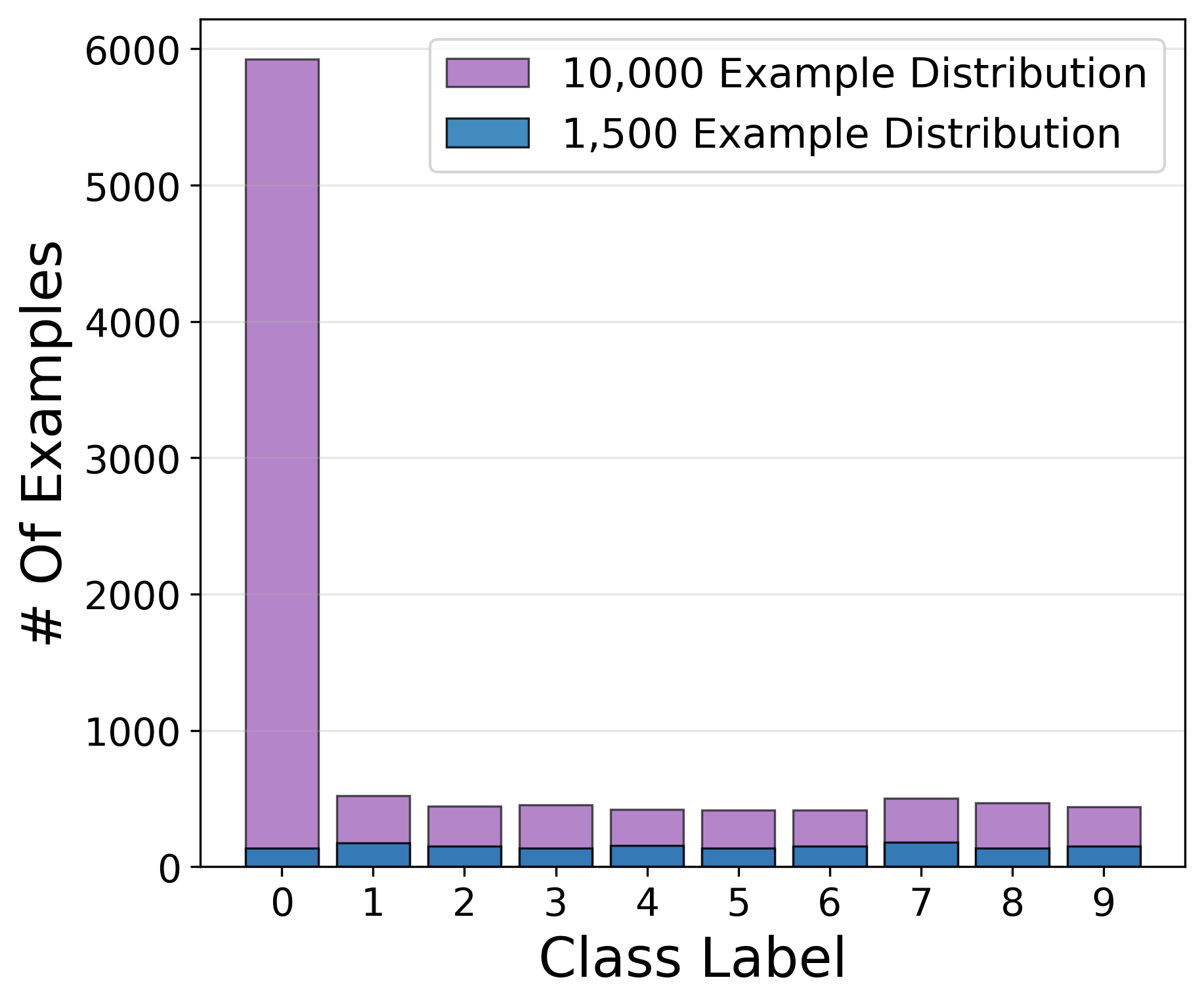

Class imbalance provides rare cases where minima volume increases with data, confirming that volume-dataset monotonicity is not strictly universal (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Class-imbalanced datasets can, contrivedly, produce minima whose basin volume grows with more data.

Counterexamples to Flatness: Perturbation Analysis

Histograms of perturbation radii (Figure 10) demonstrate that empirically, low-data minima are indeed flatter—even by alternative metrics—and reinforce the volume hypothesis as a predictor of their overfit behavior.

Figure 10: In low-data MNIST landscapes, random perturbations travel farther before crossing the loss threshold for small-data minima than for large-data minima.

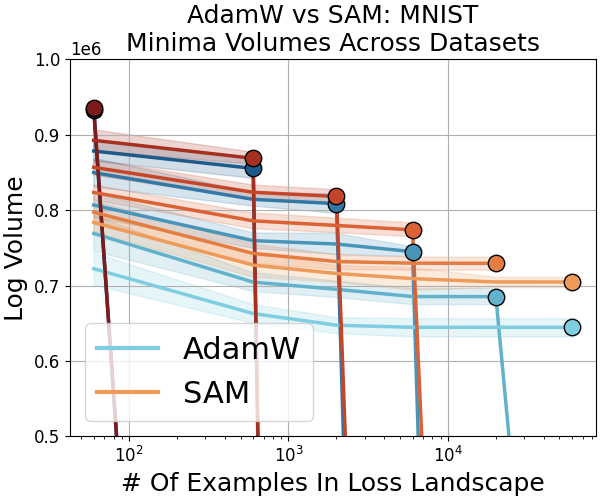

Optimization Variants: Sharpness-Aware Minimization

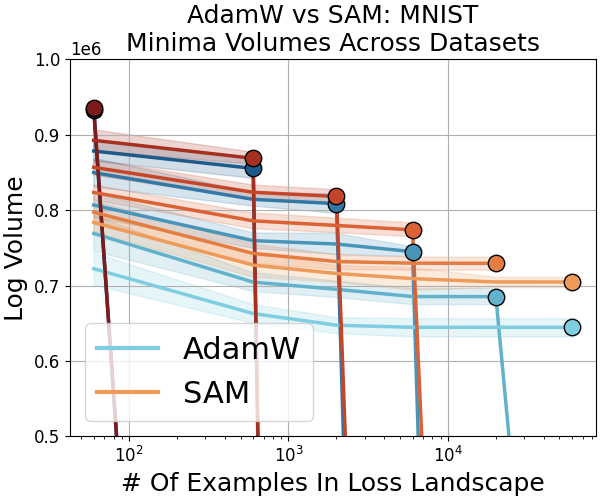

Sharpness-aware minimization (SAM) is shown to reliably find larger-volume minima and moderately improve test accuracy, especially in swiss roll tasks with scant data. However, the nature of generalization differs from that induced by larger datasets (Figure 11).

Figure 11: SAM improves basin volume and accuracy compared to AdamW, confirming but also refining the link between flatness and generalization.

Grokking Dynamics

During grokking—where models trained on algorithmic tasks (e.g., modular arithmetic) abruptly transition from memorization to generalization after extended training—volume continuously shrinks, with generalization occurring not at the flattest minima but in sharp ones of low complexity (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Grokking is marked by gradual basin volume decrease even as accuracy eventually spikes, indicating generalization cooccurs with sharp minima.

Implementation Guidance

Measuring Basin Volume

Empirical basin volume estimation is practical with the following approach:

- Train networks at various data fractions and collect final parameter states.

- From each minima, sample K random unit directions, apply filter normalization to ensure scale invariance.

- For each direction, compute the radius to the loss threshold via forward passes (typically K=500 directions).

- Estimate basin volume via averaging rn over all directions.

Batching evaluations and using robust normalization procedures improves numerical stability. Resolution and thresholds affect absolute volumes, but trends and relative comparisons remain stable (Figures 17–20).

Computational Constraints

- High parameter count leads to volumes spanning multiple OOM, but empirical volume comparison is reliable due to large separation—numerical noise does not confound key results.

- Variability due to random seeds and data splits is modest except in low-dimensional or high-minima-multiplicity tasks (swiss roll).

Implications for Generalization Theory

- Volume Hypothesis Supersedes Flatness: Empirical evidence shows that sharp minima resulting from large datasets are unlikely to be found in small dataset landscapes due to their small basin volume, but generalize well. Flat minima are readily found yet often overfit, especially in low-data regimes.

- Scaling Laws: Basin volume shows a robust power-law decay with dataset size for image classification architectures, hinting at underlying geometric or manifold constraints and possible links to neural scaling laws [kaplan_scaling_2020].

- Multiplicity and Inductive Biases: In cases with many viable sharp minima, collective volume rather than individual minima volume governs which solutions are discovered.

- Optimization and Generalization: Techniques prioritizing flatness (SAM, small batch sizes) reliably find larger-volume minima with better generalization in representative data landscapes, but do not outperform sharp minima found by training with larger datasets.

Future Directions

- Algorithmic Generalization: Future approaches in data-efficient learning may benefit from targeting sharp minima that generalize, though current optimizers rarely locate such solutions without sufficient data coverage.

- Volume-Based Search: Investigating specialized optimization techniques that explicitly search for minima with desirable volume-scaling properties could improve sample efficiency.

- Beyond Vision: Expansion of volume-dataset scaling analyses to sequences and structured prediction problems (e.g., language modeling) could uncover universal trends or domain-specific structures.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the geometry of loss landscapes—especially basin volume—plays a crucial role in neural network generalization, often outweighing local flatness measures. Large dataset training discovers sharp minima with superior generalization that are unreachable in small landscapes due to their negligible volume, directly refuting simplistic flatness hypotheses. Empirical power-laws in minima volume scaling and nuanced results in tasks with high minima multiplicity illustrate the need for a more sophisticated theory of generalization, one that accounts for both data-induced landscape transformation and implicit bias dynamics of modern optimizers.

Figure 5: Larger dataset training discovers sharp, generalizing minima that are invisible in low-data landscapes due to their small associated volume.

Figure 7: Basin volume scales with dataset size according to a power-law, confirming strong geometric effects in deep learning generalization.

Figure 12: The grokking phenomenon reveals how generalization can coincide with sharp minima in algorithmic tasks, challenging the universality of flatness-based explanations.