Physics-Informed Neural Networks and Neural Operators for Parametric PDEs: A Human-AI Collaborative Analysis (2511.04576v2)

Abstract: PDEs arise ubiquitously in science and engineering, where solutions depend on parameters (physical properties, boundary conditions, geometry). Traditional numerical methods require re-solving the PDE for each parameter, making parameter space exploration prohibitively expensive. Recent machine learning advances, particularly physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and neural operators, have revolutionized parametric PDE solving by learning solution operators that generalize across parameter spaces. We critically analyze two main paradigms: (1) PINNs, which embed physical laws as soft constraints and excel at inverse problems with sparse data, and (2) neural operators (e.g., DeepONet, Fourier Neural Operator), which learn mappings between infinite-dimensional function spaces and achieve unprecedented generalization. Through comparisons across fluid dynamics, solid mechanics, heat transfer, and electromagnetics, we show neural operators can achieve computational speedups of $103$ to $105$ times faster than traditional solvers for multi-query scenarios, while maintaining comparable accuracy. We provide practical guidance for method selection, discuss theoretical foundations (universal approximation, convergence), and identify critical open challenges: high-dimensional parameters, complex geometries, and out-of-distribution generalization. This work establishes a unified framework for understanding parametric PDE solvers via operator learning, offering a comprehensive, incrementally updated resource for this rapidly evolving field

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper looks at a big challenge in science and engineering: solving equations that describe how things change, like air flowing around a wing, heat moving through a metal, or stress inside a bridge. These equations are called partial differential equations (PDEs). In the real world, the answers to these equations depend on “settings” or “knobs,” such as material properties, shapes, and boundary conditions. Those settings are called parameters.

The main idea of the paper is to explain new AI methods that can solve these parameter-dependent PDEs much faster when you need answers for many different settings. It compares two families of methods:

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

- Neural Operators (like DeepONet and the Fourier Neural Operator, FNO)

It also shows how humans and AI worked together to write and verify this survey.

What questions did the authors ask?

To make the topic easier to understand, the authors focused on a few simple questions:

- How do PINNs and neural operators work, in plain terms?

- Which one should you use for which kind of problem?

- How much faster are these methods compared to traditional solvers?

- What do we know in theory about why they work (like guarantees and proofs)?

- What are the biggest open challenges (for example, lots of parameters, strange shapes, or surprising inputs)?

- How can a human-AI team safely write a survey without the AI “making things up”?

How did they do the paper?

This is a survey paper, which means the authors didn’t run one big new experiment. Instead, they:

- Collected and read many published research papers across physics and engineering (fluid dynamics, solid mechanics, heat transfer, electromagnetics).

- Compared methods and reported what others found (accuracy, speed, and when each method works best).

- Organized the ideas under a shared point of view called “operator learning,” which treats solving a PDE as learning a mapping from inputs (parameters or functions) to outputs (solutions).

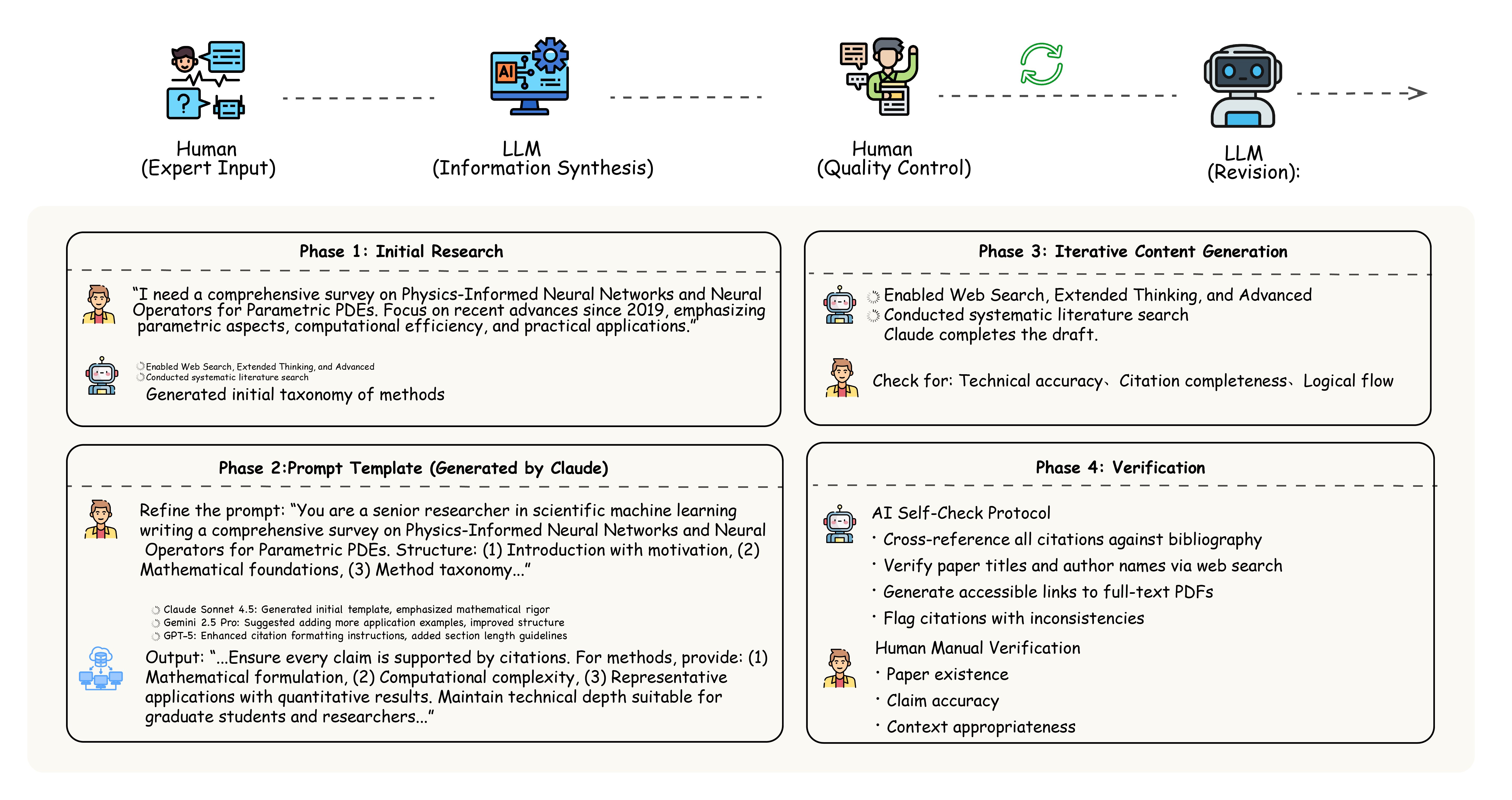

- Used a human-AI process: humans planned and checked; AI wrote drafts and formatted; humans verified references and corrected the content to reduce mistakes.

To explain key terms with everyday language:

- PDEs: equations that describe how things change over space and time (like how smoke spreads in the air).

- Parameters: the “settings” of the problem (like the wind speed, the shape of an object, or the temperature at the edges).

- Operator: think of it like a special machine that takes inputs (parameter values or functions) and instantly gives the full solution field as output.

- Neural operator: a learned version of that machine, built with a neural network, that can handle many inputs without retraining.

- PINN: a neural network that learns a solution by obeying the physics rules (the PDE) during training.

PINNs in simple terms

A PINN is like a student who learns by following the rules of physics. During training, the PINN checks whether its guess satisfies the equation and the boundary conditions. If not, it adjusts. PINNs are great when you don’t have much data but you know the physics. They can also find unknown parameters (like the viscosity of a fluid) from limited measurements.

However, PINNs often struggle to generalize across very wide ranges of parameter values. If you change the “knobs” too much, you may need to retrain or fine-tune.

Neural operators in simple terms

A neural operator tries to learn the “machine” that maps inputs to solutions. After training once, you can feed it many different parameter values or input functions, and it quickly outputs the solution—no retraining needed. That’s why neural operators are strong for “multi-query” tasks, where you need answers for many different settings.

Two popular examples:

- DeepONet: splits the work into a “branch” that reads the input function/parameters and a “trunk” that reads the location where you want the solution, then combines them.

- Fourier Neural Operator (FNO): works in the frequency domain (like breaking a signal into musical notes) to capture patterns efficiently across space.

A special bonus of neural operators is “discretization invariance”: you can train on coarse grids and still predict on fine grids later, like learning the overall shape of a melody and then playing it in high resolution.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

The key takeaways are:

- For many-query problems (needing solutions for lots of different parameter values), neural operators can be extremely fast—about 1,000 to 100,000 times faster than traditional solvers—while keeping similar accuracy. That makes tasks like design exploration and uncertainty quantification practical.

- PINNs are especially good when data is scarce and you have strong physics knowledge, or when you need to discover hidden parameters (inverse problems). They are flexible and don’t need meshes (grids), which helps with complex shapes.

- Traditional reduced-order methods (older, well-established techniques) work well when parameters are few and the solution behaves smoothly, but they struggle when parameter spaces are large, geometries change, or the behavior is nonlinear.

- The field has growing theory: universal approximation for operators, early convergence results, and improved training strategies. But better guarantees and stability are still active research areas.

- There are important open challenges: handling very high-dimensional parameter spaces, complex and changing geometries, generalizing to out-of-distribution cases (surprising inputs), and doing uncertainty quantification reliably.

In short: if you want one fast model that handles many parameter settings, neural operators are often the best choice. If you need to estimate hidden physical values from sparse data, PINNs shine.

What could this change in the real world?

These advances can make a big difference in places where speed and reliability matter:

- Real-time decision-making: medical simulations, robotics, and control systems can run in milliseconds instead of hours.

- Engineering design: exploring many designs (like different wing shapes) becomes affordable, accelerating innovation.

- Uncertainty quantification: testing thousands to millions of scenarios becomes possible, improving safety and confidence.

- Complex physics: easier coupling of multiple physical effects and handling changing shapes without remeshing.

- Scientific writing: careful human-AI collaboration can speed up the creation of technical surveys, as long as humans verify the facts.

Overall, the paper shows a path toward “learn once, use many times” solvers, which could reshape how scientists and engineers explore, design, and make decisions under uncertainty.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or left unexplored in the paper, stated concretely to guide future research.

- Standardized, cross-domain benchmarks: No unified, open benchmark suite for parametric PDEs spanning complex geometries, high-dimensional parameters (d > 50), multi-physics, and deliberate in- and out-of-distribution splits; define protocols, metrics, and datasets with ground truth and reproducible baselines.

- Speedup claims and cost accounting: Reported 103–105 speedups lack a consistent evaluation methodology; quantify offline training cost amortization vs query volume, hardware/precision settings, and energy/carbon footprint to enable fair comparisons with traditional solvers.

- PINN generalization limits: The paper acknowledges PINN retraining needs but does not delineate the parameter ranges where a single PINN remains valid; establish failure modes, extrapolation boundaries, and criteria for when retraining or model adaptation is required.

- Neural operator robustness to non-smooth regimes: Missing theory and empirical stress tests for bifurcations, shocks, discontinuities, and regime transitions (e.g., laminar → turbulent); derive error and stability guarantees under parameter-induced qualitative changes.

- Sample complexity scaling: Unclear scaling of required training samples with parameter dimension d and solution manifold curvature; provide explicit N(d, ε) bounds and conditions for learnability in DeepONet/FNO/GNO.

- Discretization invariance limits: The zero-shot super-resolution claim is not rigorously characterized; identify conditions under which discretization invariance holds, quantify aliasing/spectral leakage, and analyze boundary treatment when training coarse and inferring fine.

- Geometry-parameter encoding: Insufficient treatment of parameterized geometries; develop robust encodings (e.g., meshless, implicit surfaces, signed distance fields), boundary condition enforcement across shapes, and equivariance/invariance to geometric transformations.

- Out-of-distribution (OOD) handling: No systematic OOD evaluation or mitigation; create OOD detection, abstention, and adaptation mechanisms with calibrated uncertainty for parametric PDE surrogates.

- Long-time stability and conservation: Lack of analysis for error accumulation in time-dependent problems across parameters; enforce and certify conservation laws/invariants (mass, energy, divergence-free) over long rollouts.

- Training stability and convergence: Multi-loss balancing (PINNs, PI-DeepONet) and stiffness-induced instabilities remain ad hoc; design optimization schemes with convergence guarantees (multi-objective weighting, second-order methods, operator preconditioning) that scale to 3D/high-Re.

- Spectral bias control: Existing fixes are heuristic; develop architectures/training regimes with tunable frequency response to reliably capture boundary layers, shocks, and multiscale features that vary with parameters.

- Uncertainty quantification (UQ): Few calibrated, physics-consistent UQ frameworks for neural operators/PINNs; create Bayesian or conformal approaches with coverage guarantees, link uncertainty to PDE residuals, and define thresholds for safe deployment.

- Active learning over parameter space: Parameter-space sampling strategies lack theory and standards; formulate error estimators and greedy policies with provable guarantees analogous to reduced basis methods.

- Hybrid methods (ROM + ML): Limited guidance on when to combine reduced bases with operator learning or PINNs; systematically compare hybrid pipelines and design adaptive switching across parameter regimes.

- Data generation and multi-fidelity training: No guidelines for efficient training data synthesis; quantify benefits of multi-fidelity (coarse → fine), transfer learning, and domain randomization to reduce high-fidelity solves.

- Scalability to industrial-scale PDEs: Demonstrations are isolated; address memory/automatic differentiation bottlenecks, distributed training, and mixed-precision strategies to generalize to large 3D, high-DOF, high-Re problems.

- Theoretical foundations beyond universality: Missing convergence rates, generalization bounds under parameter distributions, stability under noise/perturbations, and operator learning guarantees for non-elliptic, nonlinear PDE classes.

- Certification and a posteriori error bounds: Absence of deployable residual-based certificates and error estimators per query μ; develop certified surrogates with computable error bars for safety-critical use.

- Interpretability and structure preservation: Limited methods to attribute predictions to parameter variations or enforce symmetries/equivariances (e.g., rotational, translational); design structure-preserving operator architectures.

- Reproducibility of recent advances: SPINN, KINN, SPIKANs, Legend-KINN and related methods lack standardized, open implementations and pretrained models; release code, seeds, and evaluation pipelines for comparative studies.

- Human–AI survey methodology validation: The collaborative workflow to mitigate hallucinations is described but not quantified; measure reference accuracy, coverage bias, update cadence, and versioning to establish reliability of AI-generated surveys.

Glossary

- A posteriori error bounds: Computable error estimates that bound the true error of reduced models after solving. "Strengths: Rigorous a posteriori error bounds, systematic parameter space coverage, and theoretical optimality guarantees under affine parameter dependence."

- Affine parameter dependence: A structure where the PDE operator decomposes into parameter-independent components scaled by parameter-dependent coefficients, enabling efficient offline-online computation. "they require affine parameter dependence, meaning PDE operators must decompose as with parameter-independent operators ."

- Automatic differentiation: A technique to compute exact derivatives via the chain rule during model training, enabling PDE residual evaluation. "The automatic differentiation capability of modern deep learning frameworks enables efficient computation of PDE residuals through repeated backpropagation."

- Bayesian PINNs (B-PINNs): Probabilistic physics-informed neural networks that quantify uncertainty in parameters and predictions. "Bayesian extensions like B-PINNs \citep{Yang2021} and related uncertainty quantification approaches \citep{Yang2020Bayesian, Psaros2023, Lakshminarayanan2017, Tripathy2018} naturally quantify parameter and prediction uncertainties without requiring multiple forward solves."

- Bifurcations: Qualitative changes in solution behavior as parameters vary, often causing non-smooth dependence. "For instance, solutions may exhibit bifurcations, phase transitions, or shock formations at critical parameter values, making smooth interpolation impossible."

- Boundary layer: A thin region near boundaries with steep gradients, common in high-Reynolds-number flows. "For parametric problems with high-frequency features (shocks, boundary layers) that vary with parameters, this bias necessitates very deep networks or specialized architectures."

- Branch–Trunk decomposition: The DeepONet architecture splitting input-function encoding (branch) from coordinate encoding (trunk). "Architecture: Branch-Trunk Decomposition"

- Burgers equation: A nonlinear PDE modeling viscous wave propagation and shock formation. "Example: The parameterized Burgers equation models nonlinear wave propagation with viscosity parameter :"

- Curse of dimensionality: Exponential growth in sampling or computational requirements as the number of parameters increases. "Traditional methods suffer from the curse of dimensionality, where sampling complexity grows exponentially with parameter dimension."

- DeepONet: A neural operator architecture using branch and trunk networks to learn mappings between function spaces. "DeepONet, introduced by Lu et al. \citep{Lu2021} in Nature Machine Intelligence, represents the first practical implementation of operator learning achieving widespread success."

- Discretization invariance: The property that an operator model can be evaluated on different grid resolutions without retraining. "A crucial advantage of neural operator formulations is discretization invariance: the operator operates on continuous functions, not discrete grid representations."

- Fourier Neural Operator (FNO): A neural operator that performs global convolution via Fourier transforms to learn solution operators efficiently. "neural operators (including DeepONet, Fourier Neural Operator, and their variants)"

- Galerkin projection: A method that projects PDEs onto a finite basis to obtain reduced dynamical systems. "where coefficients are determined by Galerkin projection of the governing PDE onto the reduced space."

- Greedy algorithm: An iterative selection strategy that chooses parameter samples maximizing current model error to build reduced bases. "The greedy algorithm iteratively identifies the parameter where the current reduced model has largest error:"

- Hypernetwork: A neural network that outputs the parameters of another network conditioned on inputs (e.g., parameters). "where is a hypernetwork that generates weights conditioned on ."

- Ill-conditioning: Numerical instability arising from poorly conditioned optimization or PDE systems, hindering convergence. "established a fundamental connection between PINN ill-conditioning and the Jacobian matrix condition number of the PDE system."

- Jacobian matrix condition number: A measure of sensitivity of solutions to perturbations, influencing training stability and convergence. "established a fundamental connection between PINN ill-conditioning and the Jacobian matrix condition number of the PDE system."

- Karhunen–Loève expansion: A representation of stochastic processes or snapshot data akin to PCA, used in reduced-order modeling. "Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD), also known as Principal Component Analysis or Karhunen-Loève expansion, forms the cornerstone of traditional ROM approaches"

- Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KAN): Neural architectures with learnable spline-based activations inspired by the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem. "Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN), which replace fixed activation functions with learnable spline-based functions."

- Legend-KINN: A KAN-based physics-informed model leveraging Legendre polynomials and pseudo-time stepping for fast convergence. "Most recently, \citet{Zhang2025LegendKINN} proposed Legend-KINN, integrating Legendre orthogonal polynomials into the KAN architecture combined with pseudo-time stepping in backpropagation."

- Multi-level Monte Carlo (MLMC): A variance reduction technique combining low- and high-fidelity simulations to reduce cost in UQ. "Multi-level Monte Carlo (MLMC) \citep{Giles2015} tackles high-dimensional uncertainty quantification by combining low-fidelity (coarse mesh) solutions with high-fidelity corrections, achieving variance reduction without prohibitive cost."

- NACA profile parameters: Coefficients defining standardized airfoil geometries used in aerodynamic modeling. "where represents coefficients in a geometric parameterization (e.g., NACA profile parameters or Bézier control points):"

- Navier–Stokes equations: Fundamental PDEs governing fluid motion, including conservation of momentum and mass. "must solve the governing Navier-Stokes equations independently for each parameter configuration."

- Neural operators: Models that learn mappings between infinite-dimensional function spaces, enabling parameter-space generalization. "neural operators (including DeepONet, Fourier Neural Operator, and their variants), which learn mappings between infinite-dimensional function spaces and achieve unprecedented parameter space generalization."

- Operator learning: The paradigm of learning solution operators (maps from inputs to solutions) directly, rather than individual solutions. "This work establishes a unified framework for understanding parametric PDE solvers through the lens of operator learning"

- Operator preconditioning: Reformulating the operator or training to improve conditioning and accelerate convergence. "De Ryck et al. \citep{DeRyck2024Operator} provided an operator preconditioning perspective on physics-informed training."

- Parametric PDE: A PDE whose coefficients, boundary/initial conditions, or domain depend on parameters. "A parametric PDE is defined as:"

- Péclet number: A dimensionless quantity comparing advective transport to diffusive transport in flows. "flow regime indicators (Reynolds, Rayleigh, Péclet numbers)"

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs): Neural networks trained with loss terms enforcing PDEs, boundary/initial conditions, and data. "physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), which embed governing equations as soft constraints and excel at inverse problems with sparse data"

- Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD): A method that extracts optimal low-dimensional modes from snapshots for reduced-order modeling. "The Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD), also known as Principal Component Analysis or Karhunen-Loève expansion, forms the cornerstone of traditional ROM approaches"

- Reduced basis methods: ROM techniques that build a basis via greedy sampling guided by error estimators across parameter space. "Reduced basis (RB) methods \citep{Quarteroni2015, Hesthaven2016, Rozza2008} extend POD through sophisticated greedy algorithms for parameter space exploration."

- Reduced order models (ROMs): Low-dimensional surrogate models of high-fidelity PDE simulations used to accelerate multi-query tasks. "Classical reduced order models (ROMs) have been developed over decades, establishing rigorous mathematical foundations that inform contemporary developments."

- Residual-Based Adaptive Refinement (RAR): A training strategy that concentrates samples in regions with high PDE residuals. "Residual-Based Adaptive Refinement (RAR): At each training iteration, compute residuals at all collocation points and preferentially sample from high-residual regions \citep{Daw2022, Gao2023, Lu2021Adaptive, Wu2020}:"

- Reynolds number: A dimensionless quantity indicating the ratio of inertial to viscous forces, governing flow regimes. "fluid dynamics demanding Reynolds number sweeps,"

- Smolyak's algorithm: A sparse grid construction method enabling efficient high-dimensional approximation. "sparse grid methods based on Smolyak's algorithm \citep{Bungartz2004} provide a middle ground between full tensor-product grids and random sampling."

- Sobolev space: A function space incorporating derivatives into its norm, commonly used for PDE solution analysis. "where is an appropriate function space (e.g., Sobolev space)."

- Spectral bias: The tendency of neural networks to learn low-frequency components before high-frequency ones. "Neural networks exhibit spectral bias toward learning low-frequency components of solutions \citep{Rahaman2019}."

- SPIKANs: Separable physics-informed KAN architectures applying separation of variables for efficiency. "Separable Physics-Informed Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (SPIKANs), applying the separation of variables principle to KANs."

- SPINN: Separable PINN architectures that operate per axis to reduce complexity and memory usage. "To mitigate the curse of dimensionality in multi-dimensional PDEs, \citet{Cho2023Separable} introduced Separable Physics-Informed Neural Networks (SPINN)."

- Solution operator: The mapping from parameters and inputs to the full PDE solution in function space. "From an operator perspective, we seek to approximate the parameter-to-solution map (or solution operator):"

- Universal approximation (operators): Theoretical guarantee that neural operators can approximate continuous operators arbitrarily well. "Chen and Chen \citep{Chen1995} established that neural networks can approximate continuous operators arbitrarily wellâa result generalized by Kovachki et al. \citep{Kovachki2021} for modern neural operator architectures."

- Uncertainty quantification (UQ): Estimating the impact of uncertainties in inputs and models on outputs. "Uncertainty quantification (UQ): Modern engineering design must account for uncertainties in material properties, manufacturing tolerances, and operational conditions."

- Zero-shot super-resolution: Evaluating learned operators on finer grids than training data without additional training. "This means a neural operator trained on coarse-resolution data can evaluate solutions on fine-resolution gridsâa capability called zero-shot super-resolution that has no traditional numerical methods analogue."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now using physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and neural operators, leveraging documented speedups (up to 103–105 for multi-query scenarios), inverse problem capabilities, and mesh-free formulations across fluid dynamics, solid mechanics, heat transfer, and electromagnetics.

- Aerospace and Automotive: rapid parametric CFD/FEA surrogate inference for design optimization

- Use case: integrate FNO/DeepONet-based Navier–Stokes surrogates into CAD/CFD workflows (e.g., OpenFOAM, ANSYS) to run large parameter sweeps (Reynolds number, angle of attack, airfoil shape) in seconds for design-of-experiments and optimization.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Operator-in-the-loop” CAD plugin; ONNX/TensorRT-deployed inference microservice; gradient-free optimizer coupled to operator model.

- Assumptions/dependencies: training coverage across target parameter ranges; validated error bounds vs. baseline solvers; offline training compute; mesh-to-geometry parameterization fidelity; no OOD shifts during use.

- Energy, Chemicals, and HVAC: real-time digital twins for process control

- Use case: embed neural operators of heat transfer and fluid mixing into plant controllers (ms-scale inference) to support setpoint optimization, fault detection, and soft sensing.

- Tools/products/workflows: physics-aware model predictive control (MPC) with operator inference; drift monitoring via uncertainty quantification; edge deployment.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stable operating regimes; sufficient sensor coverage; periodic recalibration to mitigate domain shift; governance over safety envelopes.

- Civil/Structural Health Monitoring: PINN-based parameter identification from sparse sensors

- Use case: infer elastic moduli, damping, or damage parameters from limited strain/displacement data; calibrate finite-element models for bridges or aircraft components.

- Tools/products/workflows: PINN inverse module treating parameters as learnable; Bayesian PINNs for uncertainty; integration with SCADA and digital twin dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: correct governing equations and boundary conditions; identifiable parameters; noise-aware loss design; sensor placement quality.

- Healthcare (Hemodynamics): patient-specific flow calibration with sparse measurements

- Use case: reconstruct velocity/pressure fields and estimate viscosity/Reynolds numbers from limited imaging (e.g., Doppler ultrasound or MRI) for pre-operative planning support.

- Tools/products/workflows: PINN inverse modeling with physics-informed loss; clinician-facing visualization; data assimilation with sparse measurements.

- Assumptions/dependencies: vetted biophysical models; measurement noise handling; clinical validation; regulatory compliance for decision support.

- Climate and Weather: accelerated ensemble forecasts and downscaling

- Use case: leverage neural operators for multi-member ensembles in UQ (104 samples feasible) and zero-shot super-resolution to produce higher-resolution fields from coarse simulations.

- Tools/products/workflows: surrogate-assisted 4D-Var or EnKF data assimilation; operator-based downscaling services; forecast post-processing pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: training distribution matches forecast regimes; multi-physics coupling approximations; bias correction; robust handling of extremes.

- RF and Antenna Design: rapid electromagnetics param sweeps

- Use case: operator surrogates map geometry and boundary conditions to field distributions and S-parameters; accelerate antenna and RF component optimization.

- Tools/products/workflows: DeepONet for geometry-conditioned EM response; CAD integration; multi-objective optimization loop.

- Assumptions/dependencies: accurate geometric encoding; high-quality FEM data for training; controlled parameter ranges to avoid OOD failure.

- Manufacturing and Materials: PDE-constrained data assimilation

- Use case: combine operator surrogates with data assimilation to update state estimates in casting/thermal processes; reduce scrap and stabilize quality.

- Tools/products/workflows: operator-in-the-loop 4D-Var-like update; uncertainty-aware quality control; edge inference.

- Assumptions/dependencies: validated heat transfer and phase-change models; sufficient telemetry; process stationarity within trained regimes.

- Design-of-Experiments and UQ: multi-query surrogate acceleration

- Use case: replace full solver calls with operator inference in Monte Carlo/UQ pipelines; propagate tolerances and material variability through PDE solutions.

- Tools/products/workflows: surrogate-enabled risk analysis; sensitivity studies; PSA (probabilistic safety assessment) dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: representative training set covering uncertainty; calibrated uncertainty estimates; governance over decision thresholds.

- Education and Academia: interactive parametric PDE labs and method selection guidance

- Use case: students run param sweeps for canonical PDEs (Burgers, Poisson, Navier–Stokes) in seconds; compare PINNs vs. neural operators; rely on standardized benchmarks (e.g., PINNacle).

- Tools/products/workflows: browser-based notebooks; curriculum using operator learning; reproducible benchmark suites.

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to open datasets; GPU resources; curated examples avoiding OOD pitfalls.

- Software and MLOps: CI/CD for scientific ML surrogates

- Use case: versioned training, validation, and deployment pipelines for neural operators; automated drift detection against embedded solver baselines.

- Tools/products/workflows: model registry; synthetic regression tests; continuous benchmarking; physics-aware monitoring metrics (PDE residuals, conservation violations).

- Assumptions/dependencies: well-defined test sets; domain governance; rollback strategies; reproducible training.

- Robotics and UAVs: lightweight dynamics emulation for planning

- Use case: deploy operator surrogates of simplified fluid-structure or contact models to speed motion planning and trajectory evaluation onboard.

- Tools/products/workflows: embedded inference via ONNX/TensorRT; hybrid model combining analytical dynamics with operator corrections.

- Assumptions/dependencies: targeted operating envelope; simplification of full PDEs; thorough validation under edge cases.

- PINN/Architecture Advances: industrial-grade PINN training workflows

- Use case: apply separable PINNs (SPINN) and KINN/Legend-KINN for complex geometries and multi-scale problems; exploit large collocation counts and faster convergence for single-query or few-shot scenarios.

- Tools/products/workflows: forward-mode AD pipelines; operator preconditioning; adaptive sampling and gradient alignment strategies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: problem amenable to separability or spline activations; stable training with multi-loss objectives; curated collocation strategies.

Long-Term Applications

The following applications require further research in generalization across high-dimensional parameter spaces, complex geometries, multi-physics coupling, out-of-distribution robustness, certification, and scalable training.

- Healthcare: personalized cardiovascular digital twins for surgical planning and closed-loop therapy

- Use case: patient-specific operators over anatomy and boundary conditions for real-time simulation during interventions; adaptive control of medical devices.

- Tools/products/workflows: operator training from population datasets; online personalization; regulatory-grade validation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: high-fidelity data access; robust OOD handling; clinical trials; FDA/EMA compliance.

- Aerospace: certified operator surrogates in safety-critical flight software

- Use case: onboard surrogates for aerodynamic loads and aeroelasticity; support real-time decision-making under changing conditions.

- Tools/products/workflows: formal verification/validation pipelines; uncertainty guarantees; fallback controllers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: rigorous theory (convergence, error bounds); certification standards; runtime monitoring to detect drift.

- Energy and Plasma: grid-scale real-time PDE controllers

- Use case: operator-based control of combustion, plasma confinement, or thermal networks; tighten stability margins and efficiency.

- Tools/products/workflows: hybrid physics–operator controllers; resilience to disturbances; hardware acceleration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust multi-physics coupling; extreme OOD resilience; safety and regulatory frameworks.

- Climate: kilometer-scale global ensembles with multi-physics operator foundations

- Use case: million-member ensembles, rapid UQ for climate policy; integrated Earth-system surrogates.

- Tools/products/workflows: foundation operator models spanning atmosphere, ocean, land, and ice; coupled data assimilation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: tractable training data at scale; trust and transparency; bias mitigation; long-horizon validation.

- Urban and Infrastructure Policy: city-scale digital twins for resilience planning

- Use case: coupled fluid–structure–traffic PDEs for scenario testing (floods, heat waves, pollution); inform building codes and emergency response.

- Tools/products/workflows: interoperable operator marketplace; privacy-preserving data fusion; policy dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: data integration agreements; fairness and equity considerations; transparent uncertainty communication.

- Autonomous Discovery: human–AI collaborative labs with operator learning

- Use case: AI agents curate literature, train operator surrogates, design experiments, and propose hypotheses; accelerate materials and fluid mechanics research.

- Tools/products/workflows: reference-checking workflows; experiment planning with UQ; continuous model updating.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable citation and dataset provenance; hallucination control; human oversight and governance.

- Cross-Domain Foundation Operators: generalizable models across PDE families

- Use case: pre-trained operators covering broad PDE classes and geometries; fine-tune for new tasks with minimal data.

- Tools/products/workflows: standardized benchmarks and data schemas; modular operator libraries; sector-specific adapters.

- Assumptions/dependencies: scalable training across diverse domains; transfer learning efficacy; licensing and IP frameworks.

- Robotics: high-fidelity onboard physics inference for manipulation and locomotion

- Use case: real-time contact, fluid interaction, and deformable-body surrogates integrated into planners for agile behaviors.

- Tools/products/workflows: multi-rate inference; uncertainty-aware planning; neuromorphic or ASIC accelerators.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stringent latency budgets; robust edge deployment; extensive validation under variability.

- Finance and Econometrics: PDE-based derivative pricing and risk UQ with operator surrogates

- Use case: accelerate param sweeps for stochastic PDEs (e.g., Black–Scholes variants) and stress testing with large ensembles.

- Tools/products/workflows: operator APIs in quant libraries; governance for model risk; audit trails.

- Assumptions/dependencies: faithful PDE formulations; regime changes and tail events; regulatory acceptance and explainability.

- Standards and Certification: V&V and benchmarking for scientific ML surrogates

- Use case: sector-wide protocols for error quantification, UQ, and OOD detection; shared datasets and challenge problems.

- Tools/products/workflows: PINNacle-like standardized testbeds; conservation-law checks; physics-residual metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: community consensus; regulatory alignment; sustained funding for open benchmarks.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.