Electromagnetic plasma wave modes propagating along light-cone coordinates (2511.04554v1)

Abstract: We present new electromagnetic plasma modes that propagates in one time and one space coordinates. Differently to the usual plane wave solution, which is written in terms of separation of variables, all our solutions are along the light-cone coordinates. This allow us to find several new wavepacket solutions whose functionality properties rely on the conditions imposed on the choice for their light-cone coordinates dependence. The presented wavepacket solutions are constructed in terms of multiplications of Airy functions, Parabolic cylinder functions, Mathieu functions, or Bessel functions. We thoroughly analyze the case of a double Airy solution, which have new electromagnetic properties, as a defined wavefront, and velocity faster than the electromagnetic plane wave counterpart solution. It is also mentioned how more general structured wavepackets can be constructed from these new solutions.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper explores new kinds of “plasma waves” (waves of electric and magnetic fields moving through a charged gas called plasma) that travel in a special way: along directions called light‑cone coordinates. Instead of using the usual plane waves that spread out evenly, the authors build wavepackets—compact lumps of waves—with unique shapes and behaviors, including sharp wavefronts and speeds that can get very close to the speed of light without breaking physics rules.

Goals in simple terms

The authors asked:

- Can we find exact (not approximate) wave shapes in a plasma that move mainly along paths that light would take?

- How do these new waves differ from ordinary plane waves in speed, shape, and energy flow?

- Can we design waves with special, useful structures (like strong, focused fronts) using known mathematical “building blocks”?

How they approached the problem

Think of waves as ripples that you can describe using coordinates (like “left–right” and “forward–back”). The authors used special coordinates that align with how light moves: one coordinate combines space and time as x−t, and the other as x+t. These are called light‑cone coordinates, and they basically follow the diagonal lines you’d draw for something moving at light speed.

Here’s the everyday idea:

- Usual method: Plane waves are like straight, evenly spaced ripples—easy to describe but not very flexible.

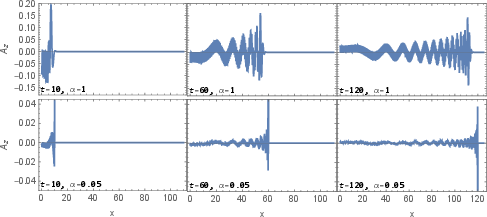

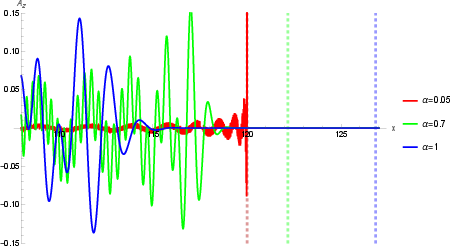

- Their method: Sculpt the wave using special “shapes” (mathematical functions) so it travels mostly along those light‑aligned directions. They pick two shapes and multiply them to build a wavepacket. The overall shape depends on a knob they can turn, called α (alpha), which decides how much the wave tracks each light‑cone direction.

To do this, they start with the basic wave equation for electromagnetic fields in a plasma (from Maxwell’s equations and simple plasma physics). Then they re-write it using light‑cone coordinates and choose special functions—like Airy functions, parabolic cylinder functions, Mathieu functions, and Bessel functions—to make exact solutions. These functions act like standard patterns or molds engineers might use.

Main results

Before listing the key findings, note that the authors found several families of exact wavepacket solutions by combining different special functions. Each family has a parameter α that controls how the wave leans toward one light‑cone direction.

Key discoveries:

- New wavepacket shapes: They built one‑dimensional (in space) wavepackets with rich, complex structures—very different from flat plane waves. These include “Double Airy,” “Double Parabolic Cylinder,” “Double Mathieu,” “Double Modified Mathieu,” and “Double Modified Bessel” modes. Each is made by multiplying two copies of a special function, tuned to track the light‑cone directions.

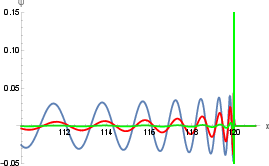

- Strong wavefronts: Especially in the “Double Airy” case, the wave develops a sharp, well-defined front that looks like a moving shock. As you turn down α (make it small), the wavefront becomes more localized and moves closer to the speed of light.

- Energy speed stays below light speed: The speed at which energy actually moves through the plasma (the energy velocity) is always less than the speed of light. This is important: even if certain parts of the wavefront look fast (or “superluminal,” like phase speeds), the energy obeys the speed limit of the universe.

- Accelerating waves: These wavepackets don’t travel at a constant speed; their speed changes as they move. This “accelerating” behavior is built in.

- Tailor‑made wavepackets: By mixing (averaging) many solutions with different α values, you can build a customized wavepacket that strengthens the shock‑like front and concentrates energy where you want it.

Why this matters:

- Practical control: These new structures give researchers tools to design how wave energy moves through plasmas—important for laser–plasma experiments and possibly for guiding energy precisely.

- Exact solutions: They are exact solutions of the full Maxwell equations (not approximations). That means they should be valid across a wide range of energies and conditions.

Implications and potential impact

These wavepackets could help scientists:

- Shape and steer electromagnetic energy in plasmas more precisely, which may improve experiments involving high‑intensity lasers and plasma interactions.

- Create focused fronts (like controlled shock‑like edges) that could be useful for particle acceleration or for delivering energy to specific places.

- Explore new kinds of “structured light” in plasmas, beyond what’s already done with beams like Airy‑Bessel or Laguerre‑Gaussian beams.

The authors also suggest these ideas can be extended to 3D wavepackets, opening the door to even richer structures and potentially more experimental applications.

Helpful mini‑glossary

To make the ideas clearer, here are brief explanations of key terms:

- Plasma: A gas where many particles are electrically charged (like in neon signs or the Sun).

- Light‑cone coordinates (x−t and x+t): Special combinations of space (x) and time (t) that track paths moving at light speed; imagine diagonal lines on a space–time grid.

- Wavepacket: A compact lump of wave energy, not an endless ripple; it can have a front and tail.

- Airy function: A smooth, wavy shape used in math and physics; known to create “self‑accelerating” beams in optics.

- Plane wave: A simple wave with evenly spaced crests, going on forever, often used as a basic model.

- Energy velocity: The speed at which energy travels in a wave; this must stay below light speed.

- Wavefront: The leading edge of a wavepacket where the change is strongest (like the front edge of a ripple).

- Exact solution: A solution that perfectly satisfies the equations, not an approximation.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following list identifies concrete gaps and unresolved questions left by the paper; each item highlights what is missing, uncertain, or unexplored and is framed to enable actionable follow-up by future researchers.

- Physical model scope:

- The analysis assumes a cold, relativistic, single-species plasma with constant density and no collisions; it leaves open how these wavepacket solutions change under finite temperature (thermal dispersion), collisional damping, Landau damping, and relativistic mass variations.

- The plasma is unmagnetized; it is unclear whether and how these light-cone wavepackets generalize in the presence of external magnetic fields, anisotropy, or cyclotron resonances.

- The “constant density” assumption suppresses self-consistent density perturbations; the paper does not examine whether the field structures drive density modulations that invalidate the linear wave equation used.

- Completeness and classification of solutions:

- The method “engineers” solutions by choosing θ(η), φ(ξ) so that Eq. (4) splits; there is no classification or proof of completeness for all admissible θ, φ that yield analytically tractable modes.

- A systematic procedure to generate and catalog broader families of solutions (beyond Airy, parabolic cylinder, Mathieu, modified Mathieu, and modified Bessel) is not provided.

- Orthogonality, completeness, and expansion properties of these modes (as a basis for general initial-value problems) are not analyzed.

- Domain and parameter constraints:

- The paper does not delineate the domains in (t, x) or parameter ranges (e.g., α, a, b) required for real-valued, nonsingular solutions (e.g., constraints like |αη| ≤ 1 for

cosθ = αη, positivity of arguments under square roots and inarccosh, branch selection forarccos/arccosh). - Conditions under which different special-function solutions become complex-valued, develop singularities, or require analytic continuation are not discussed.

- Sensitivity of the solution morphology and velocities to parameter choices (α, a, b, n) is not quantified.

- The paper does not delineate the domains in (t, x) or parameter ranges (e.g., α, a, b) required for real-valued, nonsingular solutions (e.g., constraints like |αη| ≤ 1 for

- Normalization, energy content, and tail behavior:

- Whether these wavepackets have finite total energy (integrated energy density over space) is not established; Airy, Bessel, and Mathieu-type functions often possess non-decaying or slowly decaying tails that can imply infinite energy.

- The paper qualitatively references “shock fronts,” but does not assess whether steepening is consistent with linear dynamics or quantify front thickness and tail contributions to energy flux.

- For the α-averaged superposition

𝔄(t,x,ω_p) = ∫ ζ(α) A^z(α) dα, the normalizability and energy convergence of the integral are not verified for various ζ(α).

- Velocities, causality, and signaling:

- The “wavefront velocity” defined via maxima of

∂_x A_z = 0is superluminal; the paper does not clarify how this relates to signal velocity and whether causality is preserved (e.g., does the earliest nonzero field propagate subluminally?). - The energy velocity

v_ε = |S|/εis shown to be subluminal, but the relationship between energy velocity, group velocity, and information (front) velocity is not rigorously established for these non-plane-wave solutions. - No explicit analysis is given of whether the superluminal wavefront is an artifact of the definition (akin to superluminal phase velocity) or could enable superluminal signaling.

- The “wavefront velocity” defined via maxima of

- Initial/boundary value realization:

- There is no prescription for initial conditions (Az and ∂_t Az at t=0) that would evolve into the proposed light-cone-structured solutions; practical excitation schemes (laser pulse shaping, boundary driving) are not detailed.

- Boundary conditions (finite-length plasmas, interfaces, waveguides) and their impact on solution persistence, reflections, and mode selection are not addressed.

- Stability of these solutions under realistic noise, boundary perturbations, and inhomogeneities is not analyzed.

- Experimental feasibility and diagnostics:

- Specific experimental parameters (plasma density ranges, pulse durations and intensities, diagnostics to detect and characterize the light-cone wavepackets) are not proposed.

- The paper does not outline methods for measuring energy velocity fields v_ε(t, x) or tracking the purported “shock-like” fronts in laboratory plasmas.

- 3D generalization:

- The suggested 3D extension using

A^z(t,x,y,z) = a^z(t,x) J_0(λ√(y^2+z^2))has not been analyzed for energy convergence (J0 does not decay) or for radial boundary conditions; how to construct localized 3D packets via distributions over λ remains unexplored. - The Lorenz gauge and full Maxwell consistency for the 3D construction (with nontrivial radial structure) are not demonstrated.

- The suggested 3D extension using

- Consistency with full Maxwell–fluid system:

- While setting

A^μ = -(m/q) U^μsimplifies the dynamics, the paper does not verify that the proposed Az solutions maintain the continuity equation and momentum equation self-consistently when fields accelerate charges (especially for large amplitudes). - Possible back-reaction (modification of ω_p via density changes or relativistic effects) is neglected; criteria for the validity of the linear, constant-ω_p approximation are not stated.

- While setting

- Mathematical rigor and reproducibility:

- Key formulas (e.g., wavefront position and velocity, energy velocity approximations) include typographical issues and missing parentheses, which hinder exact replication; a cleaned, verified set of expressions with domain conditions is needed.

- No numerical validation (e.g., direct integration of the wave equation with the proposed initial conditions) is presented to corroborate analytic predictions or figures.

- Polarization and multi-component fields:

- The analysis focuses on a single transverse component

A^z(t,x); coupling or coexistence of multiple polarizations/components (A^y,A^0,A^x) and their impact on wavepacket structure is not explored. - The Lorenz gauge constraint

∂_μ A^μ = 0is claimed satisfied “by construction,” but explicit verification for general light-cone-structured solutions (and for 3D extensions) is absent.

- The analysis focuses on a single transverse component

- Interaction with inhomogeneous or time-varying plasmas:

- How spatial gradients in density (or time-dependent ω_p(t)) affect the construction, propagation, and stability of the proposed modes is not studied.

- The possibility of adiabatic deformation or mode conversion of these wavepackets in graded-index plasmas is an open question.

- Nonlinear extensions:

- The paper’s solutions are strictly linear; the existence and behavior of analogous light-cone-structured wavepackets in weakly or strongly nonlinear regimes (e.g., relativistic self-phase modulation, ponderomotive effects) are not investigated.

- Mode diagnostics and invariants:

- Field invariants (e.g., E2 − B2, E·B), momentum density, and stress tensor distributions for the proposed wavepackets are not computed; these could clarify the physical character (e.g., radiation-like vs. quasi-electrostatic regions) of the solutions.

- Comparative performance:

- Quantitative comparison of energy velocity, localization, and robustness between the different special-function modes (Airy, parabolic cylinder, Mathieu, modified Bessel) is missing; criteria for choosing an optimal mode for applications are not provided.

- Practical synthesis of α-averaged packets:

- The paper uses

ζ(α) = exp(−δ α^2)illustratively, but does not provide a methodology to design ζ(α) for targeted wavefront speed profiles, localization, or energy transport characteristics, nor discuss constraints ensuring finite energy.

- The paper uses

These points suggest targeted theoretical, numerical, and experimental work to assess physical validity, stability, energy properties, and realizability of the proposed light-cone wavepacket modes in realistic plasma environments.

Glossary

- Airy-Bessel beams: Hybrid structured light modes combining Airy and Bessel profiles, often used in laser–plasma studies. "such as Airy-Bessel beams \cite{chong,Ren,Ersoy,Porat,Pawar}"

- Airy function: Special function (Ai, Bi) solving y'' − x y = 0, frequently appearing in diffraction and accelerating beam solutions. "multiplications of Airy functions, Parabolic cylinder functions, Mathieu functions, or Bessel functions."

- Bessel-Bessel beams: Structured beams formed by products of Bessel functions, yielding non-diffracting propagation characteristics. "or Bessel-Bessel beams \cite{salamin,salamin2,Kotlyar}"

- Bessel function: Special functions solving Bessel’s differential equation, fundamental in wave and cylindrical symmetry problems. "Bessel functions"

- Bessel-Gaussian beams: Beams with a Bessel transverse profile modulated by a Gaussian envelope, used for controlled propagation. "Bessel-Gaussian beams \cite{kant,Fallah,Hafizi,Hafizi2, Kulya}"

- Cold relativistic plasma: Plasma with negligible thermal motion but relativistic bulk flow, modeled via relativistic fluid equations. "a cold relativistic plasma with a single dynamic species"

- Continuity equation: Conservation law for particle number/current in a fluid or plasma, expressed covariantly. "the continuity equation "

- Covariant derivative: Derivative operator consistent with spacetime tensor calculus; here as a partial covariant derivative. "where is the partial covariant derivative"

- Dispersion relation: Relation between wave frequency and wavenumber that determines phase and group velocities in a medium. "with the dispersion relation for electromagnetic waves "

- Double Airy solution: A wave solution constructed as a product of two Airy functions with asymmetric dependence on light-cone variables. "We thoroughly analyze the case of a double Airy solution"

- Double Mathieu mode: A separable solution where both factors satisfy the Mathieu equation, yielding complex periodic structures. "Double Mathieu mode"

- Double Modified Bessel mode: A solution constructed using modified Bessel functions, tailored via exponential coordinate mappings. "Double Modified Bessel mode"

- Double Modified Mathieu mode: A separable solution where both factors satisfy the modified Mathieu equation involving hyperbolic cosine. "Double Modified Mathieu mode"

- Double Parabolic Cylinder mode: A solution using parabolic cylinder (Weber) functions with tunable parameters for asymmetry. "Double Parabolic Cylinder mode"

- Eikonal limit: High-frequency approximation where waves are treated as rays; often used to describe structured accelerating light. "not approximated solutions in the eikonal limit (as most of the structured accelerating light solutions are)."

- Energy velocity: The velocity of energy transport defined as the ratio of Poynting flux to energy density. "This energy velocity is defined as "

- Faraday tensor: The electromagnetic field-strength tensor F{μν} encoding electric and magnetic fields in relativistic form. "where is the Faraday tensor with as the electromagnetic four-potential."

- Four-potential: Relativistic potential A{μ} whose derivatives generate the electromagnetic field tensor. "where is the Faraday tensor with as the electromagnetic four-potential."

- Four-velocity: Relativistic velocity vector U{μ} of a fluid or plasma element. "four-velocity "

- Group velocity: Velocity of the wavepacket envelope, given by the derivative of the dispersion relation with respect to wavenumber. "Its group velocity, "

- Laguerre-Gaussian beams: Structured optical modes carrying orbital angular momentum, characterized by radial and azimuthal indices. "Laguerre-Gaussian beams \cite{Wang,culfa,Baumann,kad,patil}, among others."

- Light-cone coordinates: Null coordinates η = x − t and ξ = x + t used to analyze propagation along the light cone. "all our solutions are along the light-cone coordinates."

- Lorenz gauge: Gauge condition ∂_μ A{μ} = 0 used to simplify Maxwell’s equations. "the continuity equation reduces to the Lorenz gauge "

- Mathieu equation: Differential equation M''(y) + (a − b cos(y)) M(y) = 0 describing parametric resonance and periodic potentials. "Mathieu equation "

- Maxwell equations: Fundamental equations of electromagnetism governing E and B fields and their sources. "and the Maxwell equations"

- Modified Bessel function: Solutions (I_ν, K_ν) of the modified Bessel equation; K_0 commonly arises in radially varying problems. "where is the modified Bessel function of order 0."

- Modified Mathieu equation: Variant with hyperbolic cosine describing spatially varying parametric systems. "modified Mathieu equation, "

- Parabolic cylinder function: Special function D_p(y) solving the Weber equation; used to construct complex wave solutions. "the parabolic cylinder function"

- Phase velocity: Speed of constant phase surfaces (ω/k) that can exceed c in dispersive media without carrying information. "in the same sense that the phase velocity for simple plasma plane wave solution is superluminal."

- Plasma frequency: Natural oscillation frequency of charge carriers in a plasma, ω_p = √(q² n / m). "where is the (constant) plasma frequency"

- Poynting vector: Electromagnetic energy flux density S = E × B. "where is the Poynting vector"

- Shock front: Sharp leading edge of a wave where field amplitude changes abruptly, resembling a shock. "the waveform develop a shock front."

- Transverse electromagnetic polarization: Polarization with fields perpendicular to the propagation direction. "For transverse electromagnetic polarization (propagation along , the electromagnetic fields in the - plane)"

- Weber equation: Differential equation W''(y) = (a y² + b y − n) W(y) whose solutions are parabolic cylinder functions. "generalized Weber equation "

- Wavefront: The leading surface of a propagating wave, whose position and velocity can be defined and analyzed. "a well defined wavefront is one of its key features."

- Wavepacket: Localized superposition of waves with structured spatiotemporal evolution. "The presented wavepacket solutions are constructed in terms of multiplications of Airy functions, Parabolic cylinder functions, Mathieu functions, or Bessel functions."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed with existing tools and experimental capabilities, leveraging the paper’s exact 1D light-cone–based plasma wavepacket solutions (Airy, parabolic cylinder, Mathieu, modified Mathieu, modified Bessel) and their controllable wavefronts and energy transport.

- Plasma simulation benchmarking and code validation (academia, software)

- Use the exact solutions (e.g., double Airy, double Mathieu) as analytic test cases and initial/boundary conditions in Particle-in-Cell (PIC) and Maxwell solvers (e.g., WarpX, OSIRIS, EPOCH).

- Workflow: Implement Az(t,x; α) generators; check solver stability, dispersion, and energy velocity against closed-form predictions; conduct regression tests under grid refinement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cold, uniform-density plasma; single dynamic species; 1D or quasi-1D propagation; linear regime; no collisions/inhomegeneities.

- Laboratory proof-of-concept of light-cone wavepackets in underdense gas plasmas (photonics, laser–plasma)

- Generate approximate double Airy wavepackets by combined spatial (SLM) and temporal (4f pulse shaper, AOM) modulation to encode dependence on x±t; use gas cells or gas jets to create uniform underdense plasmas.

- Diagnostics: Shadowgraphy, interferometry, Thomson scattering, streak camera for wavefront tracking and energy transport.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Moderate intensities (linear or weakly nonlinear regime), uniform plasma density, careful calibration of spatio-temporal coupling to approximate light-cone functional forms; ignoring collisions/magnetic fields.

- Plasma density diagnostics using shock-like wavefronts (academia, instrumentation)

- Fit measured wavefront position vs time to the paper’s closed-form wavefront relation (parameters include α and ω_p) to infer electron density n via ω_p=√(q2 n/m).

- Workflow: Generate wavepacket, record xWF(t) with time-resolved imaging, perform parameter estimation for ω_p and α (with uncertainty quantification).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Validity of 1D and uniform-density approximations in the measurement region; accurate time-space calibration; known α or measured from the waveform.

- Spatio-temporal waveform design software for light-cone modes (software, photonics)

- Develop a “Light-cone Wavepacket Synthesizer” that outputs amplitude/phase masks (SLM/pulse shaper) to approximate the special-function envelopes along η=x−t and ξ=x+t, including α-superpositions for shock enhancement.

- Tools/products: Python/MATLAB toolboxes, mask-generation pipelines, integration with common lab hardware APIs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of high-resolution SLMs and programmable pulse shapers; bandwidth and phase stability sufficient to realize space–time coupled designs.

- 3D quasi-1D experiments via radial Bessel shaping (photonics)

- Implement the paper’s suggested 3D extension using Az(t,x,y,z)=az(t,x)J0(λ√(y2+z2)), achieved with axicons to produce Bessel beams, turning 1D light-cone solutions into cylindrically symmetric wavepackets with an effective plasma frequency √(ω_p2+λ2).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Radial symmetry maintained; control over λ distribution; uniform plasma columns or capillary waveguides; linear regime.

- Educational modules and visualization (education)

- Create interactive notebooks and teaching labs on light-cone coordinates, special-function wavepackets, and energy velocity behavior; include a library to compute Az(t,x;α) and visualize wavefront motion versus standard plane waves.

- Assumptions/dependencies: None beyond standard computing and plotting tools; idealized theoretical context.

Long-Term Applications

These directions require further research, scaling, or development to handle realistic plasma conditions (nonlinearity, inhomogeneity, collisions, magnetization), higher dimensionality, and integration with complex systems.

- Laser wakefield acceleration (LWFA) driver optimization (high-energy physics)

- Shape driver pulses to achieve near-c energy velocity largely independent of ω_p, potentially improving dephasing length and energy gain; investigate α-distributions that produce stable, accelerating wavefronts in underdense plasmas.

- Tools/workflows: Advanced spatio-temporal pulse shaping, PIC optimization studies, feedback control, experimental validation in gas jets/capillaries.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Extension to nonlinear regimes (relativistic intensities), self-focusing and plasma response, multi-D effects, compatibility with existing LWFA architectures.

- Inertial confinement fusion (ICF) energy deposition control (energy)

- Use shock-front–like wavepackets to tailor ablation fronts and improve implosion symmetry, exploiting well-defined wavefronts for precise timing and spatial energy delivery.

- Tools/workflows: Multi-beam shaping, α-averaged designs, integration with hohlraum/target geometries, 3D generalizations beyond J0 symmetry.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-power laser compatibility, target-plasma coupling, collisional/radiative effects, full 3D modeling and control.

- Ionospheric and plasma-channel communications with structured pulses (telecommunications)

- Explore wavepacket designs with near-c energy velocity to mitigate plasma-induced dispersion and group velocity reduction in ionospheric links or engineered plasma channels.

- Tools/workflows: RF/optical waveform shaping, channel modeling, field trials, adaptive modulation schemes informed by light-cone designs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Magnetized, collisional plasma modeling; regulatory constraints; scalability from optical to RF domains; environmental variability.

- THz/microwave propagation in plasma waveguides using Mathieu/Bessel modes (RF, defense)

- Engineer plasma channels or waveguides that support tailored modes (e.g., double Mathieu or modified Bessel) to reduce attenuation or control energy deposition profiles.

- Tools/workflows: Plasma channel generators, mode-matching structures, diagnostics; optimization of parameters (a, b, λ) for stability and performance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sustained, controllable plasma channels; compatibility with device-level requirements; full electromagnetic–plasma coupling.

- Atmospheric remote sensing and LIDAR with wavefront markers (environmental monitoring)

- Deploy structured pulses whose defined wavefront position provides robust markers for electron-density or refractive-index profiling in partially ionized atmospheres.

- Tools/workflows: Airborne/ground LIDAR systems with spatio-temporal shaping; inversion pipelines that fit wavefront motion to infer plasma properties.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-D propagation, turbulence, variable ionization; safety and regulatory constraints; sensitivity thresholds.

- Adaptive beam-shaping controllers for real-time wavefront steering (photonics)

- Develop feedback systems that tune α-distributions on-the-fly to position shock-like wavefronts where needed (e.g., in plasmas with evolving density profiles).

- Tools/workflows: Real-time SLM/AOM control, fast diagnostics, optimization algorithms; machine learning for robust control under uncertainties.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Fast, high-fidelity measurement–actuation loops; robustness to plasma nonlinearities and spatio-temporal distortions.

- Plasma-assisted materials processing and breakdown control (manufacturing)

- Use structured EM wavefronts to initiate or control plasma breakdown in solids or dielectrics with precision (e.g., laser machining, microplasma generation).

- Tools/workflows: Ultrafast laser systems with space–time shaping, process monitoring, parameter optimization to control front propagation and energy deposition.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Solid-state plasma dynamics, material response, multi-D and nonlinear effects, thermal management.

- Fusion plasma heating and current drive optimization (fusion devices)

- Investigate tailored wavepacket deposition in magnetized plasmas (ECRH, LH waves), adapting light-cone–inspired designs to improve localization and efficiency of energy transfer.

- Tools/workflows: Full-wave solvers in tokamak/stellarator geometries, spatio-temporal generator design, experimental campaigns.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Extension to magnetized, collisional, inhomogeneous plasmas; frequency-domain constraints; device integration.

Notes on assumptions and dependencies common across applications:

- The paper’s solutions assume a cold, uniform-density, single-species relativistic plasma with no collisions or magnetic fields; real systems will require generalization to multi-species, inhomogeneous, magnetized, and nonlinear regimes.

- The solutions are 1D; practical systems are multi-D. The suggested 3D extension via radial Bessel factors (J0) is a starting point but requires further development.

- Realization of light-cone dependence (functions of x±t) demands precise spatio-temporal waveform control (space–time couplings), which is feasible but nontrivial; device bandwidth, phase stability, and calibration are critical.

- Superluminal wavefront velocities do not imply superluminal energy transport; the paper shows energy velocity is always subluminal and can approach c. Applications must account for causality and energy transport constraints.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.